Marley (film)

| Marley | |

|---|---|

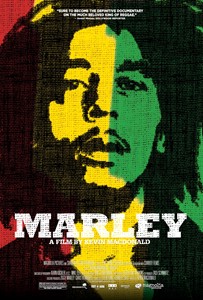

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Kevin Macdonald |

| Produced by | Charles Steele |

| Starring | Bob Marley |

| Cinematography | Mike Eley Alwin H. Küchler |

| Edited by | Dan Glendenning |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Magnolia Pictures (United States) Universal Pictures (United Kingdom) |

Release dates | |

Running time | 145 minutes[3] |

| Countries | United States United Kingdom Jamaica |

| Languages | English Jamaican Patois French |

| Box office | $1,412,124[3] |

Marley is a 2012 documentary-biographical film directed by Kevin Macdonald documenting the life of Bob Marley.[4]

The film initially began development in 2008, with a planned release date for Marley's 65th birthday on 6 February 2010. Martin Scorsese and Jonathan Demme were attached at different points but both would depart from the documentary, with Demme citing creative differences.[5] The documentary was then put on hold until Macdonald signed on as director.[6][7]

It was released on 20 April 2012, and received critical acclaim.[1][2][8] The film was also released on demand on the same day, a "day and date" release.[9] The film features archival footage and interviews.

Summary

[edit]This article's plot summary may be too long or excessively detailed. (February 2024) |

The content spans the life and musical career of Bob Marley, mainly as seen through the eyes of those who knew him and contributed to the documentary, including Bunny Wailer, Rita Marley, Lee "Scratch" Perry and many others.

Although Marley was enthusiastic about music from a very young age, he had disappointing record sales as a solo artist with his first singles, “Judge Not” and “One Cup of Coffee”. He then decided to collaborate with Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer to create “The Wailers.” This group later became known as “Bob Marley and the Wailers” and achieved international fame. The group made Bob Marley a household name and brought worldwide attention to Jamaican culture, Reggae music and the Rastafari movement.

Throughout the documentary, much of the content deals with Marley's struggle with racial identity and acceptance. Marley's widow, Rita Marley stated “they saw Bob as an outcast, because he didn’t really belong to anyone. You’re in-between. You’re black and white; so you’re not even black.” Livingston also comments that Marley was harassed in school for being mixed race. On his race, Marley stated:

"I don't have prejudice against meself. My father was a white and my mother was black. Them call me half-caste or whatever. Me don't dip on nobody's side. Me don't dip on the black man's side nor the white man's side. Me dip on God's side, the one who create me and cause me to come from black and white."

Marley's journey to become a member of the Rastafari movement is documented in the film starting with his friendship with Rastafari preacher Mortimer Planno. Marley firmly states several times that he is a key part of the Rastafari movement: the belief that the Emperor of Ethiopia, Haile Selassie I, is the reincarnation of Christ. Rita Marley stated that she also converted to Rastafari upon the visit of Selassie I to Jamaica when she saw “marks in his hands”, similar to those Jesus bore when he was nailed to the cross.

Marley's love of Rastafari was brought out in lyrics of songs such as, “Exodus” and “Jah Live”. Marley's inspiration for other songs is addressed in the documentary. Examples of this are “Corner Stone”, which dealt with the rejection of Marley by white relatives on his father's side; “Work”, which dealt with Jamaica's political conflicts; and “Zimbabwe”, which dealt with the Zimbabwean liberation movement.

Throughout Marley's life, he had a total of eleven children with seven women, despite being married from a young age. When asked if he was married, Marley responded:

"No. You see, I can’t deal with the Western ways of life. If I must live by a law, it must be the laws of His Majesty. If it’s not the laws of His Majesty, then I can make my own law."

Marley's most famous relationship was with Cindy Breakspeare (Miss World 1976). From this relationship, Breakspheare had Marley's son, Damian Marley. When asked about how she felt about Marley's relationships with other women, Rita Marley responded:

"I became his guardian angel. By that time, I was past the service of being a wife because of the importance of who I knew Bob is. I didn’t see it as a fun trip. We were on a mission. It was like an evangelist campaign to bring people closer to Jah."

Marley's death is uniquely depicted in the documentary. In 1977, Marley found out that he had a cancerous sore on his right big toe. It is believed that the sore on his toe was the result of a cancer that was already spreading in Marley's body. Contrary to those sources, Rita Marley is quoted in saying:

"Somebody stepped on it with their spiked boots and it started to get infested. But Bob would still play football the next day on it, and the next day."

The documentary also conducts interviews with Rastafari doctors, which shows Marley's strict adherence to the religion. Rastafari doctor, Carleton Fraser, states that “doctors recommended amputation of the hip and removing the entire leg.” Chris Blackwell gives conflicting information and insists that they just needed to amputate Marley's big toe for him to survive. Later, when Marley started losing his hair in the course of chemotherapy treatment for his cancer, family members also state that Marley had much displeasure in cutting off his dreadlocks, an aspect of Rastafarism, which was unfortunately necessitated by the physical pain their heavy weight was causing him.

The film ends with Marley saying a quote that was the overall message in his music:

"I don’t really have any ambition, you know? I only have one thing I’d really like to see happen. I’d like to see mankind living together. Black, White, Chinese, everyone. That’s all."

During the credits, it shows people from many countries singing the performing “Get Up, Stand Up” and “One Love”.

Interviews conducted and featured include: Cedella Marley Booker, Rita Marley, Bunny Livingston, Ziggy Marley, Cindy Breakspeare, Aston Barrett, Constance Marley (half-sister), Peter Marley (second cousin), Chris Blackwell, Peter Tosh, Lee Jaffe, Donald Kinsey, Edward Seaga, Judy Mowatt and Junior Marvin.

Music

[edit]The soundtrack to Marley was released four days prior to the film, on 16 April 2012.[10] It contains 24 of the 66 tracks listed in the closing credits of the movie. The soundtrack's first single is "High Tide or Low Tide" which was released as a single on August 9, 2011.[11] The soundtrack's track list is arranged chronologically as it appears on the film.[12] It's the first record to feature the recording of Bob Marley performing "Jamming" at the One Love Peace Concert, where Marley joined the hands of Michael Manley and Edward Seaga, members of the People's National Party and the Jamaican Labour Party respectively.[12]

The tracks listed in the film's closing credits, in order, are:

- Exodus

- Touch Me Tomato : The Jolly Boys

- Back To Back (Belly To Belly) : The Jolly Boys

- Mother & Wife : The Jolly Boys

- Depression : Bedasse with Chin's Calypso Sextet

- Rough Rider : Bedasse with The Local Calypso Quintet

- High Tide Or Low Tide

- Trench Town Rock

- Natty Dread

- Soul Rebel

- Judge Not

- This Train

- Duppy Conqueror

- Forward March : Derrick Morgan

- Simmer Down

- Kaya

- A Teenager In Love : Dion & The Belmonts

- Teenager In Love : The Wailers

- Put It On

- Mellow Mood

- Don't Rock My Boat

- Kaya (Acapella Demo)

- One Love

- "Crying in the Chapel"

- Selassie Is The Chapel

- Gotta Hold On To This Feeling

- Hold On To This Feeling

- Run For Cover

- It's Alright

- Bend Down Low

- Small Axe

- Duppy Conqueror (Live TV Studio Performance)

- Stir It Up

- Corner Stone (Jah Is Mighty alternate)

- No Woman, No Cry (Gospel Demo)

- Get Up Stand Up (Live in London, 1973)

- Concrete Jungle

- Concrete Jungle (Live TV Studio Performance)

- Stop That Train

- Roots Rock Reggae

- Rebel Music (3 O'Clock Road Block)

- No Woman, No Cry (Live At The Lyceum, London 1975)

- Crazy Baldhead

- Jamming

- Kinky Reggae

- No Sympathy

- Burnin' and Lootin'

- I Shot The Sheriff

- The Heathen

- Smile Jamaica

- Three Little Birds

- Is This Love

- War

- Work

- Crisis Dub

- Jamming (Live at One Love Peace Concert, Kingston 1978)

- No More Trouble

- Lively Up Yourself

- Real Situation

- Zimbabwe

- Could You Be Loved

- Could You Be Loved (Live at Madison Square Garden 1980)

- Is This Love (Live at Stanley Theatre, Pittsburgh 1980)

- Redemption Song

- Get Up Stand Up (Live)

- One Love/People Get Ready

Release

[edit]Box office

[edit]As of 4 August 2012, the film has grossed $1,412,124 in North America.[3]

Critical reception

[edit]At Rotten Tomatoes, Marley holds a rating of 95%, based on 93 reviews and an average rating of 7.9/10, with the critical consensus saying, "Kevin Macdonald's exhaustive, evenhanded portrait of Bob Marley offers electrifying concert footage and fascinating insights into reggae's greatest star."[13] It also has a score of 82 out of 100 on Metacritic, based on 32 reviews.[14] However the film did receive criticism, with Bunny Wailer saying that the Rastafari part of Marley's life was underplayed. Furthermore, its opening in Jamaica was soured after the colours of the Ethiopian flag were placed on the ground, causing Wailer and others to boycott the opening.[15]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Anderson, John (6 April 2012). "Hitting the Right Rhythm to Tell Marley's Story". The New York Times.

- ^ a b Adams, Tim (7 April 2012). "Bob Marley: the regret that haunted his life". The Guardian.

- ^ a b c "Marley (2012)". Box Office Mojo. Amazon.com. Retrieved 5 June 2012.

- ^ Fernandez, Jay A. (12 March 2012). "SXSW 2012: Kevin Macdonald Talks 'Marley,' Music and Marijuana". The Hollywood Reporter.

- ^ "Demme takes over Bob Marley film". Variety. 21 May 2008. Archived from the original on 29 May 2008. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Perez, Rodrigo (5 October 2009). "Exclusive: Jonathan Demme Says Bob Marley Documentary On Hold, But Not Necessarily Over For Him". The Playlist. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (2 February 2011). "Kevin Macdonald Jamming On Bob Marley Docu". Deadline. Archived from the original on 2 November 2014. Retrieved 18 March 2022.

- ^ "Jamaica premiere for Marley tribute". www.independent.ie. 20 April 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- ^ "Director Kevin Macdonald Discusses 'Marley' Documentary - Speakeasy - WSJ". Blogs.wsj.com. 13 April 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2017.

- ^ "Marley (Original Soundtrack) – United States". iTunes. Apple, Inc. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ "High Tide or Low Tide - Single – United States". iTunes. Apple, Inc. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ^ a b "Marley Soundtrack - bobmarley.com". Island Records. Tuff Gong Records. Retrieved 22 April 2012.

- ^ "Marley (2012)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved 3 May 2012.

- ^ "Marley". Metacritic. Retrieved 23 April 2012.

- ^ "Wailer unhappy with MARLEY FILM". Jamaicaobserver.com. 29 April 2012. Retrieved 20 July 2017.