Marginal product of capital

In economics, the marginal product of capital (MPK) is the additional production that a firm experiences when it adds an extra unit of input.[1] It is a feature of the production function, alongside the labour input.

Definition

[edit]The marginal product of capital (MPK) is the additional output resulting, ceteris paribus ("all things being equal"), from the use of an additional unit of physical capital, such as machines or buildings used by businesses.

The marginal product of capital (MPK) is the amount of extra output the firm gets from an extra unit of capital, holding the amount of labor constant:

Thus, the marginal product of capital is the difference between the amount of output produced with K + 1 units of capital and that produced with only K units of capital.[2]

Determining marginal product of capital is essential when a firm is debating on whether or not to invest on the additional unit of capital. The decision of increasing the production is only beneficial if the MPK is higher than the cost of capital of each additional unit. Otherwise, if the cost of capital is higher, the firm will be losing profit when adding extra units of physical capital.[3] This concept equals the reciprocal of the incremental capital-output ratio. Mathematically, it is the partial derivative of the production function with respect to capital. If production output , then

Diminishing marginal returns

[edit]One of the key assumptions in economics is diminishing returns, that is the marginal product of capital is positive but decreasing in the level of capital stock, or mathematically

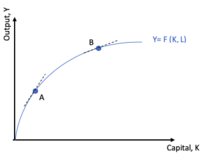

Graphically, this evidence can be observed by the curve shown on the graphic, which represents the effect of capital, K, on the output, Y. If the quantity of labor input, L, is hold fixed, the slope of the curve at any point resemble the marginal product of capital. In a low quantity of capital, such as point A, the slope is steeper than in point B, due to diminishing returns of capital. By other words, the additional unit of capital has diminishing productivity, once the increase on production becomes less and less significant, as K rises.[4]

Example

[edit]Consider a furniture firm, in which labour input, that is, the number of employees is given as fixed, and capital input is translated in the number of machines of one of its factories. If the firm has no machines, it would produce zero furnitures. If there is one machine in the factory, sixteen furnitures would be produced. When there are two machines, twenty eight furnitures are built. However, as the number of machines available increase, the change in the output turns out to be less significant compared to the previous number. That fact can be observed in the marginal product which begins to decrease: diminishing marginal returns. This is justified by the fact that there is not enough employees to work with the extra machines, so the value that these additional units bring to the company, in terms of output generated, starts to decrease.

| Number of machines | Output (Furnitures produced per day) | Marginal Product of Capital |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1 | 16 | 16 |

| 2 | 28 | 12 |

| 3 | 39 | 11 |

| 4 | 46 | 7 |

| 5 | 49 | 3 |

| 6 | 50 | 1 |

Rental rate of capital

[edit]In a perfectly competitive market, a firm will continue to add capital until the point where MPK is equal to the rental rate of capital, which is called equilibrium point. This fact justifies why in perfectly competitive capital markets, the price of capital can be seen as the rental rate.[5] The price of capital is determined in the capital market by the respective capital demand and supply.

The marginal product of capital determines the real rental price of capital. The real interest rate, the depreciation rate, and the relative price of capital goods determine the cost of capital. According to the neoclassical model, firms invest if the rental price is greater than the cost of capital, and they disinvest if the rental price is less than the cost of capital.[2]

MRPK, MCK and profit maximization

[edit]It is only profitable for a firm to keep adding capital when the marginal revenue product of capital, MRPK (the change in total revenue, when there is a unit change of capital input, ∆TR/∆K) is higher than the marginal cost of capital, MCK (marginal cost of obtaining and utilizing a machine, for example). Thus, the profit of the firm will reach its maximum point when MRPK = MCK.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "What is Marginal Product of Capital?". My Accounting Course.

- ^ a b N. Gregory Mankiw. (2010). Macroeconomics. United States: Worth Publishers

- ^ "Marginal product of Capital". XPLAIND. Obaidullah Jan. 24 January 2019.

- ^ Intermediate Macroeconomics (First ed.). Robert J. Barro. 2017. ISBN 9781473725096.

- ^ "Rental rate". Boundless.

Sources

[edit]- Nicholson, Walter (1978). Microeconomic Theory: Basic Principles and Extensions (2nd ed.). Hinsdale: Dryden Press. pp. 182–188. ISBN 0-03-020831-9.

- Robinson, R. Clark. "Marginal product of labor and capital" (PDF). Northwestern University Class Handout. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 9, 2006.