Marc Bloch

Marc Bloch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 6 July 1886 |

| Died | 16 June 1944 (aged 57) |

| Cause of death | Summary execution |

| Resting place | Le Bourg-d'Hem |

| Education | Lycée Louis-le-Grand |

| Alma mater | École Normale Supérieure |

| Occupation | Historian |

| Spouse | Simonne Vidal |

| Children | Alice and Étienne |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | French Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1918, 1939 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Awards | Legion of Honor War Cross (1914–1918) War Cross (1939–1945) |

Marc Léopold Benjamin Bloch (/blɒk/; French: [maʁk leɔpɔld bɛ̃ʒamɛ̃ blɔk]; 6 July 1886 – 16 June 1944) was a French historian. He was a founding member of the Annales School of French social history. Bloch specialised in medieval history and published widely on Medieval France over the course of his career. As an academic, he worked at the University of Strasbourg (1920 to 1936 and 1940 to 1941), the University of Paris (1936 to 1939), and the University of Montpellier (1941 to 1944).

Born in Lyon to an Alsatian Jewish family, Bloch was raised in Paris, where his father—the classical historian Gustave Bloch—worked at Sorbonne University. Bloch was educated at various Parisian lycées and the École Normale Supérieure, and from an early age was affected by the antisemitism of the Dreyfus affair. During the First World War, he served in the French Army and fought at the First Battle of the Marne and the Somme. After the war, he was awarded his doctorate in 1918 and became a lecturer at the University of Strasbourg. There, he formed an intellectual partnership with modern historian Lucien Febvre. Together they founded the Annales School and began publishing the journal Annales d'histoire économique et sociale in 1929. Bloch was a modernist in his historiographical approach, and repeatedly emphasised the importance of a multidisciplinary engagement towards history, particularly blending his research with that on geography, sociology and economics, which was his subject when he was offered a post at the University of Paris in 1936.

During the Second World War Bloch volunteered for service, and was a logistician during the Phoney War. Involved in the Battle of Dunkirk and spending a brief time in Britain, he unsuccessfully attempted to secure passage to the United States. Back in France, where his ability to work was curtailed by new antisemitic regulations, he applied for and received one of the few permits available allowing Jews to continue working in the French university system. He had to leave Paris, and complained that the Nazi German authorities looted his apartment and stole his books; he was also persuaded by Febvre to relinquish his position on the editorial board of Annales. Bloch worked in Montpellier until November 1942 when Germany invaded Vichy France. He then joined the non-Communist section of the French Resistance and went on to play a leading role in its unified regional structures in Lyon. In 1944, he was captured by the Gestapo in Lyon and murdered in a summary execution after the Allied invasion of Normandy. Several works—including influential studies like The Historian's Craft and Strange Defeat—were published posthumously.

His historical studies and his death as a member of the Resistance together made Bloch highly regarded by generations of post-war French historians; he came to be called "the greatest historian of all time".[1] By the end of the 20th century, historians were making a more critical assessment of Bloch's abilities, influence, and legacy, arguing that there were flaws to his approach.

Youth and upbringing

[edit]Family

[edit]Marc Bloch was born in Lyon on 6 July 1886,[2] one of two children[3] to Gustave[note 1] and Sarah Bloch,[3] née Ebstein.[5] Bloch's family were Alsatian Jews: secular, liberal and loyal to the French Republic.[6] They "struck a balance", says the historian Carole Fink, between both "fierce Jacobin patriotism and the antinationalism of the left".[7] His family had lived in Alsace for five generations under French rule. In 1871, France was forced to cede the region to Germany following its defeat in the Franco-Prussian War.[8][note 2] The year after Bloch's birth, his father was appointed professor of Roman History at the Sorbonne, and the family moved to Paris[10]—"the glittering capital of the Third Republic".[11] Marc had a brother, Louis Constant Alexandre,[5] seven years his senior. The two were close, although Bloch later described Louis as being occasionally somewhat intimidating.[3] The Bloch family lived at 72, Rue d'Alésia, in the 14th arrondissement of Paris. Gustave began teaching Marc history while he was still a boy,[3] with a secular, rather than Jewish, education intended to prepare him for a career in professional French society.[12] Bloch's later close collaborator, Lucien Febvre, visited the Bloch family at home in 1902;[3] although the reason for Febvre's visit is now unknown, he later wrote of Bloch that "from this fleeting meeting, I have kept the memory of a slender adolescent with eyes brilliant with intelligence and timid cheeks—a little lost then in the radiance of his older brother, future doctor of great prestige".[13]

Upbringing and education

[edit]Bloch's biographer Katherine Stirling ascribed significance to the era in which Bloch was born: the middle of the French Third Republic, so "after those who had founded it and before the generation that would aggressively challenge it".[6][note 3] When Bloch was nine-years-old, the Dreyfus affair broke out in France. As the first major display of political antisemitism in Europe, it was probably a formative event of Bloch's youth,[15][note 4] along with, more generally, the atmosphere of fin de siècle Paris.[6] Bloch was 11 when Émile Zola published J'Accuse…!, his indictment of the French establishment's antisemitism and corruption.[17] Bloch was greatly affected by the Dreyfus affair, but even more affected was nineteenth-century France generally, and his father's employer, the École Normale Supérieure, saw existing divides in French society reinforced in every debate.[14] Gustave Bloch was closely involved in the Dreyfusard movement and his son agreed with the cause.[14]

Bloch was educated at the prestigious Lycée Louis-le-Grand for three years, where he was consistently head of his class and won prizes in French, history, Latin, and natural history.[3] He passed his baccalauréat, in Letters and Philosophy, in July 1903, being graded trés bien (very good).[18] The following year,[6] he received a scholarship[18] and undertook postgraduate study there for the École normale supérieure (ÉNS)[6] (where his father had been appointed maître de conferences in 1887).[19] His father had been nicknamed le Méga by his students at the ÉNS and the moniker Microméga was bestowed upon Bloch.[20][note 5] Here he was taught history by Christian Pfister[21] and Charles Seignobos, who led a relatively new school of historical thought which saw history as broad themes punctuated by tumultuous events.[6] Another important influence on Bloch from this period was his father's contemporary, the sociologist Émile Durkheim, who pre-figured Bloch's own later emphasis on cross-disciplinary research.[6] The same year, Bloch visited England; he later recalled being struck more by the number of homeless people on the Victoria Embankment than the new Entente Cordiale relationship between the two countries.[22]

The Dreyfus affair had soured Bloch's views of the French Army, and he considered it laden with "snobbery, anti-semitism and anti-republicanism".[23] National service had been made compulsory for all French adult males in 1905, with an enlistment term of two years.[24] Bloch joined the 46th Infantry Regiment based at Pithiviers from 1905 to 1906.[23]

Early research

[edit]

By this time, changes were taking place in French academia. In Bloch's own speciality of history, attempts were being made at instilling a more scientific methodology. In other, newer departments such a sociology, efforts were made at establishing an independent identity.[25] Bloch graduated in 1908 with degrees in both geography and history (Davies notes, given Bloch's later divergent interests, the significance of the two qualifications).[4] He had a high respect for historical geography, then a speciality of French historiography,[26] as practised by his tutor Vidal de la Blache whose Tableau de la géographie Bloch had studied at the ÉNS,[27] and Lucien Gallois.[26] Bloch applied unsuccessfully for a fellowship at the Fondation Thiers.[28] As a result,[28] he travelled to Germany in 1909[4] where he studied demography under Karl Bücher in Leipzig and religion[21] under Adolf Harnack in Berlin;[4] he did not, however, particularly socialise with fellow students while in Germany.[20] He returned to France the following year and again applied to the Fondation, this time successfully.[28] Bloch researched the medieval Île-de-France[4] in preparation for his thesis.[10] This research was Bloch's first focus on rural history.[29] His parents had moved house and now resided at the Avenue d'Orleans, not far from Bloch's quarters.[30][note 6]

Bloch's research at the Fondation[note 7]—especially his research into the Capetian kings—laid the groundwork for his career.[33] He began by creating maps of the Paris area illustrating where serfdom had thrived and where it had not. He also investigated the nature of serfdom, the culture of which, he discovered, was founded almost completely on custom and practice.[30] His studies of this period formed Bloch into a mature scholar and first brought him into contact with other disciplines whose relevance he was to emphasise for most of his career. Serfdom as a topic was so broad that he touched on commerce, currency, popular religion, the nobility, as well as art, architecture, and literature.[30] His doctoral thesis—a study of 10th-century French serfdom—was titled Rois et Serfs, un Chapitre d'Histoire Capétienne. Although it helped mould Bloch's ideas for the future, it did not, says Bryce Loyn, give any indication of the originality of thought that Bloch would later be known for,[21] and was not vastly different to what others had written on the subject.[2] Following his graduation, he taught at two lycées,[21] first in Montpelier, a minor university town of 66,000 inhabitants.[34] With Bloch working over 16 hours a week on his classes, there was little time for him to work on his thesis.[34] He also taught at the University of Amiens.[4] While there, he wrote a review of Febvre's first book, Histoire de Franche-Comté.[35] Bloch intended to turn his thesis into a book, but the First World War intervened.[36][note 8]

First World War

[edit]Both Marc and Louis Bloch volunteered for service in the French Army.[37] Although the Dreyfus Affair had soured Bloch's views of the French Army, he later wrote that his criticisms were only of the officers; he "had respect only for the men".[38] Bloch was one of over 800 ÉNS students who enlisted; 239 were to be killed in action.[39] On 2 August 1914[31] he was assigned to the 272nd Reserve Regiment.[35] Within eight days he was stationed on the Belgian border where he fought in the Battle of the Meuse later that month. His regiment took part in the general retreat on the 25th, and the following day they were in Barricourt, in the Argonne. The march westward continued towards the river Marne—with a temporary recuperative halt in Termes—which they reached in early September. During the First Battle of the Marne, Bloch's troop was responsible for the assault and capture of Florent before advancing on La Gruerie.[40] Bloch led his troop with shouts of "Forward the 18th!" They suffered heavy casualties: 89 men were either missing or known to be dead.[40] Bloch enjoyed the early days of the war;[31] like most of his generation, he had expected a short but glorious conflict.[31] Gustave Bloch remained in France, wishing to be close to his sons at the front.[37]

Except for two months in hospital followed by another three recuperating, he spent the war in the infantry;[31] he joined as a sergeant and rose to become the head of his section.[41] Bloch kept a war diary from his enlistment. Very detailed in the first few months, it rapidly became more general in its observations. However, says the historian Daniel Hochedez, Bloch was aware of his role as both a "witness and narrator" to events and wanted as detailed a basis for his historiographical understanding as possible.[41] The historian Rees Davies notes that although Bloch served in the war with "considerable distinction",[4] it had come at the worst possible time both for his intellectual development and his study of medieval society.[4]

For the first time in his life, Bloch later wrote, he worked and lived alongside people he had never had close contact with before, such as shop workers and labourers,[21] with whom he developed a great camaraderie.[42] It was a completely different world to the one he was used to, being "a world where differences were settled not by words but by bullets".[21] His experiences made him rethink his views on history,[43] and influenced his subsequent approach to the world in general.[44] He was particularly moved by the collective psychology he witnessed in the trenches.[45] He later declared he knew of no better men than "the men of the Nord and the Pas de Calais"[10] with whom he had spent four years in close quarters.[10][note 9] His few references to the French generals were sparse and sardonic.[46]

Apart from the Marne, Bloch fought at the battles of the Somme, the Argonne, and the final German assault on Paris. He survived the war,[47] which he later described as having been an "honour" to have served through.[41] He had, however, lost many friends and colleagues.[48] Among the closest of them, all killed in action, were: Maxime David (died 1914), Antoine-Jules Bianconi (died 1915) and Ernest babut (died 1916).[39] Bloch himself was wounded twice[35] and decorated for courage,[42] receiving the Croix de Guerre[49] and the Légion d'Honneur.[41] He had joined as a non-commissioned officer, received an officer's commission after the Marne,[50] and had been promoted to warrant officer[51] and finally a captain in the fuel service, (Service des essences) before the war ended.[20] He was clearly, says Loyn, both a good and a brave soldier;[52] he later wrote, "I know only one way to persuade a troop to brave danger: brave it yourself".[53]

While on front-line service, Bloch contracted severe arthritis which required him to retire regularly to the thermal baths of Aix-les-Bains for treatment.[47] He later remembered very little of the historical events he found himself in, writing only that his memories were[54][45] "a discontinuous series of images, vivid in themselves, but badly arranged, like a reel of motion picture film containing some large gaps and some reversals of certain scenes".[54] Bloch later described the war, in a detached style, as having been a "gigantic social experience, of unbelievable richness".[55] For example, he had a habit of noting the different coloured smoke that different shells made — percussion bombs had black smoke, timed bombs were brown.[31] He also remembered both the "friends killed at our side ... of the intoxication which had taken hold of us when we saw the enemy in flight".[10] He also considered it to have been "four years of fighting idleness".[31] Following the Armistice in November 1918, Bloch was demobilised on 13 March 1919.[31][56]

Career

[edit]Early career

[edit]"Must I say historical or indeed sociological? Let us more simply say, in order to avoid any discussion of method, human studies. Durkheim was no longer there, but the team he had grouped around him survived him...and the spirit which animates it remains the same".[57]

Marc Bloch, review of L'Année Sociologique, 1923–1925

The war was fundamental in re-arranging Bloch's approach to history, although he never acknowledged it as a turning point.[2] In the years following the war, a disillusioned Bloch rejected the ideas and the traditions that had formed his scholarly training. He rejected the political and biographical history which up until that point was the norm,[58] along with what the historian George Huppert has described as a "laborious cult of facts" that accompanied it.[59] In 1920, with the opening of the University of Strasbourg,[60] Bloch was appointed chargé de cours[56] (assistant lecturer)[61] of medieval history.[4] Alsace-Lorraine had been returned to France with the Treaty of Versailles; the status of the region was a contentious political issue in Strasbourg, its capital, which had a large German population.[60] Bloch, however, refused to take either side in the debate; indeed, he appears to have avoided politics entirely.[56] Under Wilhelmine Germany, Strasbourg had rivalled Berlin as a centre for intellectual advancement, and the University of Strasbourg possessed the largest academic library in the world. Thus, says Stephan R. Epstein of the London School of Economics, "Bloch's unrivalled knowledge of the European Middle Ages was ... built on and around the French University of Strasbourg's inherited German treasures".[62][note 10] Bloch also taught French to the few German students who were still at the Centre d'Études Germaniques at the University of Mainz during the Occupation of the Rhineland.[56] He refrained from taking a public position when France occupied the Ruhr in 1923 over Germany's perceived failure to pay war reparations.[64]

Bloch began working energetically,[60] and later said that the most productive years of his life were spent at Strasbourg.[56] In his teaching, his delivery was halting. His approach sometimes appeared cold and distant—caustic enough to be upsetting[56]—but conversely, he could be also both charismatic and forceful.[60] Durkheim died in 1917, but the movement he began against the "smugness" that pervaded French intellectual thinking continued.[65] Bloch had been greatly influenced by him, as Durkheim also considered the connections between historians and sociologists to be greater than their differences. Not only did he openly acknowledge Durkheim's influence, but Bloch "repeatedly seized any opportunity to reiterate" it, according to R. C. Rhodes.[66]

At Strasbourg, he again met Febvre, who was now a leading historian[56] of the 16th century.[67] Modern and medieval seminars were adjacent to each other at Strasbourg, and attendance often overlapped.[56] Their meeting has been called a "germinal event for 20th-century historiography",[68] and they were to work closely together for the rest of Bloch's life. Febvre was some years older than Bloch and was probably a great influence on him.[69] They lived in the same area of Strasbourg[56] and became kindred spirits,[70] often going on walking trips across the Vosges and other excursions.[29]

Bloch's fundamental views on the nature and purpose of the study of history were established by 1920.[71] That same year he defended,[19] and subsequently published, his thesis.[4] It was not as extensive a work as had been intended due to the war.[72] There was a provision in French further education for doctoral candidates for whom the war had interrupted their research to submit only a small portion of the full-length thesis usually required.[29] It sufficed, however, to demonstrate his credentials as a medievalist in the eyes of his contemporaries.[29] He began publishing articles in Henri Berr's Revue de Synthèse Historique.[73] Bloch also published his first major work, Les Rois thaumaturges, which he later described as "ce gros enfant" (this big child).[74] In 1928, Bloch was invited to lecture at the Institute for the Comparative Study of Civilizations in Oslo. Here he first expounded publicly his theories on total, comparative history:[43][note 11] "it was a compelling plea for breaking out of national barriers that circumscribed historical research, for jumping out of geographical frameworks, for escaping from a world of artificiality, for making both horizontal and vertical comparisons of societies, and for enlisting the assistance of other disciplines".[43]

Comparative history and the Annales

[edit]

His 1928 Oslo lecture, called "Towards a Comparative History of Europe",[20] formed the basis of his next book, Les Caractères Originaux de l'Histoire Rurale Française.[76] In the same year[77] he founded the historical journal Annales with Febvre.[4] One of its aims was to counteract the administrative school of history, which Davies says had "committed the arch error of emptying history of human element". As Bloch saw it, it was his duty to correct that tendency.[78] Both Bloch and Febvre were keen to refocus French historical scholarship on social rather than political history and to promote the use of sociological techniques.[77] The journal avoided narrative history almost completely.[67]

The inaugural issue of the Annales stated the editors' basic aims: to counteract the arbitrary and artificial division of history into periods, to re-unite history and social science as a single body of thought, and to promote the acceptance of all other schools of thought into historiography. As a result, the Annales often contained commentary on contemporary, rather than exclusively historical, events.[77] Editing the journal led to Bloch forming close professional relationships with scholars in different fields across Europe.[79] The Annales was the only academic journal to boast a preconceived methodological perspective. Neither Bloch nor Febvre wanted to present a neutral facade. During the decade it was published it maintained a staunchly left-wing position.[80] Henri Pirenne, a Belgian historian who wrote comparative history, closely supported the new journal.[81] Before the war he had acted in an unofficial capacity as a conduit between French and German schools of historiography.[82] Fernand Braudel—who was himself to become an important member of the Annales School after the Second World War—later described the journal's management as being a chief executive officer—Bloch—with a minister of foreign affairs—Febvre.[83]

Utilizing comparative methodology allowed Bloch to discover instances of uniqueness within aspects of society,[84] and he advocated it as a new kind of history.[70] According to Bryce Lyon, Braudel and Febvre, "promising to perform all the burdensome tasks" themselves, asked Pirenne to become editor-in-chief of Annales to no avail. Pirenne remained a strong supporter, however, and had an article published in the first volume in 1929.[70] He became close friends with both Bloch and Febvre. He was particularly influential on Bloch, who later said that Pirenne's approach should be the model for historians and that "at the time his country was fighting beside mine for justice and civilisation, wrote in captivity a history of Europe".[81] The three men kept up a regular correspondence until Pirenne's death in 1935.[70] In 1923, Bloch attended the inaugural meeting of the International Congress on Historical Studies (ICHS) in Brussels, which was opened by Pirenne. Bloch was a prolific reviewer for Annales, and during the 1920s and 1930s he contributed over 700 reviews. These included criticisms of specific works, but more generally, represented his own fluid thinking during this period. The reviews demonstrate the extent to which he shifted his thinking on particular subjects.[85]

Move to Paris

[edit]In 1930, both keen to make a move to Paris, Febvre and Bloch applied to the École pratique des hautes études for a position: both failed.[86] Three years later Febvre was elected to the Collège de France. He moved to Paris, and in doing so, says Fink, became all the more aloof.[87] This placed a strain on Bloch's and his relations,[87] although they communicated regularly by letter and much of their correspondence is preserved.[88] In 1934, Bloch was invited to speak at the London School of Economics. There he met Eileen Power, R. H. Tawney and Michael Postan, among others. While in London, he was asked to write a section of the Cambridge Economic History of Europe; at the same time, he also attempted to foster interest in the Annales among British historians.[76][note 12] He later told Febvre in some ways he felt he had a closer affinity with academic life in England than that of France.[90] For example, in comparing the Bibliothèque Nationale with the British Museum, he said that[91]

A few hours work in the British [Museum] inspire the irresistible desire to build in the Square Louvois a vast pyre of all the B.N.'s regulations and to burn on it, in splendid auto-de-fé, Julian Cain [the director], his librarians and his staff...[and] also a few malodorous readers, if you like, and no doubt also the architect ... after which we could work and invite the foreigners to come and work".[91]

Isolated, each [historian] will understand only by halves, even within his own field of study, for the only true history, which can advance only through mutual aid, is universal history'.[92]

Marc Bloch, The Historian's Craft

During this period he supported the Popular Front politically.[93] Although he did not believe it would do any good, he signed Alain's—Émile Chartier's pseudonym—petition against Paul Boncour's Militarisation laws in 1935.[64][94] While he was opposed to the rise of European fascism, he also objected to attempting to counter the ideology through "demagogic appeals to the masses," as the Communist Party was doing.[64] Febvre and Bloch were both firmly on the left, although with different emphases. Febvre, for example, was more militantly Marxist than Bloch, while the latter criticised both the pacifist left and corporate trade unionism.[95]

In 1934, Étienne Gilson sponsored Bloch's candidacy for a chair at the Collège de France.[96] The college, says the historian Eugen Weber, was Bloch's "dream" appointment—although one never to be realised—as it was one of the few (possibly the only) institutions in France where personal research was central to lecturing.[97] Camille Jullian had died the previous year, and his position was now available. While he had lived, Julian had wished for his chair to go to one of his students, Albert Grenier, and after his death, his colleagues generally agreed with him.[97] However, Gilson proposed that not only should Bloch be appointed, but that the position be redesignated the study of comparative history. Bloch, says Weber, enjoyed and welcomed new schools of thought and ideas, but mistakenly believed the college should do so also; the college did not. The contest between Bloch and Grenier was not just the struggle for one post between two historians; it was also a struggle to determine which path historiography within the college would take for the next generation.[98] To complicate the situation further, the country was in both political and economic crises, and the college's budget was slashed by 10%. No matter who filled it, this made another new chair financially unviable. By the end of the year, and with further retirements, the college had lost four professors: it could replace only one, and Bloch was not appointed.[99] Bloch personally suspected his failure was due to antisemitism and Jewish quotas. At the time, Febvre blamed it on a distrust of Bloch's approach to scholarship by the academic establishment, although Epstein has argued that this could not have been an over-riding fear as Bloch's next appointment indicated.[76]

Joins the Sorbonne

[edit]We sometimes clashed...so close to each other and yet so different. We threw our 'bad character' in each other's faces, after which we found ourselves more united than ever in our common hatred of bad history, of bad historians—and of bad Frenchmen who were also bad Europeans.[88]

Lucien Febvre

Henri Hauser retired from the Sorbonne in 1936, and his chair in economic history[50] was up for appointment.[100] Bloch—"distancing himself from the encroaching threat of Nazi Germany"[101]—applied and was approved for his position.[4] This was a more demanding position than the one he had applied for at the college.[67] Weber has suggested Bloch was appointed because unlike at the college, he had not come into conflict with many faculty members.[100] Weber researched the archives of the college in 1991 and discovered that Bloch had indicated an interest in working there as early as 1928, even though that would have meant him being appointed to the chair in numismatics rather than history. In a letter to the recruitment board written the same year, Bloch indicated that although he was not officially applying, he felt that "this kind of work (which he claimed to be alone in doing) deserves to have its place one day in our great foundation of free scientific research".[97] H. Stuart Hughes says of Bloch's Sorbonne appointment: "In another country, it might have occasioned surprise that a medievalist like Bloch should have been named to such a chair with so little previous preparation. In France it was only to be expected: no one else was better qualified".[29] His first lecture was on the theme of never-ending history, a process, a never-to-be-finished thing.[102] Davies says his years at the Sorbonne were to be "the most fruitful" of Bloch's career,[4] and according to Epstein he was by now the most significant French historian of his age.[79] In 1936, Friedman says he considered using Marx in his teachings, with the intention of bringing "some fresh air" into the Sorbonne.[64]

The same year, Bloch and his family visited Venice, where they were chaperoned by the Italian historian Gino Luzzatto.[103][note 13] During this period they were living in the Sèvres – Babylone area of Paris, next to the Hôtel Lutetia.[105]

By now, Annales was being published six times a year to keep on top of current affairs, however, its "outlook was gloomy".[80] In 1938, the publishers withdrew support and, experiencing financial hardship, the journal moved to cheaper offices, raised its prices, and returned to publishing quarterly.[106] Febvre increasingly opposed the direction Bloch wanted to take the journal. Febvre wanted it to be a "journal of ideas",[77] whereas Bloch saw it as a vehicle for the exchange of information to different areas of scholarship.[77]

By early 1939, war was known to be imminent. Bloch, in spite of his age, which automatically exempted him,[95] had a reserve commission for the army[29] holding the rank of captain.[47] He had already been mobilised twice in false alarms.[47] In August 1939, he and his wife Simonne intended to travel to the ICHS in Bucharest.[47] In autumn 1939,[47] just before the outbreak of war, Bloch published the first volume of Feudal Society.[4]

Second World War

[edit]Torn from normal behaviour and from normal expectations, suspended from history and from commonsense responses, members of a huge French army became separated for an indefinite period from their work and their loved ones. Sixty-seven divisions, lacking strong leadership, public support, and solid allies, waited almost three-quarters of a year to be attacked by a ruthless, stronger force.[47]

Carole Fink

On 24 August 1939, at the age of 53,[47] Bloch was mobilised for a third time.[47] He was responsible for the mobilisation of the French Army's massive motorised units[107] which involved him undertaking such a detailed assessment of the French fuel supply that he later wrote he was able to "count petrol tins and ration every drop" of fuel he obtained.[107] During the first few months of the war, called the Phoney War,[108][note 14] he was stationed in Alsace,[109] this time lacking the eager patriotism he had shown in the war.[9] He also evacuated civilians to behind the Maginot Line[110] and for a while he worked with British Intelligence.[111][note 15]

Bloch began but did not complete writing a history of France.[112][113] At one point he expected to be invited to neutral Belgium to deliver a series of lectures in Liège, on Belgian neutrality.[113] Some academics had escaped France for The New School in New York City, and the School also invited Bloch. He refused,[114] possibly because of difficulties in obtaining visas:[115] the US government would not grant visas to every member of his family.[116]

Fall of France

[edit]

In May 1940, the German army forced the French to withdraw.[67][117][118] Bloch fought at the Battle of Dunkirk in May–June 1940, being evacuated to England.[100] Although he could have remained in Britain,[119] he chose to return to France[67] because his family was still there.[119]

[120] To Bloch, France collapsed because her generals failed to capitalise on the best qualities humanity possessed—character and intelligence[121]—because of their own "sluggish and intractable" progress since the First World War.[108]

Two-thirds of France was occupied by Germany.[122] Bloch was demobilised soon after Philippe Pétain's government signed the Armistice of 22 June 1940 forming Vichy France.[123] Bloch received[124] a permit to work despite being Jewish.[87] This was probably due to Bloch's pre-eminence in the field of history.[115] He worked again at the University of Strasbourg, now relocated to Clermont-Ferrand, for one academic year before moving to Montpellier.[125][126] In Clermont-Ferrand, his two older sons were involved with the Christian-conservative Gaullist[127] Resistance organisation Combat.[128] In November 1940 he received an offer of employment from The New School in New York, but he delayed his decision due to his reluctance to leave family members behind; it expired in July 1941 before he could obtain visas for his adult children.[129][125] Montpellier, further south, was beneficial to his wife's declining health.[29] The dean of faculty at Montpellier was an antisemite,[130] who also disliked Bloch for having once given him a poor review.[130] Bloch rejected the Vichy propaganda notion of returning to traditional French values,[131] arguing that "the idyllic, docile peasant life of the French right had never existed".[132] In Montpellier, he had to be escorted to class for protection from militant right-wing students.[133] His university contacts included the local leaders of Combat and organisers of the Comité Général d'Etudes (an underground Conseil d'État[134]), René Courtin and Pierre-Henri Teitgen.[133] He also knew the sociologist and Communist Resistance member Georges Friedmann and the philosopher of mathematics Jean Cavaillès,[133] a key Resistance figure who co-founded the left-wing Libération-sud in Clermont-Ferrand in December 1940, was arrested in Narbonne in September 1942 and escaped from Montpellier prison in December 1942.

Declining relationship with Febvre

[edit]It was during these bitter years of defeat, of personal recrimination, of insecurity that he wrote both the uncompromisingly condemnatory pages of Strange Defeat and the beautifully serene passages of The Historian's Craft.

Bloch's professional relationship with Febvre was also under strain. The Nazis wanted French editorial boards to be stripped of Jews in accordance with German racial policies. Facing the potential seizure or liquidation of Annales, Febvre insisted on continuing to publish it in Paris to ensure an international distribution and demanded that Bloch step down for the sake of preserving their project. Bloch initially refused what he called "an abdication" and proposed to move the journal to the unoccupied zone.[135][93][136] In his desire to keep the journal afloat at all costs, Febvre went so far as to point out that Bloch had himself tried to rescue his Paris library.[137] Bloch, forced to accede, turned the Annales over to the sole editorship of Febvre, who then changed the journal's name to Mélanges d'Histoire Sociale. Bloch was forced to write for it under the pseudonym Marc Fougères.[93]

The Annalist historian André Burguière suggests Febvre did not really understand the position Bloch, or any French Jew, was in.[138] Already damaged by this disagreement, Bloch's and Febvre's relationship declined further when the former had been forced to leave his library and papers[115] in his Paris apartment following his move to Vichy. On account of limited space in Montpellier, he had attempted to have them transported to his country home in Fougères.[138][139] Eventually the Nazis looted his apartment and removed the library in January 1942.[140][105] Bloch held Febvre responsible, believing he could have done more to prevent it.[87] Bloch had refused to donate the library to the University of Montpellier at the advice of the Vichy education minister, his friend Jérôme Carcopino, and later protested the loss to the newly appointed minister Abel Bonnard.[141]

Bloch's mother had recently died, and his wife was ill; he faced daily harassment.[115] On 18 March 1941, Bloch made his will in Clermont-Ferrand.[142] The Polish social historian Bronisław Geremek suggests that this document hints at Bloch in some way foreseeing his death,[143] as he emphasised that nobody had the right to avoid fighting for their country.[144]

French resistance

[edit]

In November 1942 Germany occupied the territory previously under direct Vichy rule.[115] This was the catalyst for Bloch's decision to join the moderate republican Franc-Tireur movement (FT) in the French Resistance, led by Jean-Pierre Lévy, which was being integrated by Jean Moulin into Mouvements unis de la Résistance (MUR), by March 1943.[145][127][126][101] Bloch had previously expressed the view that "there can be no salvation where there is not some sacrifice".[126] He sent his family away to Fougères (except for his daughter who worked in Limoges and for his two elder sons whom he helped cross the border to Francoist Spain[146]) and moved to Lyon to join the underground,[115] although he found this difficult because of his age.[95] Bloch used his professional and military skills for the movement, writing propaganda and organising supplies and materiel in the region.[115] He wrote for the underground FT magazines Franc-Tireur, La Revue libre and Le Père Duchesne, and by 1944 oversaw the distribution of the first title.[147] He was a member of FT's steering committee and since July 1943 represented it in the regional directory of the MUR.[147] Often on the move, Bloch used archival research as his excuse for travelling.[100] The journalist-turned-resistance fighter Georges Altman later told how he knew Bloch as, although originally "a man, made for the creative silence of gentle study, with a cabinet full of books" was now "running from street to street, deciphering secret letters in some Lyonaisse Resistance garret".[148] For the first time, suggests Lyon, Bloch was forced to consider the role of the individual in history, rather than the collective; perhaps by then even realising he should have done so earlier.[149][note 16]

Arrest, interrogation and death

[edit]Bloch was arrested by the Gestapo on the Pont de la Boucle in Lyon, shortly after leaving his nearby address on the morning of 8 March 1944,[125][151][1][152] as part of a wave of arrests launched by the new chief of French police, Joseph Darnand.[153] At the time, he was the acting head of the regional directory of the MUR for Rhône-Alpes,[154] tasked with preparing the uprising and seizure of power to coincide with the Allied landing (Jour-J),[147] and used the aliases "Maurice Blanchard" and "Narbonne".[155][1][156] The regional directory was scheduled to meet on the afternoon of that day, but on 7 March a number of key people had been arrested, including the local Combat leader Robert Blanc ('Drac') and Bloch's nephew and adjutant Jean Bloch-Michel ('Lombard'), of which Bloch learned from meeting with 'Chardon', a Combat member who recently arrived from Haute-Savoie and an associate of his other nephew Henri.[157] His nephew Jean, who was released in late May, admitted having given Bloch's address away;[158] he never mentioned Bloch in his memoirs and was later held responsible for his arrest.[159] 'Chardon' was cleared of suspicion by Alban Vistel, the regional head of MUR whom Bloch was replacing due to sickness, in an investigation which found that two other members of the network ('Chatoux' of Combat and Madame Jacotot) were seen in a Gestapo car after their arrests.[160] On the morning of Bloch's arrest his route was betrayed to the Gestapo, who already had his description but failed to seize him at home, by a local bakery owner.[151] A radio transmitter and some Resistance papers were found in his apartment on 9 March, after a key part of the archives had been entrusted for safekeeping by 'Chardon' to Jacotot, who was herself arrested on that day.[151][1] Bloch's arrest was touted in the Nazi and collaborationist press (such as Aujourd'hui, Le Matin and Le Petit Parisien) as a major success in the breaking up of a "Communist-terrorist" group financed from London and Moscow, led by a "Jew who had taken the pseudonym of a French southern city".[161][162] The minister of information and propaganda Philippe Henriot boasted afterwards of destroying "the capital of the Resistance" in Lyon,[161] and the German ambassador Otto Abetz telegraphed about Bloch's arrest to Berlin.[162]

Bloch was detained in Montluc prison.[114][163] As a key Resistance figure, he was interrogated and tortured daily in the Lyon Gestapo headquarters at the School of Military Health in avenue Berthelot by Klaus Barbie's men, suffering beatings, pneumonia from ice-baths, broken ribs and wrists.[164][165][1] It was later claimed that he gave away no information to his interrogators, and while incarcerated taught French history to other inmates.[72] His interrogation protocol, which he signed three days before his death, contained the names of Resistance leaders already captured or in Algiers with General de Gaulle.[166]

In the meantime, the Allies had invaded Normandy on 6 June 1944[72] and Nazis wanted to evacuate Vichy and "liquidate their holdings".[1] This meant disposing of as many prisoners as they could.[72] Between May and June 1944 the Nazi occupying forces murdered around 700 prisoners.[72] Bloch was among the twenty-eight men shot in the back with submachine guns in groups of four by Sicherheitsdienst[167] in a meadow at Les Roussilles near Saint-Didier-de-Formans on the night of 16 June 1944.[168][169][114][72][101][1][72] The bodies were discovered on the next day and examined by French forensic authorities from Lyon.[170] For some time Bloch's death was merely a "dark rumour".[88] His wife Simonne, who suffered from undiagnosed stomach cancer, died on 2 July 1944.[170][171] Eventually his personal effects were identified in September 1944 by his daughter Alice and sister-in-law Hélène Weill, who notified Febvre, and his death was officially announced on 1 November.[172] Weill also reported that Bloch's country residence in Fougères, deserted by his family in May 1944, had since been occupied and looted, allegedly by Communist partisans.[173]

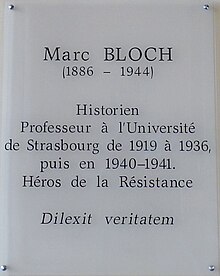

The autobiographical speech read at Bloch's burial acknowledged his Jewish ancestry while affirming a French identity.[174][note 17] According to his instructions, on his grave was to be carved his epitaph dilexi veritatem ("I have loved the truth").[175]

Bibliography

[edit]- 'A Contribution towards a Comparative History of European Societies', in Land and Work in Medieval Europe. London, 1967.

- 'Memoire collective', Revue de synthese historique 40 (1925): 73-83.

- 'Technical Change as a Problem of Collective Psychology', Journal of Normal and Pathological Psychology (1948): 104-15. Reprinted in Bloch, 1967, 124-35.

- Apologie pour l'histoire. Paris, 1949. English trans., The Historian's Craft. Manchester, 1954.

- L'Etrange defaite, Paris, 1946. English trans., Strange Defeat. London, 1949.

- L'Ile de France Paris, 1913. English trans., The Ile de France. London, 1971.

- La Societe feodale, 2 vols. Paris, 1939-40. English trans., Feudal Society, 2 vols. London, 1961.

- Land and Work in Medieval Europe. London, 1967

Historical method and approach

[edit]The microscope is a marvellous instrument for research; but a heap of microscopic slides does not constitute a work of art.[176]

Marc Bloch

Davies says Bloch was "no mean disputant"[126] in historiographical debate, often reducing an opponent's argument to its most basic weaknesses.[126] His approach was a reaction against the prevailing ideas within French historiography of the day which, when he was young, were still very much based on that of the German School, pioneered by Leopold von Ranke.[note 18] Within French historiography this led to a forensic focus on administrative history as expounded by historians such as Ernest Lavisse.[78] While he acknowledged his and his generation of historians' debt to their predecessors, he considered that they treated historical research as being little more meaningful than detective work. Bloch later wrote how, in his view, "There is no waste more criminal than that of erudition running ... in neutral gear, nor any pride more vainly misplaced than that in a tool valued as an end in itself".[178][179] He believed it was wrong for historians to focus on the evidence rather than the human condition of whatever period they were discussing.[178] Administrative historians, he said, understood every element of a government department without understanding anything of those who worked in it.[78]

Bloch was very much influenced by Ferdinand Lot, who had already written comparative history,[58] and by the work of Jules Michelet and Fustel de Coulanges with their emphasis on social history, Durkheim's sociological methodology, François Simiand's social economics, and Henri Bergson's philosophy of collectivism.[58] Bloch's emphasis on using comparative history harked back to the Enlightenment, when writers such as Voltaire and Montesquieu decried the notion that history was a linear narrative of individuals and pushed for greater use of philosophy in studying the past.[68] Bloch condemned the "German-dominated" school of political economy, which he considered "analytically unsophisticated and riddled with distortions".[180] Equally condemned were then-fashionable ideas on racial theories of national identity.[33] Bloch believed that political history on its own could not explain deeper socioeconomics trends and influences.[181]

Bloch did not see social history as being a separate field within historical research. Rather, he saw all aspects of history to be inherently a part of social history. By definition, all history was social history,[182] an approach he and Febvre termed "histoire totale",[43] not a focus on points of fact such as dates of battles, reigns, and changes of leaders and ministries, and a general confinement by the historian to what he can identify and verify.[183] Bloch explained in a letter to Pirenne that, in Bloch's eyes, the historian's most important quality was the ability to be surprised by what he found—"I am more and more convinced of this", he said; "damn those of us who believe everything is normal!"[184]

For Bloch history was a series of answers, albeit incomplete and open to revision, to a series of intelligently posed questions.[185]

Bloch identified two types of historical eras: the generational era and the era of civilisation: these were defined by the speed with which they underwent change and development. In the latter type of period, which changed gradually, Bloch included physical, structural, and psychological aspects of society, while the generational era could experience fundamental change over a relatively few generations.[186] Bloch founded what modern French historians call the "regressive method" of historical scholarship. This method avoids the necessity of relying solely on historical documents as a source, by looking at the issues visible in later historical periods and drawing from them what they may have looked like centuries earlier. Davies says this was particularly useful in Bloch's study of village communities as "the strength of communal traditions often preserves earlier customs in a more or less fossilized state".[187] Bloch studied peasant tools in museums, observed their use in work, and discussed the objects with the people who used them.[188] He believed that in observing a plough or an annual harvest one was observing history, as more often than not both the technology and the technique were much the same as they had been hundreds of years earlier.[29] However, the individuals themselves were not his focus; instead, he focused on "the collectivity, the community, the society".[189] He wrote about the peasantry, rather than the individual peasant; says Lyon, "he roamed the provinces to become familiar with French agriculture over the long term, with the contours of peasant villages, with agrarian routine, its sounds and smells.[42] Bloch claimed that both fighting alongside the peasantry in the war and his historical research into their history had shown him "the vigorous and unwearied quickness"[10] of their minds.[10]

Bloch described his area of study as the comparative history of European society and explained why he did not identify himself as a medievalist: "I refuse to do so. I have no interest in changing labels, nor in clever labels themselves, or those that are thought to be so."[96] He did not leave a full study of his methodology, although it can be effectively reconstructed piecemeal.[190] He believed that history was the "science of movement",[191] but did not accept, for example, the aphorism that one could protect against the future by studying the past.[132] His work did not use a revolutionary approach to historiography; rather, he wished to combine the schools of thinking that preceded him into a new broad approach to history[192] and, as he wrote in 1926, to bring to history "ce murmure qui n'était pas de la mort", ("the whisper that was not death').[121] He criticised what he called the "idol of the origins",[193] where historians concentrate overly hard on the formation of something to the detriment of studying the thing itself.[193]

Bloch's comparative history led him to tie his researches in with those of many other schools: social sciences, linguistics, philology, comparative literature, folklore, geography, and agronomy.[43] Similarly, he did not restrict himself to French history. At various points in his writings, Bloch commented on medieval Corsican, Finnish, Japanese, Norwegian and Welsh history.[194] R. R. Davies has compared Bloch's intelligence with what he calls that of "the Maitland of the 1890s", regarding his breadth of reading, use of language and multidisciplinary approach.[126] Unlike Maitland, however, Bloch also wished to synthesise scientific history with narrative history. According to Stirling, he managed to achieve "an imperfect and volatile imbalance" between them.[45] Bloch did not believe that it was possible to understand or recreate the past by the mere act of compiling facts from sources; rather, he described a source as a witness, "and like most witnesses", he wrote, "it rarely speaks until one begins to question it".[195] Likewise, he viewed historians as detectives who gathered evidence and testimony, as juges d'instruction (examining magistrates) "charged with a vast enquiry of the past".[102] Bloch was also an early theorist in the field of the preservation of collective memory.[196]

Areas of interest

[edit]If we embark upon our reexamination of Bloch by viewing him as a novel and restless synthesizer of traditions that had previously seemed incommensurable, a more nuanced image than the traditionally held one emerges. Examined through this lens as a quixotic idealist, Bloch is revealed as the undogmatic creator of a powerful – and perhaps ultimately unstable – method of historical innovation that can most accurately be described as quintessentially modern.[6]

Katherine Stirling

Bloch was not only interested in periods or aspects of history but in the importance of history as a subject, regardless of the period, of intellectual exercise. Davies writes, "he was certainly not afraid of repeating himself; and, unlike most English historians, he felt it his duty to reflect on the aims and purposes of history".[71] Bloch considered it a mistake for the historian to confine himself overly rigidly to his own discipline. Much of his editorialising in Annales emphasised the importance of parallel evidence to be found in neighbouring fields of study, especially archaeology, ethnography, geography, literature, psychology, sociology, technology,[197] air photography, ecology, pollen analysis and statistics.[198] In Bloch's view, this allowed not just a broader field of study, but a far more comprehensive understanding of the past than would be possible from relying solely on historical sources.[197] Bloch's favourite example of how technology impacts society was the watermill. This can be summed up as illustrating how it was known of but little used in the classical period; it became an economic necessity in the early medieval period; and finally, in the later Middle Ages, it represented a scarce resource increasingly concentrated in the nobility's hands.[29][note 19]

Bloch also emphasised the importance of geography in the study of history, and particularly in the study of rural history.[195] He suggested that, fundamentally, they were the same subjects, although he criticised geographers for failing to take historical chronology[26] or human agency into account. Using a farmer's field as an example, he described it as "fundamentally, a human work, built from generation to generation".[199] Bloch also condemned the view that rural life was immobile. He believed that the Gallic farmer of the Roman period was inherently different from his 18th-century descendants, cultivating different plants, in a different way.[200] He saw England and France's agricultural history as developing similarly, and, indeed, discovered an Enclosure Movement in France throughout the 15th, 16th, and 17th centuries on the basis that it had been occurring in England in similar circumstances.[201] Bloch also took a deep interest in the field of linguistics and their use of the comparative method. He believed that using the method in historical research could prevent the historian from ignoring the broader context in the course of his detailed local researches:[202] "a simple application of the comparative method exploded the ethnic theories of historical institutions, beloved of so many German historians".[78]

Block was multilingual, and impressed contemporaries with the breadth of his knowledge and erudition and his facility in both ancient and modern languages. His clear prose and his methodology of formulating historical issues in social terms left a strong impact on the discipline of history. Bloch dreamed of a borderless world, where the constraints of geography, time, and academic discipline could be dismantled and history could be addressed from a global perspective.[203]

Personal life

[edit]

Bloch was not a tall man, being 5 feet 5 inches (1.65 m) in height.[100] He was an elegant dresser. Eugen Weber has described Bloch's handwriting as "impossible".[100] He had expressive blue eyes, which could be "mischievous, inquisitive, ironic and sharp".[56] Febvre later said that when he first met Bloch in 1902, he found a slender young man with "a timid face".[29] Bloch was proud of his family's history of defending France: he later wrote, "My great-grandfather was a serving soldier in 1793; ... my father was one of the defenders of Strasbourg in 1870 ... I was brought up in the traditions of patriotism which found no more fervent champions than the Jews of the Alsatian exodus".[204]

Bloch was a committed supporter of the Third Republic and politically left-wing.[20] He was not a Marxist, although he was impressed by Karl Marx himself, whom he thought was a great historian if possibly "an unbearable man" personally.[64] He viewed contemporary politics as purely moral decisions to be made.[174] He did not, however, let it enter into his work; indeed, he questioned the very idea of a historian studying politics.[114] He believed that society should be governed by the young, and, although politically he was a moderate, he noted that revolutions generally promote the young over the old: "even the Nazis had done this, while the French had done the reverse, bringing to power a generation of the past".[132] According to Epstein, following the First World War, Bloch presented a "curious lack of empathy and comprehension for the horrors of modern warfare",[87] while John Lewis Gaddis has found Bloch's failure to condemn Stalinism in the 1930s "disturbing".[205] Gaddis suggests that Bloch had ample evidence of Stalin's crimes and yet sought to shroud them in utilitarian calculations about the price of what he called 'progress'".[205]

Although Bloch was very reserved[56]—and later acknowledged that he had generally been old-fashioned and "timid" with women[110]—he was good friends with Lucien Febvre and Christian Pfister.[4] In July 1919 he married Simonne Vidal, a "cultivated and discreet, timid and energetic"[86] woman, at a Jewish wedding.[87] Her father was the Inspecteur-Général de Ponts et Chaussées, and a very prosperous and influential man. Undoubtedly, says Friedman, his wife's family wealth allowed Bloch to focus on his research without having to depend on the income he made from it.[64] Bloch was later to say he had found great happiness with her, and that he believed her to have also found it with him.[110] They had six children together,[47] four sons and two daughters.[142] The eldest two were a daughter Alice,[117][79] and a son, Étienne.[79] As his father had done with him, Bloch took a great interest in his children's education, and regularly helped with their homework.[86] He could, though, be "caustically critical"[117] of his children, particularly Étienne. Bloch accused him in one of his wartime letters of having poor manners, being lazy and stubborn, and of being possessed occasionally by "evil demons".[117] Regarding the facts of life, Bloch told Etienne to attempt always to avoid what Bloch termed "contaminated females".[117]

Bloch was agnostic, if not atheist, in matters of religion.[87] His son Étienne later said of his father, "in his life as well as his writings not even the slightest trace of a supposed Jewish identity" can be found. "Marc Bloch was simply French".[206] Some of his pupils believed him to be an Orthodox Jew, but Loyn says this is incorrect. While Bloch's Jewish roots were important to him, this was the result of the political tumult of the Dreyfuss years, said Loyn: that "it was only anti-semitism that made him want to affirm his Jewishness".[142]

Bloch's brother Louis became a doctor, and eventually the head of the diphtheria section of the Hôpital des Enfants-Malades. Louis died prematurely in 1922.[3] Their father died in March the following year.[3] Following these deaths, Bloch took on responsibility for his aging mother as well as his brother's widow and children.[86] Eugen Weber has suggested that Bloch was probably a monomaniac[105] who, in Bloch's own words, "abhorred falsehood".[117] He also abhorred, as a result of both the Franco-Prussian war and more recently the First World War,[2] German nationalism. This extended to that country's culture and scholarship, and is probably the reason he never debated with German historians.[65] Indeed, in Bloch's later career, he rarely mentioned even those German historians with whom he must, professionally, have felt an affinity, such as Karl Lamprecht. Lyon says Lamprecht had denounced what he saw as the German obsession with political history and had focused on art and comparative history, thus "infuriat[ing] the Rankianer".[2] Bloch once commented, on English historians, that "en Angleterre, rien qu'en Angleterre"[85] ("in England, only England"). He was not, though, particularly critical of English historiography, and respected the long tradition of rural history in that country as well as more materially the government funding that went into historical research there.[190]

Legacy

[edit]

It is possible, argues Weber, that had Bloch survived the war, he would have been a candidate for Minister of Education in a post-war government and would have reformed the education system he had condemned for losing France the war in 1940.[207] Instead, in 1948, his son Étienne offered the Archives Nationales his father's papers for their repository, but they rejected the offer. As a result, the material was placed in the vaults of the École Normale Supérieure, "where it lay untouched for decades".[79]

Intellectual historian Peter Burke named Bloch the leader of what he called the "French Historical Revolution",[208] and Bloch became an icon for the post-war generation of new historians.[49] Although he has been described as being, to some extent, the object of a cult in both England and France[74]—"one of the most influential historians of the twentieth century"[209] by Stirling, and "the greatest historian of modern times" by John H. Plumb[1]—this is a reputation mostly acquired postmortem.[210] Henry Loyn suggests it is also one which would have amused and amazed Bloch.[194] According to Stirling, this posed a particular problem within French historiography when Bloch effectively had martyrdom bestowed upon him after the war, leading to much of his work being overshadowed by the last months of his life.[192] This led to "indiscriminate heaps of praise under which he is now almost hopelessly buried".[101] This is partly at least the fault of historians themselves, who have not critically re-examined Bloch's work but rather treat him as a fixed and immutable aspect of the historiographical background.[192]

At the turn of the millennium "there is a woeful lack of critical engagement with Marc Bloch's writing in contemporary academic circles" according to Stirling.[192] His legacy has been further complicated by the fact that the second generation of Annalists led by Fernand Braudel has "co-opted his memory",[192][note 20] combining Bloch's academic work and Resistance involvement to create "a founding myth".[212] The aspects of his life which made Bloch easy to beatify have been summed up by Henry Loyn as "Frenchman and Jew, scholar and soldier, staff officer and Resistance worker ... articulate on the present as well as the past".[213]

The first critical biography of Bloch did not appear until Carole Fink's Marc Bloch: A Life in History was published in 1989.[210] This, wrote S. R. Epstein, was the "professional, extensively researched and documented" story of Bloch's life, and, he commented, probably had to "overcome a strong sense of protectiveness among the guardians of Bloch's and the Annales' memory".[210] Since then, continuing scholarship—such as that by Stirling, who calls Bloch a visionary, although a "flawed" one[209]—has been more critically objective of Bloch's recognisable weaknesses. For example, although he was a keen advocate for chronological precision and textual accuracy, his only major work in this area, a discussion of Osbert of Clare's Life of Edward the Confessor, was subsequently "seriously criticised"[126] by later experts in the field such as R. W. Southern and Frank Barlow;[4] Epstein later suggested Bloch was "a mediocre theoretician but an adept artisan of method".[214] Colleagues who worked with him occasionally complained that Bloch's manner could be "cold, distant, and both timid and hypocritical"[207] due to the strong views he had held on the failure of the French education system.[207] Bloch's reduction of the role of individuals, and their personal beliefs, in changing society or making history has been challenged.[215] Even Febvre, reviewing Feudal Society on its post-war publication, suggested that Bloch had unnecessarily ignored the individual's role in societal development.[122]

Bloch has also been accused of ignoring unanswered questions and presenting complete answers when they are perhaps not deserved,[36] and of sometimes ignoring internal inconsistencies.[192] Andrew Wallace-Hadrill has also criticised Bloch's division of the feudal period into two distinct times as artificial. He also says Bloch's theory on the transformation of blood ties into feudal bonds does not correspond with either chronological evidence or what is known of the nature of the early family unit.[36] Bloch seems to have occasionally ignored, whether accidentally or deliberately, important contemporaries in his field. Richard Lefebvre des Noëttes, for example, who founded the history of technology as a new discipline, built new harnesses from medieval illustrations, and drew histographical conclusions. Bloch, though, does not seem to have acknowledged the similarities between his and Lefebvre's approaches to physical research, even though he cited much earlier historians.[216] Davies argued that there was a sociological aspect to Bloch's work which often neutralised the precision of his historical writing;[36] as a result, he says, those of Bloch's works with a sociological conception, such as Feudal Society, have not always "stood the test of time".[202]

Comparative history, too, still proved controversial many years after Bloch's death,[182] and Bryce Lyon has posited that, had Bloch survived the war, it is very likely that his views on history—already changing in the early years of the second war, just as they had done in the aftermath of the first—would have re-adjusted themselves against the very school he had founded.[2] Stirling suggests what distinguished Bloch from his predecessors was that he effectively became a new kind of historian, who "strove primarily for transparency of methodology where his predecessors had striven for transparency of data"[60] while continuously critiquing himself at the same time.[60] Davies suggests his legacy lies not so much in the body of work he left behind him, which is not always as definitive as it has been made out to be, but the influence he had on "a whole generation of French historical scholarship".[36] Bloch's emphasis on how rural and village society has been neglected by historians in favour of the lords and manorial courts that ruled them influenced later historians such as R. H. Hilton in the study of the economics of peasant society.[187] Bloch's combination of economics, history, and sociology was "forty years before it became fashionable", argues Daniel Chirot, which he says could make Bloch a founding father of post-war sociology scholarship.[217]

The English-language journal Past & Present, published by Oxford University Press, was a direct successor to the Annales, suggests Loyn.[218] Michel Foucault said of the Annales School, "what Bloch, Febvre and Braudel have shown for history, we can show, I believe, for the history of ideas".[219] Bloch's influence spread beyond historiography after his death. In the 2007 French presidential election, Bloch was quoted many times. For example, candidates Nicolas Sarkozy and Marine Le Pen both cited Bloch's lines from Strange Defeat: "there are two categories of Frenchmen who will never really grasp the significance of French history: those who refuse to be thrilled by the Consecration of our Kings at Reims, and those who can read unmoved the account of the Festival of Federation".[220][note 21] In 1977, Bloch received a state reburial; streets schools and universities have been named after him,[222] and the centennial of Bloch's birth was celebrated at a conference held in Paris in June 1986. It was attended by academics of various disciplines, particularly historians and anthropologists.[210]

Awards

[edit]- Knight of the Legion of Honour

- Croix de Guerre 1914-1918, 4 mentions in despatches (2 bronze and 2 silver)

- Croix de Guerre 1939-1945, 1 mention in despatches (1 silver-gilt)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Gustave Bloch, author of La Gaule Romaine, was a noted historian in his own right, and R. R. Davies suggests his son's "intellectual mentor; [it] was doubtless from him that Marc Bloch derived his interest in rural history and in the problem of the emergence of medieval society from the Roman world."[4]

- ^ Gustave Bloch personally took part in the defence of Strasbourg in September 1870.[9]

- ^ The latter generation included nationalist Boulangists and crises such as the Panama scandals in the last decade of the nineteenth century.[14]

- ^ In The Historian's Craft, Bloch describes himself as one of "the last of the generation of the Dreyfus Affair".[16]

- ^ His father's nickname was a reference to the skeleton of a megatherium which was housed in the ÉNS.[3]

- ^ This road is now the Avenue de Maréchal Leclerc.[31]

- ^ This was nicknamed the Nouvelle Sorbonne by contemporaries, and has been described by Friedman as "a residence for a very select group of doctoral students"; with an intake of only five students annually, residency lasted three years. During Bloch's tenure, the director of Fondation Thiers was the philosopher Emile Boutroux.[32]

- ^ Bloch did, however, continually refer back to this research throughout the rest of his career, and Guy Fourquin's 1963 monograph Les campagnes de la rdgion parisienne li la fin du moyen age effectively completed the study.[36]

- ^ Bloch later recalled that he had seen only one exception to this collective spirit, and that that was a by "'scab', by which I mean a non-unionist employed as a strike-breaker".[10]

- ^ The transfer of Strasbourg University from German to French ownership provided the opportunity to recruit, as H. Stuart Hughes put it, "de novo a faculty of distinction".[63] Colleagues of Bloch at Strasbourg included archaeologists, psychologists, and sociologists such as Maurice Halbwachs, Charles Blondel, Gabriel le Bras and Albert Grenier; together they took part in a "remarkable interdisciplinary seminar".[62] Bloch himself was a believer in the assimilation of Alsace and the encouragement of "anti-German cultural revanchism".[8]

- ^ Bloch's ideas on comparative history were particularly popular in Scandinavia, and he regularly returned to them in his subsequent lectures there.[75]

- ^ This appeared in 1941. Bloch's chapter was "The Rise of Dependent Cultivation and Seignorial Institutions" in the first volume.[89]

- ^ There was strong mutual respect between Luzzatto and Bloch and Febvre, who regularly reviewed his work in the Annales, and for which he had most recently written an article in 1937.[104]

- ^ Known as the drôle de guerre in French.[47]

- ^ Notwithstanding his respect for British historians, says Lyon, Bloch, like many of his compatriots, was anglophobic; he described the British soldier as naturally "a looter and a lecher: that is to say, the two vices which the French peasant finds it hard to forgive when both are satisfied to the detriment of his farmyard and his daughters",[109] and English officers as being imbued with an "old crusted Tory tradition".[109]

- ^ Bloch questioned the lack of a collective French spirit between the wars in Strange Defeat: "we were all of us either specialists in the social sciences or workers in scientific laboratories, and maybe the very disciplines of those employments kept us, by a sort of fatalism, from embarking on individual action".[150][149]

- ^ Davies suggests that the speech he self-described with at his funeral may be unpleasant hearing to some historians in the words' stridency and emotion. However, he also notes the necessity of remembering the context, that "they are the words of a Jew by birth writing in the darkest hour of France's history and that Bloch never confused patriotism with a narrow, exclusive nationalism".[174] In Strange Defeat, Bloch had written that the only time he had ever emphasised his ethnicity was "in the face of an antisemite".[118]

- ^ Von Ranke summed up his philosophy of history in the dictum: "the strict presentation of the facts, contingent and unattractive though they may be, is undoubtedly the supreme law".[177]

- ^ *More on watermill*

- ^ They did not do this with the intention of suppressing discussion of Bloch's ideas, wrote Karen Stirling, but "it is easy for contemporary scholars to confuse Bloch's own individualistic work as a historian with that of his structuralist successors". In other words, to apply to Bloch's views those who followed him with, in some cases, rather different interpretations of those views.[211]

- ^ The context in which Bloch wrote this passage was slightly different to that given it by the two candidates, who were both on the right of the political centre. But, says Peter Schöttler, Bloch "had already coined this aphorism during the First World War and given it a significant heading: 'On the history of France and why I am not a conservative'".[221]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Weber 1991, p. 244.

- ^ a b c d e f Lyon 1985, p. 183.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Friedman 1996, p. 7.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Davies 1967, p. 267.

- ^ a b Fink 1989, p. 8.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Stirling 2007, p. 527.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 16.

- ^ a b Epstein 1993, p. 280.

- ^ a b Fink 1998, p. 41.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lyon 1985, p. 184.

- ^ Fink 1995, p. 205.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 17.

- ^ Febvre 1947, p. 172.

- ^ a b c Friedman 1996, p. 6.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 19.

- ^ Bloch 1963, p. 154.

- ^ Hughes-Warrington 2015, p. 10.

- ^ a b Fink 1989, p. 24.

- ^ a b Friedman 1996, p. 4.

- ^ a b c d e Schöttler 2010, p. 415.

- ^ a b c d e f Lyon 1987, p. 198.

- ^ Fink 1989, pp. 24–25.

- ^ a b Fink 1989, p. 22.

- ^ Gat 1992, p. 93.

- ^ Friedman 1996, p. 3.

- ^ a b c Davies 1967, p. 275.

- ^ Baulig 1945, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Fink 1989, p. 40.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hughes 2002, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Fink 1989, p. 43.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Weber 1991, p. 245.

- ^ Friedman 1996, pp. 74–75.

- ^ a b Fink 1989, p. 44.

- ^ a b Fink 1989, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Hughes-Warrington 2015, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f Davies 1967, p. 269.

- ^ a b Fink 1989, p. 11.

- ^ Bloch 1980, p. 52.

- ^ a b Fink 1989, p. 26.

- ^ a b Hochedez 2012, p. 62.

- ^ a b c d Hochedez 2012, p. 61.

- ^ a b c Lyon 1987, p. 199.

- ^ a b c d e Lyon 1987, p. 200.

- ^ Burguière 2009, p. 38.

- ^ a b c Stirling 2007, p. 528.

- ^ Lyon 1985, p. 185.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Fink 1998, p. 40.

- ^ Epstein 1993, p. 277.

- ^ a b Sreedharan 2004, p. 259.

- ^ a b Loyn 1999, p. 162.

- ^ Hochedez 2012, p. 64.

- ^ Loyn 1999, p. 164.

- ^ Hochedez 2012, p. 63.

- ^ a b Bloch 1980, p. 14.

- ^ Epstein 1993, pp. 276–277.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Friedman 1996, p. 10.

- ^ Bloch 1927, p. 176.

- ^ a b c Lyon 1985, p. 181.

- ^ Huppert 1982, p. 510.

- ^ a b c d e f Stirling 2007, p. 529.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 84.

- ^ a b Epstein 1993, p. 279.

- ^ Hughes 2002, p. 121.

- ^ a b c d e f Friedman 1996, p. 11.

- ^ a b Epstein 1993, p. 278.

- ^ Rhodes 1999, p. 111.

- ^ a b c d e Fink 1995, p. 207.

- ^ a b Sreedharan 2004, p. 258.

- ^ Lyon 1987, p. 201.

- ^ a b c d Lyon 1985, p. 182.

- ^ a b Davies 1967, p. 270.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fink 1995, p. 209.

- ^ Lyon 1985, pp. 181–182.

- ^ a b Davies 1967, p. 265.

- ^ Raftis 1999, p. 73 n.4.

- ^ a b c Epstein 1993, p. 275.

- ^ a b c d e Stirling 2007, p. 530.

- ^ a b c d Davies 1967, p. 280.

- ^ a b c d e Epstein 1993, p. 274.

- ^ a b Huppert 1982, p. 512.

- ^ a b Lyon 1987, p. 202.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 31.

- ^ Dosse 1994, p. 107.

- ^ Sewell 1967, p. 210.

- ^ a b Davies 1967, p. 266.

- ^ a b c d Friedman 1996, p. 12.

- ^ a b c d e f g Epstein 1993, p. 276.

- ^ a b c Burguière 2009, p. 39.

- ^ Lyon 1987, p. 204.

- ^ Fink 1998, pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b Weber 1991, p. 249 n..

- ^ Bloch 1963, p. 39.

- ^ a b c Dosse 1994, p. 43.

- ^ Bianco 2013, p. 248.

- ^ a b c Burguière 2009, p. 47.

- ^ a b Raftis 1999, p. 63.

- ^ a b c Weber 1991, p. 254.

- ^ Weber 1991, pp. 254–255.

- ^ Weber 1991, p. 255.

- ^ a b c d e f Weber 1991, p. 256.

- ^ a b c d Stirling 2007, p. 531.

- ^ a b Weber 1991, p. 250.

- ^ Epstein 1993, pp. 274–275.

- ^ Lanaro 2006.

- ^ a b c Weber 1991, p. 249.

- ^ Huppert 1982, p. 514.

- ^ a b Fink 1998, p. 45.

- ^ a b Stirling 2007, p. 533.

- ^ a b c Lyon 1985, p. 188.

- ^ a b c Fink 1998, p. 43.

- ^ Fink 1998, p. 44.

- ^ Fink 1998, p. 48.

- ^ a b Fink 1998, p. 49.

- ^ a b c d Dosse 1994, p. 44.

- ^ a b c d e f g Fink 1995, p. 208.

- ^ Burguière 2009, p. 48.

- ^ a b c d e f Fink 1998, p. 42.

- ^ a b Bloch 1949, p. 23.

- ^ a b Kaye 2001, p. 97.

- ^ Lyon 1985, p. 189.

- ^ a b Davies 1967, p. 281.

- ^ a b Hughes-Warrington 2015, p. 15.

- ^ Fink 1998, p. 39.

- ^ Birnbaum 2007, p. 251 n.92.

- ^ a b c Schöttler 2022, p. 5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Davies 1967, p. 268.

- ^ a b Schöttler 2022, p. 6.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 279–280.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 249–250, 265–267.

- ^ a b Weber 1991, pp. 253–254.

- ^ Levine 2010, p. 15.

- ^ a b c Chirot 1984, p. 43.

- ^ a b c Fink 1989, p. 279.

- ^ Rioux 1987, p. 44.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 261–262.

- ^ Burguière 2009, p. 43.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 262.

- ^ a b Burguière 2009, p. 45.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 268–269.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 276.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 276–277.

- ^ a b c Loyn 1999, p. 163.

- ^ Geremek 1986, p. 1103.

- ^ Geremek 1986, p. 1105.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 297-298.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 297.

- ^ a b c Bloch, Etienne (25 April 1997), Marc Bloch, 1886-1944: une biographie impossible (Communication au colloque de Berlin, 25 avril 1997), Clioweb

- ^ Geremek 1986, p. 1104.

- ^ a b Lyon 1985, p. 186.

- ^ Bloch 1980, pp. 172–173.

- ^ a b c Fink 1989, p. 315.

- ^ Freire 2015, p. 170 n. 60.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 311.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 312.

- ^ Schöttler 2022, p. 8, 14.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 312, 314–315.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 312, 314.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 318.

- ^ Schöttler 2022, p. 9, 12.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 317–318.

- ^ a b Fink 1989, p. 316.

- ^ a b Schöttler 2022, p. 8.

- ^ Schöttler 2022, p. 10.

- ^ Fink 1989, p. 318–319.

- ^ Schöttler 2022, p. 10–11.

- ^ Schöttler 2022, p. 13, 15.