Pablo Escobar

This article may contain an excessive number of citations. (November 2024) |

Pablo Escobar | |

|---|---|

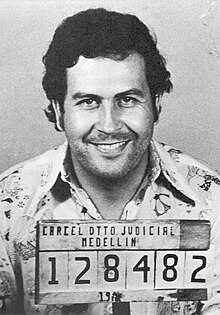

Escobar in a 1976 mugshot | |

| Born | Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria 1 December 1949 Rionegro, Colombia |

| Died | 2 December 1993 (aged 44) Medellín, Colombia |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wound to the head |

| Resting place | Monte Sacro Cemetery |

| Spouse |

Maria Victoria Henao

(m. 1976) |

| Children |

|

| Parent(s) | Abel de Jesús Escobar Echeverri[1][2] Hermilda de los Dolores Gaviria Berrío[3][4] |

| Relatives | José Obdulio Gaviria Gustavo Gaviria |

| Criminal charge | Drug trafficking, money laundering, murder, terrorism, bribery, smuggling, extortion, political corruption. |

| Other names |

|

| Organization | Medellín cartel |

| Conviction(s) | Illegal drug trade, assassinations, bombing, bribery, racketeering, murder |

| Criminal penalty | Five years' imprisonment |

| Signature | |

| |

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria (/ˈɛskəbɑːr/; Spanish: [ˈpaβlo eskoˈβaɾ]; 1 December 1949 – 2 December 1993) was a Colombian drug lord, narcoterrorist, and politician who was the founder and sole leader of the Medellín Cartel.[5][6] Dubbed "the king of cocaine", Escobar was one of the wealthiest criminals in history, having amassed an estimated net worth of US$30 billion by the time of his death—equivalent to $70 billion as of 2022—while his drug cartel monopolized the cocaine trade into the United States in the 1980s and early 1990s.[7][8]

Born in Rionegro into a peasant family and raised in Medellín, Escobar studied briefly at Universidad Autónoma Latinoamericana of Medellín but left without graduating; he instead began engaging in criminal activity, selling illegal cigarettes and fake lottery tickets, as well as participating in motor vehicle theft. In the early 1970s, he began to work for various smugglers.

In 1976, forming alliances with Gonzalo Rodríguez Gacha, Carlos Lehder, and Jorge Luis Ochoa and his clan, Escobar founded the Medellín Cartel, which distributed powder cocaine. He also established the first smuggling routes from Peru, Bolivia, and Ecuador through Colombia and into the United States. Escobar's infiltration into the U.S. created exponential demand for cocaine, and by the 1980s, it was estimated Escobar led monthly shipments of 70 to 80 tons of cocaine into the country from Colombia, controlling more than 80% of the world's production of the drug and 60% of the illicit market in the United States.[9] As a result, Escobar amassed an immense fortune, which amounted to around eight billion dollars between assets and cash; according to Forbes, for seven consecutive years, he was one of the richest people in the world.[7][10][11][12][13]

In the 1982 Colombian parliamentary election, to excuse his immeasurable capital, Escobar was elected as an alternate member of the Chamber of Representatives as part of the Liberal Party. Through this, he was responsible for community projects such as the construction of houses and football fields, which gained him popularity among the locals of the towns that he frequented; however, Escobar's political ambitions were thwarted by the Colombian and U.S. governments, constantly battled rival cartels domestically and abroad, leading to massacres and the murders of police officers, judges, locals, and prominent politicians.[14] who routinely pushed for his arrest, with Escobar widely believed to have orchestrated the Avianca Flight 203 and DAS Building bombings in retaliation.

In 1989, after several attempts at negotiation, multiple kidnappings, and selective assassinations of judges and public officials, the Medellín Cartel with Escobar at its helm declared total war against the government.[15][16] Escobar organized and financed an extensive army of hitmen, who assassinated key figures for the Colombian institutionality, such as the liberal leader Luis Carlos Galán, and perpetrated indiscriminate terrorist acts, such as the use of car bombs in Colombia's main cities. This campaign of narcoterrorism destabilized the country and made Escobar the most wanted criminal in the world at the beginning of the nineties.[17][18] Escobar was responsible for the murder of 657 police officers between 1989 and 1993,[19][20][21] and fierce clashes against the Cali Cartel,[22][23] the Magdalena Medio Antioquia paramilitary groups, and Los Pepes.

In 1991, after the consummation of the National Constituent Assembly, which gave Colombia a new constitution and the prohibition of the extradition of nationals, Escobar surrendered to authorities and was sentenced to five years' imprisonment on multiple charges; however, he struck a deal of no extradition with Colombian President César Gaviria, along with the ability to be housed in his self-built prison, La Catedral. In 1992, when authorities attempted to move Escobar to a more standard holding facility after confirming that he had continued to commit crimes while imprisoned, Escobar escaped and went into hiding, leading to a nationwide manhunt.[24] As a result, the Medellín Cartel crumbled, and in 1993, Escobar was killed in his hometown by Colombian National Police, a day after his 44th birthday.[25]

Escobar's legacy remains controversial; while many denounce the heinous nature of his crimes, he was seen as a "Robin Hood-like" figure for many in Colombia, as he provided many amenities to the poor. His killing was mourned and his funeral attended by over 25,000 people.[26] Additionally, his private estate, Hacienda Nápoles, has been transformed into a theme park.[27] His life has also served as inspiration for or has been dramatized widely in film, television, and in music.

Early life

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was born on 1 December 1949 in the small village of El Tablazo near Rionegro, Antioquia Department. He belonged to the Paisa ethnic subgroup. His family was of Spanish origin, specifically from the Basque Country, and also had Italian roots.[28] He was the second of seven children and grew up in poverty.[29][30][31][32] His father was a small farmer and his mother was a teacher, and his siblings in order of birth were Roberto de Jesus 'El Osito',[33] Gloria Inés,[34] Argemiro,[35] Alba Marina,[36] Luz María[37] and Luis Fernando (the latter born in 1958 and murdered at the age of 19 in 1977).[38]

Escobar's maternal grandfather, Roberto Gaviria Cobaleda, had already preceded him in illegal activities, as he was a renowned whiskey smuggler at a time when it was illegal (early 20th century).[39][40] Gaviria Cobaleda was also the grandfather of the Colombian lawyer and politician José Obdulio Gaviria.[41]

"Well, my family did not have significant financial resources and we lived through difficulties like those experienced by the majority of Colombian people, so we are not oblivious to these problems, we know them deeply and we understand them."

— Pablo Escobar[42]

However, his ancestors and immediate family members stood out as politicians, businessmen, ranchers and figures of the Antioquian elite,[43] therefore, his widely publicized "popular origins" would not correspond to reality. Among his extensive family members is Isabel Gaviria Duque, First Lady of the Nation, wife of Carlos E. Restrepo, who was President of Colombia between 1910 and 1914. Pablo Escobar's godfather was the renowned Colombian diplomat and intellectual Joaquín Vallejo Arbeláez. His death is kept in the parish of Rionegro, which reads:

In the parish of San Nicolás de Rionegro, on December 4, 1949, Father Juan M. Gómez baptized a child who was born on the first day of the present, whom he named PABLO EMILIO, legitimate son of Abel de Jesús Escobar and Hermilda Gaviria, residents of this parish. Paternal grandparents: Pablo Emilio Escobar and Sara María Echeverri. Maternal grandparents: Roberto Gaviria and Inés Berrío. Godparents: Joaquín Vallejo and Nelly Mejía de Vallejo, who were advised of their spiritual relationship and obligations. I attest. Agustín Gómez. Priest. MARGINAL NOTE OF CONFIRMATION. Confirmed in the Minor Basilica by His Excellency Mr. Alfonso Uribe Jaramillo, on October 21, 1952. Godfather: Gustavo Gaviria. I attest. Juan M. Gómez, Priest. MARGINAL NOTE OF MARRIAGE. He was married in Palmira, Valle, parish of La Stma. Trinidad, on March 29, 1976. Witnesses: Alfonso Hurtado and Dolores de Vallejo. He married Victoria E. Henao. I attest to this. Monsignor Samuel Álvarez Botero.

Childhood and youth

According to his mother, Escobar began to show insight and cunning as early as elementary school; and at the beginning of high school, another of his qualities became evident: his leadership over his classmates. Escobar and his cousin Gustavo Gaviria Rivero did small "businesses" at the Lucrecio Jaramillo Vélez high school, where they both studied. They held raffles, exchanged comics, sold exams and lent money at low interest. In this way, Pablo Escobar began to develop his "ability" for business and commerce.

Escobar left high school in 1966 just before his 17th birthday, before returning two years later with his cousin Gustavo Gaviria. At this time, the hard life on the streets of Medellín had polished them into gangster bullies in the eyes of teachers. The two dropped out of school after more than a year, but Escobar did not give up. Having forged a high school diploma, he was admitted to study at the Faculty of Economics of the Latin American Autonomous University of Medellin, where several of his Gaviria cousins were studying, including José Obdulio, with the goal of becoming a criminal lawyer, a politician, and eventually the president but had to give up because of lack of money. Escobar preferred to dedicate himself to his personal "businesses." An interesting fact, he always felt self-conscious about his short stature (1.65 m) and this made him wear special shoes with heels to make himself look taller.[44][45][46][47]

Criminal career

Early

Escobar started his criminal career with his gang by with small scams, thefts, and after stealing tombstones, sandblasting their inscriptions, and reselling them. After dropping out of college, Escobar began to join gangs to steal cars.[48] Escobar soon became involved in violent crime, employing criminals to kidnap people who owed him money and demand ransoms, sometimes tearing up ransom notes even when Escobar had received the ransom. It is speculated that businessman Diego Echavarria Misas was kidnapped and eventually killed in the summer of 1971 with the participation of Escobar, who supposedly received a $50,000 ransom from the Echavarria family.[49][50] Escobar would repeat the same process with drug lord Fabio Restrepo, kidnapping and murdering him in 1975.[51][52]

After Escobar would later begin to work for Alfredo Gómez López, 'Don Capone', the king of smuggling in Colombia.[53] Escobar soon entered the drug trade by smuggling marijuana to the United States under the patronage of Griselda Blanco. After the end of the marijuana boom, Escobar began working as an intermediary who bought cocaine paste in Colombia, Bolivia and Peru, to later resell it to his partners the Ochoa brothers, traffickers in charge of taking it to the United States.

Medellín Cartel

Escobar had been involved in organized crime for a decade when the cocaine trade began to spread in Colombia in the mid-1970s. Escobar's meteoric rise caught the attention of the Colombian Security Service (DAS), who arrested him in May 1976 on his return from drug trafficking in Ecuador. DAS agents found 39 kg of cocaine in the spare tire of Escobar's car. Escobar managed to change the first judge in the lawsuit and the process expired, apparently by bribed the second judge, so he was released along with other prisoners. Despite this, the case was reopened by Judge Mariela Espinosa, who also dropped the investigation due to threats against her life.[55] The following year, the agents who arrested Escobar were assassinated. Escobar continued to bribe and intimidate Colombian law enforcement agencies in the same fashion. His carrot-and-stick strategy of bribing public officials and political candidates in Colombia, in addition to sending hitmen to murder the ones who rejected his bribes, came to be known as "silver or lead", meaning "money or death".[56][46][57] The Medellín Cartel and the Cali Cartel both managed to bribe Colombian politicians, and campaigned for both the Conservative and Liberal parties. Although the difference between the two cartels was that the Medellín Cartel used its "money or death" law through a huge army of hitmen, the Cali Cartel preferred to use bribes by having politicians, journalists, police officers, army officers, judges, etc. on its payroll.[58][59] Hence, Escobar and many other Colombian drug lords were pulling strings in every level of the Colombian government because many of the political candidates whom they backed financially were eventually elected.[58] Although the Medellín Cartel was only established in the early 1970s, it expanded after Escobar met several drug lords on a farm in April 1978, and by the end of 1978 they had transported some 19,000 kilograms of cocaine to the United States.[60]

Rise to prominence

Soon, the demand for cocaine greatly increased in the United States, which led to Escobar organizing more smuggling shipments, routes, and distribution networks in South Florida, California, Puerto Rico, and other parts of the country. He and cartel co-founder Carlos Lehder worked together to develop a new trans-shipment point in the Bahamas, an island called Norman's Cay about 350 km (220 mi) southeast of the Florida coast. Escobar and Robert Vesco purchased most of the land on the island, which included a 1-kilometre (3,300 ft) airstrip, a harbor, a hotel, houses, boats, and aircraft, and they built a refrigerated warehouse to store the cocaine. According to his brother, Escobar did not purchase Norman's Cay; it was instead a sole venture of Lehder's. From 1978 to 1982, this was used as a central smuggling route for the Medellín Cartel. With the enormous profits generated by this route, Escobar was soon able to purchase 20 square kilometres (7.7 sq mi) of land in Antioquia for several million dollars, on which he built the Hacienda Nápoles. The luxury house he created contained a zoo, with more than two hundred species of exotic animals for the region, such as hippos, giraffes, elephants, zebras and ostriches, all introduced into the country as a result of bribes to the government entity INDERENA and the customs authorities; a lake, a sculpture garden; a private bullring; and other amenities for his family and the cartel. Escobar made a show of this by producing a propaganda report about his Hacienda.[61]

Escobar was also among the world's billionaires due to his immense fortune invested in buildings, homes, automobiles and estates. listed as the seventh richest man in the world, according to Forbes, something his son would deny years later.[62][63]

Escobar's political career

At the height of his power, Escobar was involved in philanthropy in Colombia and paid handsomely for the staff of his cocaine lab. Escobar spent millions developing some of Medellín's poorest neighborhoods. He built housing complexes, parks, football stadiums, hospitals, schools, and churches.[65][66] His most famous charity work was the 'Medellín without slums' neighbourhood, aimed at people living in slums at the Medellín municipal dump.[67][68] Shortly before the presidential and regional elections of 1982 began, Escobar realized that he had to create a "cover" to protect his lucrative drug trade. He began to cultivate an image of a respectable man, making contacts with politicians, financiers, lawyers, etc. Considered until then a 'Robin Hood paisa' due to his help to the poor of Medellín, Escobar would enter politics with the help of Jairo Ortega Ramírez as a congressman representing Antioquia through the Liberal Renewal movement,[69][70] although his godfather in politics was the liberal chieftain from Tolima Department Alberto Santofimio Botero. This triumvirate initially supported the candidacy of Luis Carlos Galán, a dissident of the Liberal Party for his New Liberalism movement. While campaigning politically in Medellín, Galán learned through his assistant Iván Marulanda that people whose fortunes were of dubious origin had joined the Liberal Renovation movement. In Medellín's Berrío Park, Galán, without mentioning Escobar's name, publicly expelled him, rejecting the support of Escobar and others similar to him involved in shady business dealings.[71][72] Despite the opposition and warnings of his partners, in 1982, he successfully entered the Colombian Congress. Although only an alternate, he was automatically granted parliamentary immunity and the right to a diplomatic passport under Colombian law. At the same time, Escobar was gradually becoming a public figure, and because of his charitable work, he was known as "Robin Hood Paisa". He alleged once in an interview that his fortune came from a bicycle rental company he founded when he was 16 years old.[73]

After of his election, Escobar was invited in 1982 to the inauguration of Felipe González, the third president of democratic Spain, by the Spanish businessman Enrique Sarasola, who had important business dealings in Medellín.[74][75][76][77][78][79]

In Congress, in 1983, the new Minister of Justice, Rodrigo Lara-Bonilla, had become Escobar's opponent, accusing Escobar of criminal activity from the first day of Congress. Lara, who had since denounced the infiltration of illicit money into Colombian politics and soccer teams,[80][81] accused him not only of being a drug trafficker but also of being the leader of the paramilitary group Death to Kidnappers (MAS), created in 1981 to violently stop the onslaught of the M-19 guerrilla movement that had kidnapped Martha Nieves Ochoa, sister of his associates, and an attempted kidnapping of his partner Carlos Lehder who managed to escape wounded in the leg.[82][83] Escobar secretly counterattacks alongside Jairo Ortega by showing a copy of a check from drug trafficker Evaristo Porras to Lara's Senate campaign,[84][85][86] in addition to challenging the minister to show evidence against him under penalty of being sued for slander and defamation. Guillermo Cano, editor and owner of the newspaper El Espectador, seeing Escobar, sensed that he knew him from somewhere, so accompanied by María Jimena Duzán and another reporter, they went to the disorganized archive of the newspaper and found the headline in which it was reported that Escobar together his cousin Gustavo Gaviria had been arrested for possessing coca paste.[87]

Escobar's arrest in 1976 was investigated by Lara-Bonilla's subordinates, this confirmed in a Brian Ross's September 5, 1983 report, on the U.S. television network NBC.[88] A few months later, Escobar was publicly expelled from Congress and his visa to the United States was cancelled, while Judge Gustavo Zuluaga Serna issued an arrest warrant against Escobar for the murder of the two DAS agents who had captured him in 1976. At the same time, and with Lara's approval, the police, headed by Colonel Jaime Ramírez, together with the DEA discovered and dismantled Tranquilandia, a complex of several cocaine processing laboratories owned by Rodríguez Gacha. Although Escobar fought back, he announced his retirement from politics in January 1984.[89][90] Three months later, Lara-Bonilla, whose honor had previously been called into question and then vindicated, was murdered.[91][92][93]

War against drugs and narcoterrorism

Colombia will hand over criminals requested by the Crime Commission in other countries; so that they are punished in an exemplary manner, in this universal operation against an attack that is also universal.

President Belisario Betancur, who had previously opposed the extradition of Colombians, decided to authorize it, triggering a series of police operations to capture members of the Medellín Cartel. The main leaders of the Cartel had to take refuge in Panama and tried, in May 1984, to talk with former President Alfonso López Michelsen, who was acting as an electoral observer in the elections in Panama, at the Hilton Hotel in Panama City in a last attempt to approach the government, denying their authorship of the murder of the minister but offering to surrender on condition of not extraditing them. Their failure was due to the fact that the talks had been leaked to the press. Months later, they returned clandestinely to Colombia.[96][97][98]

In November 1984, Los Extraditables detonated a car bomb in front of the US embassy in Bogotá, killing one person.[99] A year after the murder of Lara Bonilla, despite the government's announcements to combat them, the drug traffickers of the Medellín Cartel, now renamed Los Extraditables, remained unpunished, expanding their criminal apparatus across large areas of the country and opening new cocaine trafficking routes through Nicaragua and Cuba. All of this in collusion with some sectors of the public forces, bought off with money and terror. In the fall of 1985, the wanted Escobar requested the Colombian government to allow his conditional surrender without extradition to the United States. The proposal was initially rejected, The Los Extraditable Organization was subsequently accused of participating in an effort to prevent the Colombian Supreme Court from studying the constitutionality of Colombia's extradition treaty with the United States.[100][101]

The Colombian judiciary had been a target of Escobar throughout the mid-1980s. While bribing and murdering several judges; beginning in June 1985, Los Extraditables ordered the death of Judge Tulio Manuel Castro Gil, in charge of investigating the Lara Bonilla murder.[102][103][104][105][89] According to reports, Escobar, who was at war with the guerrillas after the MAS episode, approached the M-19 through negotiations with Iván Marino Ospina. According to some reports, it is believed that he was aware of the Palace of Justice siege due to the threats made by Los Extraditables to the magistrates of the courts and because he offered economic support for the operation, which was not accepted by the former M-19 militants, since the operation, according to them, had political objectives.[106] The existence of copies of the files and the extradition requests in the foreign ministry, American courts and the American embassy disproves that the burning of files was the reason for the guerrilla operation.[107] The operation was authorized by Álvaro Fayad and took place between November 6 and 7, 1985, resulting in 94 dead and the disappearance of 11 people during the retaking of the Palace by the Public Force.[108]

The Cartel's campaign of assassinations against its enemies in the Government and those who supported the extradition treaty, made effective in January 1985 with the sending of the first captured to the United States[109] by the newly appointed Minister of Justice Enrique Parejo González, replacing the murdered Lara, and all those who denounced their business and mafia networks. The Extraditables assassinated, in February 1986, in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, the pilot and witness before the American justice system Barry Seal;[110][111][112] in July, the magistrate Hernando Baquero Borda, rapporteur of the Extradition Treaty in 1980,[113][114][115] and the journalist of El Espectador Roberto Camacho Prada;[116] and on August 18, already with the new president of Colombia Virgilio Barco Vargas, the captain of the anti-narcotics police Luis Alfredo Macana.[117][118]

In September 1986, Los Extraditables ordered the murder of Diario Occidente journalist Raúl Echavarría Barrientos.[119][120][121][98] In September 1986, motorized hitmen killed Judge Zuluaga Serna.[89][122][123]

In October 1986, anti-narcotics police colonel Jaime Ramírez Gómez was killed after returning to Bogotá from a weekend trip with his family.[124][125][126] On December 17, 1986, Guillermo Cano, editor of El Espectador newspaper, was killed.[127][128][129][130] In January 1987, Escobar's hitmen attacked Parejo González, former Minister of Justice in Budapest and at the time Colombian ambassador to Hungary.[131][132][133][134][135][136][137]

In late 1986, Colombia's Supreme Court declared the previous extradition treaty illegal due to being signed by a presidential delegation, not the president. Escobar's victory over the judiciary was short-lived.[138][139] It is believed that Escobar was the one who betrayed Lehder, causing his capture on February 4, 1987. However, unexpectedly, Lehder was extradited to the United States.Escobar and the rest of the leadership, aware of the danger that extradition represented for their interests and determined to fight it, reinforced their military and economic apparatus and set about collecting considerable resources from all drug traffickers, even from those who were not part of their group, in order to finance the foreseeable escalation of violence.[140][141][142][143]

War between drug cartels

Although both cartels maintained a cordial relationship, the origin of the war between the Medellin and Cali cartels has varied origins. One version suggests disagreement with the violent methods used by Escobar. Added to this, the Cali Cartel opposed a "war quota" against the government by refusing to pay for it. Another version suggests the Cali Cartel's zeal to take control of the drug market in Los Angeles and Miami since it currently monopolized drug trafficking in New York City, according to a DEA analysis.[144] another version suggests that the Cali Cartel informed on Jorge Luis Ochoa, Escobar's partner, while Ochoa was in Buga, Valle del Cauca. This has been denied since Ochoa and Gilberto Rodríguez Orejuela had shared a cell in Spain where they were to be extradited to the United States, but both were repatriated to Colombia where they served ridiculous prison sentences.[145][146][147][148][149] According to Jhon Jairo Velásquez 'Popeye', a hitman for the Medellín Cartel, the dispute between the two sides began due to disputes between employees of Pablo Escobar and Hélmer Herrera:

The war began with a love affair between "Piña" and Jorge Elí "El Negro" Pabón. "El Negro" Pabón was a man very loyal to Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria and Alejo Piña was a man of "Pacho" Herrera, both had been friends in a New York prison, but when El Negro got out of prison, he found out that Piña was living with his former wife, El Negro spoke with the boss [Escobar] and they agreed that Piña had to be killed; As the Medellín Cartel killed Hugo Hernán Valencia, a man who had had a problem with Gilberto Rodríguez, we asked the Rodríguez family to return the favor, to let us kill Piña or for them to take care of him themselves, with their people. We did not know about the economic and military power of "Pacho" Herrera. The Rodríguez family, instead of explaining this to their boss, went directly to tell 'Pacho' Herrera that the Medellín Cartel wanted to kill Piña, and that's when war broke out.

— Jhon Jairo Velásquez 'Popeye'[150]

Hugo Hernán Valencia and Pablo Correa Arroyave were the main money launderers for the Cartel. Both had a feud with the heads of the Cali Cartel and the latter had asked Escobar to do them a favor by killing them. But when the Cali Cartel refused to kill Piña, Escobar allowed Pabón to kill Piña. In retaliation, on January 13, 1988, 'Pacho' Herrera ordered his men to place a car bomb at the Monaco tower in the El Poblado sector of Medellín, where Escobar's family resided.[151][152] The attack left a large crater and killed three people. Among the wounded was Manuela Escobar, Escobar's daughter, who had hearing damage in one of her ears. None of the residents were killed.[153][154][155][156][157][158] In retaliation, hitmen from the Medellin Cartel attacked the businesses and properties of the Cali Cartel. On February 18, 1988, a branch of La Rebaja Pharmacies in Medellin,[159][160][161] followed by nearly 40 dynamite attacks against the drugstores, and 10 more against the Colombian Radio Group, both belonging to the Rodríguez Orejuela family.[162][22][163][164] 1988 marked the beginning of espionage and counterespionage offensives. First, Escobar set up an intelligence operation against the Cali Cartel. The Rodríguez Orejuela family, in turn, hired five retired military officers to form an espionage service against Escobar. Escobar discovered them and kidnapped them. The Cali Cartel then made a peace proposal, to which Escobar set two conditions: Compensation of 5 million dollars for the attack on the Monaco building, and the surrender of Pacho Herrera, Escobar's staunch enemy. Gilberto Rodríguez refused to surrender and the five ex-military men were found dead a few days later with a sign that read "Members of the Cali Cartel executed for attempting to attack people from Medellín."[165]

In December 1988, Escobar's hitmen attempt to kidnap Pacho Herrera in Cali, the operation fails and Herrera becomes Escobar's main target.[23]

1989 offensive and failed negotiations

Minister of Justice Enrique Low Murtra signed the extradition orders for Escobar and his cartel associates.[166] A few days later, the politician and candidate for mayor of Medellín, Juan Gómez Martínez,[167][168] was saved from an attempted kidnapping claimed by Los Extraditables, while Jorge Luis Ochoa was released with impunity under the right of habeas corpus a month later.

On January 16, 1988, Escobar's hitmen kidnapped Andrés Pastrana (candidate for mayor of Bogotá and later President of Colombia) and held him hidden for several days on a farm near Rionegro.[169][170][171][172][173] On January 25, 1988, cartel hitmen kidnapped Carlos Mauro Hoyos (Attorney General of the Nation), as he was heading to the airport in Rionegro (Antioquia). Although the plan was to keep both Hoyos and Pastrana captive in the same place, the money lavishness of Jorge Restrepo, the front man in charge of Pastrana who was held captive (barely a week) caught the attention of the authorities and the police managed to free Pastrana. But in retaliation, alias 'Popeye' shot and killed Carlos Mauro Hoyos (48), who had been kidnapped for 10 hours.[174][175][176] In March 1988, several hundred police officers descended on the El Bizcocho estate (owned by Escobar), but he was warned at the last minute by the corrupt Lieutenant Colonel Plinio Correa of Police Intelligence B-2 and managed to escape.[177][178][179][180]

In July 1988, the Secretary General of the Presidency, Germán Montoya, had entered into talks with spokesmen for Los Extraditables. Subsequent statements by the government were interpreted by the drug lords as an invitation to dialogue, so on September 15, they responded with a letter to the Barco administration, and sent Montoya a bill for pardons and a demobilization plan. However, given the intransigence of the United States, reluctant to the possibility of dialogue with the drug lords, the talks were delayed and in the end they were presented as the personal initiative of the intermediary, disassociating the president from them.[181]

In March 1989, hitmen from Los Extraditables killed Héctor Giraldo Gálvez,[182][183] the Lara case manager replacing Castro Gil, and two months later they blew up the headquarters of the TV production company Mundo Visión.[184] On May 4, 1989, the former governor of Boyacá, Álvaro González Santana, father of Judge Martha Lucía González, was assassinated.[185][186] After the attempted assassination of the head of the DAS, General Miguel Maza Márquez on May 30, 1989, in Bogotá, using a powerful explosive charge in a letter bomb that killed 7 people.[187] On July 4, 1989, in Medellín, in an attack targeting Colonel Valdemar Franklin Quintero, the governor of Antioquia, Antonio Roldán Betancur, died along with five of his companions.[188][189][190] On July 28, 1989, Escobar's hitmen murdered Judge María Helena Díaz – Espinoza's substitute in the Escobar and Gaviria case for possession of coca paste – and her two bodyguards.[191][192][193][194]

On August 16, 1989, Escobar's hitmen killed the judge of the superior court of Cundinamarca, Carlos Ernesto Valencia,[195][196] and on August 18 in Medellin, Colonel Quintero was shot dead by dozens of bullets. Although the news of the crime that occurred in the morning hours was overshadowed, when at night during a political rally in Soacha, Escobar still held a grudge against Luis Carlos Galán for kicking him out of politics, so Galán was assassinated on 18 August 1989 at Escobar's orders; several dozen gunmen in the service of Rodríguez Gacha infiltrated the demonstration and killed the presidential candidate for the Liberal Party, Luis Carlos Galán, a staunch enemy of drug lords and supporter of allowing the extradition of drug lords to the US, who had the best chance of reaching the presidency of the nation. Also involved in this murder was the politician Alberto Santofimio Botero, who in 2006 was shown to have been the intellectual co-author of the crime.[98][197]

President Barco declared war on drug trafficking in the same way that Betancur had done five years earlier. With Decree 1830 of August 19, 1989,[198] Barco established extradition by administrative means, without taking into account the ruling of the Supreme Court of Justice; with Decree 1863[199] he authorized military judges to conduct searches where there were suspicions or indications of persons or objects related to a crime; with Decree 1856 he ordered the confiscation of all movable and immovable property of drug traffickers;[199][200][201] and with Decree 1859[199] he authorized the capture was authorized in conditions of absolute incommunication detention and for a time that exceeded constitutional norms, of persons of whom there were serious indications of having committed crimes against the existence and security of the State. In addition, the creation of the Elite Group of the police with 500 men was arranged, essentially aimed at hunting down terrorist leaders, and it was placed under the command of Colonel Hugo Martínez Poveda. In the following days, the Army and the Police carried out more than 450 raids throughout the country and arrested nearly 13,000 people accused of being linked to drug trafficking.

On August 23, the Extraditables responded to the government in a letter to the public, taking on the challenge of total war. With 3,000 armed hitmen, the association of paramilitarism and the support of a significant portion of the population under its control, in addition to the financial muscle that gave it control of at least 90% of cocaine trafficking abroad, the Medellín Cartel confronted the Colombian state with bombings and selective assassinations. Terrorism multiplied and put the government in check: between September and December 1989, more than 100 devices exploded in Bogotá, Medellín, Cali, Bucaramanga, Cartagena, Barranquilla and Pereira, against government buildings, banking, commercial and service facilities and economic infrastructure. In those three months, including the hitmen, the narco-terrorists were responsible for 289 terrorist attacks in that period, with a fateful balance of 300 civilians killed and more than 1,500 wounded.[202] On November 1, 1989, Judge Mariela Espinosa was murdered on Escobar's orders.[203][204][205][206][207][208]

On November 23, 1989, a lightning operation was launched against the El Oro ranch in Cocorná (Antioquia), where Pablo Escobar and Jorge Luis Ochoa were staying. Escobar and Ochoa managed to escape, but two of his men were killed – one of them his brother-in-law, Fabio Henao – and 55 were arrested.[209][210] Four days later, on November 27, Escobar then planted a bomb on Avianca Flight 203 in an attempt to assassinate Galán's successor, César Gaviria Trujillo, had not boarded the plane on the advice of his security advisers and survived. All 107 people were killed in the blast. Because two Americans were also killed in the bombing, the U.S. government began to intervene directly.[211][212][213] On December 6, 1989, Escobar's hitmen placed a bus bomb in front of the building of the DAS – the Colombian secret police – in an attempt to assassinate its director, General Miguel Alfredo Maza Márquez, who emerged unharmed despite the building being half-destroyed. The bus bomb also destroyed more than 200 commercial establishments around it. 63 civilians were killed and 500 were injured.[214][215][216]

Wave of kidnappings and failed negotiations

On December 15, 1989, Barco's government managed to kill the second leader of the Medellín cartel and its military leader, El Mexicano (Rodríguez Gacha). He was located by an informant working for the Cali Cartel on the northern coast of the country, where he was seeking refuge from the authorities' persecution. Responsible for more than 2,000 homicides and claiming responsibility for the attack on the DAS tower, he was killed after a tough chase between the municipalities of Tolú and Coveñas in the Sucre Department, along with his son Freddy Rodríguez Celades, his main lieutenant Gilberto Rendón Hurtado and four hitmen from his security force. Most of the terrorist attacks of the last few months were attributed to 'El Mexicano'.[217][218]

Although the Medellín Cartel and the government had made a series of approaches to reach negotiations that would lead to the surrender of the drug lords, the intransigence of the US justice system and the recent acts of violence prevented any such option. The Extraditables attempted a new strategy of dialogue and negotiation with the State, wanting to pressure it with the kidnapping of the son of the Secretary of the Presidency, Álvaro Diego Montoya, and two relatives of the President of the Republic, in addition to other personalities. A proposal then arose from former President López Michelsen, supported by former Presidents Julio César Turbay and Misael Pastrana, by Cardinal Mario Rebollo Bravo and by the President of the UP Diego Montaña Cuellar, consisting of the formation of a commission of Notables to negotiate with the narcoterrorists.[219] On January 17, 1990, they responded to the government's proposal, presenting themselves in a statement as legitimate candidates for judicial pardon and expressing a "genuine willingness to negotiate." Immediately afterward, they released the hostages, handed over a bus with a ton of dynamite, and one of the largest drug processing laboratories in Chocó. All process that began after a statement in which Los Extraditables described the declaration of the former presidents and the leader of the UP as a "patriotic invitation," while declaring that they recognized the "victory of the State." In return, the drug traffickers expected the government to create a high-level commission that would be in charge of the legal procedures that would allow their surrender. The government considered names to lead the process and the most likely candidate was Otto Morales Benítez, former government negotiator with the guerrillas.[220] However, the approaches were leaked to the press and the attempt at dialogue and negotiation ended in a new wave of terrorism, and announced that, on the contrary, it would strengthen the extradition process. This did not prevent the complete release of the hostages before the end of January 1990. On January 22, Álvaro Montoya was released near the main entrance of the National University of Colombia, without the sign requiring him to convey any message to the public.[221]

The Extraditables, effectively deceived by the Government and faced with a strong military offensive in Envigado, declared a zone of military operations by the IV Brigade under the command of General Harold Bedoya, the Extraditables ended the truce on March 30, putting a price on the head of each policeman killed. Medellín and its metropolitan area were involved in an urban war, after the first executions of uniformed officers and after the attack against a truck of the Elite Group, which occurred on a bridge in Itagüí on April 11. This attack, which left 20 dead and 100 wounded, was the first of 18 that occurred until the end of July with a balance of 100 fatalities and 450 wounded.[20]

The 1990 presidential elections were marked by constant violence in which not only Galán was killed, but also Bernardo Jaramillo Ossa, of the leftist UP party; and Carlos Pizarro, leader of the dissolved M-19 guerrilla movement. Although the government blamed Escobar for the murders of Jaramillo[222] and Pizarro,[223] they were actually committed by paramilitaries under the command of his allies Fidel and Carlos Castaño Gil. Gradually the cordial relations between the paramilitaries and Los Extraditables would deteriorate because of this.

On May 12, the eve of Mother's Day, bombs exploded in two commercial districts in Bogotá, killing twenty-one people. On the same day in Cali, another terrorist act claimed the lives of nine civilians. At the end of the month, at the same time that a hitman blew himself up in front of the Intercontinental Hotel in Medellín,[224][225] killing six policemen and three passers-by, Senator Federico Estrada Vélez and his driver were gunned down.[226][227] The violence intensified and the victims were thousands: in retaliation for the death of 215 policemen killed between April and July 1990, death squads went up to the communes every night and shot dozens of men, several of children and/or adolescents.

Shortly after Escobar's military chief, Pinina (John Jairo Arias Tascón), was assassinated on June 14,[228][229][230] another series of military actions followed: nineteen young people from Antioquia's high society were killed in the Oporto Bar Massacre[231][232][233][234][235][236] and a car bomb exploded in front of the Libertadores Police Station, killing fourteen civilians. Finally, at the end of July, after a huge operation in Antioquia's Magdalena Medio from which Escobar once again escaped, Los Extraditables declared a new truce and went on the defensive, awaiting the decisions that the incoming Gaviria government might take. In any case, they affirmed the impossibility of surrendering to justice until the State security agencies are restructured and the appropriate legal mechanisms are created to avoid their extradition.[98]

Furthermore, the cartel war did not cease. On June 22, 1989, the Cali Cartel, through its head of security, Jorge Salcedo, hired a group of British mercenaries led by Peter McAleese and sent them to Hacienda Nápoles to attack Escobar, but the operation failed because the helicopter carrying the mercenaries crashed due to overloading.[237]

In November 1989, after the Colombian Professional Football match between Independiente Medellín and América de Cali, referee Álvaro Ortega was murdered on Escobar's orders due to illegal betting with the Cali Cartel according to Popeye and Fernando Rodríguez Mondragón.[238][239][240]

On September 25, 1990, taking advantage of the fact that Pacho Herrera was going to attend a private soccer game on one of his farms in a district of Candelaria (Valle del Cauca), several hitmen dressed in uniforms of the National Army entered the place and carried out the Los Cocos Hacienda Massacre. They opened fire, leaving 18 people dead; however, Pacho Herrera was unharmed and escaped. The attack was ordered by Escobar, who would command a new assault against Herrera on July 27, 1991, at a beach resort located on the highway leading from Cali to Jamundí.[241][242][243][244]

New kidnappings and attacks

Apart from an unfinished peace process, President César Gaviria inherited the "war on drugs" with which his predecessor had sought to reduce the Medellín Cartel and its network of hitmen, declared enemies of the State.[245] Although during his presidential campaign he had shown total support for both the offensive and the measures taken by Barco, including the most feared by narco-terrorists; which was extradition by administrative means; once in office he hinted that the high economic and human cost of this war deserved the search for an alternative solution in which the strengthening of justice would be a key element. On August 12, in any case, in a coup, men from the Elite Group of the police killed Gustavo Gaviria Rivero, Escobar's cousin and right-hand man.[246][247]

Taking advantage of the respite from the unilateral, indefinite truce announced in July by Los Extraditables, Justice Minister Jaime Giraldo Ángel designed the state of siege legislation that would be made public as a "policy of submission to justice."[248][249] This policy, which materialized in five decrees that would later,[250] after a purge, be elevated to permanent legislation in the new Code of Criminal Procedure, aspired in simplified terms to favor, by reducing the sentence of drug traffickers who voluntarily surrendered and confessed to at least one crime, with the guarantee, in some cases conditional, of being tried in the country and held in high-security prisons. The first to accept the offer, between December 1990 and February 1991, were the Ochoa brothers, Jorge Luis, Juan David and Fabio,[251][252] close associates of Escobar, who, suspicious of the intentions of the Government, which had already failed to comply with him previously, organized a series of selective kidnappings of renowned journalists and influential figures in national life.

Escobar ordered the kidnapping of relatives of members of the Government and journalists. From the long list of those kidnapped, the most well-known were: Francisco Santos Calderón (editor-in-chief of the newspaper El Tiempo),[253] Maruja Pachón de Villamizar (journalist and general director of FOCINE, wife of the politician and diplomat Alberto Villamizar),[254] Beatriz Villamizar de Guerrero (sister of Alberto Villamizar and personal assistant of FOCINE), Diana Turbay (director of the television news program Criptón and of the magazine Hoy x Hoy, daughter of the former president of the republic Julio César Turbay) with her journalistic team from Criptón, Marina Montoya de Pérez (sister of the former general secretary of the Presidency Germán Montoya) and who was executed by her captors in retaliation for the failure of the rapprochements with the government at the end of 1989, for the death of hitmen and collaborators of the Cartel at the hands of the police, especially for the death of the brothers Armando and Ricardo Prisco Lopera, leaders of Los Priscos, the armed wing of the cartel, Patricia Echeverri and her daughter Diana Echeverri, political relatives of the former president of the republic Barco, thus putting pressure on the outgoing president and the elected Gaviria to be treated as a political criminal, thus becoming a beneficiary of the pardons reserved for the guerrillas. Escobar also intended to force the Executive to make an agreement tailored to his needs and continued to apply pressure again through armed means, threatening to execute the hostages and to restart his terrorist offensive.[255]

On December 13, 1990, a bomb killed 7 police officers in Medellín and another 7 were killed by hitmen in the first 3 days of January and with a new wave of attacks: a dozen police officers were victims of contract killings, an explosion on a bus left 6 dead and on February 16, a heinous bomb attack against a secret police F2 patrol in Medellín in front of the city's bullring resulted in 22 civilian deaths. Two months later, Escobar's hitmen killed the former Minister of Justice Enrique Low Murtra in Bogotá.[256][257][258][259][260][excessive citations]

Although most of the hostages had been released, not only as a gesture of good faith but also because of the apparent success of negotiations to avoid Escobar's extradition, on January 25, 1991, Diana Turbay fell dead in the arms of her cameraman Richard Becerra in the middle of a shootout during an apparent rescue operation. Turbay's death infuriated Escobar since the journalist was his best card to negotiate his non-extradition to the USA.[261][262][263][264][265][266][267][268][269][270][271][272][273][274][275][excessive citations]

Surrender and submission to justice

Turbay's death motivated the families of the other hostages to seek their release on their own. With only Francisco Santos, Beatriz Villamizar and Maruja Pachón remaining kidnapped, Villamizar was released on February 6, 1991, thanks to the efforts of her husband, Congressman Luis Guerrero. At the same time, the Eudist priest Rafael García-Herreros who had been contacted by an emissary of Escobar, under his orders, saying that he was tired of his war and trusted him for an eventual surrender. On his daily TV show 'El Minuto de Dios', García-Herreros had expressed Escobar's apparent interest in surrendering, but at the same time his doubts.[276]

«Oh, sea of Coveñas! Oh, immense sea! Oh, lonely sea, that knows everything! I want to ask you some things, answer me. You who keep the secrets, I would like to build a great rehabilitation institute for hitmen in Medellín. Talk to me, you who keep the secrets, I would like to talk to Pablo Escobar, on the seashore, right here, the two of us sitting on this beach... They have told me that he wants to surrender, They have told me that he wants to talk to me. Oh, sea! Oh, sea of Coveñas at five in the afternoon, when the sun is setting! What should I do? They tell me that he is tired of his life and his struggle, and I cannot tell anyone, my secret. However, it is drowning me inside... Oh, sea! My God; in your hands we place this day that has already passed and the night that is coming.»

— Priest Rafael García-Herreros, April 19, 1991[277]

García-Herreros traveled to Medellín to meet with Fabio Ochoa Restrepo, patriarch of the Ochoa family, and Ochoa took the priest to the Itagüi prison to introduce him to his sons, imprisoned for surrendering to the 'Policy of Submission to Justice'. Through the Ochoa family, García-Herreros sent a letter to Escobar and Escobar responded with another 4-page letter; in this letter he showed his confidence in the priest but demanded several conditions from the Government for surrender. One of them was that the members of the Elite Corps of the police who had killed his cousin Gustavo Gaviria for violating Human Rights be punished, to which President César Gaviria and his advisor for Security, Rafael Pardo, did not respond to the requests. Days after receiving the message, García-Herreros was summoned to Fabio Ochoa's ranch, where he waited for Escobar's call. Escobar reiterated his desire to surrender but on the condition that he would not be held in the Itagüi prison for fear of being killed, and that the hostages would soon be released. Escobar also clarified that he had not ordered the murders of leftist candidates Jaime Pardo Leal, Bernardo Jaramillo and Carlos Pizarro.[278]

However, Pachón and Santos remained kidnapped for a few more months due to Escobar's distrust of the government, and their release was personally facilitated by Enrique Santos, Santos' father, and Alberto Villamizar, Pachón's husband, with government authorization. García-Herreros was also a mediator not only for the release of Pachón, finally achieved on May 21, 1991, but also for that of Santos a day later, on May 22 of that same year.[279][280][281][254][282][283][276][excessive citations]

Eventually, the government negotiated with Escobar and convinced him to surrender and cease all criminal activity in exchange for a reduced sentence and preferential treatment during his captivity. Although Escobar's eventual surrender had been brewing since November 1990, Escobar, in the midst of his negotiations, managed to obtain permission to build his own prison. For that purpose, and with the collaboration of the mayor of Envigado, Jota Mario Rodríguez, the government was offered a three-hectare plot of land, located in the area of 'La Catedral', where the Claret, a rehabilitation center for drug addicts, was being built. The then Vice Minister of Justice, Francisco Albeiro Zapata, visited the construction site and gave his approval. However, what was unknown was that the property had been purchased by Escobar. In May, more than 60 workers worked on more than 1,800 square meters to build the La Catedral prison. The contract had a rather clause: "No police or military authority will have access to the internal part of the prison."[284] The surrender was to take place on May 18, 1991, but two events prevented it: the origin of the designated director of the cathedral, Jorge Pataquiva, from Girardot, and of his guards, all from Cundinamarca. Escobar wanted all his guards to be from Antioquia. And second, the speech given on May 7 by the priest García Herreros in "El minuto de Dios" (God's Minute): a sermon in which he would not speak of Escobar or the surrender and continued to speak of God and the evil of pornography, but Escobar believed that it was a scolding for him, thinking that he had branded him a "pornography reader."[285] The next day García-Herreros met at La Loma, one of Fabio Ochoa's estates. He clarified that it was due to an editing error in the program and apologized to Escobar, who accepted his apologies but asked that they be made public.[286]

The surrender process was resumed. First, 'Popeye' and Luis Carlos Aguilar 'El Mugre' (the filth) surrendered in the second week of June 1991 to be held in La Catedral prison. Later, on June 19, 1991, the day agreed upon for Escobar's surrender, Villamizar, García-Herreros and Luis Alirio Calle, a journalist admired by Escobar and with whom he maintained communication as a third (unofficial) mediator in his surrender, met at the offices of Criminal Investigation in Medellín. The three of them left in helicopters; Villamizar and García-Herreros in one, and Calle in the other with a smuggled recorder so he could record any important conversations, due to Escobar's demand that they not bring cameras or similar equipment to document his surrender. The helicopters arrived at a farm hidden in the middle of a jungle where Escobar boarded the helicopter where the priest and Villamizar were, and the rest of his men in the other helicopter. Both helicopters departed towards La Catedral where, upon arrival, Escobar surrendered his Sig Sauer pistol to Pataquiva and explored the prison shortly before making his surrender official.[287] Declaring an end to a series of previous violent acts meant to pressure authorities and public opinion, Escobar surrendered to Colombian authorities in 1991. At the same time of his surrender, on the way to prison, the extradition of Colombian citizens to the United States had been prohibited by the newly approved Colombian Constitution of 1991. This act was controversial, as it was suspected that Escobar and other drug lords had influenced members of the Constituent Assembly in passing the law.[285] Escobar greeted his mother and wife, whom he had not seen in months. He had a short interview with Calle and was finally imprisoned that same night.[285][288]

As a consequence of the policy of peace and strengthening of justice of the President and his cabinet, I have decided to submit to decrees 2047[289][290][291] and 2147,[292][293] 2372[294][295] and 3030 of 1990 and 303 of 1991,[296][297] supported by the Attorney General of the Nation, by the honorable judges of the Supreme Court of Justice and by the vast majority of the people of Colombia...With my presentation and my submission to justice, I also wish to pay tribute to my parents, to my irreplaceable and incomparable wife, to my pacifist son of 14 years, to my toothless dancer of 7 years and to all my family whom I love so much. In these historic moments of the surrender of weapons by the guerrillas and the pacification of the country, I could not remain indifferent to the yearnings for peace of the vast majority of the people of Colombia. Pablo Escobar Gaviria. Envigado, Colombia, June 19, 1991.

— Escobar's Declaration from La Catedral. June 19, 1991.[298]

La Catedral prison

Between June 1991 and July 1992, Colombia experienced a period of relative peace, except for the government's war against the guerrillas, but such peace was superficial. It is said that shortly before his surrender, Escobar had met with his remaining associates Gerardo Moncada and Federico 'Kiko' Galeano, the Castaño Gil brothers and other mid- and low-level gangsters. Escobar, at that meeting, reaffirmed himself as the leader of the Medellin Cartel, and proclaimed himself the creator of the drug trafficking business, which is why he demanded that he be paid high sums of money for each shipment of drugs to the United States; going from being a drug lord to being an extortionist. According to 'Popeye', the apparent surrender at La Catedral would be nothing more than a vacation due to the war that Escobar was waging against the government. Escobar was confined in La Catedral with his older brother Roberto and several of his men; Otoniel González 'Otto', Carlos Aguilar 'Mugre' (The filth), John Jairo Velásquez 'Popeye', Valentín Taborda, Gustavo González 'Tavo', Jorge Eduardo Avendaño 'Tato' y Johnny Rivera 'El Palomo' (The pidgeon), José Fernando Ospina 'El Mago' (The Wizard), John Jairo Betancur 'Icopor' (Polystyrene), Carlos Díaz 'La Garra' (The Claw) y Alfonso León Puerta 'El Angelito'. Except for a few who still had influence in Medellín; Mario Castaño 'Chopo', Brances Muñoz 'Tyson' and John Jairo Posada 'Titi'; as well as his partners Moncada and Galeano who were in charge of shipping the cocaine.[299]

The Israeli firms that were supposed to finish building the prison never completed their work because they were paralyzed by Escobar's payroll in Medellín.[300] Meanwhile, double-bottomed trucks entered La Catedral transporting money, weapons and even people. La Catedral gradually went from being a 'maximum security prison' to a 'maximum comfort prison'; La Catedral, which featured a football pitch, a giant dollhouse, a luxurious living room designed by his wife Victoria Eugenia, a bar, a Jacuzzi, and a waterfall. Also a strong security provided by the Colombian Army outside, restricted airspace and the penitentiary authorities designated by the state to guard his confinement, although the majority actually were Escobar's hitmen in prison guard uniforms.[301][302][299] Escobar also organised soccer games with Colombian national football team players at La Catedral.[303][304] He also had orgies with beauty queens and models, which at one point angered his wife.[305]

Escobar's luxuries were discovered by Attorney General Carlos Gustavo Arrieta, who raised his complaints to President Gaviria, who dismissed them as harmless. Accounts of Escobar's continued criminal activities while in prison began to surface in the media,[306] Although there were unconfirmed rumors that Escobar still maintained control over the Medellín Cartel, Henry Pérez, leader of the paramilitaries of Magdalena Medio, was killed in the middle of religious celebrations in Puerto Boyacá. Pérez, who had long been an ally of Escobar and one of those who attempted to kill Galán in 1989, entered into conflict with Escobar, who ordered his assassination, although Escobar would deny any accusation.[307][308][309][310][311][excessive citations]

Escobar increased the amount of money he demanded from his partners, which gradually began to bother them. On July 4, 1991, 'Tyson' and 'Titi' accidentally find a stash belonging to Gerardo Moncada with 23 million dollars. They both report their discovery to 'Chopo' and he reports it to Escobar. 'Titi' along with 'Chopo' steal the money and take it to La Catedral. Escobar meets Moncada and Galeano believing that they are hiding drug money from him. After a slight argument, both men offer Escobar a good part of the money found. 'Chopo' goads Escobar that both men may have more money hidden, which Moncada and Galeano flatly deny. Escobar believes 'Chopo' more and orders him and 'Popeye' to kill, dismember and incinerate them.[312][313][314][315] Escobar had also invited the Castaño brothers to appear at 'La Catedral', but they did not attend.[316] Escobar had also summoned the Castaño brothers to appear at 'La Catedral', but they did not show up due to an apparent landslide on the road. 'Chopo' left La Catedral in Federico Galeano's car, but when Don Berna, Galeano's head of security, accompanied by Rafael Galeano, demanded to see Federico, a shootout broke out in which Galeano ended up wounded in the arm, but Don Berna and Galeano managed to escape and the Castaño brothers met up. Seeing the reaches to which Escobar had reached, they decided to join forces to create the vigilante group Los Pepes (Persecuted by Pablo Escobar).[317][318][319][320][321][excessive citations]

While the rest of the relatives of Moncada and Galeano were murdered in Medellín and its surrounding towns, Mireya Galeano joined the Pepes, and was helped by Rodolfo Ospina Baraya 'Chapulín', secret associate of the Medellín Cartel and grandson of the former president Mariano Ospina Pérez, sends a video to the Prosecutor General's Office giving statements about what happened in La Catedral.[322][323][324] Furious, general prosecutor Gustavo De Greiff showed the evidence to Gaviria, who, outraged, called a Security Council attended by the ministers of defense and justice, and the commanders of the army and the police, Fernando Britto, head of DAS, Arrieta and Fabio Villegas, secretary general of the presidency; which prompted the government to attempt to move him to a more conventional jail on 22 July 1992. During 21 July, 1991, it was decided that the army would take over the prison in order to take Escobar and his men prisoner and transfer them to a military garrison. It was also decided that those in charge of this task would be Colonel Hernando Navas Rubio, national director of prisons, and Eduardo Mendoza, vice-minister of justice. Both went in the same car to El Dorado airport in Bogotá, unaware of their functions. Upon arriving at the José María Cordova airport in Rionegro, they were informed by Brigadier General Gustavo Pardo Ariza.[325][326][327]

Navas, along with the army, would begin the militarization of the prison and coordinate the transfer of Escobar and his men, while Mendoza, as vice-minister, would represent the government in the operation. However, the operation failed; most of the soldiers were resting because they had marched on July 20th to commemorate Independence Day; several trucks with not many soldiers were going directly to the mountain where La Catedral was located, something that Escobar noticed through the peasants in the area on his payroll; in addition to the chain of errors committed that same night. With the permission of Pardo Ariza, Navas and Mendoza arrived at La Catedral. Navas entered disobeying the direct orders of the presidency and informed Escobar of the government's decision to militarize the prison and transfer it to a military base. Escobar demanded that a government representative attend, making Mendoza enter as well. Feeling betrayed by the government for not fulfilling what was agreed in surrender, Escobar called the Nariño Palace. Mendoza spoke first and Escobar, when he came to the phone, asked to speak to the president or, failing that, to the minister of justice, but both refused. Escobar took both officials hostage and made a second call to the Presidential Palace; but the secretary general Fabio Villegas Restrepo answered, announcing to Navas and Mendoza that they were dismissed.[328][329][330][331][332][333][excessive citations] Escobar's influence allowed him to discover the plan in advance and make a successful escape; mistakenly thinking that he would be extradited or killed, Escobar and his men flee from La Catedral; they kick a wall made of plaster instead of concrete, and take advantage of the darkness and fog in the area and the blackout of the 'Gaviria Hour', spending the remainder of his life evading the police.[334][285][335][336]In the early hours of July 22, the missing soldiers arrive and invade La Catedral, rescuing Navas and Mendoza and capturing a few of Escobar's hitmen. It is also discovered that the soldiers guarding the prison outside had been bribed by Escobar.[337][338][339][340][341][342][343][excessive citations]

Escape and final stage

Escobar's escape represented the biggest mockery of the Gaviria government in the eyes of the public, and Colombian justice would end up being discredited internationally.[344] The government reactivated the Elite Group, renaming it the Search Bloc, a body made up of the National Police and the National Army with the collaboration of the DEA to hunt down the fugitives and dismantle their criminal empire once and for all. The leaders of the Cali Cartel were responsible for unleashing the war again, by activating a car bomb in Medellín that they attributed to their enemies from Antioquia, at the same time that they decided to finance Los Pepes.[345][346][347]

While Escobar ordered the murder of police officers, new terrorist attacks with car bombs and some selective assassinations, the Search Bloc was only able to carry out raids and the shooting down of 'Tyson' on October 28, 1992, corrupt police elements allied with Los Pepes in order to finish off Escobar and his thugs, specially Police Colonel Danilo González.[348] Following a chess-like tactic; In order to take pieces from the opponent, both the Pepes and the Search Bloc were dealing blows to Escobar's hitman structure.[349][350] Although the Colombian government offered a reward of one billion Colombian pesos for the capture of Escobar, the US offered two million dollars. Escobar and his men did not sit still and continued their crime spree. Escobar's hitmen murdered the faceless public order judge Myriam Rocío Vélez;[351][352][353] the captain of the judicial police Fernando Posada Hoyos, one of the staunchest enemies of the Medellín Cartel;[354][355] and they kidnapped and murdered Lizandro Ospina Baraya, brother of 'Chapulín' and also grandson of former president Ospina Pérez in retaliation for testifying against Escobar in court for the murder of Galán.[356][357] The car bombs continued in the streets of several Colombian cities.[358] By March 29, 1993, most of Escobar's hitmen had been arrested or killed. The final surrender of 'Popeye', 'El Mugre' and 'El Osito', Escobar's older brother, stands out on October 28, 1992. That surrender had been one of Escobar's gestures trying to negotiate another surrender, which was ignored by the government demanding an unconditional surrender.[359][360][361][362]

For their part, Los Pepes dedicated themselves to killing Escobar's front men, accountants, lawyers and family members, as well as destroying their properties and undermining their finances.[363][364][365][98][366][367][368][369] Although Escobar also responded in kind and publicly revealed their names, this did not prevent both Los Pepes and the Search Bloc from maintaining a superior advantage over Escobar, whose last car bomb attack under their orders was in the Centro 93 Mall in northern Bogotá, on April 15, 1993, ironically, the day on which the deadline imposed by the government on Escobar for his unconditional surrender expired, which was not an option for Escobar while he and/or his family were in danger of dying at the hands of Los Pepes.[370][371][372][373]

On April 17, 1993, Guido Parra Montoya, Escobar's lawyer, and his son Guido Andrés Parra were kidnapped and murdered by the Pepes, and their corpses were abandoned in an unpopulated area of Envigado.[374][375][376][377]

Death

That they will never catch me in the great fucking life, and that from the jungle I will order them all to be killed and in the long run the ones who will lose will be them.

— Audio intercepted of Escobar speaking in a threatening tone.[378]

Although he managed to evade the Search Bloc for another 6 months, by October 1992, Escobar had lost all of his power; his last chief of bodyguards, 'El Angelito', was killed by the police on October 6 along with his brother, Álvaro Puerta.[379] Escobar tried on several occasions to negotiate his surrender in exchange for safeguarding his family, but his proposal found no support in the government. His mother was the victim of several unsuccessful assassination attempts by the Pepes,[380] and his brother Roberto, despite being in prison, was the victim of a letter bomb sent by the Pepes that left him blind in one eye.[381][382]

Escobar faced threats from the Colombian police, the U.S. government and his rivals Pepes, and the Cali Cartel. By this reason Escobar attempted to get his family (his wife Victoria Henao and his children Juan Pablo along with his girlfriend Doria Andrea Ochoa, and his youngest daughter Manuela)[383] out of the country; twice to the United States without any success, and finally to Europe with a stopover in Germany, but the German authorities were warned by both the Colombian police and the DEA (with two agents on board the plane), and they were all immediately deported to Colombia.[384][385][386][387] Upon arrival at El Dorado airport, the Escobar Henao family was taken into the custody of the Colombian authorities and confined to an apartment in the Hotel Tequendama Residences in the International Center of Bogotá, under strict police surveillance.[388][389][390]

Knowing that the Tequendama Residences belonged to the Retirement Fund of the Military Forces, Escobar knew that the phones were tapped. The government took advantage of Escobar's constant concern for his family, which they used as bait to locate him with French and British technology that they had acquired with the help of the DEA; which not only identified the calls but also triangulated his location.[391] Escobar also knew that he could not spend more than two minutes making a call. When calling Residencias Tequendama he used to fake his voice, pretending to be a reporter, in order to be able to speak to his family.[392][393] With no men or money, Escobar, who was already suffering from gastritis, tried to create a guerrilla movement called 'Antioquia Independiente', but instead preferred to make approaches to the FARC to become an accountant for the money from extortion and kidnappings, and for the drug trafficking business in which they had begun to venture a few years earlier. None of these initiatives came to fruition.[394][395]

On December 1, 1993, Escobar celebrated his last birthday accompanied by his cousin Luzmila Gaviria,[396][397] his mother and Álvaro de Jesús Agudelo 'Limón', the latter being his last bodyguard but who had previously been his brother Roberto's driver.[396][398][399] The next day, on 2 December 1993, desperate, Escobar called his family again. Although in the previous days Escobar had been moving in a taxi accompanied by 'Limón' to avoid being located and calling for less than 2 minutes, Escobar remained inside the house, but that day he managed to avoid being located by speaking for less than two minutes. Following the same routine, Escobar continued calling pretending to be a journalist, but the second call went over two minutes, so he was immediately located. Escobar was found in a house in Los Olivos neighbourhood, a middle-class residential area of Medellín close to Atanasio Girardot Sports Complex by Colombian special forces, using technology provided by the United States, which allowed them to trace Escobar's location after he made a long call to his family. Police tried to arrest Escobar but the situation quickly escalated to an exchange of gunfire. Escobar was shot and killed while trying to escape from the roof, along with 'Limón', who was also shot. He was hit by bullets in the torso and feet, and a bullet, which struck him in the head, killing him. This sparked debate about whether he killed himself or whether he was shot and killed.[46][400][401][402][403][404][excessive citations]

There are several hypotheses about his death:

- Escobar committed suicide by shooting himself below the right ear.[405] This version coincides with the motto of Los Extraditables: "We prefer a grave in Colombia than a prison in the United States" and is the version defended by his family.[406][407][408][409][410][411][412][413][414][excessive citations]

- A sniper from the group Los Pepes shot him.[415]

- A DIJIN officer who was part of the Search Block shot him.[415]

- A Delta Force (DF) sniper shot him.[416]

- The coup de grace was fired by Colonel Hugo Heliodoro Aguilar, who led the assault group that arrived at the house.[417][418][419][420]

- He was shot by Carlos Castaño Gil, the top leader of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), according to a confession by a paramilitary named José Antonio Hernández, known by the alias John.[421][422]

- He was shot dead by a squad of the Search Bloc, which is the official version of events.[423]

Aftermath of his death

Soon after Escobar's death and the subsequent fragmentation of the Medellín Cartel, the cocaine market became dominated by the rival Cali Cartel until the mid-1990s when its leaders were either killed or captured by the Colombian government. The Robin Hood image that Escobar had cultivated maintained a lasting influence in Medellín. Many there, especially many of the city's poor whom Escobar had aided while he was alive, mourned his death, and over 25,000 people attended his funeral. Some of them consider him a saint and pray to him for receiving divine help. Escobar was buried at the Monte Sacro Cemetery.[424]

Virginia Vallejo's testimony

On 4 July 2006, Virginia Vallejo, a television anchorwoman romantically involved with Escobar from 1983 to 1987, offered Attorney General Mario Iguarán her testimony in the trial against former Senator Alberto Santofimio, who was accused of conspiracy in the 1989 assassination of presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán. Iguarán acknowledged that, although Vallejo had contacted his office on 4 July, the judge had decided to close the trial on 9 July, several weeks before the prospective closing date. The action was seen as too late.[425][426]

On 18 July 2006, Vallejo was taken to the United States on a special flight of the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) for "safety and security reasons" due to her cooperation in high-profile criminal cases.[427][428] On 24 July, a video in which Vallejo had accused Santofimio of instigating Escobar to eliminate presidential candidate Galán was aired by RCN Television of Colombia. The video was seen by 14 million people, and was instrumental for the reopened case of Galán's assassination. On 31 August 2011 Santofimio was sentenced to 24 years in prison for his role in the crime.[429][430]

Role in the Palace of Justice siege

Among Escobar's biographers, only Vallejo has given a detailed explanation of his role in the 1985 Palace of Justice siege. She stated that Escobar had financed the operation, which was committed by M-19; she blamed the army for the killings of more than 100 people, including 11 Supreme Court magistrates, M-19 members, and employees of the cafeteria. Her statements prompted the reopening of the case in 2008; Vallejo was asked to testify, and many of the events she had described in her book and testimonial were confirmed by Colombia's Commission of Truth.[431][432] These events led to further investigation into the siege that resulted with the conviction of a high-ranking former colonel and a former general, later sentenced to 30 and 35 years in prison, respectively, for the forced disappearance of the detained after the siege.[433][434] Vallejo would subsequently testify in Galán's assassination.[435] In her book, Amando a Pablo, odiando a Escobar (Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar), she had accused several politicians, including Colombian presidents Alfonso López Michelsen, Ernesto Samper, and Álvaro Uribe of having links to drug cartels.[436]

The surviving members of the extinct guerrilla group have reiterated their statements that Escobar never financed the assault taking into account the war they waged with his former armed wing MAS, and that the assault only had political purposes in the midst of his 'Campaign for Colombia'.[437] The existence of original and copied files on the crimes of the Medellin Cartel in the Foreign Ministry, US and Colombian courts, and in the American embassy in Bogota refutes any theory of Escobar's involvement.[107][438]

Relatives

Escobar's widow (María Henao, now María Isabel Santos Caballero), son (Juan Pablo, now Sebastián Marroquín Santos) and daughter (Manuela) fled Colombia in 1995 after failing to find a country that would grant them asylum.[439] Despite Escobar's numerous and continual infidelities, Maria remained supportive of her husband. Members of the Cali Cartel even replayed their recordings of her conversations with Pablo for their wives to demonstrate how a woman should behave.[440] This attitude proved to be the reason the cartel did not kill her and her children after Pablo's death, although the group demanded and received millions of dollars in reparations for Escobar's war against them. Henao even successfully negotiated for her son's life by personally guaranteeing he would not seek revenge against the cartel or participate in the drug trade.[441]