Manaw Gododdin

Manaw Gododdin was the narrow coastal region on the south side of the Firth of Forth, part of the Brythonic-speaking Kingdom of Gododdin in the post-Roman Era. It is notable as the homeland of Cunedda prior to his conquest of North Wales, and as the homeland of the heroic warriors in the literary epic Y Gododdin. Pressed by the Picts expanding southward and the Northumbrians expanding northward, it was permanently destroyed in the 7th century and its territory absorbed into the then-ascendant Kingdom of Northumbria.

The lands both south and north of the Firth of Forth were known as 'Manaw', but from the post-Roman Era forward, only the southern side is referred to as Manaw Gododdin, the Manaw associated with the people of Gododdin. Manaw Gododdin was adjacent to – and possibly included in – Eidyn, the region surrounding modern Edinburgh.[1]

Though Manaw Gododdin was located within the territory of modern Scotland, as a part of Yr Hen Ogledd (English: The Old North), it is also an intrinsic part of Welsh history, as both the Welsh and the Men of the North (Welsh: Gwŷr y Gogledd) were self-perceived as a single people, collectively referred to as Cymry.[2] The arrival in Wales of Cunedda of Manaw Gododdin in c. 450 is traditionally considered to be the beginning of the history of modern Wales.

The name appears in literature as both Manaw Gododdin and Manau Gododdin. The modern Welsh form is spelled with a 'w'.

Sources of information

[edit]Background: confusion with the Isle of Man

The Isle of Man is known in Welsh as Ynys Manaw, and this has introduced ambiguity in literary and historical references where Manaw (or Manau) was used without further elaboration, as to whether the reference was to Manaw Gododdin or to the Isle of Man.

A similar problem exists in Irish, where both the northern Pictish Manaw and the southern Manaw Gododdin are referred to as Manann (or Manonn). Certain forms of the Irish name for the Isle of Man produce the genitive name Manann (or Manonn). Either place can be inferred if the context is uncertain.

Historia Brittonum

In the Historia Brittonum, Nennius says that "the great king Mailcun reigned among the Britons, i.e., in Gwynedd". He adds that Maelgwn's ancestor Cunedda arrived in Gwynedd 146 years before Maelgwn's reign, coming from Manaw Gododdin, and expelled the Scots (i.e. the Gaels) with great slaughter.[3][4]

In the chapters of the Historia Brittonum discussing the circumstances leading up to the death of Penda of Mercia in 655, Oswiu of Northumbria is besieged at "Iudeu" by Penda and his allies and offers up the wealth (i.e. the royal dignities) of that place, which had been recently captured by the Northumbrians (the "Restoration of Iudeu", so-called), as well as that which he held "as far as Manaw".[5][6] In Latin the phrase is usque in manau pendae. The recensions are not all consistent on this point. There is also esque in manu pendae[7] and esque in manum pendae,[8] which if reliable, would allow for a different interpretation, as manus (4th declension) is Latin for hand (as in into the hand [of Penda]).

Welsh genealogies

The royal genealogies provide no information per se about Manaw Gododdin. However, as it was the homeland of Cunedda and he was the progenitor of many Welsh royal lines, he is prominent in the Harleian genealogies.[9] Some of these genealogies reappear in Jesus College MS. 20,[10] though it focuses mainly on the ancient royalty of South Wales. All of Cunedda's descendants claim a heritage from Manaw Gododdin.

Annals of Ulster

According to the Annals of Ulster, Áedán mac Gabráin, king of Dál Riata, was victor in a "bellum Manonn" (English: Battle or War at Manonn) in 582 (his opponent is not given).[11]

There is some scholarly disagreement as to the place meant, whether Manaw Gododdin or the Isle of Man. Both are plausible and have some supporting evidence, but lacking hard information, the issue probably will not be settled definitively. Both those favouring the Isle and those favouring Manaw Gododdin say so and include a footnote to the effect that the balance seems to be on one side or the other, with accompanying arguments.[12][13]

Annals of Ulster, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The Annals of Ulster say that in 711, the Northumbrians defeated the Picts at the campus Manann, the field of Manaw. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives the year as 710, saying that "Beorhtfrith the ealdorman fought against the Picts between Haefe and Caere".[14]

This is assumed to be between the Rivers Avon (Haefe) and Carron (Caere). William Forbes Skene first argues for it in The Four Ancient Books of Wales (1868), noting that the Avon rises in the place still known as Slamannan Moor (i.e. Sliabhmannan, the Moor of Manann).[15] He repeats the conjecture in his Celtic Scotland (1886),[16] and later historians have accepted his suggestion, citing him as the source.[17][18][19]

Name survivals

[edit]

The Gaelic form of the name is Manann. Like Manaw, its etymology is uncertain, with neither form necessarily owing a heritage to the other. In the Early Middle Ages, Brythonic was replaced by Gaelic in the region of Manaw. It was common to retain original place-names, but to alter the pronunciation to be in accord with the language that was then current.

Manaw Gododdin

South of the Firth of Forth and River Forth the name survives in the name of Slamannan Moor and the village of Slamannan, in Falkirk.[17] This is derived from Sliabh Manann, 'Mount Manann'.[21] It also appears in the name of Dalmeny, some 5 miles northwest of Edinburgh. It was formerly known as Dumanyn, assumed to be derived from Dun Manann.[21]

Pictish Manaw

North of the Forth it survives in the name of the burgh of Clackmannan and the eponymous county of Clackmannanshire.[17] This is derived from Clach Manann, the 'stone of Manann',[21] referring to a monument stone located there.

Treatment by historians

[edit]With little known about Manaw Gododdin, there is little that can be said of it with any authority. Aside from parenthetical references to it as Cunedda's homeland, discussion is scant. William Forbes Skene (The Four Ancient Books of Wales, 1868) has a chapter on "Manau Gododdin and the Picts",[22] and later historians either repeat him or cite him, but do not add more. Kenneth Jackson (The Gododdin, 1969) provides the same information as Skene, enhanced by his notice and commentary on some of the speculations and conjectures made by historians in the century since Skene published his work. He adds that the early Irish form of the name Gododdin is Fortudán.[23]

John Koch (Celtic Culture, 2005) incorporates some of Skene's material on Manaw (and credits Skene for it), including an independent view of the historical record (reaching the same general conclusions as Skene), but also asserting conjectures as though they were facts (e.g., asserting that the "Iudeu" mentioned in the Historia Brittonum was at Stirling).[24]

John Rhys (Celtic Britain, 1904) both repeats and cites Skene, but adds nothing new.[25] John Edward Lloyd (History of Wales, 1911) makes only a few comments about Manaw in passing,[26] and John Davies (History of Wales, 1990) omits even that.[27] Christopher Snyder (An Age of Tyrants, 1998) mentions Manaw twice in passing, saying nothing about it there or in his references to the literary Y Gododdin.[28] D. P. Kirby (The Earliest English Kings, 1991) mentions Manaw several times, but only in passing and with no information about it.[29] Alistair Moffat (Before Scotland, 2005) makes several passing references to Manaw Gododdin and Gododdin.[30]

In general, there is as much information about Manaw to be found in literary discussions as in historical ones and often more, though it is not more than Skene provided. For example, John Morris-Jones, in his comprehensive discussion of works attributed to Taliesin (Y Cymmrodor XXVIII, 1918), repeats and cites the information provided by Skene that is typically omitted in historical works.[31]

Regional history

[edit]

The earliest reliable information on the region of the Firth of Forth during the time when Manaw Gododdin existed is from the archaeology of Roman Britain. The homeland of the Votadini, like those of the Damnonii and Novantae, was not planted with forts, suggesting (but not confirming) that the peoples of these regions had reached an amicable understanding with the Romans (such as an unequal alliance), and consequently these tribes or kingdoms continued to exist throughout the Roman Era. There is no indication that the Romans ever waged war against any of these peoples.

However, the Romans were frequently at war with the more northerly peoples now known as Picts, and their military lines of communication (i.e. their roads) were well-fortified. This includes the road through Manaw Gododdin, the northern end of Dere Street.

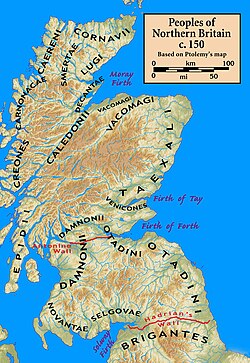

The earliest reliable historical reference to the peoples of Northern Britain is from the Geography of Ptolemy in c. AD 150. He says that this was the territory of the Otadini (i.e. the Votadini),[32] a people later known as the Kingdom of Gododdin (i.e. the Kingdom of the Votadini). Their lands were along the coast of south-eastern Scotland and north-eastern England, and included the lands along the Firth of Forth, both north and south of it.

Ptolemy says that in 150 both the Damnonii and the Otadini possessed the land north of the Firth of Forth and south of the Firth of Tay. The Picts were constantly pressing southward, and by the early 3rd century the Roman Emperor Severus ineffectively campaigned against them. Known then as the Maeatae, the local Picts would ultimately push south to the Firth of Forth and beyond, and by the 7th century the Votadini were being squeezed between them and the Anglian Bernicians, who were expanding northward.

Neither Gododdin nor Manaw Gododdin could have existed as a kingdom beyond the 7th century. The Kingdom of Northumbria was ascendant, and it would conquer all of Scotland south of the Firths of Clyde and Forth. The definitive years were the middle of the 7th century, when Penda of Mercia led an alliance of Mercians, Cymry (both from the north and from Gwynedd), East Anglians, and Deirans against Bernicia. Penda was defeated and killed at the Battle of Winwaed in 655, ending the alliance and cementing Bernician control over all of Britain between the English Midlands and the Scottish firths. Bernicia was again united with Deira to form Northumbria as the premier military power of the era. Alt Clut soon re-established its independence, but all other Brythonic kingdoms north of the Solway and Tyne were gone.

Citations

[edit]- ^ Bromwich 2006:113–114

- ^ Lloyd 1911:191–192, History of Wales Vol I., Note to Chapter VI, the Name "Cymry"

- ^ Giles 1841:34, The Works of Nennius (English translation)

- ^ Giles 1847:341, Historia Britonnum (in Latin)

- ^ Skene 1886:254–255, Celtic Scotland, The Four Kingdoms.

- ^ Anderson 1908:24, Scottish Annals from English Chroniclers

- ^ Stevenson 1838:54, Nennii Historia Britonum, Ch. 65.

- ^ Giles 1847:342, Historia Brittonum

- ^ Phillimore 1888:141–183, The Annales Cambriae and Old Welsh Genealogies, from Harleian MS. 3859

- ^ Phillimore 1887:83–92, Pedigrees from Jesus College MS. 20

- ^ Reeves 1857:371, Ulster Chronicle, 582: "Bellum Manonn, in quo victor erat Aedan mac Gabhrain."

- ^ Miller, Molly (1980), "Hiberni Reversuri" (PDF), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, (1978 – 1980), vol. 110, Society of Antiquaries of Scotland (published 2002), pp. 305–327, ISSN 0081-1564, for example, favouring the Isle on p. 320 with footnote 65 giving reasons.

- ^ Reeves 1857:371, Ulster Chronicle, for example, favouring Manaw Gododdin, with footnote 4 giving reasons.

- ^ Reeves 1857:380, Annals of Ulster, 711: "Strages Pictorum in Campo Manonn apud Saxones, ubi Finnguine filius Deileroith immatura morte jacuit.".

- ^ Skene 1868a:91, The Four Ancient Books of Wales Vol. I, Manau Gododin and the Picts.

- ^ Skene 1886:270, Celtic Scotland, The Four Kingdoms.

- ^ a b c Rhys 1904:155, Celtic Britain, The Picts and the Scots.

- ^ Anderson 1908:50, Scottish Annals From English Chroniclers

- ^ Kirby, D. P. (1990), "The northern Anglian hegemony", The Earliest English Kings (Second ed.), London: Routledge (published 2000), pp. 85–86, ISBN 0-415-24211-8

- ^ Forsyth, Valerie (7 March 2018). "A Walk in the Past: History of the Mannan Stone". Alloa Advertiser. Retrieved 4 April 2018.

- ^ a b c Rhys 1901:550, Celtic Folklore Vol. II, Place-Name Stories.

- ^ Skene 1868a:77–96, Celtic Scotland, Manau Gododdin and the Picts

- ^ Jackson 1969:69–74, The Gododdin, Appendix 1: Gododdin and Manaw Gododdin.

- ^ Koch 2005, Celtic Culture

- ^ Rhys 1904:77–96, Celtic Britain

- ^ Lloyd 1911:116, 117, 118, 184, 323, 324, A History of Wales Vol. I

- ^ Davies 1990, A History of Wales

- ^ Snyder 1998:172, 195, 106, 175, 248, 254, 299, 341, 343, An Age of Tyrants

- ^ Kirby 1991:69, 86, 90, 100, 147, The Earliest English Kings

- ^ Moffat 2005, Before Scotland

- ^ Morris-Jones 1918, Taliesin

- ^ Ptolemy 150, Geographia 2.2, Albion Island of Britannia.

References

[edit]- Anderson, Alan Orr (1908), Scottish Annals From English Chroniclers A.D. 500 to 1286, London: David Nutt

- Bromwich, Rachel (2006), Trioedd Ynys Prydein: The Triads of the Island of Britain, University Of Wales Press, ISBN 0-7083-1386-8

- Davies, John (1990), A History of Wales (First ed.), London: Penguin Group (published 1993), ISBN 0-7139-9098-8

- Giles, John Allen, ed. (1841), The Works of Gildas and Nennius, London: James Bohn — English translation

- Giles, John Allen, ed. (1847), History of the Ancient Britons, vol. II (Second ed.), Oxford: W. Baxter (published 1854) — in Latin

- Jackson, Kenneth Hurlstone (1969), The Gododdin, Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, ISBN 0-85224-353-7

- Kirby, D. P. (1991), The Earliest English Kings, London: Routledge (published 1992), ISBN 0-415-09086-5

- Koch, John T., ed. (2005), Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia, ABL-CLIO (published 2006), ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0

- Lloyd, John Edward (1911), A History of Wales from the Earliest Times to the Edwardian Conquest, vol. I (Second ed.), London: Longmans, Green, and Co. (published 1912)

- Moffat, Alistair (2005), Before Scotland: The Story of Scotland Before History, New York: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 978-0-500-28795-8

- Morris-Jones, John (1918), "Taliesin", in Evans, E. Vincent (ed.), Y Cymmrodor, vol. XXVIII, London: Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion

- Phillimore, Egerton, ed. (1887), "Pedigrees from Jesus College MS. 20", Y Cymmrodor, vol. VIII, Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, pp. 83–92

- Phillimore, Egerton (1888), "The Annales Cambriae and Old Welsh Genealogies, from Harleian MS. 3859", in Phillimore, Egerton (ed.), Y Cymmrodor, vol. IX, Honourable Society of Cymmrodorion, pp. 141–183

- Ptolemy (150), Thayer, Bill (ed.), Geographia, Book 2, Chapter 2: Albion island of Britannia, LacusCurtius website at the University of Chicago (published 2008), retrieved 26 April 2008

- Reeves, William (1857), The Life of St. Columba Written by Adamnan, to which are added Copious Notes and Dissertations, Dublin: Irish Archaeological and Celtic Society

- Rhys, John (1901), Celtic Folklore: Welsh and Manx, vol. II, Oxford: Oxford University

- Rhys, John (1904), Celtic Britain (3rd ed.), London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge

- Skene, William Forbes (1868a), The Four Ancient Books of Wales, vol. I, Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas (published 1868)

- Skene, William Forbes (1868b), The Four Ancient Books of Wales, vol. II, Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas (published 1868)

- Skene, William Forbes (1886), Celtic Scotland: A History of Ancient Alban (History and Ethnology), vol. I (2nd ed.), Edinburgh: David Douglas, ISBN 9780836949766

- Stevenson, Joseph (1838), Nennii Historia Britonum, London: Literary Society

- Snyder, Christopher A. (1998), An Age of Tyrants: Britain and the Britons A.D. 400–600, University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, ISBN 0-271-01780-5