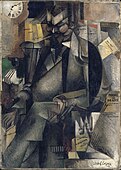

Man with a Pipe

| Man with a Pipe (Portrait of an American Smoking) | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Jean Metzinger |

| Year | 1911-12 |

| Type | Black & white reproduction |

| Medium | Oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 92.7 cm × 65.4 cm (36.5 in × 25.75 in) |

| Location | The painting (shown here in black and white half-tone) has been missing from Lawrence University, Appleton, Wisconsin, since 1998, having disappeared while in transit on loan.[1] |

Man with a Pipe, also referred to as Portrait of an American Smoker, Portrait of an American Smoking, American Smoking and American Man, is a painting by the French Cubist artist Jean Metzinger. The work was reproduced on the cover of catalogue of the Exhibition of Cubist and Futurist Pictures, Boggs & Buhl Department Store, Pittsburgh, forming part of a show in 1913 that traveled to several U.S. cities: Milwaukee, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, New York, and Philadelphia.

In 1914 a catalogue was printed for the occasion of the Milwaukee leg of the show, 16 April to 12 May, titled Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture in "The Modern Spirit", hosted by the Milwaukee Art Society. Artists represented included Lucile Swan, Amadeo de Souza Cardoso, Manierre Dawson, Marcel Duchamp, Jacques Villon, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger, Gustave Miklos, Francis Picabia, and Henry Fitch Taylor. Metzinger's painting titled Portrait of "American Smoking" figured as No. 101 of the catalogue.[2] And much as the outcry that resulted from the Cubists works at the Armory Show in New York, Chicago and Boston, this traveling exhibition created an uproar in other major U.S. cities. Though he did not exhibit with his Cubist colleagues at the Armory Show in 1913, Metzinger, with this painting and others, contributed in 1913 to the integration of modern art into the United States.

Man With a Pipe was gifted to the Wriston Art Center Galleries, Lawrence University, by Howard Green.[3][4] In 1956 American Man was requested for touring by the American Federation of Arts via the State Department. The work was sent to Sweden and subsequently shown throughout western Europe. It was returned to the college in September 1957.[5] The painting, shown here in a black and white half-tone photographic reproduction, has been missing since 1998, having disappeared in transit while on loan, between 27 July and 2 August.[1][6]

Description

[edit]Man with a Pipe is an oil painting on canvas with dimensions 93.7 × 65.4 cm (36.5 by 25.75 inches), signed JMetzinger lower right. The work represents a man sitting at a table upon which is placed a mug of beer. The man, an American according to the title of the work, has his arms crossed and has a pipe in his mouth. He wears a jacket and tie. To the right is a vase with a painting of a sail boat in front of a setting sun above. To the sitters left can be seen half of a portrait in a round frame.[7][8] While the Man with a Pipe is treated in an extreme form of Cubism, the two works hanging on the wall behind the sitter are not Cubist at all, albeit, they are stylized. One represents a boat with a setting or rising sun, the other, a portrait placed in a semi-circle, almost an echo of the Man with a Pipe.

Rather than simultaneously superimposing successive images to depict motion, Metzinger represents the subject at rest from multiple angles. The dynamic role is played by the artist rather than the subject. By moving around the subject the artist captures several important features at once; such as the profile and frontal view. And because motion involves time, several intervals or moments are captured simultaneously (a process coined by Metzinger called simultaneity or multiplicity). Moods and expressions within each facet may be different, reflecting change over time. The result, according to Metzinger is a more complete representation of the subject matter (a 'total image') than would otherwise have resulted from one image taken at one instant. Each facet reveals something new and different about the subject. Sutured together, these facets would form a more complete image than an otherwise static representation seen from one point of view; what Metzinger called a "total image".[8][9]

In addition to the inequality of parts being granted as a prime condition of Metzinger Cubism, there are two methods of regarding the division of the canvas. Both methods, according to Metzinger and Gleizes (1912)[10] are based on the relationship between color and form:

According to the first, all the parts are connected by a rhythmic convention which is determined by one of them. This—its position on the canvas matters little—gives the painting a centre from which the gradations of colour proceed, or towards which they tend, according as the maximum or minimum of intensity resides there.

According to the second method, in order that the spectator, himself free to establish unity, may apprehend all the elements in the order assigned to them by creative intuition, the properties of each portion must be left independent, and the plastic continuum must be broken into a thousand surprises of light and shade. [...]

Every inflection of form is accompanied by a modification of colour, and every modification of colour gives birth to a form. (Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Du "Cubisme", 1912)[10]

Background

[edit]The success of the 1913 Armory Show in New York can be seen by the influence of modern art on fashion design, home decoration and advertising that appeared during and after the exhibition. Store windows began displaying gowns styled after Cubist paintings. Women painted their faces and wore brightly colored wigs. Fashion design became a way of integrating modern art into daily life. Walt Kuhn, a painter and an organizer of the Armory Show welcomed the union between art and popular culture.[11] The Armory Show according to Kuhn benefited everyone:

The late President Coolidge once said, "America's business is business." Therein lies the answer. We naive artists, we wanted to see what was going on in the world of art, we wanted to open up the mind of the public to the need of art. Did we do it? We did more than that. The Armory Show affected the entire culture of America. Business caught on immediately, even if the artists did not at once do so. The outer appearance of industry absorbed the lesson like a sponge. Drabness, awkwardness began to disappear from American life, and color and grace stepped in. Industry certainly took notice. The decorative elements of Matisse and the Cubists were immediately taken on as models for the creation of a brighter, more lively America. (Walt Kuhn)[11][12]

Department stores became hosts to modern art, holding the first exhibitions of Cubist paintings after the Armory Show, becoming perhaps the first corporate sponsors of an exhibition. After the Armory Show closed in Boston (April 1913), the American department store Gimbel Brothers (Gimbels) began organizing a Cubist exhibition that would travel to five different cities, Milwaukee, Cleveland, Pittsburgh, New York, and Philadelphia, over the course of one year.[11] The Milwaukee exhibition of Cubist works—including paintings by Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Fernand Léger and Jacques Villon—opened 11 May and lasted approximately six weeks, until late June 1913.[13] Gimbels sponsored the show in Milwaukee, New York, and Philadelphia. In Cleveland, William Taylor Son & Co. continued the exhibition, inviting customers to view "original Cubist paintings by masters of the style" (Aaron Sheon, 93).[11] Boggs and Buhl's hosted the show in Pittsburgh, enticing customers with a painting by Metzinger, Portrait of an American Smoker on the cover of its catalogue, and a balladry by Arthur Burgoyne published in the Pittsburgh Chronicle Telegraph:

Aesthetical highbrows these days are aflame.

With zeal for the Cubist or Futurist game.

The painters began it. Van Gogh and Matisse

And some others intent on disturbing the peace

Of the art-loving public came right to the fore

With such puzzles in color as caused an uproar.

But they rightfully banked on the constant demand

For things that the populace can't understand

And they found that all classes, both highbrows and rubes,

Would fall for their curious futurist cubes.

—Arthur Burgoyne, 1913[11]

Burgoyne's poem indicates his recognition of Cubism's appeal as an anti-bourgeois art form, essential to creating a market for the new art.[11]

Just as the Cubists at the Armory show in New York, Chicago and Boston, this traveling exhibition created an uproar in other major U.S. cities. Neither the public nor the critics minced their words. Metzinger's American Smoker was singled out in an article published in The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, titled New Cubist Pictures, Latest From Paris Fail to Satisfy Art Enthusiasts in Cleveland, O.:

Cubists' paintings, imported direct from Paris, now are being shown in the store in Cleveland, Ohio, says the Cleveland Plain Dealer, but the hundreds of art enthusiasts who are thronging to the place have difficulty in understanding the pictures, owing to the meagerness of details in the catalogue. For instance: Exhibit F shows an "American Smoker," by Jean Metzinger. Who is the American? Where is the rest of his face? Was it carved off in a duel at one of the foreign universities or did he dislike it and have it remodeled? Such are some of the questions being asked by those most interested—and the catalogue merely says "American Smoking."[14]

Of Albert Gleizes's monumental Femmes cousant (Women Sewing), Kröller-Müller Museum,[15] the anonymous author of the article writes:

Then there is Exhibit H—"Harmony of Colors," which the catalogue describes as follows: "Subject three women sewing beside the road; to the right a large tree; in the background a landscape is seen through the arch of the viaduct." Where are the women? Only one mouth is visible. Where are the others? Have they combined their identities and do they use only one mouth between them? Such are the questions but there are no answers.[14]

That Gimbels and other department stores exhibited Cubist works to attract customers exemplifies the extent to which the exhibition of French Paintings and Sculpture in Gallery 1 of the Armory Show (dubbed the "chamber of horrors") attracted the attention of those outside the art world. Corporate sponsorship of modern art continued after the initial 1913 department store shows, with Wanamaker's, Macy's and Lord and Taylor's participating in exhibiting modern art during the 1920s.[11]

"Now that the new art movement has found its way to a department store," writes Aaron Sheon, "there ought to be no further doubt of its establishment as part of our American daily life, and its ultimate acceptance must be considered only as a question of time". Cubism, far from institutionalized, had become accepted into a wider market, illustrating the reliance of early 20th-century art on massive commercial venues.[11]

Related works

[edit]-

Paul Cézanne, 1890–92, Man with a Pipe (Study for The Card Players), oil on canvas, 39 × 30.2 cm, Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City

-

Paul Cézanne, 1890, Homme à la pipe (Man with a Pipe), oil on canvas, 90 × 72 cm, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg

-

Vincent van Gogh, 1890, Man with a Pipe (Portrait of Dr. Paul Gachet), etching on wove paper, 18.4 × 14.9 cm, Philadelphia Museum of Art

-

Jean Metzinger, 1912, Femme à l'Éventail (Woman with a Fan), oil on canvas, 90.7 × 64.2 cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

-

Albert Gleizes, 1913, Portrait de l’éditeur Eugène Figuière (The Publisher Eugene Figuiere), oil on canvas, 143.5 × 101.5 cm, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon

-

Jean Metzinger, c.1913, Le Fumeur (Man with Pipe), oil on canvas, 129.7 x 96.68 cm, Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Exhibited at the 1914 Salon des Indépendants, Paris

-

Pablo Picasso, 1913–14, L'Homme aux cartes (Card Player), oil on canvas, 108 × 89.5 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York

-

Juan Gris, 1913, El fumador, The Smoker (Frank Haviland), oil on canvas, 73 × 54 cm, Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum

-

Juan Gris, 1912, Portrait Germaine Raynal

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Carlson, Elizabeth. "An Unlikely Exhibition: Cubism Comes to in Milwaukee in 1913", Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Studies Association Annual Meeting, Hyatt Regency, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 16 October 2008

References

[edit]- ^ a b Art Crimes, Art and Antiques Magazine, December 1998, p. 22.

- ^ The Modern Spirit: Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture, 1914. Manierre Dawson papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- ^ Jean Metzinger, Portrait of an American Smoking (Man with a Pipe), 1911–12, oil on canvas, 92.7 x 65.4 cm (36.5 x 25.75 in) Lawrence University, Appleton, Wisconsin

- ^ Jean Metzinger, 1911–12, Man with a Pipe (Portrait of an American Smoking), oil on canvas, 92.7 × 65.4 cm (36.5 × 25.75 in), Lawrence University, Appleton, Wisconsin

- ^ Milwaukee-Downer College, "Snapshot, April 1956" (1956). Milwaukee-Downer College Student Newspapers. Paper 249, p. 3

- ^ IFAR Journal, Volume 2, International Foundation for Art Research, 1998

- ^ Joann Moser, 1985, Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, Cubist Works, 1910–1921, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press. p. 43.

- ^ a b Daniel Robbins, Jean Metzinger, At the Center of Cubism, in Jean Metzinger in Retrospect, 1985, The University of Iowa Museum of Art, J. Paul Getty Trust, University of Washington Press

- ^ Alex Mittelmann, State of the Modern Art World, The Essence of Cubism and its Evolution in Time, 2011

- ^ a b Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Du "Cubisme", published by Eugène Figuière Éditeurs, Paris, 1912, pp. 9-11, 13-14, 17-21, 25-32. In English in Robert L. Herbert, Modern Artists on Art, Englewood Cliffs, 1964, Art Humanities Primary Source Reading 46

- ^ a b c d e f g h "American Studies at the University of Virginia Marketing Modern Art in America: From the Armory Show to the Department Store". Archived from the original on 2013-01-07. Retrieved 2013-07-24.

- ^ Walt Khun, The story of the Armory show, 1938

- ^ Elizabeth Carlson, Cubist Fashion: Mainstreaming Modernism after the Armory, Winterthur Portfolio, Vol. 48, No. 1 (Spring 2014), pp. 1-28. The University of Chicago Press on behalf of the Henry Francis du Pont Winterthur Museum, Inc. Article DOI: 10.1086/675687

- ^ a b New Cubist Pictures. Latest From Paris Fail to Satisfy Art Enthusiasts in Cleveland, O., The Brooklyn Daily Eagle (Brooklyn, New York), Saturday 26 July 1913, p. 4

- ^ Albert Gleizes, Study for Femmes cousant (Women Sewing), Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía. The Kröller-Müller version measures 185.5 x 126 cm