Mallord Street

| |

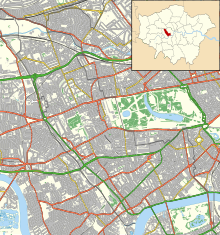

| Location | Chelsea, London, England, United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Postal code | SW3 |

| Nearest metro station | South Kensington tube station |

| Coordinates | 51°29′09″N 0°10′28″W / 51.48586°N 0.17433°W |

| Other | |

| Known for | Edwardian architecture, with several Grade II listed buildings and notable former residents |

Mallord Street is a street in London, England in the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. It was named after Joseph Mallord William Turner who had lived in Chelsea. There are no other streets named Mallord Street in Great Britain.[1]

Mallord Street is parallel to the King's Road and runs from Old Church Street to The Vale. It was created in 1909 when The Vale was extended northwards, and Mallord Street and Mulberry Street were added to link it with Old Church Street.[2] Renumbering took place in 1924.[3]

Nine of the houses in the street are listed Grade II by Historic England[4][5][6][7] and there have been several notable residents, including the author A. A. Milne and the artist Augustus John.

Notable buildings and residents

[edit]Odd-numbered buildings

[edit]No. 1, designed by the architect Ralph Knott, was built in 1911 for watercolourist Cecil Arthur Hunt (1873–1965) who had abandoned a career as a barrister to become a full-time painter.[8] Graham Petrie (1859–1940), a British artist, poster designer and author, lived at 1 Mallord Street from about 1914 up to his tragic death.[9][10] The Hungarian-born, later British, pianist Louis Kentner (1905–1987), who excelled in the works of Chopin and Liszt, lived there from 1946[11][12][13] with his second wife, Griselda Gould, daughter of the pianist Evelyn Suart (Lady Harcourt).

At No. 7, the writer and biographer Enid Moberly Bell (1881–1967), who was the first headmistress at Lady Margaret School in Parsons Green[14] and vice-chair of the Lyceum Club for female artists and writers,[15] set up home with Anne Lupton (1888–1967), the founder and organiser of the London Housing Centre.[14][16] Both women had studied at Newnham College at Cambridge University where Enid graduated with an M.A. in 1911.[14][17] Anne was the sister of Olive Middleton, née Lupton, great-grandmother of Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge.[18] Both Olive and Anne were actively involved in women's issues.

Nos. 9, 11, 13 and 15, all Grade II-listed, are a terrace of four houses, c 1914, by the architect Frederick Ernest Williams (1866–1929).[6][19]

No. 9 was the home of Sir Arthur James Irvine (1909–1978), a British barrister and Labour MP, from the late 1930s.[20][21] In 1939 Irvine, then secretary to the Lord Chief Justice, lived in a flat at No. 17, Tryon House, a residential mansion block.[22]

No. 13 (formerly No. 11) has a blue plaque. It was the home of author A. A. Milne (1882–1956)[23] and his wife Daphne (1890–1971) from 1919 until about 1940. Their son Christopher Robin (1920–1996) was born here. As a child he was the basis of the character Christopher Robin in his father's Winnie-the-Pooh stories and in two books of poems, all written at this house.[24][25]

No. 15 was the home of the actor Dennis Price (1915–1973) from 1948 until his divorce in 1950.[26][27]

No. 19 is Chelsea's former telephone exchange, whose future use is under discussion.[28][29]

At No. 21 (Vale Court) in 1963, Stephen Ward (1912–1963), the society osteopath who was one of the central figures in the Profumo affair, committed suicide in a friend's flat.[30]

Even-numbered buildings

[edit]Nos. 2 and 4, known together as Mallord House, are listed Grade II by Historic England. They were designed by Ralph Knott.[4] The English film and stage actor Garry Marsh was recorded living at "Mallord Cottage" in the 1920s and 1930s.[31]

Nos. 6 and 8, also Grade II listed,[5] were designed by W. D. Caröe in 1912–13 for Percy Morris of Elm Park Gardens, and were originally intended for Morris's coachman.[32]

No. 10 was the home of the Irish sculptor and artist John Francis Kavanagh (1903–1984) from about 1936 to about 1946.[33]

Sir William Thomas Furse (1865–1953), a Master-General of the Ordnance, lived at No. 18.[34]

Anthony Crossley (1903–1939), a writer, publisher and Conservative politician, lived with his family at No. 26.[35]

No. 28 is a house built in 1913–14 by the Russian architect Boris Anrep, from designs by Dutch architect Robert van 't Hoff, for the artist Augustus John (1878–1961) to use as a studio.[36] In 1935 it was bought by the popular singer Gracie Fields (1887–1979).[36] It is a Grade II listed building and has a blue plaque commemorating John.[7][37]

No. 32 was built in about 1913 for the landscape artist Arthur Croft Mitchell (1872–1956), including a studio at the back, from designs by Charles Hall.[37][22] He lived there until his death.[38]

Notes and references

[edit]- ^ "Mallord Street in Chelsea". Streetlist.

- ^ Croot, Patricia E C, ed. (2004). A History of the County of Middlesex: Volume 12, Chelsea. Settlement and building: Artists and Chelsea'. Victoria County History, London. pp. 102–106 – via British History Online.

- ^ "Renumbering Mallord Street". Chelsea News and General Advertiser. 16 May 1924. p. 3.

- ^ a b Historic England (9 March 1982). "Mallord House, 2 and 4, Mallord Street SW3 (1225537)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ a b Historic England (21 October 1994). "6 and 8, Mallord Street SW3 (1265139)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ a b Historic England (21 October 1997). "9–15, Mallord Street SW3 (1031502)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ a b Historic England (9 September 1993). "28, Mallord Street SW3 (1265177)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ Churchill, Penny (13 February 2018). "1, Mallord Street: The ultimate Chelsea pied-à-terre?". Country Life. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "FATAL SMOKING IN BED 81-YEAR-OLD ARTIST'S DEATH". West London Observer. 7 June 1940. p. 1.

- ^ "Mr Graham Petrie". Times. 4 June 1940. p. 9 – via The Times Digital Archive.

- ^ "NATURALIZATION". The London Gazette. 37566: 2297. 14 May 1946 – via The Gazette.

- ^ "Louis Kentner 1 Mallord Street, Chelsea, London". Notable Abodes. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ Andrews, Cyrus (ed.). Radio & Television Who's Who. London: George Young, 3rd edition, 1954

- ^ a b c Housing Review, Volume 17. Housing Centre – University of California. 1968. pp. 3 and 48. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ Doughan, David (ed.); Gordon, Peter (ed.) (2001). Dictionary of British Women's Organisations, 1825–1960 (Woburn Education Series), London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0713002232

- ^ "Miss A. M. Lupton – Organiser of the London Housing Centre". The Yorkshire Post. 15 March 1935.

- ^ "Contemporary Authors: First revision – Volumes 5–8". Gale Research Company. 1969. p. 786. Retrieved 28 October 2017.

MOBERLY-BELL, Enid 1881– PERSONAL: Born March 24, 1881, in Alexandria, Egypt; daughter of Charles Frederic (a journalist) and Ethel (Chataway) Moberly-Bell. Education: Newnham College, Cambridge University, M.A., 1911

- ^ Joseph, Claudia (1990). Kate: The Making of a Princess. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing. ISBN 978-1845-965-778. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "13 Mallord Street: Design and access statement" (PDF). Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. September 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "Mearns Candidate Weds". Dundee Courier. 4 October 1937. p. 5 – via British Library Newspapers.

- ^ "Parliamentary Bye-Election". Aberdeen Journal. 11 May 1939 – via British Library Newspapers.

- ^ a b The National Archives; Kew, London, England; 1939 Register; Reference: RG 101/107A, Enumeration District: AFAL. Ancestry.com

- ^ "Milne, A.A. (1882–1956) Plaque erected in 1979 by Greater London Council at 13 Mallord Street, Chelsea, London, SW3 6DT, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea". English Heritage. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ^ "Milne, A.A. (1882–1956)". Blue Plaques. English Heritage. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "Heritage Statement 13 Mallord Street, Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea" (PDF). Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea. April 2015.

- ^ "Dennis Price Divorced". Gloucester Citizen. 24 October 1950 – via British Library Newspapers.

- ^ Parker, Elaine; Owen, Gareth (2018). The Price of Fame: The Biography of Dennis Price. Fonthill Media.

- ^ "A new school in Mallord Street?". Chelsea Society. May 2019. Retrieved 11 July 2020.

- ^ "19 Mallord Street". Westminster Property Association. 28 June 2019. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ Mangold, Tom (8 December 2013). "Stephen Ward wasn't murdered. I was there". The Independent. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ "THE BANKRUPTCY ACTS". The London Gazette. 33242: 558. 25 January 1927 – via The Gazette.

- ^ Cherry, Bridget; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1991). Buildings of England. London 3: North West. Yale University Press. p. 587.

- ^ "John Francis Kavanagh". Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851–1951 (online database). University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII. 2011. Retrieved 12 July 2020.

- ^ Furse, W. T. (13 April 1939). "Service To The State". The Times. p. 13 – via The Times Digital Archive.

- ^ "Deaths". The Times. 19 August 1939. p. 1 – via The Times Digital Archive.

- ^ a b Lassandro, Sebastian (2019). Pride of Our Alley: The Life of Dame Gracie Fields Volume I; 1898–1939. Albany, Georgia: BearManor Media. ISBN 978-1-62933-420-2.

- ^ a b Architectural History Practice Ltd (February 2013). "Heritage Impact Assessment February 2013 28 Mallord Street, London SW3" (PDF). Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea.

- ^ Probate 1957. Find a will | GOV.UK (probatesearch.service.gov.uk)