Malaysian Malays

Orang Melayu Malaysia ملايو مليسيا | |

|---|---|

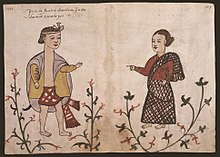

Malay children playing Tarik Upih Pinang, a traditional game that involves dragging a palm frond | |

| Total population | |

| 17,610,458 57.9% of the Malaysian population (2023)[1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Malaysia | |

| Languages | |

| Malayic languages (Numerous vernacular Malay varieties) • Standard Malay • English • Arabic | |

| Religion | |

| Sunni Islam | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

Malaysian Malays (Malay: Orang Melayu Malaysia, Jawi: ملايو مليسيا) are Malaysians of Malay ethnicity whose ancestry originates wholly or partly in the Malay world. According to the 2023 population estimate, with a total population of 17.6 million, Malaysian Malays form 57.9% of Malaysia's demographics, the largest ethnic group in the country. They can be broadly classified into two main categories; Anak Jati (indigenous Malays or local Malays) and Anak Dagang (trading Malays or foreign Malays).[2][3]

The Anak Jati or native Malays consist of those individuals who adhere to the Malay culture native to the coastal areas of Malay Peninsula and Borneo.[3] Among notable groups include the Bruneians, Kedahans, Kelantanese, Pahangite, Perakians, Sarawakians and Terengganuans. On the other hand, the Anak Dagang or foreign Malays, consist of descendants of immigrants from other parts of Malay Archipelago who became the citizens of the Malay sultanates and were absorbed and assimilated into Malay culture at different times, aided by similarity in lifestyle and common religion.

The foreign Malays have Acehnese, Banjarese, Buginese, Javanese, Mandailing and Minangkabau ancestries that come from Indonesia.[4][5] Some foreign Malays may also come from other parts of Southeast Asia, that includes the Chams of Indochina, Cocos Malays of Australian Cocos (Keeling) Islands as well as the Patani Malays of southern Thailand. There is also a minority of Malays who are partially descended from more recent immigrants from many other countries who have assimilated into Malay Muslim culture.

Definition of a Malay

[edit]The identification of Malay with Islam traces its origin to the 15th century, when vigorous ethos of Malay identity was developed and transmitted during the time of the Melaka Sultanate. Common definitive markers of a Malayness are thought to have been promulgated during this era, resulting in the ethnogenesis of the Malay as a major ethnoreligious group in the region. In literature, architecture, culinary traditions, traditional dress, performing arts, martial arts, and royal court traditions, Melaka set a standard that later Malay sultanates emulated.[6][7] Today, the most commonly accepted elements of Malayness – the Malay Rulers, Malay language and culture, and Islam – are institutionalised in both Malay-majority countries, Brunei and Malaysia.[8][9][10][11] As a still fully functioning Malay sultanate, Brunei proclaimed Malay Islamic Monarchy as its national philosophy.[12] In Malaysia, where the sovereignty of individual Malay sultanates and the position of Islam are preserved, a Malay identity is defined in Article 160 of the Constitution of Malaysia.

Article 160 defines a Malay as someone born to a Malaysian citizen who professes to be a Muslim, habitually speaks the Malay language, adheres to Malay customs, and is domiciled in Malaysia, Singapore or Brunei. This definition is perceived by some writers as loose enough to include people of a variety of ethnic backgrounds which basically can be defined as "Malaysian Muslims" and therefore differs from the anthropological understanding of what constitutes an ethnic Malay.[13] However, there exist Muslim communities in Malaysia with distinctive cultures and spoken languages that cannot be categorised constitutionally as Malay. These include Muslim communities that have not fully embraced Malayness, like Tamil Muslims and Chinese Muslims.

This constitutional definition had firmly established the historical Malay ethnoreligious identity in the Malaysian legal system,[13] where it has been suggested that a Malay cannot convert out of Islam as illustrated in the Federal Court decision in the case of Lina Joy.[14] As of the 2023, Malays made up 57.9% of the population of Malaysia (including Malaysian-born or foreign-born people of Malay descent).

History

[edit]

The Malay World, home of the various Malayic Austronesian tribes since the last Ice age (circa 15,000–10,000 BCE), exhibits fascinating ethnic, linguistic and cultural variations.[15] The indigenous animistic belief system, which employed the concept of semangat (spirit) in every natural objects, was predominant among the ancient Malayic tribes before the arrival of Dharmic religions.[16] Deep in the estuary of the Merbok River, lies an abundance of historical relics that have unmasked several ceremonial and religious architectures devoted for the sun and mountain worshiping.[17][18][19] At its zenith, the massive settlement sprawled across a thousand kilometers wide, dominated in the northern plains of the Malay Peninsula.[17][18] On contemporary account, the area is known as the lost city of Sungai Batu. Founded in 535 BC, it is the oldest testament of civilisation in Southeast Asia and a potential progenitor of the Kedah Tua kingdom. In addition to Sungai Batu, the coastal areas of the Malay Peninsula also witnessed the development of other subsequent ancient urban settlements and regional polities, driven by a predominantly cosmopolitan agrarian society, thriving skilled craftsmanship, multinational merchants and foreign expatriates. Chinese records noted the names of Akola, P'an P'an, Tun-Sun, Chieh-ch'a, Ch'ih-tu, Pohuang, Lang-ya-xiu among few. Upon the fifth century AD, these settlements had morphed into a sovereign city-states, collectively fashioned by an active participation in the international trade network and hosting diplomatic embassies from China and India.[17][18] Between the 7th and 13th centuries, many of these small, prosperous peninsula maritime trading states, became part of the mandala of Srivijaya,[20]

The Islamic faith arrived on the shores of the Malay Peninsula from around the 12th century.[21] The earliest archaeological evidence of Islam is the Terengganu Inscription Stone dating from the 14th century.[22] By the 15th century, the Melaka Sultanate, whose hegemony reached over much of the western Malay Archipelago, had become the centre of Islamisation in the east. Islamisation developed an ethnoreligious identity in Melaka with the term 'Melayu' then, begins to appear as interchangeable with Melakans, especially in describing the cultural preferences of the Melakans as against the foreigners.[6] It is generally believed that Malayisation intensified within Strait of Malacca region following the territorial and commercial expansion of the sultanate in the mid 15th century.[23] In 1511, the Melakan capital fell into the hands of Portuguese conquistadors. However, the sultanate remained an institutional prototype: a paradigm of statecraft and a point of cultural reference for successor states like Johor, Perak and Pahang.[24] In the same era, the sultanates of Kedah, Kelantan and Patani dominated the northern part of the Malay Peninsula. Across the South China Sea, the Bruneian Empire became the most powerful polity in Borneo and reached its golden age in the mid-16th century when it controlled land as far south as present day Kuching in Sarawak, north towards the Philippine Archipelago.[25] By the 18th century, Minangkabau and Bugis settlers established the chiefdom of Negeri Sembilan and the sultanate of Selangor respectively.

Historically, Malay states of the peninsula had hostile relations with the Siamese. Melaka herself fought two wars with the Siamese while northern Malay states came intermittently under Siamese dominance for centuries. From 1771, the Kingdom of Siam under the Chakri dynasty annexed both Patani and Kedah. Between 1808 and 1813, the Siamese partitioned Patani into smaller states while carving out Setul, Langu, Kubang Pasu and Perlis from Kedah in 1839.[28][29] In 1786, the island of Penang was leased to East India Company by Kedah in exchange of military assistance against the Siamese. In 1819, the company also acquired Singapore from Johor Empire, later in 1824, Dutch Malacca from the Dutch, and followed by Dindings from Perak by 1874. All these trading posts officially known as Straits Settlements in 1826 and became the crown colony of British Empire in 1867. British intervention in the affairs of Malay states was formalised in 1895, when Malay rulers of Pahang, Selangor, Perak and Negeri Sembilan accepted British Residents and formed the Federated Malay States. In 1909, Kedah, Kelantan, Terengganu and Perlis were handed over by Siam to the British. These states along with Johor, later became known as Unfederated Malay States. During the World War II, all these British possessions and protectorates that collectively known as British Malaya were occupied by the Empire of Japan.

Malay nationalism, which developed in the early 1900s, had a cultural rather than a political character. The discussions on a 'Malay nation' focussed on questions of identity and distinction in terms of customs, religion, and language, rather than politics. The debate surrounding the transition centred on the question of who could be called the real Malay, and the friction led to the emergence of various factions amongst Malay nationalists.[30] The leftists from Kesatuan Melayu Muda were among the earliest who appeared with an ideal of a Republic of Greater Indonesia for a Pan-Malay identity.[31] The version of Malayness brought by this group was largely modelled on the orientalist's concept of Malay race, that transcend the religious boundary and with the absence of the role of monarchy.[32] Another attempt to redefine the Malayness was made by a coalition of left wing political parties, the AMCJA, that proposed the term 'Melayu' as a demonym or citizenship for an independent Malaya. In the wake of the armed rebellion launched by the Malayan Communist Party, the activities of most left wing organizations came to a halt following the declaration of Malayan Emergency in 1948 that witnessed a major purges by the British colonial government.[31] This development left those of moderate and traditionalist faction, with an opportunity to gain their ground in the struggle for Malaya's independence.[33] The conservatives led by United Malays National Organization, that vehemently promoted Malay language, Islam and Malay monarchy as key pillars of Malayness, emerged with popular support not only from general Malay population, but also from the Rulers of the Conference of Rulers. Mass protests from this group against the Malayan Union, a unitary state project, forced the British to accept an alternative federalist order known as the Federation of Malaya.[15] The federation would later be reconstituted as Malaysia in 1963.

Language

[edit]

Malay is the national language, and the most commonly spoken language in Malaysia, where it is estimated that 20 percent of all native speakers of Malay live.[34] The terminology as per federal government policy is Bahasa Malaysia (literally "Malaysian language")[35] but in the federal constitution continues to refer to the official language as Bahasa Melayu (literally "Malay language").[36] The National Language Act 1967 specifies the Latin (Rumi) script as the official script of the national language, but allow the use of the traditional Jawi script.[37] Jawi is still used in the official documents of state Islamic religious departments and councils, on road and building signs, and also taught in primary and religious schools.

Malay is also spoken Brunei, Indonesia, Singapore, Timor Leste as well as Thailand and Australian Cocos and Christmas Islands. The total number of speakers of Standard Malay is about 60 million.[38] There are also about 198 million people who speak Indonesian, which is a form of Malay.[39] Standard Malay differs from Indonesian in a number of ways, the most striking being in terms of vocabulary, pronunciation and spelling. Less obvious differences are present in grammar. The differences are rarely a barrier to effective communication between Indonesian and Malay speakers, but there are certainly enough differences to cause occasional misunderstandings, usually surrounding slang or dialect differences.

The Malay language came into widespread use as the lingua franca of the Melaka sultanate (1402–1511). During this period, the language developed rapidly under the influence of Islamic literature. The development changed the nature of the language with massive infusion of Arabic and Sanskrit vocabularies, called Classical Malay. Under Melaka, the language evolved into a form recognisable to speakers of modern Malay. When the court moved to establish the Johor Sultanate, it continued using the classical language; it has become so associated with Dutch Riau and British Johor that it is often assumed that the Malay of Riau is close to the classical language. However, there is no connection between Melakan Malay as used on Riau and the Riau vernacular.[40]

Variants of Malay in Malaysia differed by states, districts or even villages. The Melaka-Johor dialect, owing to its prominence in the past, became the standard speech among Malays in Brunei, Malaysia and Singapore. There are also well-known variants of Malayan languages that are mostly unintelligible to Standard Malay speakers including Kelantanese, Terengganuan, Pahangite, Kedahan (including Perlisian and Penangite), Perakian, Negeri Sembilanese, Sarawakian, and Bruneian (including a Bruneian-based pidgin Sabah Malay).

Culture

[edit]| Average Malay population of Malaya by state 1911-1947 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Total: 1826307

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Source: Malayan Census[42][43][44] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

In Malaysia, the state's constitution empowered Malay rulers as the head of Islam and Malay customs in their respective state. State councils known as Majlis Agama Islam dan Adat Istiadat Melayu (Council of Islam and Malay Customs) are responsible in advising the rulers as well as regulating both Islamic affairs and Malay adat.[45][46] Legal proceedings on matters related to Islamic affairs and Malay adat are carried out in Syariah Court. There is considerable genetic, linguistic, cultural, and social diversity among the many Malay subgroups as a result of hundreds of years of immigration and assimilation of various regional ethnicity and tribes within Southeast Asia.

Malay cultures trace their origin from the early settlers that consist primarily from both various Malayic speaking Austronesians and various Austroasiatic tribes.[47] Around the opening of the common era, Dharmic religions were introduced to the region, where it flourished with the establishment of many ancient maritime trading states in the coastal areas of the Malay Peninsula and Borneo.[48][49] Much of the cultural identities originating from these ancient states survived among the east coasters (Kelantanese, Terengganuans, Pahangites), northerners (Kedahans and Perakians), and Bornean (Bruneians and Sarawakians).[2]

The traditional culture of Malaysian Malays is largely predominated by the indigenous Malay culture mixed with a variety of foreign influences. As opposed to other regional Malays, the southern Malays (Selangoreans, Negeri Sembilanese, Melakans and Johoreans) display the cultural legacy of the Melaka sultanate. Common definitive markers of Malayness – the religion of Islam, Malay language and Malay adat – are thought to have been promulgated in the region.[50] This region also shows the influences of other parts of the Malay Archipelago due to mass migration during the 17th century. Among the earliest groups were the Minangkabau who had established themselves in Negeri Sembilan, Buginese who had formed the Selangor sultanate and domiciled in large numbers in Johor.

The development of many Malay Muslim-dominated centres in the region drew many of the non-Malay indigenous people like the Dayak, Orang Asli and Orang laut, to embrace Malayness by converting to Islam, emulating the Malay speech and their dress.[51] Throughout their history, the Malays have been known as a coastal-trading community with fluid cultural characteristics.[52][53] They absorbed, shared and transmitted numerous cultural features of other foreign ethnic groups. The cultural fusion between local Malay culture and other foreign cultures also led to the ethnocultural development of the related Arab Peranakan, Baba Nyonya, Chetti Melaka, Jawi Pekan, Kristang, Sam-sam and Punjabi Peranakan cultures.[54]

Today, some Malays have recent forebears from other parts of maritime Southeast Asia, termed as anak dagang ("traders") or foreign Malays who have assimilated into the Malay culture. Other significant population of foreign Malays also includes Acehnese in Kedah, Banjarese and Mandailing in Perak, Chams and Patani Malays in Kelantan and Terengganu as well as Cocos Malays in Sabah. Between the 19th century and the early 20th century, a significant number of immigrants from Java and Sumatra came as traders, settlers and indenture labours to Malaya. British census from 1911 to 1931 shows that many of the immigrants concentrated on the west coast of the Malay Peninsula and largely predominated by ethnic Javanese.[55] The process of adaptation and assimilation carried out by these ethnicities later gave birth to new Malay communities that retain a close relationship with their cultural roots in Java and Sumatra until today.[56]

In 1971, the government created a "National Culture Policy", defining Malaysian culture. The three principles of the National Culture Policy are; Malaysian culture must be based on the indigenous culture of the region, that is the Malay culture, secondly it may incorporate suitable elements from other cultures, and lastly that Islam must play a part in it.[57] Much of Malaysian culture shows heavy influences from Malay culture, an example can be seen in the belief system, whereby the practice of Keramat shrine worshipping that prevalent among Malaysian Chinese, originates from the Malay culture. Other Malay cultural influence can also be seen in traditional dress, cuisine, literature, music, arts and architecture. Traditional Malay dress varies between different regions but the most popular dress in modern-day are Baju Kurung and Baju Kebaya (for women) and Baju Melayu (for men), which all recognised as the national dress of Malaysia.[58]

Many other Malay cultural heritage, are considered as Malaysian national heritage including Mak Yong, Dondang Sayang, Silat, Pantun, Songket, Mek Mulung, Kris, Wayang Kulit, Batik, Pinas and Gamelan.[59] The classical Malay literature tradition that flourished since the 15th century and various genres of Malay folklore also forms the basis of the modern Malaysian literature and folklore. The Malaysian music scene also witnessed strong influence from the Malay traditional music. One particularly important was the emergence of Irama Malaysia ('Malaysian beat'), a type of Malaysian pop music that combined Malay social dance and syncretic music such as Asli, Inang, Joget, Zapin, Ghazal, Bongai, Dikir Barat, Boria, Keroncong and Rodat.[60]

Demographics

[edit]Malaysia

[edit]Malays are the majority of the ethnic groups in Malaysia. Every state has a population of Malays ranging from around 40% to over 90%, except for Sabah and Sarawak which are the only states where Malays are less than 30%. Figures given below are from the 2023 census, and 2020 numbers. The population figures are also given as percentages of the total state population that includes non-citizens.

| State | Population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2023[61] | 2020[61] | |||

| Johor | 2,232,586 | 59.3% | 2,158,943 | 58.5% |

| Kedah | 1,680,759 | 80.5% | 1,624,366 | 79.7% |

| Kelantan | 1,735,521 | 95.5% | 1,671,097 | 95.1% |

| Kuala Lumpur | 846,564 | 47.4% | 824,770 | 46.5% |

| Labuan | 35,302 | 40.3% | 23,604 | 28.0% |

| Malacca | 676,657 | 71.4% | 653,817 | 70.5% |

| Negeri Sembilan | 719,965 | 62.2% | 692,906 | 61.2% |

| Pahang | 1,174,143 | 75.6% | 1,134,900 | 75.0% |

| Perak | 1,408,982 | 58.7% | 1,359,760 | 57.7% |

| Penang | 727,733 | 45.1% | 707,155 | 44.2% |

| Perlis | 250,826 | 88.6% | 245,358 | 88.1% |

| Putrajaya | 110,400 | 96.0% | 101,824 | 95.7% |

| Sabah | 320,760 | 12.0% | 237,355 | 9.1% |

| Sarawak | 597,744 | 25.2% | 575,114 | 24.7% |

| Selangor | 3,955,601 | 60.1% | 3,806,796 | 59.2% |

| Terengganu | 1,144,450 | 97.4% | 1,090,433 | 97.1% |

| Malaysia total | 17,610,458 | 57.9% | 16,901,578 | 56.8% |

Diaspora

[edit]There is a community of Malaysian Malays who make up 20% of the total population of the Australian external territory of Christmas Island.[62]

Anak Jati subgroups

[edit]The Anak Jati groups consist of all Malay subgroups native to the Malay Peninsula and coastal areas of Sabah and Sarawak. The following are among the major subgroups:

| Ethnic group | Language | Native areas | Region |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bruneian Malays | Brunei Malay | Sarawak (Miri, Lawas and Limbang), Sabah (Sipitang, Beaufort, Kuala Penyu, Papar, Kota Kinabalu), Labuan | Coastal Borneo |

| Johorean Malays | Johor Malay | Johor, southern Pahang (Rompin), southern Malacca (Jasin), southern Negeri Sembilan (Tampin) | Southern Malay Peninsula |

| Kedahan Malays | Kedah Malay | Kedah, Perlis, Penang and northern Perak | Northern Malay Peninsula |

| Kelantanese Malays | Kelantan-Pattani Malay | Kelantan and significant populations in Southern Thailand, Gerik district of Perak and Besut district of Terengganu | East Coast of the Malay Peninsula |

| Pahang Malays | Pahang Malay | Pahang | East Coast of the Malay Peninsula |

| Perakian Malays | Perak Malay | Perak | Northern Malay Peninsula |

| Sarawak Malays | Sarawak Malay | Sarawak | Coastal Borneo |

| Selangorian Malays | Selangor Malay | Selangor | Central/West Coast of the Malay Peninsula |

| Terengganuan Malays | Terengganu Malay | Terengganu and significant populations in Johor (Mersing) and Pahang (Kuantan and Rompin) | East Coast of the Malay Peninsula |

Anak Dagang subgroups

[edit]Other than the Anak Jati or indigenous Malays, there are Malay communities in Malaysia with full or partial ancestry of other ethnicities of Maritime Southeast Asia. The communities, collectively termed as Anak Dagang or traders or foreign Malays, are descendants of immigrants from various ethnicities like Acehnese, Banjarese, Boyanese, Bugis, Chams, Javanese, Minangkabaus, and Tausugs who have effectively assimilated into the local Malay culture.[63][64]

From the 17th century, Bugis mercenaries and merchants involved in both commercial and political ventures in the Malay sultanates, later establishing their main settlements along Klang and Selangor estuaries. Another case of in-movements was the migration of Minangkabau peoples to Negeri Sembilan. The resulting intermarriages between the Minangkabau immigrants and the native Proto-Malay Temuan peoples, gave birth to a Malay community in Negeri Sembilan that adopted extensively the indigenous customary law or Adat Benar and traditional political organization.[65] Apart from being described as bilateral in nature, the earlier movements of peoples involving the Malay Peninsula, can be described as small in extent, with no other evidence of mass migration that caused significant demographic change.[66]

In the 19th century, the growth in arrivals of Indonesians coincided with the consolidation of British influence in Malaya.[67] This was a period of extensive economic growth which saw economic centres in the Straits Settlements and their neighbouring West Coast States of central and southern Malaya, became the main destination of immigrants.[68] In 1824, the Indonesian immigrant population began to be enumerated for the first time by the British administration in the Straits Settlements.[69] By 1871, the Indonesian population in the Straits Settlements was recorded at 12,143, mostly can be found in Singapore, with Javanese was the most numerous ethnicity.[70] Despite this, the Indonesian population was considerably small, and their growth was slow compared to their Chinese counterparts.[68] In 1891, the census area began to be extended to the Federated Malay States and recorded a total of 20,307 Indonesians.[71] At the same time, the state of Johor under Temenggong Daeng Ibrahim (1841–1855) encouraged the migration of estate labourers from Java to work in the agricultural sector of the state.[72] Such policy was continued under the rule of his son, Abu Bakar. As a result, in the first Malayan-wide census in 1911, Johor recorded the largest Indonesian population, 37,000[73] from overall 117,600 Indonesians in Malaya.[74]

Between 1911 and 1957 censuses, the Indonesian population in Malaya stood between 8.6% to 14.5% of total number of Malays,[75] numerically inferior to those native peninsula Malays in the north and eastern states.[76] In individual States during the 1911—1957 period, the Indonesian population had exceeded 50% of the total Malays only in 1931, in Johor.[76] After 1957, due to stricter government controls on the movements of Indonesians into Malaya, it is most unlikely to see similar immigration pattern in the past in Malaya.[77] Because of their relatively small population and their close and strong cultural and ethnic relationships with the indigenous Malays, within decades, most of these Indonesian immigrants were effectively assimilated into the Malay identity.[63][64][78]

In more recent times, during the Vietnam War, a sizable number of Chams migrated to Peninsular Malaysia, where they were granted sanctuary by the Malaysian government out of sympathy for fellow Muslims; most of them have also assimilated with the Malay cultures.[79]

| State | Malaya: Percentage of Indonesians in total Malay population,[80] 1911-1957[75] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1911 | 1921 | 1931 | 1947 | 1957 | |

| Singapore | 42.4 | 39.9 | 42.1 | 38.2 | 31.7 |

| Penang | 4.5 | 3.1 | 2.4 | 2.2 | 1.7 |

| Malacca | 4.0 | 3.2 | 3.3 | 4.5 | 3.6 |

| Perak | 16.6 | 18.8 | 21.4 | 17.1 | 10.5 |

| Selangor | 27.3 | 28.4 | 45.6 | 43.9 | 32.3 |

| Negeri Sembilan | 4.5 | 3.9 | 6.5 | 5.9 | 4.7 |

| Pahang | 1.2 | 4.2 | 5.8 | 3.0 | 2.6 |

| Johor | 34.2 | 42.5 | 51.5 | 31.5 | 25.6 |

| Kedah | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.1 |

| Kelantan | 0.01 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Terengganu | 0.02 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Perlis | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| Malaya | 8.6% | 10.8% | 14.5% | 12.3% | 8.7% |

Genetics

[edit]Studies on the genetics of modern Malays show a complex history of admixture of human populations. The analyses reveal that the Malays are genetically diverse, and that there are substantial variations between different populations of Malays. The differences may have arisen from geographical isolation and independent admixture that occurred over a long period. The studies indicate that there is no single representative genetic component, rather there are four major ancestral components to the Malay people: Austronesian aborigines, Proto-Malay, East Asian, and South Asian, with the Austronesian and Proto-Malay components comprising 60–70% of the genome.[81] The Austronesian component is related to the Taiwanese Ami and Atayal people, and genetic analyses of the Austronesian component in Southeast Asians may lend support to the "Out of Taiwan" hypothesis, although some suggest that it is largely indigenous with a smaller contribution from Taiwan.[82][83] The Proto-Malays such as the Temuan people show genetic evidence of having moved out of Yunnan, China, thought to be about 4,000–6,000 years ago.[84] The admixture events with South Asians (Indians) may have been ancient (estimate of up to 2,250 years ago in some Indonesian Malays), while the admixture events with East Asians (Chinese) may be more recent (100–200 years ago),[81] although some may have occurred before the 15th century in Java.[84] There are also minor components contributed by other groups such as the Negritos (the earliest inhabitants of the Malay Peninsula), Central Asians and Europeans. Most of the admixture events are estimated to have occurred 175 to 1,500 years ago.[81]

Within the Malay Peninsula itself, the Malays are differentiated genetically into distinct clusters between the northern part of the Malay Peninsula and the south.[85] SNP analyses of five of their sub-ethnic groups show that Melayu Kelantan and Melayu Kedah (both in the northern Malay Peninsula) are closely related to each other as well as to Melayu Patani, but are distinct from Melayu Minang (western), Melayu Jawa and Melayu Bugis (both southern).[86] The Melayu Minang, Melayu Jawa and Melayu Bugis people show close relationship with the people of Indonesia, evidence of their shared common ancestry with these people.[84] However, Melayu Minang are closer genetically to Melayu Kelantan and Melayu Kedah than they are to Melayu Jawa. Among the Melayu Kelantan and Melayu Kedah populations, there are significant Indian components, in particular from the Telugus and Marathis. The Melayu Kedah and Melayu Kelantan also have closer genetic relationship to the two subgroups of the Orang Asli Semang, Jahai and Kensiu, than other Malay groups. Four of the Malay sub-ethnic groups in this study (the exception being Melayu Bugis, who are related to the people of Sulawesi, Indonesia) also show genetic similarity to the Proto-Malay Temuan people with possible admixture to the Jawa populations and the Wa people of Yunnan, China.[86]

See also

[edit]- Bruneian Malays

- Patani Malays

- Malay Singaporean

- Cocos Malays

- Malay Indonesian

- Sama-Bajau

- Tausūg people

- Dayak people

References

[edit]- ^ "Demographic Statistics Malaysia - First Quarter of 2023" (PDF). Department of Statistics, Malaysia. 2023. Retrieved 25 May 2023.

- ^ a b Mohd Hazmi Mohd Rosli; Rahmat Mohamad (5 June 2014). "Were the Malays immigrants?". The Malay Mail Online. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ a b Miller & Williams 2006, pp. 45–46

- ^ Gulrose Karim 1990, p. 74

- ^ Suad Joseph & Afsaneh Najmabadi 2006, p. 436

- ^ a b Barnard 2004, p. 4

- ^ Milner 2010, p. 230

- ^ Azlan Tajuddin (2012), Malaysia in the World Economy (1824–2011): Capitalism, Ethnic Divisions, and "Managed" Democracy, Lexington Books, p. 94, ISBN 978-0-7391-7196-7

- ^ Khoo, Boo Teik; Loh, Francis (2001), Democracy in Malaysia: Discourses and Practices (Democracy in Asia), Routledge, p. 28, ISBN 978-0-7007-1161-1

- ^ Chong, Terence (2008), Globalization and Its Counter-forces in Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, p. 60, ISBN 978-981-230-478-0

- ^ Hefner, Robert W. (2001), Politics of Multiculturalism: Pluralism and Citizenship in Malaysia, Singapore, and Indonesia, University of Hawaii Press, p. 184, ISBN 978-0-8248-2487-7

- ^ Benjamin, Geoffrey; Chou, Cynthia (2002), Tribal Communities in the Malay World: Historical, Cultural and Social Perspectives, London: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, p. 55, ISBN 978-981-230-166-6

- ^ a b Frith, T. (1 September 2000). "Ethno-Religious Identity and Urban Malays in Malaysia". Asian Ethnicity. 1 (2). Routledge: 117–129. doi:10.1080/713611705. S2CID 143809013.

- ^ "Federal Court rejects Lina's appeal in a majority decision". The Star. Kuala Lumpur. 31 May 2007. Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 23 February 2008.

- ^ a b Hood Salleh 2011, p. 28

- ^ Ragman 2003, pp. 1–6

- ^ a b c Pearson 2015[page needed]

- ^ a b c Hall 2017, p. 111

- ^ Mok, Opalyn (9 June 2017). "Archaeologists search for a king in Sungai Batu". The Malay Mail Online. Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ Sabrizain (2006). "Early Malay kingdoms". Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ Hussin Mutalib 2008, p. 25

- ^ UNESCO (2001). "Batu Bersurat Terengganu (Inscribed Stone of Terengganu)". Retrieved 6 March 2018.

- ^ Andaya 2008, p. 200

- ^ Harper 2001, p. 15

- ^ Richmond 2007, p. 32

- ^ Tan 1988, p. 14

- ^ Chew 1999, p. 78

- ^ Andaya & Andaya 1984, pp. 62–68

- ^ Ganguly 1997, p. 204

- ^ Hood Salleh 2011, p. 29

- ^ a b Blackburn & Hack 2012, pp. 224–225

- ^ Barrington 2006, pp. 47–48

- ^ Blackburn & Hack 2012, p. 227

- ^ Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D. (2018). "Malay: A language of Malaysia". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Twenty-first edition. SIL International. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ "Mahathir regrets govt focussing too much on Bahasa". Daily Express. 2 October 2013. Archived from the original on 12 July 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2013.

- ^ "Federal Constitution" (PDF). Judicial Appointments Commission. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 March 2012. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ "National Language Act 1967" (PDF). Malaysian Attorney General Chambers. 2006. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 August 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2015.

- ^ Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D. (2018). "Malay: A macrolanguage of Malaysia". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Twenty-first edition. SIL International. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ Simons, Gary F.; Fennig, Charles D. (2018). "Indonesian: A language of Indonesia". Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Twenty-first edition. SIL International. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ Sneddon, James N. (2003). The Indonesian Language: Its History and Role in Modern Society. UNSW Press. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-86840-598-8.

- ^ Colonial census used the term "Other Malaysians" to refer to other natives of Malay Archipelago or the "foreign Malays". From 1957 onwards, all these different ethnicities were grouped into a single "Malay" category

- ^ Bahrin 1967, p. 286

- ^ Tan 1982, p. 37

- ^ "Census population by state, Peninsular Malaysia, 1901–2010" (PDF). Economic History of Malaya: Asia-Europe Institute, University of Malaya. 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ Peletz 1992, p. 119

- ^ Amineh Mehdi Parvizi 2010, pp. 96–97

- ^ Farish A Noor 2011, pp. 15–16

- ^ Milner 2010, pp. 24, 33

- ^ Barnard 2004, p. 7&60

- ^ Melayu Online 2005.

- ^ Andaya & Andaya 1984, p. 50

- ^ Milner 2010, p. 131

- ^ Barnard 2004, pp. 7, 32, 33 & 43

- ^ Gill, Sarjit S. (2001). "Perkahwinan Campur Peranakan Punjabi di Sabah" (PDF). Sari 19: 189–203 – via journalarticle.ukm.my.

- ^ Bahrin 1967, pp. 272–280

- ^ Linda Sunarti 2017, pp. 225–230

- ^ "National Culture Policy". www.jkkn.gov.my. National Department for Culture and Arts: Ministry of Tourism and Culture. 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ Condra 2013, p. 465

- ^ "Objek Warisan Tidak Ketara (Intangible Cultural Heritage)". www.heritage.gov.my. Department of National Heritage: Ministry of Tourism and Culture. 2018. Retrieved 11 March 2018.

- ^ Matusky & Tan 2004, p. 383

- ^ a b "2023 Population and Housing Census of Malaysia" (PDF).

- ^ Simone Dennis (2008). Christmas Island: An Anthropological Study. Cambria Press. pp. 91–. ISBN 978-1-60497-510-9.

- ^ a b Milner 2010, p. 232.

- ^ a b Linda Sunarti 2017, pp. 225–230.

- ^ Nerawi Sedu, Nurazzura Mohamad Diah & Fauziah Fathil 2019, pp. 143–167.

- ^ Bahrin 1967, p. 297.

- ^ Bahrin 1967, p. 282.

- ^ a b Bahrin 1967, p. 284.

- ^ Bahrin 1967, p. 269.

- ^ Bahrin 1967, p. 270.

- ^ Bahrin 1967, p. 271.

- ^ Bahrin 1967, p. 283.

- ^ Bahrin 1967, p. 274.

- ^ Bahrin 1967, p. 273.

- ^ a b Bahrin 1967, p. 286.

- ^ a b Bahrin 1967, p. 285.

- ^ Bahrin 1967, p. 279.

- ^ Bahrin 1967, p. 267.

- ^ Juergensmeyer & Roof 2011, p. 1210.

- ^ Colonial census used the term "Malaysians" as an umbrella term for all natives of Malay Archipelago, while their ethnicities being enumerated separately. From 1957 onwards, all these different ethnicities were grouped into a single "Malay" category

- ^ a b c Lian Deng; Boon-Peng Hoh; Dongsheng Lu; Woei-Yuh Saw; Rick Twee-Hee Ong; Anuradhani Kasturiratne; H. Janaka de Silva; Bin Alwi Zilfalil; Norihiro Kato; Ananda R. Wickremasinghe; Yik-Ying Teo; Shuhua Xu (3 September 2015). "Dissecting the genetic structure and admixture of four geographical Malay populations". Scientific Reports. 5: 14375. Bibcode:2015NatSR...514375D. doi:10.1038/srep14375. PMC 585825. PMID 26395220.

- ^ Albert Min-Shan Ko; Chung-Yu Chen; Qiaomei Fu; Frederick Delfin; Mingkun Li; Hung-Lin Chiu; Mark Stoneking; Ying-Chin Ko (6 March 2014). "Early Austronesians: into and out of Taiwan". American Journal of Human Genetics. 94 (3): 426–436. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.02.003. PMC 3951936. PMID 24607387.

- ^ Pedro A. Soares; Jean A. Trejaut; Teresa Rito; Bruno Cavadas; Catherine Hill; Ken Khong Eng; Maru MorminaAndreia Brandão; Ross M. Fraser; Tse-Yi Wang; Jun-Hun Loo; Christopher Snell; Tsang-Ming Ko; António Amorim; Maria Pala; Vincent Macaulay; David Bulbeck; James F. Wilson; Leonor Gusmão; Luísa Pereira; Stephen Oppenheimer; Marie Lin; Martin B. Richard (2016). "Resolving the ancestry of Austronesian-speaking populations". Human Genetics. 135 (3): 309–326. doi:10.1007/s00439-015-1620-z. PMC 4757630. PMID 26781090.

- ^ a b c Wan Isa Hatin; Ab Rajab Nur-Shafawati; Mohd-Khairi Zahri; Shuhua Xu; Li Jin; Soon-Guan Tan; Mohammed Rizman-Idid; Bin Alwi Zilfalil; et al. (The HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium) (5 April 2011). "Population Genetic Structure of Peninsular Malaysia Malay Sub-Ethnic Groups". PLOS ONE. 6 (4): e18312. Bibcode:2011PLoSO...618312H. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018312. PMC 3071720. PMID 21483678.

- ^ Boon-Peng Hoh; Lian Deng; Mat Jusoh Julia-Ashazila; Zakaria Zuraihan; Ma'amor Nur-Hasnah; Ab Rajab Nur-Shafawati; Wan Isa Hatin; Ismail Endom; Bin Alwi Zilfalil; Yusoff Khalid; Shuhua Xu (22 July 2015). "Fine-scale population structure of Malays in Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore and implications for association studies". Human Genomics. 9 (1): 16. doi:10.1186/s40246-015-0039-x. PMC 4509480. PMID 26194999.

- ^ a b Wan Isa Hatin; Ab Rajab Nur-Shafawati; Ali Etemad; Wenfei Jin; Pengfei Qin; Shuhua Xu; Li Jin; Soon-Guan Tan; Pornprot Limprasert; Merican Amir Feisal; Mohammed Rizman-Idid; Bin Alwi Zilfalil; et al. (The HUGO Pan-Asian SNP Consortium) (2014). "A genome wide pattern of population structure and admixture in peninsular Malaysia Malays". The HUGO Journal. 8 (1). 5. doi:10.1186/s11568-014-0005-z. PMC 4685157. PMID 27090253.

Bibliography

[edit]- Andaya, Leonard Y. (2008), Leaves of the Same Tree: Trade and Ethnicity in the Straits of Melaka, University of Hawaii press, ISBN 978-0-8248-3189-9

- Andaya, Barbara Watson; Andaya, Leonard Yuzon (1984), A History of Malaysia, London: Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 978-0-333-27672-3

- Amineh Mehdi Parvizi (2010), State, Society and International Relations in Asia, Amsterdam University Press, ISBN 978-90-5356-794-4

- Bahrin, Tengku Shamsul (1967), "The growth and distribution of the Indonesian population in Malaya", Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, 123 (2): 267–286, doi:10.1163/22134379-90002906

- Barrington, Lowell (2006), After Independence: Making and Protecting the Nation in Postcolonial and Postcommunist States, University of Michigan press, ISBN 978-0-472-06898-2

- Barnard, Timothy P. (2004), Contesting Malayness: Malay identity across boundaries, Singapore: Singapore University press, ISBN 978-9971-69-279-7

- Blackburn, Kevin; Hack, Karl (2012), War, Memory and the Making of Modern Malaysia and Singapore, National University of Singapore, ISBN 978-9971-69-599-6

- Chew, Melanie (1999), The Presidential Notes: A biography of President Yusof bin Ishak, Singapore: SNP Publications, ISBN 978-981-4032-48-3

- Condra, Jill (2013), Encyclopedia of National Dress: Traditional Clothing around the World, ABC-CLIO, ASIN B00ODJN4WA

- Farish A Noor (2011), From Inderapura to Darul Makmur, A Deconstructive History of Pahang, Silverfish Books, ISBN 978-983-3221-30-1

- Ganguly, Šumit (1997), Government Policies and Ethnic Relations in Asia and the Pacific, MIT press, ISBN 978-0-262-52245-8

- Gulrose Karim (1990). Information Malaysia 1990–91 Yearbook. Kuala Lumpur: Berita Publishing Sdn. Bhd. p. 74.

- Hall, Thomas D. (2017), Comparing Globalizations Historical and World-Systems Approaches, Springer International Publishing, ISBN 978-331-9682-18-1

- Harper, Timothy Norman (2001), The End of Empire and the Making of Malaya, London: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-00465-7

- Hood Salleh (2011), The Encyclopedia of Malaysia, vol. 12 - Peoples and Traditions, Editions Didier Millet, ISBN 978-981-3018-53-2

- Hussin Mutalib (2008), Islam in Southeast Asia, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-981-230-758-3

- Juergensmeyer, Mark; Roof, Wade Clark (2011). Encyclopedia of Global Religion. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-1-4522-6656-5.

- Melayu Online.com's Theoretical Framework, 2005, archived from the original on 21 October 2012, retrieved 4 February 2012

- Matusky, Patricia Ann; Tan, Sooi Beng (2004), The Music of Malaysia: The Classical, Folk and Syncretic Traditions, Routledge, ISBN 978-075-4608-31-8

- Linda Sunarti (2017). "Formation of Javanese Malay identities in Malay Peninsula between the 19th and 20th centuries". Cultural Dynamics in a Globalized World: Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Research in Social Sciences and Humanities. Routledge: 225–230. doi:10.1201/9781315225340-32. ISBN 978-113-8626-64-5.

- Miller, Terry E.; Williams, Sean (2006), Other Malays: Nationalism and Cosmopolitanism in the Modern Malay World, University of Hawaii Press, ISBN 978-997-1693-34-3

- Milner, Anthony (2010), The Malays (The Peoples of South-East Asia and the Pacific), Wiley-Blackwell, ISBN 978-1-4443-3903-1

- Pearson, Michael (2015), Trade, Circulation, and Flow in the Indian Ocean World, Palgrave Series in Indian Ocean World Studies, ISBN 978-113-7564-88-7

- Nerawi Sedu; Nurazzura Mohamad Diah; Fauziah Fathil (2019), Being Human: Responding to Changes, Singapore: Partridge Publishing Singapore, ISBN 978-154-3749-13-7

- Peletz, Michæl Gates (1992), A Share of the Harvest: Kinship, Property and Social History Among the Malays of Rembau, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-08086-7

- Ragman, Zaki (2003), Gateway to Malay culture, Asiapac Books Pte Ltd, ISBN 978-981-229-326-8

- Richmond, Simon (2007), Malaysia, Singapore & Brunei, Lonely Planet publications, ISBN 978-1-74059-708-1

- Suad Joseph; Afsaneh Najmabadi (2006). Economics, Education, Mobility And Space (Encyclopedia of women & Islamic cultures). Brill Academic Publishers. p. 436. ISBN 978-90-04-12820-0.

- Tan, Liok Ee (1988), The Rhetoric of Bangsa and Minzu, Monash Asia Institute, ISBN 978-0-86746-909-7

- Tan, Loong Hoe (1982), The state and economic distribution in Peninsular Malaysia: toward an alternative theoretical approach, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, ISBN 978-997-1902-44-5

Further reading

[edit]- Cummings, William (1998). "The Melaka Malay Diaspora in Makassar c.1500-1669". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 71 (1): 107–121.

- Haji Bagenda Ali (2019), Awal Mula Muslim Di Bali Kampung Loloan Jembrana Sebuah Entitas Kuno, Deepublish, ISBN 978-623-7022-61-9

- Reid, Anthony (2006), Verandah of Violence: The Background to the Aceh Problem, NUS Press, ISBN 978-9971-693-31-2

- Reid, Anthony (2009), Imperial Alchemy: Nationalism and Political Identity in Southeast Asia, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-052-1872-37-9