Christ in Majesty

Christ in Majesty or Christ in Glory (Latin: Maiestas Domini)[1] is the Western Christian image of Christ seated on a throne as ruler of the world, always seen frontally in the centre of the composition, and often flanked by other sacred figures, whose membership changes over time and according to the context. The image develops from Early Christian art, as a depiction of the Heavenly throne as described in 1 Enoch, Daniel 7, and The Apocalypse of John. In the Byzantine world, the image developed slightly differently into the half-length Christ Pantocrator, "Christ, Ruler of All", a usually unaccompanied figure, and the Deesis, where a full-length enthroned Christ is entreated by Mary and St. John the Baptist, and often other figures. In the West, the evolving composition remains very consistent within each period until the Renaissance, and then remains important until the end of the Baroque, in which the image is ordinarily transported to the sky.

Development

[edit]

From the latter part of the fourth century, a still beardless Christ begins to be depicted seated on a throne on a dais, often with his feet on a low stool and usually flanked by Saints Peter and Paul, and in a larger composition the other apostles. The central group of the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus of 359 (Vatican) is the earliest example with a clear date. In some cases Christ hands a scroll to Saint Peter on his right, imitating a gesture often made by Emperors handing an Imperial decree or letter of appointment to an official, as in ivory consular diptychs, on the Arch of Constantine, and the Missorium of Theodosius I. This depiction is known as the Traditio legis ("handing over the law"), or Christ the lawgiver – "the apostles are indeed officials, to whom the whole world is entrusted" wrote Saint John Chrysostom.[3] This depiction tends to merge into one of "Christ the teacher", which also derives from classical images of bearded philosophers.

Other Imperial depictions of Christ, standing as a triumphing general, or seated on a ball representing the world, or with different companions, are found in the next centuries. By the seventh century the Byzantine Christ Pantocrator holding a book representing the Gospels and raising his right hand has become essentially fixed in the form it retains in Eastern Orthodoxy today.[4] "Christ Triumphant" had a separate future development, usually standing, often with both hands raised high.

The Pantocrator figure first became half-length because large versions filled the semi-dome of the apse of many, if not most, decorated churches. A full-length figure would need to be greatly reduced for the head to make maximum impact from a distance (because of the flattening at the top of the semi-dome). The gesture Christ makes has become one of blessing, but is originally an orators gesture of his right to speak.[5] The Deesis became standard at the centre of the templon beam in Orthodox churches and the templon's successor, the iconostasis, and is also found as a panel icon. Generally the Pantocrator has no visible throne, but the earlier Deesis does, and at least a single-step dais. The Deesis continues to appear in Western art, but not as often or in such an invariable composition as in the East.

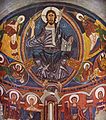

In the West the image showed a full-length enthroned Christ, often in a mandorla or other geometrical frame, surrounded by the symbols of the Four Evangelists, representing the vision of Chapters 4 and 5 of the Book of Revelation. In the Romanesque period the twenty-four elders of the Apocalypse are often seen. Christ also holds a book and makes the blessing gesture, no doubt under Byzantine influence. In both, Christ's head is surrounded by a crossed halo. In Early Medieval Western art the image was very often given a full page in illuminated Gospel Books, and in metalwork or ivory on their covers, and it remained very common as a large-scale fresco in the semi-dome of the apse in Romanesque churches, and carved in the tympanum of church portals. This "seems to have been almost the only theme of apse-pictures" in Carolingian and Ottonian churches, all of which are now lost, although many examples from the period survive in illuminated manuscripts.[6]

From the Romanesque period, the image in the West often began to revert to the earliest, more crowded conception, and archangels, apostles and saints, now often all facing inwards towards Christ, appear, as well as the beasts emblematic of the Evangelists and the twenty-four elders. This development paralleled the movement towards a more "realistic" depiction of the "heavenly court" seen in the increasingly popular subjects of the Maestà (the enthroned Virgin and Child) and the Coronation of the Virgin by Christ.

A Christ in Majesty became standard carved in the tympanum of a decorated Gothic church portal, by now surrounded by a large number of much smaller figures around the archivolts. In painting, the Ghent Altarpiece is the culmination of the Gothic image, although a minority of art historians believe that in this case it is God the Father, not Christ, who is shown in majesty.

Christ in Judgement

[edit]

A variant figure, or the same figure in a different context termed Christ in Judgement, depicting Christ as judge, became common in Last Judgements, often painted on the west (rear) wall of churches. Here an enthroned Christ, from the 13th century usually with robes pulled aside above the waist to reveal the wounds of the Passion (a motif taken from images of the Doubting Thomas[7]) sits high in a complex composition, with sinners being dragged down by devils to Hell on the right and the righteous on the left (at Christ's right-hand side) rising up to Heaven. Generally Christ still looks straight forward at the viewer, but has no book; he often gestures with his hands to direct the damned downwards, and the saved up.[8]

From the High Renaissance the subject was more loosely treated; Christ and his court take to the clouds, and are distributed with an eye to a harmonious and "natural" composition rather than the serried ranks of old. From the late Renaissance and through the Baroque, it often forms the upper part of a picture depicting events on earth in the lower register, and as stricter perspective replaces the hieratic scaling of the Middle Ages, Christ becomes literally diminished. Such depictions tend not to be described as "Christ in Majesty", although they are the linear development of the earlier image; the main subject has become the human events in the foreground, such as the martyrdom of a saint, to which Christ is now a rather distant witness.

Gallery

[edit]-

Roman mosaic with a traditio Legis scene, from the basilica Santa Costanza, Rome, 4th century

-

Old reproduction of the Sarcophagus of Junius Bassus, with a Traditio Legis

-

Christ in Majesty, in a mandorla and surrounded by the tetramorph, Romanesque fresco, apse of Sant Climent de Taüll, Catalonia, 1123

-

Christ in Majesty with the symbols of the Evangelists, stone relief, south portal, Benedictine monastery at Innichen, South Tyrol

-

The Last Judgement by Fra Angelico, 1425–1431

-

Christ in Majesty from Godescalc Evangelistary

-

Maiestas Domini page from Codex Amiatinus (fol. 796v), Firenze, Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana

-

Font by the Scandinavian Master Majestatis, most of whose identifiable work is of the subject

-

Crucifix with Christ in Majesty; anonymous; 12th century

-

The tympanum at Westminster Cathedral showing Christ in Majesty with the Virgin Mary and Saints; a mosaic by Robert Anning Bell after drawings by John Francis Bentley, 1916

-

Christ in Glory depicted on a large tapestry in Coventry Cathedral, designed by Graham Sutherland and completed in 1962

-

Christ in Glory in Jaleyrac

-

The exterior of a chapel attached to the St. Nicholas Church, Tallinn

Notes

[edit]- ^ The lexically similar Maestà, Italian for "majesty", conventionally designates an iconic formula of the enthroned Madonna with the child Jesus.

- ^ "Traditio Legis, Traditio Clavum - Iconography". Archived from the original on 2013-06-23. Retrieved 2013-12-23.

- ^ Eduard Syndicus; Early Christian Art; p. 96; Burns & Oates, London, 1962. Hall, pp. 78–80

- ^ James Hall, A History of Ideas and Images in Italian Art, pp. 92–93, 1983, John Murray, London, ISBN 0-7195-3971-4

- ^ Christ in early examples is Christ the Teacher: the gesture of Christ's right hand is not the gesture of blessing, but the orator's gesture; the identical gesture is to be seen in a panel from an ivory diptych of an enthroned vice-prefect (vicarius), a Rufius Probianus, ca 400, of which Peter Brown remarks, "With his hand he makes the 'orator's gesture' which indicates that he is speaking, or that he has the right to speak." Staatsbibliothek Berlin. Illustrated in Peter Brown, "Church and leadership" in Paul Veyne, editor, A History of Private Life: From Pagan Rome to Byzantium 1987, p 272.

- ^ Syndicus:143

- ^ Schiller, Vol 2, pp. 188–189, 202

- ^ Emile Mâle, The Gothic Image: Religious Art in France of the Thirteenth Century, p. 365–376, English trans of 3rd edn, 1913, Collins, London (and many other editions)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- Schiller, Gertrud, Iconography of Christian Art, Vol. II, 1972 (English trans from German), Lund Humphries, London, ISBN 0853313245

External links

[edit] Media related to Majestas Domini at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Majestas Domini at Wikimedia Commons Media related to Reliefs of Majestas Domini at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Reliefs of Majestas Domini at Wikimedia Commons- Christ in Majesty

- (Getty Museum,); Christ in Majesty, manuscript illumination, German, (Hildesheim), about 1170s

- Christ in Majesty, with apocalypse details: chancel painting, St Mary's Church, Kempley, Gloucestershire c.1120

- Christ in Majesty: illumination in the Aberdeen Bestiary, late twelfth century

- Definition of Deesis—Includes photos of the Deesis in the Hagia Sophia.