Main Customs Office (Munich)

The former Main Customs Office of Munich (German: Hauptzollamt München) is a historic building complex located at Landsberger Straße 122-132 in the Schwanthalerhöhe district of Munich. Its construction dates back to 1912, and it served as the Munich Main Customs Office I until 2004 and later housed various departments of the Federal Customs Administration. The architecture of the buildings combines elements of late Art Nouveau and reform architecture.[1] It is renowned as an exemplary representation of the "monumental architecture of the Prince Regent period" showcasing the grandeur and independence of the Bavarian kingdom.[2] The massive former warehouse is particularly striking, stretching 180 meters long and crowned by a glass dome. Towering at a height of 45 meters, the dome resembles a crystalline structure that emerges from the center of the building.[3]

Due to its location next to the Donnersbergerbrücke between Landsberger Straße and the railroad tracks, the building is very present in the cityscape and can be seen from the Mittlerer Ring on the Donnersbergerbrücke as well as from all trains entering or leaving Munich Central Station.

History

[edit]

Since 1807, Bavaria had a well-organized financial administration that included a General-Zoll- und Maut-Direktion (General Customs and Toll Directorate).[4] In 1819, the royal authorities were reorganized under the 1818 constitution of the Kingdom of Bavaria under Maximilian von Montgelas, and a tripartite structure was established consisting of the Direktion (Directorate), Hauptzollämtern (Main Customs Offices), and subordinate Zollämtern I. und II (Customs Offices I and II).[5] As the system evolved, in 1874, the main customs office in Munich moved to a building designed by Friedrich Bürklein on Bayerstraße near Munich's main train station. Subsequently, in 1880, the customs and toll directorate was integrated into the new Royal General Directorate for Customs and Indirect Taxes, bringing tax offices under the purview of the main customs offices. Later 1901, a second main customs office was established in Haidhausen, at the Munich East station to cover the eastern part of Munich up to the district court of Schwaben.[6]

As long-distance trade flourished and a new customs law was introduced in 1906, the existing Main Customs Office I could no longer meet the increasing demands. The volume of goods passing through customs experienced significant growth. In the beginning, there were 24,000 colli of dry goods and 3,560 colli of liquid goods. However, by 1911, sales had soared to 48,000 packages of dry goods and 7,000 packages of liquid goods.[7] An expansion on the existing site was not feasible, prompting the government to commission a new building for the Munich I Main Customs Office in 1908. The site chosen was the former forestry timber yard of the Royal Bavarian Forestry Administration, located further west on Landsberger Strasse, an extension of Bayerstraße out of town. This required the purchase and demolition of nine private houses along Landsberger Strasse. Due to the relocation of the Technical Examination and Training Institute of the Customs Administration, previously situated alongside the Royal General Directorate for Customs and Indirect Taxes in the Altes Hof, it became essential to integrate the institute into the new building. As the new location was situated on the outskirts of the city, service apartments were also provided to accommodate the staff.[8]

Design and construction

[edit]

The building was designed by Hugo Kaiser, a royal government and building assessor. Together with three other officials from the building administration, he conducted a study trip to modern customs buildings, the free port of Hamburg, and various industrial buildings that could serve as potential models.[9] Based on their findings, the plans were developed with a focus on creating a spacious layout. The estimated space requirement was increased by one-third as a reserve for the future and was incorporated into the building’s specifications. The design and model were approved by Prince Regent Luitpold in 1908. Construction of the complex took place from 1909 to 1912, under the supervision of Kaiser, while the royal ministerial councilor Gustav Freiherr von Schacky auf Königsfeld from the Ministry of Finance oversaw the construction process.[10] On July 1, 1912, the new main customs office was inaugurated by Prince Ludwig on behalf of his father, who was already 91 years old at the time.[11] The previous location of the customs office was taken over by the Royal Bavarian State Railways.

The warehouse and administration buildings were built using a reinforced concrete skeleton, making them one of the pioneering examples of such large-scale reinforced concrete structures in Europe.[12] Prominent construction companies from across southern Germany were commissioned for the construction work.[13] The Munich-based firm Gebr. Rank and Heilmann & Littmann were responsible for the execution of the reinforced concrete structures, while the wrought iron work was carried out by F. F. Kustermann. The heating system was supplied by Eisenwerke Kaiserslautern, cranes were sourced from the Nuremberg machine factory Wilhelm Spaeth and the Würzburg company Georg Noell & Co, and the pneumatic tube system was created by Alois Zettler. Siemens-Schuckertwerke provided various other technical installations for the building. The total cost of the Main Customs Office amounted to 1,760,000 marks for the land and 8,170,500 marks for the buildings. This figure also includes the construction expenses of 485,000 marks for the customs facilities at Munich South Station, which were built to facilitate customs clearance for fruit and vegetables at the Munich wholesale market hall. Additionally, the cost encompasses the land and buildings for the new Forsthof in Haidhaus.[14]

Usage

[edit]During the early years of the Main Customs Office, the storage space was not fully utilized, resulting in parts of the building being rented out to local companies in Munich. However, during World War I, a significant portion of the warehouse, counter halls, and revision halls were converted into an auxiliary hospital.[15] In 1919, the Hauptzollamt München III (Munich Main Customs Office III) was established in the Bürkleinbau on Bayerstraße. As a result, Hauptzollamt München I (Munich Main Customs Office I) was only responsible for customs clearance in Munich, excluding the Ostbahnhof station, while the other two Hauptzollämter took charge of subordinate customs offices, customs inspectorates, tax offices, and tax posts.[16] The main customs office in Munich also served as an auxiliary customs office.

During World War II, the Wehrmacht (armed forces) utilized a quarter of the warehouse space as a depot. The building suffered partial damage from demolition bombs during air raids and was also looted by the Munich population the night before the U.S. Army arrived.[17] After the war, the Americans used approximately two-thirds of the warehouse as a PX depot, making alterations that resulted in the loss of many artistic and structural details. Customs operations continued in the remaining parts of the building. In 1963, ownership of the building was transferred from the Free State of Bavaria to the Federal Finance Administration. In 1969, the U.S. Army vacated the premises, and the entire facility once again came under German administration.

Since 1976, the Main Customs Office has been a listed building.[1] Starting in 1977, the Munich Finance Building Office I initiated a sectional renovation and reconstruction project, costing approximately 28 million German marks, with most of the work completed by the building's 75th anniversary in 1987.[8] Between 1994 and 2002, the three former main customs offices in Munich (West, Central, and Airport) were merged.[18] By 2007, the office management and most departments had gradually relocated to the Sophienstraße headquarters at the Old Botanical Garden. Customs clearance at Landsberger Strasse ceased, with only mail items being processed towards the end. The vacated rooms were subsequently utilized by the Customs Investigation Department, the Traffic Routes Control Unit, and, in 2004, the Financial Control for Clandestine Employment, resulting in restricted public access to the building for security reasons.

The Main Customs Office has also served as a filming location for television productions and hosted various events. In 1999, Christian Dior presented its fall/winter collection in the counter hall, and the auditing room was transformed into a dance studio for the ZDF Christmas series Anna. The building was featured significantly in two episodes of Die Verbrechen des Professor Capellari, one episode of Siska, and the miniseries Der Wunschbaum.[19] Until 1998, the main customs office housed the collection of so-called German art from the National Socialist era and looted art. The Munich Chief Finance Office was responsible for managing these artworks under the administration of the federal government.[20] The art collection comprised works acquired from state collections during the Third Reich or unlawfully gathered from various locations across Europe, which were subsequently cataloged by the Americans at the Central Collecting Point after the war.[21] Presently, the fifth floor of the warehouse is rented to the Deutsches Museum, which has relocated parts of its depot to the premises.[18] Since 2015, the State Office for the Preservation of Historical Monuments has also utilized a section of the Main Customs Office as a depot for archaeological finds.[22]

The Technical Examination and Training Institute underwent extensive renovation from 2011 to 2014 after its laboratories were relocated to a new building near Munich Airport.[23] Subsequently, the offices were occupied by customs service offices and the Federal Real Estate Agency. The attached residential buildings are rented out by the Bundesanstalt für Immobilienaufgaben, primarily to federal officials.

Structures

[edit]

The main customs office stands as one of the prominent architectural achievements of the Prince Regent period, spanning from 1886 to 1912.[24] These grand state buildings were constructed to symbolize "Bavaria's independence" and "insistence on reserve rights" compared to the other states in the German Empire, which had been united since 1871.[25] To this day, these structures continue to shape the city's landscape, reflecting a commitment to exceptional quality and making Munich not only a cultural hub renowned for its art, music, theater, literature, and science but also reached the "peak of Munich's national and European importance" in architecture at the turn of the 19th to the 20th century. The building of "Kulturstadt München" (Munich City of Culture) stands among the city's most significant architectural landmarks.[26]

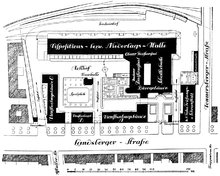

The site, spanning approximately 35,000 square meters, which is roughly rectangular in shape and encompasses a total floor space of 14,000 square meters, accounts for approximately 40% of the land's area.[27] The building complex comprises the administrative building at the core of the site, the 180 m long warehouse building adjoining at right angles to the north and running west, the Customs Technical Examination and Training Institute set off to the east and three residential blocks for employees to the south on Landsberger Straße. The layout is designed as a multi-wing complex, featuring buildings of varying heights arranged in a stepped manner, along with several courtyards and green spaces. The street-facing facade is defined by archways and walls, giving the complex a distinct character akin to a self-contained fortress for work and living purposes.[28] The construction of the complex in uniform planning allowed the optimal adaptation of the buildings to the customs procedures and the separation of the flow of goods by arranging the buildings around several courtyards.[29] This entire structure was built on the former site of the customs office.

The Münchner Neuesten Nachrichten concluded the day after the opening:[30]

The entire building complex, "pleasing on the outside, functional on the inside and equipped with all the achievements of modern times, is a new adornment for Munich and shows how taste and usability, how comfort and technical perfection can go hand in hand even in state buildings. And even if no merchant likes to pay the duty, I almost believe that he will at least grow fond of the new building on Landsberger Strasse and enjoy visiting it."

Architecture

[edit]

The administrative building, serving as the actual Customs Office, is oriented in a north-south direction, featuring a prominent façade with a convex gable and clock tower. Set back from Landsberger Straße, its entrance area is accessed through a courtyard of honor, framed by the testing facility to the east and the side wing of one of the residential buildings. The front of the building consists of a transverse office wing, leading to the central counter hall. This hall spans three floors, measuring 35 meters in length, 14.5 meters in width, and has a height of 14 meters.[31] Notable features include a barrel vault with robust reinforced concrete frame trusses and ceiling surfaces adorned with coffered stucco. Adjacent to the counter hall is the lower auditing room, with an atrium between them extending to the basement, providing vehicle access to the cellars via a ramp.

Behind the administrative building, perpendicular to it and facing the railroad tracks is the warehouse wing. This wing consists of four main floors and, including the roof and cellars, a total of nine floors, offering a combined storage area of approximately 30,000 square meters.[32] The first floor was dedicated to customs clearance, while the upper floors served as bonded warehouses.[33] Special storage rooms were allocated for specific types of goods: flammable goods had a separate small hall in the courtyard, motor vehicles were stored in an enclosed shelter, and malodorous goods had designated storage areas at the end of the hall, accompanied by a covered yet predominantly open porch. Fats, oils, and sparkling wine were stored in the basement. Additionally, there were rooms for meat inspection by a veterinarian.[10] In the eastern third of the warehouse, the dome of the light well interrupts the massive gable roof. Extending 45 meters high and overhanging the warehouse's ridge by 18 meters, the dome takes the form of an elongated decagon with a dome-shaped design converging at two ridge points. Its vaults, featuring three circumambulations, are considered the prototype of reinforced concrete trusses.[34] The dome is covered with copper, which has acquired a patina that was meticulously restored during renovations. The light well, originally open to the storage areas, was mostly closed off after the renovations, as the warehouse floors were converted into office spaces.

Situated to the east of the Ehrenhof, the Technical Examination and Training Institute of the Customs Administration comprised office and business rooms, several laboratories, and a central lecture hall equipped with modern slide projectors and an extensive collection of sample goods. The laboratories included a general examination laboratory for official purposes and studies, a specialized laboratory for beer and wine analysis, a training laboratory for practical instruction on chemical examinations, a precision balance room, a microscopy room, and a basement room for burning tests. The building also housed three service apartments.[35]

The four-story residential wings along Landsberger Straße consisted of 47 apartments designated for customs office employees. The apartments varied in size and rank, ranging from seven-room units for the head of the office, four- to five-room apartments for customs inspectors, to three-room apartments for other officials, supervisors, and machinists. All apartments were equipped with gas stoves and central heating, ensuring a high standard of living for ordinary employees. The more upscale units featured private bathrooms and electricity. The courtyard between the residential buildings was landscaped and included a children's playground.[21]

The complex's architectural appeal is further enhanced by the varying building heights and the diverse roofscape, featuring dormers and dwarf houses. The testing facility and residential buildings have hipped roofs, while the administrative wing and warehouse exhibit gable roofs. The ground plans and building forms exemplify the principles of reform architecture, and the facades of all buildings are adorned with sculptural ornaments made of shell limestone and bush-hammered concrete, reflecting the late Art Nouveau style. While the side facing the railroad appears more restrained, the other sides of the complex are inviting and visually captivating, with the administrative and educational areas designed to be representative.[3]

Building Technology

[edit]

The equipment of the office used all the techniques of the time: inside there were air humidification systems, as well as air-deducting filters and a fresh air supply device. The controlled climate in the storage rooms was of particular importance, especially since all tobacco imports from Greece to the German Reich were processed through Munich.[9] The warehouse was equipped with a direct rail siding, complete with a rope hoist for moving wagons, allowing goods arriving by rail to be unloaded directly inside the customs office. Overhead cranes with load capacities ranging from 4 to 25 tons, along with four freight elevators capable of carrying up to 1.5 tons each, facilitated the transportation of goods within the facility.[10]

To prevent dust, the exhaust air from the examination rooms underwent filtration, and the adjoining offices were maintained under slight positive pressure. Special shafts were installed to allow packaging and waste to be disposed of directly into airtight waste containers from the inspection rooms.[36] Washrooms for employees were in the basement, and in the customs yard, a large basin served as a horse trough. The customs office had its own transformer to convert electricity from the main station's power plant to the required voltage levels. The two clearance yards were equipped with arc lamps for illumination. All buildings were equipped with central heating or connected to a district heating system. The office had an in-house telephone system, a centrally controlled electric clock system located in the office of the head of the authorities, and a pneumatic tube system for efficient communication.

Artistic decor

[edit]

The sculpture work on the facades and inside the administration building was carried out by Georg Albertshofer and Julius Seidler, with Wilhelm Riedisser creating a portal sculpture. The vestibule and counter hall were adorned with wrought decorative grilles, intricately carved stair railing supports, and counter fronts made of polished shell limestone. Wall decorations in stencil painting, including palmette friezes, beadwork, and coffers dividing the walls, adorned other areas. Many original furnishings have been preserved, including doors, railings, a sculpture, and several capitals in the staircase of the administrative wing. Notably, the director's office retains its original wood paneling and furnishings, providing a glimpse into the historical atmosphere of the period.[8]

During the restoration between 1977 and 1987, the counter hall required professional repairs to fix ceiling cracks caused by war damage. The plaster covering the coffers in the belt arches was removed, allowing for the reconstruction of stucco profiles and stencil painting based on paint residues and photos. Under layers of plaster, the original front wall made of shell limestone slabs and columns was uncovered and exposed. Some ornamental grilles were not preserved and had to be recreated based on photographs. The wooden fixtures in the plinth zones were lost and could not be reconstructed due to budget constraints. Instead, a painted plinth with a crested pattern and a stenciled frieze, like the neighboring corridors, was used as a replacement.[37]

In the office associated with the upper revision room, the stencil painting was rebuilt by church painter Peter Hippelein,[38] following the discovery of paint remains under later layers of paint and reference to historical photographs from the construction period. After consultation with the State Office for the Preservation of Historical Monuments, the impression of the glazing of the light well, which had been closed in the meantime, was suggested by painted-on glass blocks. The coffered paneling, in vibrant and fresh hues, was reinstated to restore the original character of an "upscale bureau." Recapturing the ambiance of the era.[39]

The vestibule still retains stucco and a ceiling fresco. The fresco depicts the Patrona Bavariae surrounded by putti, symbolizing trade, and the foundation of customs. However, the wall facings and columns made of shell limestone were mostly lost, with only a small portion remaining. During the renovation, a coating similar to lime slabs was used as a replacement, allowing visitors to still experience the grandeur of this historic space while preserving its cultural significance.[40]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege

- ^ Läpke 1995, pp. 111

- ^ a b Bernd Raschert: Instandsetzung des Hauptzollamts München-West. In: Die Mappe – Deutsche Malerzeitschrift, Ausgabe 7/87, pp. 9

- ^ Walter Wilhelm: Maut – Zoll 1834–1984, Oberfinanzdirektion München 1984, pp. 9

- ^ Walter Wilhelm: Maut – Zoll 1834–1984, Oberfinanzdirektion München 1984, pp. 22

- ^ Münchener Jahrbuch 1901, Carl Gerber, München 1901, pp, 400 and 448

- ^ Zollanlagen, Industriebau 1914, pp. 154

- ^ a b c Denkmäler in Bayern, München-Südwest, Halbband 2 pp. 375–377

- ^ a b Läpke 1995, pp. 112

- ^ a b c Zollneubauten, Zentralblatt 1912, Ausgabe 84, pp. 542–544

- ^ Franke-Fuchs 2012, pp. 13

- ^ Bernd Raschert: Instandsetzung des Hauptzollamts München-West. In: Die Mappe, Deutsche Malerzeitschrift, Ausgabe 7/1987, pp. 9–12.

- ^ Zollanlagen. In: Der Industriebau, Jahrgang 1914, pp. 172.

- ^ Zollanlagen. In: Der Industriebau, Jahrgang 1914, pp. 171.

- ^ Das Reservelazarett D im Hauptzollamtsgebäude an der Landsbergerstrasse. In: Feldärztliche Beilage zur Münchner Medizinischen Wochenschrift, 15. Dezember 1914, pp. 2395 f.

- ^ Münchener Jahrbuch 1919, Carl Gerber, München 1919, pp. 359, 422

- ^ Eduard Zitzelsberger (1995). Die Nacht im Zollamt. In: Marita Kraus (Hrsg.): Verdunkeltes München. Buchendorfer Verlag, 1995. pp. 196–200. ISBN 3-927984-41-8.

- ^ a b Süddeutsche Zeitung: Ein Prachtbau für Zöllner, 27. Juni 2012, pp. R5

- ^ Franke-Fuchs 2012, pp. 39

- ^ "BADV - Central Collecting Point - Central Collecting Point". 2016-01-22. Archived from the original on 2016-01-22. Retrieved 2023-07-21.

- ^ a b Martin Reindl (2005). Das Hauptzollamt – fortschrittliche Technik hinter historischen Fassaden. In: Friederike Meier, Serge Perouansky, Jürgen Stintzig (Hrsg.): Das Westend – Geschichte und Geschichten eines Münchner Stadtteils. StattPlan Verlag, München, 2005. pp. 46–49. ISBN 3-9801647-6-4.

- ^ Stephanie Gasteiger. "Großer Umzug – Archäologische Funde ziehen ins Hauptzollamt München. In: Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege" (PDF).

- ^ Franke-Fuchs 2012, pp. 36 f.

- ^ Diese Einordnung stützt sich auf: Heinrich Habel: München – ein entwicklungs- und kulturgeschichtlicher Überblick. In: Heinrich Habel, Johannes Hallinger, Timm Weski: Landeshauptstadt München – Mitte (= Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege [Hrsg.]: Denkmäler in Bayern. Band I.2/1). Karl M. Lipp Verlag, München 2009. pp. LIX–CXVI, LXXIV ff. ISBN 978-3-87490-586-2.

- ^ Habel, pp. LXXVI

- ^ Habel, pp. LXXVII

- ^ Zollanlagen, Industriebau 1914, pp. 163

- ^ Denkmäler in Bayern, München-Südwest, Halbband 2, pp. 376

- ^ Zollneubauten, Zentralblatt 1912, Ausgabe 83, pp. 536

- ^ Zollneubauten, Zentralblatt 1912, Ausgabe 83, pp. 536

- ^ Zollanlagen, Industriebau 1914, pp. 165

- ^ Bayerischer Architekten- und Ingenieursverein (1978). München und seine Bauten, F. Bruckmann, 1912. Nachdruck von 1978. pp. 517–519. ISBN 3-7654-1747-5.

- ^ Zollneubauten, Zentralblatt 1912, Ausgabe 83, pp. 538

- ^ Bernd Raschert: Instandsetzung des Hauptzollamts München-West. In: Die Mappe – Deutsche Malerzeitschrift, Ausgabe 9/87, pp.17

- ^ o. V.: Die Zollneubauten an der Landsbergerstrasse in München. In: Süddeutsche Bauzeitung Jahrgang 22, Nr. 45, pp.357–361, 360

- ^ Zollanlagen, Industriebau 1914, pp. 169

- ^ Bernd Raschert: Instandsetzung des Hauptzollamts München-West. In: Die Mappe – Deutsche Malerzeitschrift, Ausgabe 8/87, pp. 15–18

- ^ Läpke 1995, pp. 121

- ^ Bernd Raschert: Instandsetzung des Hauptzollamts München-West. In: Die Mappe – Deutsche Malerzeitschrift, Ausgabe 7/87, pp. 11

- ^ Bernd Raschert: Instandsetzung des Hauptzollamts München-West. In: Die Mappe – Deutsche Malerzeitschrift, Ausgabe 9/87, pp. 15–18

Further reading

[edit]- o. V.: Die Zollanlagen an der Landsberger Straße in München. In: Der Industriebau, 5. Jahrgang, Ausgabe 7 (15. Juli 1914), pp. 151–172.

- Wolfgang Läpke (1995), Das Hauptzollamt an der Landsberger Straße. In: Monika Müller-Rieger (Hrsg.): Westend – Von der Sendlinger Haid' zum Münchner Stadtteil, Buchendorfer Verlag, 1995, pp. 111–123, ISBN 3-927984-29-9.

- Bernd Raschert: Instandsetzung des Hauptzollamts München-West. Artikelserie in Die Mappe – Deutsche Malerzeitschrift, Callway Verlag, Ausgaben 7–9, 1987.

- Siglinde Franke-Fuchs: 100 Jahre Zoll-Dienstgebäude Landsberger Straße 124, München. Hauptzollamt München, 2012.

- Denis A. Chevalley; Timm Wesk, Landeshauptstadt München – Südwest (= Bayerisches Landesamt für Denkmalpflege [Hrsg.]: Denkmäler in Bayern. Band I.2/2)., Karl M. Lipp Verlag, München 2004, pp. 375–377, ISBN 3-87490-584-5.

External links

[edit]- Commons: Main Customs Office Munich – a collection of images, videos and audio files

- Bernd Raschert: On the building history of the main customs office in Munich-West.