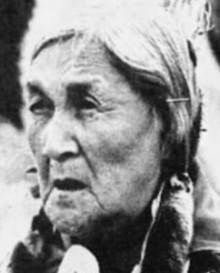

Maggie Black Kettle

Maggie Black Kettle (August 20, 1917 – September 14, 2011) was a Canadian community leader in the Siksika Nation. She taught traditional crafts, dance, and the Blackfoot language in Calgary. She was a storyteller, and appeared in film and television programs in her later years.

Early life

[edit]Black Kettle was born in the Siksika First Nations Reserve near Gleichen, Alberta.[1] At age 7, she was enrolled at a Catholic boarding school in Cluny,[2] where she was forbidden to speak Blackfoot, her only language as a child.[3][4][5]

Career

[edit]Black Kettle was considered a matriarch and spiritual leader of the Siksika people.[1][6][7] She attended community events, including local ceremonies,[8] large North American powwows, and the Indian Village exhibition at the annual Calgary Stampede. She taught the Blackfoot language and traditional crafts and dances at the Plains Indian Cultural Survival School,[9] and at the Piitoayis Family School, both in Calgary.[10][11][12] During the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, Black Kettle shared her weather forecasts for the event.[13] The following year, she cofounded the city's Native Awareness Week.[14] She served on the board of the Calgary Indian Friendship Centre,[6] and assisted First Nations women who were new to the city. She was recognized with a Woman of Distinction Award from the YWCA of Calgary in 1994.[3][15] She was a member of the Sundance Society Motookiiks, the Buffalo Women's Society, and the Horn Society.[16]

Black Kettle was a storyteller in her later years,[17] and appeared in Canadian film and television shows, including roles in North of 60 (1993), Medicine River (1993),[18][19] Wild America (1997), and Dream Storm (2001).[11]

Personal life

[edit]When she was 16 years old, she married Nickolas Black Kettle, in an arranged union. They ran a farm together, and had seven children.[20] She also raised some of her many grandchildren. She was widowed when her husband died in 1973, and she died in 2011, aged 94 years, at a hospital in Calgary.[1][3][20]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Maggie Black Kettle: Spiritual Elder Passed on Cree and Blackfoot to Future Generations". National Post. 2011-09-27. p. 24. Retrieved 2021-08-18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Mayes, Alison (1994-06-19). "Making a Difference: Maggie Black Kettle Arts and Culture". Calgary Herald. p. 15. Retrieved 2021-08-18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Meili, Dianne (2011). "Blackfoot Elder overcame fear to pass on traditional ways". AMMSA. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ Dempsey, Lloyd James (1999). Warriors of the King: Prairie Indians in World War I. Canadian Plains Research Center, University of Regina. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-88977-101-7.

- ^ "Maggie Black Kettle, Alberta". Calgary Herald. 1997-07-01. p. 50. Retrieved 2021-08-18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b "Storyteller Tries to Keep Culture Alive". Edmonton Journal. 1992-12-27. p. 7. Retrieved 2021-08-18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dudley, Wendy (1992-12-24). "Native Nativity". Calgary Herald. p. 23. Retrieved 2021-08-18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Principal renamed 'Rain Woman' by Blackfoot". CBC News. June 25, 2009. Retrieved August 17, 2021.

- ^ "Vanishing society: 'I Think We're Going to Lose our Heritage'". Calgary Herald. 1988-09-11. p. 62. Retrieved 2021-08-18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dils, Ann; Albright, Ann Cooper (2013-06-01). Moving History/Dancing Cultures: A Dance History Reader. Wesleyan University Press. pp. 123–124. ISBN 978-0-8195-7425-1.

- ^ a b Voyageur, Cora J. (2018-11-14). My Heroes Have Always Been Indians: A Century of Great Indigenous Albertans. Brush Education. pp. 40–41. ISBN 978-1-55059-754-7.

- ^ Zickefoose, Sherri (2002-12-24). "School Plants Deep Cultural Roots". Calgary Herald. p. 91. Retrieved 2021-08-18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Braungart, Susan (1988-02-06). "Wise Weather-Watchers Wonder What's in the Wind". Calgary Herald. p. 10. Retrieved 2021-08-18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lowey, Mark (1989-04-11). "Native Event to Push Goodwill". Calgary Herald. p. 14. Retrieved 2021-08-18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Maggie Black Kettle". Calgary Herald. 1994-06-04. p. 26. Retrieved 2021-08-18 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Remembering the life of Maggie Black Kettle 1917 - 2011". Calgary Sun. September 18, 2011. Retrieved 2021-08-17.

- ^ "Native Day Care; 'Into Young Hands Shall the Feather be Passed'/Wendy Dudley - Newspapers.com". Newspapers.com. Retrieved 2021-08-18.

- ^ Hilger, Michael (2015-10-16). Native Americans in the Movies: Portrayals from Silent Films to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 404. ISBN 978-1-4422-4002-5.

- ^ Schweninger, Lee (2013-05-01). Imagic Moments: Indigenous North American Film. University of Georgia Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-8203-4514-7.

- ^ a b Zickefoose, Sherri (2011-09-24). "Black Kettle was a Spiritual Leader". Times Colonist. p. 2. Retrieved 2021-08-18 – via Newspapers.com.

External links

[edit]- Maggie Black Kettle at IMDb

- Maggie Black Kettle with grandsons, Calgary (1968), photograph in the collection of Glenbow Museum

- Dianne Meili, Those who Know: Profiles of Alberta's Native Elders (NeWest Press 1991); includes a profile of Maggie Black Kettle