Magdalenenberg

Magdalenenberg is the name of an Iron Age tumulus near the city of Villingen-Schwenningen in Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is considered the largest tumulus from the Hallstatt period in Central Europe with a volume of 33.000 cubic meters.

History

[edit]

The central tomb, where an early Celtic Prince (Keltenfürst) was buried, has been dendrochronologically dated to 616 BC. The mound, which is still distinctly silhouetted against the landscape, once possessed a height of 10–12 m (now about 8 m) and a diameter of 104 meters. Little is known about the people who erected it, and current research focusses on the identification of their settlement.[1] In the decades after the Prince's death, 126 further graves were mounted concentrically around the central tomb. At around 500 BCE, this tomb was plundered by grave robbers, whose wooden spades were later found by archaeologists.

During the Middle Ages and the Early Modern period, the Magdalenenberg was still seen as a significant landmark, although knowledge about its former purpose had been lost. In the 1640s, when Villingen was shaken by a series of Witch trials, several women confessed under torture to have danced with the devil on the top of the hill.

Archaeologists began to be interested in the site in as early as the 1880s. In 1890, a team led by forest official Hubert Ganter dug a cone from the top of the hill into the central tomb, expecting to find hidden treasures. However, because of the ancient robbery of the tomb, only few finds turned up. Among those were parts of a wooden carriage, the Prince's bones, and the skeleton of a young pig.

From 1970 to 1973, the archaeologist Konrad Spindler led another scientific exploration, now not only focussing on the central tomb, but on the surrounding graves as well. By excavating the whole hill, all 127 graves could be explored and finds like bronze daggers, spearheads, an iberian belt hook and a precious amber necklace were unearthed. Some of those objects are proof for trade connections to the Mediterranean area and the eastern alpine region, others allow rare insights into the Celtic burial rites. They are now on display in the Franziskanermuseum (Franciscan Museum) in Villingen, along with the Prince's wooden burial chamber (one of the largest wooden objects from the era in any museum).

Since September 2014, a hiking trail called "Keltenpfad" (Celtic Path) connects the Magdalenenberg with the Franziskanermuseum. Along the road, panels inform about the site's history and significance. In this context, some of the wooden poles were reconstructed at their historical position.

Possible calendar function

[edit]Since 2011, the Magdalenenberg attracted new international attention as the possible site of an early moon calendar.[2] The archaeologist Allard Mees of the Romano-Germanic Central Museum (Mainz) suggested that the alignment of the graves represents the stellar constellation at the time of their erection. Another part of his theory is based on large wooden poles that were found inside the hill and whose function remains a mystery. He interprets them as markers directing to the position of the lunar standstill, thus allowing the Celts to prognose lunar eclipses.[3][4] His theory is hotly debated among scholars and has been criticized by some for lacking sufficient evidence,[5] while others[who?] have welcomed the new approach.

Gallery

[edit]-

Crescent-shaped razor from the Magdalenenberg

-

Amber-head pins

-

Brooches

-

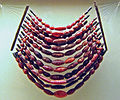

Bracelets from the Magdalenenberg

-

Amber necklace from the Magdalenenberg

-

Excavation photo of the burial chamber

-

Aerial view of the Magdalenenberg

See also

[edit]- Alte Burg (Langenenslingen)

- Glauberg

- Hochdorf Chieftain's Grave

- Heuneburg

- Hohenasperg

- Ipf (mountain)

- Vix Grave

References

[edit]- ^ Knopf, Thomas (2010). "Neue Forschungen im Umland des Magdalenenbergs". In Tappert, C.; Later, Ch.; Fries-Knoblach, J.; Ramsl, P.C.; Trebsche, P.; Wefers, S.; Wiethold, J. (eds.). Wege und Transport. Frühgesch. Arch. Mitteleuropas, Langenweissbach. Vol. 69. Nürnberg, DE: Sitzung AG Eisenzeit. pp. 209–220.

- ^ "Magdalenenberg: Germany's ancient moon calendar" Current World Archaeology, Nov 2011". 6 November 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- ^ Mees, Allard (2017). "Der Magdalenenberg und die Orientierung von keltischen Grabhügeln. Eine bevorzugte Ausrichtung zum Mond?". In Dirk Krausse; Marina Monz (eds.). Neue Forschungenzum Magdalenenberg, Archäologische Informationenaus Baden-Württemberg (in German). Stuttgart, DE. pp. 76–93. ISBN 978-3-942227-31-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Mees, Allard (2011). "Der Sternenhimmel vom Magdalenenberg. Das Fürstengrab bei Villingen-Schwenningen – ein Kalenderwerk der Hallstattzeit". Jahrbuch des Römisch-Germanischen Zentralmuseums Mainz (in German). 54 (1). Mainz, DE: 217–264. doi:10.11588/jrgzm.2007.1.17008.

- ^ Rohde, Claudia (2012). Kalender in der Urgeschichte. Fakten und Fiktion (in German). Rahden.