American Mafia

| Founded | 1868[1] |

|---|---|

| Founding location | New York City, New Jersey, Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit, New Orleans, Boston, and various other Northeastern and Midwestern cities in the United States |

| Years active | Since the mid-19th century |

| Territory |

|

| Ethnicity | |

| Membership (est.) | Over 3,000 members and associates[3] |

| Activities | Racketeering, illegal gambling, loan sharking, extortion, drug trafficking, labor union corruption, business infiltration, political corruption, money laundering, fraud, theft, counterfeiting, smuggling, weapons trafficking, kidnapping, assault, murder, bombing, arson, prostitution and pornography[4] |

| Allies |

|

| Rivals |

|

The American Mafia,[23][24][25] commonly referred to in North America as the Italian-American Mafia, the Mafia, or the Mob,[23][24][25] is a highly organized Italian-American criminal society and organized crime group. In North America, the organization is often colloquially referred to as the Italian Mafia or Italian Mob, though these terms may also apply to the separate yet related Sicilian Mafia or other organized crime groups in Italy, or ethnic Italian crime groups in other countries. The organization is often referred to by its members as Cosa Nostra (Italian pronunciation: [ˈkɔːza ˈnɔstra, ˈkɔːsa -], "Our Thing" or "This Thing of Ours") and by the American government as La Cosa Nostra (LCN). The organization's name is derived from the original Mafia or Cosa Nostra, the Sicilian Mafia, with "American Mafia" originally referring simply to Mafia groups from Sicily operating in the United States.

The Mafia in the United States emerged in impoverished Italian immigrant neighborhoods in New York's East Harlem (or "Italian Harlem"), the Lower East Side, and Brooklyn; also emerging in other areas of the Northeastern United States and several other major metropolitan areas (such as Chicago and New Orleans)[26] during the late 19th century and early 20th century, following waves of Italian immigration especially from Sicily and other regions of Southern Italy. Campanian, Calabrian and other Italian criminal groups in the United States, as well as independent Italian-American criminals, eventually merged with Sicilian Mafiosi to create the modern pan-Italian Mafia in North America. Today, the Italian-American Mafia cooperates in various criminal activities with Italian organized crime groups, such as the Sicilian Mafia, the Camorra of Campania and the 'Ndrangheta of Calabria. The most important unit of the American Mafia is that of a "family", as the various criminal organizations that make up the Mafia are known. Despite the name of "family" to describe the various units, they are not familial groupings.[27]

The Mafia is most active in the Northeastern United States, with the heaviest activity in New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, New Jersey, Pittsburgh, Buffalo, and New England, in areas such as Boston, Providence, and Hartford. It also remains heavily active in Chicago and has a significant and powerful presence in other Midwestern metropolitan areas such as Kansas City, Detroit, Milwaukee, Cleveland, and St. Louis. Outside of these areas, the Mafia is also very active in Florida, Phoenix, Las Vegas, and Los Angeles. Mafia families have previously existed to a greater extent and continue to exist to a lesser extent in Northeastern Pennsylvania, Dallas, Denver, New Orleans, Rochester, San Francisco, San Jose, Seattle, and Tampa. While some of the regional crime families in these areas may no longer exist to the same extent as before, descendants have continued to engage in criminal operations, while consolidation has occurred in other areas, with rackets being controlled by more powerful crime families from nearby cities.[28]

At the Mafia's peak, there were at least 26 cities around the United States with Cosa Nostra families, with many more offshoots and associates in other cities. There are five main New York City Mafia families, known as the Five Families: the Gambino, Lucchese, Genovese, Bonanno, and Colombo families. The Italian-American Mafia has long dominated organized crime in the United States. Each crime family has its own territory and operates independently, while nationwide coordination is overseen by the Commission, which consists of the bosses of each of the strongest families. Though the majority of the Mafia's activities are contained to the Northeastern United States and Chicago, they continue to dominate organized crime in the United States, despite the increasing numbers of other crime groups.[29][30]

Terminology

[edit]The word mafia (Italian: [ˈmaːfja]) derives from the Sicilian adjective mafiusu, which, roughly translated, means "swagger" but can also be translated as "boldness" or "bravado". In reference to a man, mafiusu (mafioso in Italian) in 19th-century Sicily signified "fearless", "enterprising", and "proud" according to scholar Diego Gambetta.[31] In reference to a woman, the feminine-form adjective mafiusa means "beautiful" or "attractive". In North America, the Italian-American Mafia may be colloquially referred to as simply "The Mafia" or "The Mob"; however, without context, these two terms may cause confusion as "The Mafia" may also refer to the Sicilian Mafia specifically or Italian organized crime in general, while "The Mob" can refer to other similar organized crime groups (such as the Irish Mob) or organized crime in general.

History

[edit]Origins: The Black Hand

[edit]

The first published account of what became the Mafia in the United States dates to the spring of 1869. The New Orleans Times reported that the city's Second District had become overrun by "well-known and notorious Sicilian murderers, counterfeiters and burglars, who, in the last month, have formed a sort of general co-partnership or stock company for the plunder and disturbance of the city."[citation needed] Emigration from southern Italy to the Americas was primarily to Brazil and Argentina, and New Orleans had a heavy volume of port traffic to and from both locales.

Mafia groups in the United States first became influential in the New York metropolitan area, gradually progressing from small neighborhood operations in poor Italian ghettos to citywide and eventually national organizations. "The Black Hand" was a name given to an extortion method used in Italian neighborhoods at the turn of the 20th century. It has been sometimes mistaken for the Mafia itself, which it is not. The Black Hand was a criminal society, but there were many small Black Hand gangs. Black Hand extortion was often (wrongly) viewed as the activity of a single organization, because Black Hand criminals in Italian communities throughout the United States used the same methods of extortion.[32]

Giuseppe Esposito was the first known Mafia member to emigrate to the United States.[28] He and six other Sicilians fled to New York after murdering eleven wealthy landowners, the chancellor and a vice-chancellor of a Sicilian province.[28] He was arrested in New Orleans in 1881 and extradited to Italy.[28]

From the 1890s to 1920 in New York City the Five Points Gang, founded by Paul Kelly, were very powerful in the Little Italy of the Lower East Side. Kelly recruited some street hoodlums who later became some of the most famous crime bosses of the century - such as Johnny Torrio, Al Capone, Lucky Luciano and Frankie Yale. They were often in conflict with the Jewish Eastmans of the same area. There was also an influential Mafia family in East Harlem. The Neapolitan Camorra was very active in Brooklyn. In Chicago, the 19th Ward was an Italian neighborhood that became known as the "Bloody Nineteenth" due to the frequent violence in the ward, mostly as a result of Mafia activity, feuds, and vendettas.

New Orleans was possibly the site of the first Mafia incident in the United States that received both national and international attention.[28] On October 15, 1890, New Orleans Police Superintendent David Hennessy was murdered execution-style. It is still unclear whether Italian immigrants actually killed him, or whether it was a frame-up by nativists against the reviled underclass immigrants.[28] Hundreds of Sicilians were arrested on mostly baseless charges, and nineteen were eventually indicted for the murder. An acquittal followed, with rumors of bribed and intimidated witnesses.[28] On March 14, 1891, after the acquittal, the outraged citizens of New Orleans organized a lynch mob and proceeded to kill eleven of the nineteen defendants. Two were hanged, nine were shot, and the remaining eight escaped.[33][34][35]

Prohibition era

[edit]On January 16, 1919, prohibition began in the United States with the 18th Amendment to the United States Constitution making it illegal to manufacture, transport, or sell alcohol. Despite these bans, there was still a very high demand for it from the public. This created an atmosphere that tolerated crime as a means to provide liquor to the public, even among the police and city politicians. While not explicitly related to Mafia involvement, the murder rate during the Prohibition era rose over 40% — from 6.8 per 100,000 individuals to 9.7 — and within the first three months succeeding the Eighteenth Amendment, a half-million dollars in bonded whiskey was stolen from government warehouses.[36] The profits that could be made from selling and distributing alcohol were worth the risk of punishment from the government, which had a difficult time enforcing prohibition. There were over 900,000 cases of liquor shipped to the borders of U.S. cities.[37] Criminal gangs and politicians saw the opportunity to make fortunes and began shipping larger quantities of alcohol to U.S. cities. The majority of the alcohol was imported from Canada,[38][39] the Caribbean, and the American Midwest where stills manufactured illegal alcohol.

In the early 1920s, fascist Benito Mussolini took control of Italy and waves of Italian immigrants fled to the United States. Sicilian Mafia members also fled to the United States, as Mussolini cracked down on Mafia activities in Italy.[40] Most Italian immigrants resided in tenement buildings. As a way to escape the poor lifestyle, some Italian immigrants chose to join the American Mafia.

The Mafia took advantage of prohibition and began selling illegal alcohol. The profits from bootlegging far exceeded the traditional crimes of protection, extortion, gambling, and prostitution. Prohibition allowed Mafia families to make fortunes.[41][42] As prohibition continued, victorious factions went on to dominate organized crime in their respective cities, setting up the family structure of each city. The bootlegging industry organized members of these gangs before they were distinguished as today's known families. The new industry required members at all different employment levels, such as bosses, lawyers, truckers, and even members to eliminate competitors through threat/force. Gangs hijacked each other's alcohol shipments, forcing rivals to pay them for "protection" to leave their operations alone, and armed guards almost invariably accompanied the caravans that delivered the liquor.[43][44]

In the 1920s, Italian Mafia families began waging wars for absolute control over lucrative bootlegging rackets. As the violence erupted, Italians fought Irish and Jewish ethnic gangs for control of bootlegging in their respective territories. In New York City, Frankie Yale waged war with the Irish American White Hand Gang. In Chicago, Al Capone and his family massacred the North Side Gang, another Irish American outfit.[45] In New York City, by the end of the 1920s, two factions of organized crime had emerged to fight for control of the criminal underworld — one led by Joe Masseria and the other by Salvatore Maranzano.[28] This caused the Castellammarese War, which led to Masseria's murder in 1931. Maranzano then divided New York City into five families.[28] Maranzano, the first leader of the American Mafia, established the code of conduct for the organization, set up the "family" divisions and structure, and established procedures for resolving disputes.[28] In an unprecedented move, Maranzano set himself up as boss of all bosses and required all families to pay tribute to him. This new role was received negatively, and Maranzano was murdered within six months on the orders of Charles "Lucky" Luciano. Luciano was a former Masseria underling who had switched sides to Maranzano and orchestrated the killing of Masseria.[46]

The Commission

[edit]

As an alternative to the previous despotic Mafia practice of naming a single Mafia boss as capo di tutti capi, or "boss of all bosses", Luciano created The Commission in 1931,[28] where the bosses of the most powerful families would have equal say and vote on important matters and solve disputes between families. This group ruled over the National Crime Syndicate and brought in an era of peace and prosperity for the American Mafia.[47] By mid-century, there were 26 official Commission-sanctioned Mafia crime families, each based in a different city (except for the Five Families which were all based in New York).[48] Each family operated independently from the others and generally had exclusive territory it controlled.[28] As opposed to the older generation of "Mustache Petes" such as Maranzano and Masseria, who usually worked only with fellow Italians, the "Young Turks" led by Luciano were more open to working with other groups, most notably the Jewish-American criminal syndicates to achieve greater profits. The Mafia thrived by following a strict set of rules that originated in Sicily that called for an organized hierarchical structure and a code of silence that forbade its members from cooperating with the police (Omertà). Failure to follow any of these rules was punishable by death.

The rise of power that the Mafia acquired during prohibition would continue long after alcohol was made legal again. Criminal empires which had expanded on bootleg money would find other avenues to continue making large sums of money. When alcohol ceased to be prohibited in 1933, the Mafia diversified its money-making criminal activities to include (both old and new): illegal gambling operations, loan sharking, extortion, protection rackets, drug trafficking, fencing, and labor racketeering through control of labor unions.[49] In the mid-20th century, the Mafia was reputed to have infiltrated many labor unions in the United States, most notably the Teamsters and International Longshoremen's Association.[28] This allowed crime families to make inroads into very profitable legitimate businesses such as construction, demolition, waste management, trucking, and in the waterfront and garment industry.[50] In addition they could raid the unions' health and pension funds, extort businesses with threats of a workers' strike and participate in bid rigging. In New York City, most construction projects could not be performed without the Five Families' approval. In the port and loading dock industries, the Mafia bribed union members to tip them off to valuable items being brought in. Mobsters would then steal these products and fence the stolen merchandise.

Meyer Lansky made inroads into the casino industry in Cuba during the 1930s while the Mafia was already involved in exporting Cuban sugar and rum.[51] When his friend Fulgencio Batista became president of Cuba in 1952, several Mafia bosses were able to make legitimate investments in legalized casinos. One estimate of the number of casinos mobsters owned was no less than 19.[51] However, when Batista was overthrown following the Cuban Revolution, his successor Fidel Castro banned U.S. investment in the country, putting an end to the Mafia's presence in Cuba.[51]

Las Vegas was seen as an "open city" where any family can work. Once Nevada legalized gambling, mobsters were quick to take advantage and the casino industry became very popular in Las Vegas. Since the 1940s, Mafia families from New York, Cleveland, Kansas City, Milwaukee and Chicago had interests in Las Vegas casinos. They got loans from the Teamsters' pension fund, a union they effectively controlled, and used legitimate front men to build casinos.[52] When money came into the counting room, hired men skimmed cash before it was recorded, then delivered it to their respective bosses.[52] This money went unrecorded, but the amount is estimated to be in the hundreds of millions of dollars.

Operating in the shadows, the Mafia faced little opposition from law enforcement. Local law enforcement agencies did not have the resources or knowledge to effectively combat organized crime committed by a secret society they were unaware existed.[50] Many people within police forces and courts were simply bribed, while witness intimidation was also common.[50] In 1951, a U.S. Senate committee called the Kefauver Hearings determined that a "sinister criminal organization" known as the Mafia operated in the nation.[28] Many suspected mobsters were subpoenaed for questioning, but few testified and none gave any meaningful information. In 1957, New York State Police uncovered a meeting and arrested major figures from around the country in Apalachin, New York. The event (dubbed the "Apalachin Meeting") forced the FBI to recognize organized crime as a serious problem in the United States and changed the way law enforcement investigated it.[28] In 1963, Joe Valachi became the first Mafia member to turn state's evidence, and provided detailed information of its inner workings and secrets. More importantly, he revealed the Mafia's existence to the law, which enabled the Federal Bureau of Investigation to begin an aggressive assault on the Mafia's National Crime Syndicate.[53] Following Valachi's testimony, the Mafia could no longer operate completely in the shadows. The FBI put a lot more effort and resources into organized crime activities nationwide and created the Organized Crime Strike Force in various cities. While all this created more pressure on the Mafia, it did little, however, to curb its criminal activities. Progress was made by the beginning of the 1980s, when the FBI was able to rid Las Vegas casinos of Mafia control and made a determined effort to loosen the Mafia's stronghold on labor unions.

The Mafia's involvement in the US economy

[edit]

By the late 1970s, the Mafia were involved in many industries,[28] including betting on college sports. Several Mafia members associated with the Lucchese crime family participated in a point shaving scandal involving the Boston College basketball team. Rick Kuhn, Henry Hill, and others associated with the Lucchese crime family, manipulated the results of the games during the 1978–1979 basketball season. Through bribing and intimidating several members of the team, they ensured their bets on the point spread of each game would go in their favor.[54]

One of the most lucrative gains for the Mafia was through gas-tax fraud. They created schemes to keep the money that they owed in taxes after the sale of millions of dollars' worth of wholesale petroleum. This allowed them to sell more gasoline at even lower prices. Michael Franzese, also known as the Yuppie Don, ran and organized a gas scandal and stole over $290 million in gasoline taxes by evading the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) and shutting down the gas station before government officials could make him pay what he owed. Franzese was caught in 1985.[55][56]

Labor racketeering helped the Mafia control many industries from a macroeconomic scale. This tactic helped them grow in power and influence in many cities with big labor unions such as New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, Detroit and many others. Many members of the Mafia were enlisted in unions and even became union executives. The Mafia has controlled unions all over the U.S. to extort money and resources out of big business, with recent indictments of corruption involving the New Jersey Waterfront Union, the Concrete Workers Union, and the Teamster Union.[57]

Restaurants were yet another powerful means by which the Mafia could gain economic power. A large concentration of Mafia-owned restaurants was in New York City. Not only were they the setting of many killings and important meetings, but they were also an effective means of smuggling drugs and other illegal goods. From 1985 to 1987, Sicilian Mafiosi in the U.S. imported an estimated $1.65 billion worth of heroin through pizzerias, hiding the cargo in various food products.[58][59]

Another one of the areas of the economy that the Mafia was most influential was Las Vegas, Nevada, beginning just after World War II with the opening of the first gambling resort, The Flamingo.[60] Many credit the Mafia with being a big part of the city's development in the mid-20th century,[61] as millions of dollars in capital flowing into new casino resorts laid the foundation for further economic growth. This capital did not come from one Mafia family alone, but many throughout the country seeking to gain even more power and wealth. Large profits from casinos, run as legitimate businesses, would help to finance many of the illegal activities of the Mafia from the 1950s into the 1980s.[60] In the 1950s more Mafia-financed casinos were constructed, such as the Stardust, Sahara, Tropicana, Desert Inn, and Riviera. Tourism in the city greatly increased through the 1960s and strengthened the local economy.

The 1960s were also when the Mafia's influence in the Las Vegas economy began to dwindle, however.[60] The Nevada State government and Federal government had been working to weaken Mafia activity on the Strip. In 1969, the Nevada State Legislature passed a law that made it easier for corporations to own casinos. This brought new investors to the local economy to buy casinos from the Mafia. The U.S. Congress passed the RICO Act a year later. This law gave more authority to law enforcement to pursue the Mafia for its illegal activities. There was a sharp decline in mob involvement in Las Vegas in the 1980s. Through the RICO law, many in the Mafia were convicted and imprisoned.[62]

The RICO Act

[edit]

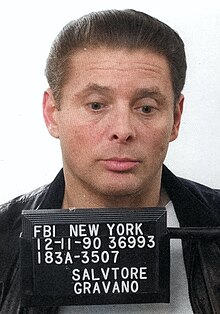

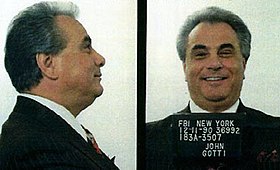

When the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO Act) became federal law in 1970, it became a highly effective tool in prosecuting mobsters. It provides for extended criminal penalties for acts performed as part of an ongoing criminal organization. Violation of the act is punishable by up to 20 years in prison per count, up to $25,000 in fines, and the violator must forfeit all properties attained while violating the RICO Act.[63] The RICO Act has proven to be a very powerful weapon because it attacks the entire corrupt entity instead of individuals who can easily be replaced with other organized crime members.[28] Between 1981 and 1992, 23 bosses from around the country were convicted under the law while between 1981 and 1988, 13 underbosses and 43 captains were convicted.[50] Over 1,000 crime family figures were convicted by 1990.[63] While this significantly crippled many Mafia families around the country, the most powerful families continued to dominate crime in their territories, even if the new laws put more mobsters in jail and made it harder to operate. A high-profile RICO case sentenced John Gotti and Frank Locascio to life in prison in 1992,[64] with the help of informant Sammy Gravano in exchange for immunity from prosecution for his crimes.[40][65]

Aside from avoiding long prison stretches, the FBI could put mobsters in the United States Federal Witness Protection Program, changing their identities and supporting them financially for life. This led to dozens of mobsters testifying and providing information during the 1990s, which led to the imprisonment of hundreds of other members. As a result, the Mafia has seen a major decline in its power and influence in organized crime since the 1990s.

On January 9, 2003, Bonanno crime family boss Joseph Massino was arrested and indicted, alongside Salvatore Vitale, Frank Lino and capo Daniel Mongelli, in a comprehensive racketeering indictment. The charges against Massino himself included ordering the 1981 murder of Dominick "Sonny Black" Napolitano.[66][67] Massino's trial began on May 24, 2004, with judge Nicholas Garaufis presiding and Greg D. Andres and Robert Henoch heading the prosecution.[68] He now faced 11 RICO counts for seven murders (due to the prospect of prosecutors seeking the death penalty for the Sciascia murder, that case was severed to be tried separately), arson, extortion, loansharking, illegal gambling, and money laundering.[69] After deliberating for five days, the jury found Massino guilty of all 11 counts on July 30, 2004. His sentencing was initially scheduled for October 12, and he was expected to receive a sentence of life imprisonment with no possibility of parole.[70] The jury also approved the prosecutors' recommended $10 million forfeiture of the proceeds of his reign as Bonanno boss on the day of the verdict.[71]

Immediately after his July 30 conviction, as court was adjourned, Massino requested a meeting with Judge Garaufis, where he made his first offer to cooperate.[72] He did so in hopes of sparing his life; he was facing the death penalty if found guilty of Sciascia's murder, as one of John Ashcroft's final acts as Attorney General was to order federal prosecutors to seek the death penalty for Massino.[73] Massino thus stood to be the first Mafia boss to be executed for his crimes, and the first mob boss to face the death penalty since Lepke Buchalter was executed in 1944.[74] Massino was the first sitting boss of a New York crime family to turn state's evidence, and the second in the history of the American Mafia to do so.[75] (Philadelphia crime family boss Ralph Natale had flipped in 1999 when facing drug charges, though Natale was mostly a "front" boss while the real boss of the Philadelphia Mafia used Natale as a diversion for authorities.)[76]

In the 21st century, the Mafia has continued to be involved in a broad spectrum of illegal activities. These include murder, extortion, corruption of public officials, gambling, infiltration of legitimate businesses, labor racketeering, loan sharking, tax fraud schemes and stock manipulation schemes.[77] Although the Mafia used to be nationwide, today most of its activities are confined to the Northeast and Chicago.[78] While other criminal organizations such as the Russian Mafia, Chinese Triads, Mexican drug cartels and others have all grabbed a share of criminal activities, the Mafia continues to be the dominant criminal organization in these regions, partly due to its strict hierarchical structure.[78] Law enforcement is concerned with the possible resurgence of the Mafia as it regroups from the turmoil of the 1990s, although FBI and local law enforcement agencies now focus more on homeland security and less on organized crime since the September 11 attacks.[79][80] To avoid FBI attention and prosecution, the modern Mafia also outsources much of its work to other criminal groups, such as motorcycle gangs.[78]

Structure

[edit]

The American Mafia operates on a strict hierarchical structure. While similar to its Sicilian origins, the American Mafia's modern organizational structure was created by Salvatore Maranzano in 1931. He created the Five Families, each of which would have a boss, an underboss, capos, and soldiers—all only of full-blooded Italian origin—while associates could come from any background.[81][82][40] All inducted members of the Mafia are called "made" men. This signifies that they are untouchable in the criminal underworld and any harm brought to them will be met with retaliation. With the exception of associates, all mobsters within the Mafia are "made" official members of a crime family. The three highest positions make up the administration. Below the administration, there are factions each headed by a caporegime (captain), who leads a crew of soldiers and associates. They report to the administration and can be seen as equivalent to managers in a business. When a boss makes a decision, he rarely issues orders directly to workers who would carry it out but instead passes instructions down through the chain of command. This way, the higher levels of the organization are insulated from law enforcement attention if the lower level members who actually commit the crime should be captured or investigated, providing plausible deniability.

There are occasionally other positions in the family leadership. Frequently, ruling panels have been set up when a boss goes to jail to divide the responsibility of the family (these usually consist of three or five members). This also helps divert police attention from any one member. The family messenger and street boss were positions created by former Genovese family leader Vincent Gigante.

- Boss – The boss is the head of the family, usually reigning as a dictator, sometimes called the Don or "Godfather". The boss receives a cut of every operation. Operations are taken on by every member of the family and of the region's occupying family.[83] Depending on the family, the boss may be chosen by a vote from the caporegimes of the family. In the event of a tie, the underboss must vote. In the past, all the members of a family voted on the boss, but by the late 1950s, any gathering such as that usually attracted too much attention.[84] In practice, many of these elections are seen as having an inevitable result, such as that of John Gotti in 1986. According to Sammy Gravano, a meeting was held in a basement during which all capos were searched and Gotti's men stood ominously behind them. Gotti was then proclaimed boss.

- Underboss – The underboss, usually appointed by the boss, is the second in command of the family. The underboss often runs the day-to-day responsibilities of the family or oversees its most lucrative rackets. He usually gets a percentage of the family's income from the boss's cut. The underboss is usually first in line to become acting boss if the boss is imprisoned, and is also frequently seen as a logical successor.

- Consigliere – The consigliere (counselor) is an advisor to the family and sometimes seen as the boss's "right-hand man". He is used as a mediator of disputes and often acts as a representative or aide for the family in meetings with other families, rival criminal organizations, and important business associates. In practice, the consigliere is normally the third-ranking member of the administration of a family and was traditionally a senior member carrying the utmost respect of the family and deeply familiar with the inner-workings of the organization. A boss will often appoint a trusted close friend or personal advisor as his official consigliere.

- Caporegime (or capo) – A caporegime (also captain or skipper) is in charge of a crew, a group of soldiers who report directly to him. Each crew usually contains 10–20 soldiers and many more associates. A capo is appointed by the boss and reports to him or the underboss. A captain gives a percentage of his (and his underlings') earnings to the boss and is also responsible for any tasks assigned, including murder. In labor racketeering, it is usually a capo who controls the infiltration of union locals. If a capo becomes powerful enough, he can sometimes wield more power than some of his superiors. In cases like that of Anthony Corallo, they might even bypass the normal Mafia structure and lead the family when the boss dies.

- Soldier (Soldato in Italian) – A soldato or "soldier" is an inducted (or "made") member of the Mafia in general and an inducted member of a particular Mafia crime family, and traditionally they can only be of full Italian background (although today many families require men to be of only half-Italian descent, on their father's side). Once a member is made he is untouchable, meaning permission from a soldier's boss must be given before he is murdered. When the books are open, meaning that a family is accepting new members, a made man may recommend an up-and-coming associate to be a new soldier. Soldiers are the main workers of the family, usually committing crimes like assault, murder, extortion, intimidation, etc. In return, they are given profitable rackets to run by their superiors and have full access to their family's connections and power.

- Associate – An associate is not a member of the Mafia, but works for a crime family nonetheless. Associates can include a wide range of people who work for the family. An associate can have a wide range of duties, from virtually carrying out the same duties as a soldier to being a simple errand boy. This is where prospective mobsters ("connected guys") start out to prove their worth. Once a crime family is accepting new members, the best associates of Italian descent are evaluated and picked to become soldiers. An associate can also be a criminal who serves as a go-between in criminal transactions or sometimes deals in drugs to keep police attention off the actual members, or they can simply be people the family does business with (restaurant owners, etc.) In other cases, an associate might be a corrupt labor union delegate or businessman.[84] Non-Italians will never go any further than this, although many non-Italian associates of the Mafia, such as Meyer Lansky, Murray Humphreys, Gus Alex, Gerard Ouimette and Jimmy Burke, wielded extreme power within their respective crime families and carried the respect of actual Mafia members.

Rituals and customs

[edit]The Mafia initiation ritual to become a "made man" in the Mafia emerged from various sources, such as Roman Catholic confraternities and Masonic Lodges in mid-19th century Sicily.[85] At the initiation ceremony, the inductee would have his finger pricked with a needle by the officiating member; a few drops of blood are spilled on a card bearing the likeness of a saint; the card is set on fire; finally, while the card is passed rapidly from hand to hand to avoid burns, the novice takes an oath of loyalty to the Mafia family. The oath of loyalty to the Mafia Family is called the Omerta. This was confirmed in 1986 by the pentito Tommaso Buscetta.[86]

A hit, or murder, of a made man must be approved by the leadership of his family, or retaliatory hits would be made, possibly inciting a war. In a state of war, families would "go to the mattresses," which means to prepare for a war or be prepared in a war-like stance. It was mainly derived from the film The Godfather, as the origin of the phrase is unknown.[87] Omertà is a key oath or code of silence in the Mafia that places importance on silence in the face of questioning by authorities or outsiders; non-cooperation with authorities, the government, or outsiders.[88][89] Traditionally, to become a made man, or full member of the Mafia, the inductee was required to be a male of full Sicilian descent,[90] later extended to males of full Italian descent,[91] and later further extended to males of half-Italian descent through their father's lineage.[90] According to Salvatore Vitale, it was decided during a Commission meeting in 2000 to restore the rule requiring both parents to be of Italian descent.[92] It is also common for a Mafia member to have a mistress.[93] Traditionally, made members were also not allowed to have mustaches—part of the Mustache Pete custom.[94][95] Homosexuality is reportedly incompatible with the American Mafia code of conduct. In 1992, John D'Amato, acting boss of the DeCavalcante family, was killed when he was suspected of engaging in homosexual activity.[96]

List of Mafia families

[edit]

The following is a list of Mafia families that have been active in the U.S. Note that some families have members and associates working in other regions as well. The organization is not limited to these regions. The Bonanno crime family and the Buffalo crime family also had influence in several factions in Canada including the Rizzuto crime family and Cotroni crime family,[97][98][99] and the Luppino crime family and Papalia crime family,[100][101] respectively.

- Bufalino crime family (Northeastern Pennsylvania)

- Chicago Outfit (Chicago, Illinois)

- Cleveland crime family (Cleveland, Ohio)

- Dallas crime family (Dallas, Texas)

- DeCavalcante crime family (Northern New Jersey)

- Denver crime family (Denver, Colorado)

- Detroit Partnership (Detroit, Michigan)

- The Five Families (New York, New York)

- Kansas City crime family (Kansas City, Missouri)

- Los Angeles crime family (Los Angeles, California)

- Magaddino crime family (Buffalo, New York)

- Milwaukee crime family (Milwaukee, Wisconsin)

- New Orleans crime family (New Orleans, Louisiana)

- Patriarca crime family (New England)

- Philadelphia crime family (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)

- Pittsburgh crime family (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania)

- Rochester crime family (Rochester, New York)

- San Francisco crime family (San Francisco, California)

- San Jose crime family (San Jose, California)

- Seattle crime family (Seattle, Washington)

- St. Louis crime family (St. Louis, Missouri)

- Trafficante crime family (Tampa, Florida)

Cooperation with the U.S. government

[edit]During World War II

[edit]U.S. Naval Intelligence entered into an agreement with Lucky Luciano to gain his assistance in keeping the New York waterfront free from saboteurs after the destruction of the SS Normandie.[103] This spectacular disaster convinced both sides to talk seriously about protecting the United States' East Coast on the afternoon of February 9, 1942. While it was in the process of being converted into a troopship, the luxury ocean liner, Normandie, mysteriously burst into flames with 1,500 sailors and civilians on board. All but one escaped, but 128 were injured and by the next day the ship was a smoking hull. In his report, twelve years later, William B. Herlands, Commissioner of Investigation, made the case for the U.S. government talking to top criminals, stating "The Intelligence authorities were greatly concerned with the problems of sabotage and espionage…Suspicions were rife with respect to the leaking of information about convoy movements. The Normandie, which was being converted to war use as the Navy auxiliary Lafayette, had burned at the pier in the North River, New York City. Sabotage was suspected."[104]

Plots to assassinate Fidel Castro

[edit]In August 1960, Colonel Sheffield Edwards, director of the Office of Security of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), proposed the assassination of Cuban head of state Fidel Castro by Mafia assassins. Between August 1960 and April 1961, the CIA, with the help of the Mafia, pursued a series of plots to poison or shoot Castro.[105] Those allegedly involved included Sam Giancana, Carlos Marcello, Santo Trafficante Jr., and John Roselli.[106]

Recovery of murdered Mississippi civil rights workers

[edit]In 2007, Linda Schiro testified in an unrelated court case that her late boyfriend, Gregory Scarpa, a capo in the Colombo family, had been recruited by the FBI to help find the bodies of three civil rights workers who had been murdered in Mississippi in 1964 by the Ku Klux Klan. She said that she had been with Scarpa in Mississippi at the time and had witnessed him being given a gun, and later a cash payment, by FBI agents. She testified that Scarpa had threatened a Klansman by placing a gun in the Klansman's mouth, forcing the Klansman to reveal the location of the bodies. Similar stories of Mafia involvement in recovering the bodies had been circulating for years, and had been previously published in the New York Daily News, but had never before been introduced in court.[107][108]

Law enforcement and the Mafia

[edit]In several Mafia families, killing a state authority is forbidden due to the possibility of extreme police retaliation. In some rare strict cases, conspiring to commit such a murder is punishable by death. Jewish mobster and Mafia associate Dutch Schultz was reportedly killed by his Italian peers out of fear that he would carry out a plan to kill New York City prosecutor Thomas Dewey and thus bring unprecedented police attention to the Mafia. However, the Mafia has carried out hits on law enforcement, especially in its earlier history. New York police officer Joe Petrosino was shot by Sicilian mobsters while on duty in Sicily. A statue of him was later erected across the street from a Lucchese hangout.[109]

Kefauver Committee

[edit]In 1951, a U.S. Senate special committee, chaired by Democratic Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver, determined that a "sinister criminal organization" known as the Mafia operated around the United States. The United States Senate Special Committee to Investigate Crime in Interstate Commerce (known as the "Kefauver Hearings"), televised nationwide, captured the attention of the American people and forced the FBI to recognize the existence of organized crime. In 1953, the FBI initiated the "Top Hoodlum Program". The purpose of the program was to have agents collect information on the mobsters in their territories and report it regularly to Washington to maintain a centralized collection of intelligence on racketeers.[110]

Apalachin meeting

[edit]The Apalachin meeting was a historic summit of the American Mafia held at the home of mobster Joseph "Joe the Barber" Barbara, at 625 McFall Road in Apalachin, New York, on November 14, 1957.[111][112] Allegedly, the meeting was held to discuss various topics including loansharking, narcotics trafficking, and gambling, along with dividing the illegal operations controlled by the recently murdered Albert Anastasia.[113][114] An estimated 100 Mafiosi from the United States, Italy, and Cuba are thought to have attended this meeting.[114] Immediately after the Anastasia murder that October, and after taking control of the Luciano crime family, renamed the Genovese crime family, from Frank Costello, Vito Genovese wanted to legitimize his new power by holding a national Cosa Nostra meeting. As a result of the Apalachin meeting, the membership books to become a made man in the mob were closed, and were not reopened until 1976.[115]

Local and state law enforcement became suspicious when numerous expensive cars bearing license plates from around the country arrived in what was described as "the sleepy hamlet of Apalachin".[116] After setting up roadblocks, the police raided the meeting, causing many of the participants to flee into the woods and area surrounding the Barbara estate.[117] More than 60 underworld bosses were detained and indicted following the raid. Twenty of those who attended the meeting were charged with "Conspiring to obstruct justice by lying about the nature of the underworld meeting" and found guilty in January 1959. All were fined, up to $10,000 each, and given prison sentences ranging from three to five years. All the convictions were overturned on appeal the following year.[why?] One of the most direct and significant outcomes of the Apalachin Meeting was that it helped to confirm the existence of a nationwide criminal conspiracy, a fact that some, including Federal Bureau of Investigation director J. Edgar Hoover, had long refused to acknowledge.[114][118][119]

Valachi hearings

[edit]Genovese crime family soldier Joe Valachi was convicted of narcotics violations in 1959 and sentenced to 15 years in prison.[120] Valachi's motivations for becoming an informer had been the subject of some debate: Valachi claimed to be testifying as a public service and to expose a powerful criminal organization that he had blamed for ruining his life, but it is also possible he was hoping for government protection as part of a plea bargain in which he was sentenced to life imprisonment instead of the death penalty for a murder, which he had committed in 1962 while in prison for his narcotics violation.[120]

Valachi murdered a man in prison who he feared mob boss, and fellow prisoner, Vito Genovese had ordered to kill him. Valachi and Genovese were both serving sentences for heroin trafficking.[121] On June 22, 1962, using a pipe left near some construction work, Valachi bludgeoned an inmate to death who he had mistaken for Joseph DiPalermo, a Mafia member who he believed had been contracted to kill him.[120] After time with FBI handlers, Valachi came forward with a story of Genovese giving him a kiss on the cheek, which he took as a "kiss of death".[122][123][124] A $100,000 bounty for Valachi's death had been placed by Genovese.[125]

Soon after, Valachi decided to cooperate with the U.S. Justice Department.[126] In October 1963, Valachi testified before Arkansas Senator John L. McClellan's Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations of the U.S. Senate Committee on Government Operations, known as the Valachi hearings, stating that the Italian-American Mafia actually existed, the first time a member had acknowledged its existence in public.[127][128] Valachi's testimony was the first major violation of omertà, breaking his blood oath. He was the first member of the Italian-American Mafia to acknowledge its existence publicly, and is credited with popularization of the term cosa nostra.[129]

Although Valachi's disclosures never led directly to the prosecution of any Mafia leaders, he provided many details of the history of the Mafia, operations and rituals, aided in the solution of several unsolved murders, and named many members and the major crime families. The trial exposed American organized crime to the world through Valachi's televised testimony.[130]

Commission Trial

[edit]As part of the Mafia Commission Trial, on February 25, 1985, nine New York Mafia leaders were indicted for narcotics trafficking, loansharking, gambling, labor racketeering and extortion against construction companies under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act.[131] On July 1, 1985, the original nine men, with the addition of two more New York Mafia leaders, pleaded not guilty to a second set of racketeering charges as part of the trial. Prosecutors aimed to strike at all the crime families at once using their involvement in the Commission.[132] On December 2, 1985, Gambino family underboss Neil Dellacroce died of cancer.[133] Gambino boss and de facto commission head Paul Castellano was later murdered on December 16, 1985.[134]

In the early 1980s, the Bonanno family were kicked off the Commission due to the Donnie Brasco infiltration, and although Rastelli was one of the men initially indicted, this removal from the Commission actually allowed Rastelli to be removed from the Commission Trial as he was later indicted on separate labor racketeering charges. Having previously lost their seat on the Commission, the Bonannos suffered less exposure than the other families in this case.[135][136]

Eight of the nine defendants were convicted of racketeering on November 19, 1986[137]— the exception, Anthony Indelicato, was convicted instead of the 1979 murder of Carmine Galante[138]— and all were sentenced on January 13, 1987.[139][140]

In the early 1990s, as the Colombo crime family war raged, the Commission refused to allow any Colombo member to sit on the Commission[141] and considered dissolving the family.

2011 indictments

[edit]On January 20, 2011, the United States Justice Department issued 16 indictments against Northeast American Mafia families resulting in 127 charged defendants[142] and more than 110 arrests.[143] The charges included murder, murder conspiracy, loansharking, arson, robbery, narcotics trafficking, extortion, illegal gambling and labor racketeering. It has been described as the largest operation against the Mafia in U.S. history.[144] Families that have been affected included the Five Families of New York as well as the DeCavalcante crime family of New Jersey and Patriarca crime family of New England.[145]

In popular culture

[edit]Film

[edit]The film Scarface (1932) is loosely based on the story of Al Capone.[146]

In 1968, Paramount Pictures released the film The Brotherhood starring Kirk Douglas as a Mafia don, which was a financial flop. Nevertheless, Paramount's production chief Robert Evans subsidized the completion of a Mario Puzo novel with similar themes and plot elements and bought the screen rights before completion.[147] Directed by Francis Ford Coppola, The Godfather became a huge success, both critically and financially (it won the Best Picture Oscar and for a year was the highest-grossing film ever made). It immediately inspired other Mafia-related films, including a direct sequel, The Godfather Part II (1974), also (partly) based on Puzo's novel, and yet another big winner at the Academy Awards, as well as films based on real Mafiosi like Honor Thy Father and Lucky Luciano (both in 1973) and Lepke and Capone (both in 1975).

Television

[edit]A 13-part miniseries by NBC called The Gangster Chronicles based on the rise of many major crime bosses of the 1920s and 1930s, aired in 1981.[148] The Sopranos was an award-winning HBO television show that depicted modern day American-Italian mob culture in New Jersey. Although the show is fictional, the general storyline is based on its creator David Chase's experiences growing up and interacting with New Jersey crime families.

Fat Tony in The Simpsons is described as "a mobster and the underboss of the Springfield Mafia".

Video games

[edit]The Mafia has been the subject of multiple crime-related video games. The Mafia series by 2K Czech and Hangar 13 consists of three games that follow the story of individuals who inadvertently become caught up with one or multiple fictional Mafia families while attempting to rise in their ranks or bring them down as revenge for something they did to them. The Grand Theft Auto series by Rockstar Games also features the Mafia prominently, mainly in the games set within the fictional Liberty City (based on New York); the games set in the "3D universe" canon feature the Forelli, Leone and Sindacco families, while those in the "HD universe" have the Ancelotti, Gambetti, Lupisella, Messina and Pavano families (a reference to the Five Families), as well as the less-influential Pegorino family. In all games, the different Mafia families serve as either employers or enemies to the player. In 2006, The Godfather was released, based on the 1972 film of the same name; it spawned a sequel, itself based on the film's sequel.

See also

[edit]- Atlantic City Conference

- The Corporation ("Cuban mafia")

- D-Company ("Indian mafia")

- Havana Conference

- Jewish-American organized crime

- Irish-American organized crime

- African-American organized crime

- La Eme ("Mexican Mafia")

- Timeline of organized crime

- Triad ("Chinese mafia")

- Unione Corse ("Corsican mafia")

- Yakuza ("Japanese mafia")

- Bratva ("Russian mafia")

- Sicilian Mafia

- Camorra

- Ndrangheta

- Sacra Corona Unita

Citations

[edit]- ^

- America's First Mafia War: New Orleans, 1868‑1872 Thomas Hunt and Martha Macheca Sheldon, The American Mafia (2008) Archived September 23, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- American Mafia Timeline Part 1. 1282-1899 Thomas Hunt, The American Mafia (2012) Archived June 7, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- The beginnings of America's Mafia in New Orleans Matt Haines, Very Local (February 4, 2020) Archived June 16, 2024, at archive.today

- ^ La Cosa Nostra in the United States James O. Finckenauer, National Institute of Justice (1999) Archived April 4, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Organized Crime". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- ^

- Crime 'Families' Taking Control of Pornography Ralph Blumenthal and Nicholas Gage, The New York Times (December 10, 1972) Archived November 11, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- Organized Crime Reaps Huge Profits From Dealing in Pornographic Films Nicholas Gage, The New York Times(October 12, 1975) Archived May 7, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Pornography and obscenity C. E. Casey and L. Martin, Office of Justice Programs (1978) Archived May 9, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- La Cosa Nostra in Drug Trafficking P. A. Lupsha, Office of Justice Programs (1987) Archived January 19, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- Prostitution and the Mafia: The Involvement of Organized Crime in the Global Sex Trade Sarah Shannon, Office of Justice Programs (1997) Archived November 29, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- La Cosa Nostra in the United States James O. Finckenauer, National Institute of Justice (1999) Archived April 4, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- "Organized Crime". Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on March 29, 2019. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- The Rise and Fall of Organized Crime in the United States James B. Jacobs, University of Chicago Press (2020) Archived July 8, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^

- Family Affairs: Two Mafia cases go to court Jacob V. Lamar Jr., Time (October 14, 1985) Archived January 15, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- Italy, U.S. target Mafia in massive raids NBC News (February 7, 2008) Archived February 28, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- The Case of the Exiled Mobsters Jeff Israely, Time (February 7, 2008) Archived July 25, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- Heroin & The 20th Century Detroit Mafia Scott Burnstein, GangsterReport.com (1 July 2014) Archived 19 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- "FBI and Italian police arrest 19 people in Sicily and US in mafia investigation". The Guardian. July 17, 2019. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- "Sicilia-Usa, i summit di mafia a Castellammare: casa di Domingo base per gli italoamericani". Giornale di Sicilia (in Italian). June 16, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2020. Archived June 17, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^

- Gomorrah: Italy's other Mafia p. 189 Roberto Saviano (2006) ISBN 978-0-374-16527-7

- I am Spartacus! – The Casalesi Clan & Maxi-Trials David Breakspear, nationalcrimesyndicate.com (April 27, 2020) Archived May 6, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^

- Gambino, Bonanno family members arrested in joint US-Italy anti-mafia raids Laura Smith-Spark and Hada Messia, CNN (February 12, 2014) Archived March 4, 2014, at the Wayback Machine

- "International mafia bust shows US-Italy crime links still strong". BBC News. November 11, 2023. Retrieved November 11, 2023. Archived November 11, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^

- The Mafia's Morality Crisis Jeffrey Goldberg, New York (January 9, 1995) Archived April 17, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Wanna-be mobster cops to 5 murders Helen Peterson, New York Daily News (September 15, 1998) Archived April 17, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Organized Crime in Chicago: Beyond the Mafia Robert M. Lombardo (2012) ISBN 9780252078781

- Chris Paciello ratted on mob bosses, new documents show Frank Owen, Miami New Times (March 8, 2012) Archived May 8, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- "Chicago mob bust; Grand Ave. Crew Takes a Hit". July 28, 2014. Archived from the original on July 9, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2019.

- Why War Horns May Sound Over Philly, Or Not… Pan American Crime (October 20, 2016) Archived November 15, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- Carmine Persico, Colombo Crime Family Boss, Is Dead at 85 Selwyn Raab, The New York Times (March 8, 2019) Archived December 3, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- End of an Era: Lucchese Underboss Gets Life in Prison Aliya Bashir, Westchester Magazine (September 23, 2020) Archived March 26, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- The Legacy of East Harlem’s Purple Gang Is One of Fear and Violence Tim Reynolds, Medium (October 12, 2023) Archived April 14, 2024, at archive.today

- ^

- New York Gang Reported to Sell Death and Drugs Howard Blum, The New York Times (December 16, 1977) Archived June 6, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- La Cosa Nostra – 1989 Report State of New Jersey Commission of Investigation (1989) Archived May 26, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- Sources: Mob Buys Coke From The JBM Kitty Caparella, Philadelphia Daily News (August 30, 1989)

- Heroin & The 20th Century Detroit Mafia Scott Burnstein, The Gangster Report (July 1, 2014) Archived October 19, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- Nicky Barnes, ‘Mr. Untouchable’ of Heroin Dealers, Is Dead at 78 Sam Roberts, The New York Times (June 8, 2019) Archived March 29, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Steel City Mafia: Blood, Betrayal and Pittsburgh’s Last Don Paul N. Hodos (2023) ISBN 9781467153751

- ^ Roots of the Armenian Power Gang Richard Valdemar, policemag.com (March 1, 2011) Archived March 27, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Organized Crime In Detroit: Forgotten But Not Gone". CBS Detroit. James Buccellato and Scott M. Burnstein. June 24, 2011. Retrieved May 18, 2016. Archived March 26, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^

- The French Connection—In Real Life Larry Collins and Dominique Lapierre, The New York Times (February 6, 1972) Archived October 19, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- The World: The Milieu of the Corsican Godfathers Time (September 4, 1972) Archived July 11, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- Heroin & The 20th Century Detroit Mafia Scott Burnstein, GangsterReport.com (1 July 2014) Archived 19 October 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dixie Mafia Russell McDermott, Texarkana Gazette (December 12, 2013) Archived April 4, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- ^

- Man Tied to Mafia Guilty on 10 Counts The New York Times (January 20, 1992) Archived April 9, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- The Man New York Daily News (October 12, 1994) Archived August 14, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- Greek Mob: Brotherly Mafia Love in Philly Nick Christophers, Greek Reporter (July 23, 2009) Archived March 8, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- ^

- The Cleveland Mafia: The end of an era and demise of a Don John Petkovic, The Plain Dealer (November 23, 2015) Archived August 7, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- Was There Anything Redeemable About Jewish Gangsters? Tabby Refael, Jewish Journal (June 30, 2022) Archived June 30, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Thibault, Eric (April 11, 2017). "La pègre libanaise alimentait les Hells Angels et la mafia". www.journaldemontreal.com. Retrieved April 11, 2017. Archived April 15, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- ^

- Soviet Emigre Mob Outgrows Brooklyn, and Fear Spreads Ralph Blumenthal and Celestine Bohlen, The New York Times (July 4, 1989) Archived September 22, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- Russia's New Export: The Mob James Rosenthal, The Washington Post (June 24, 1990) Archived April 15, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Former Lucchese Crime Boss Is to Testify on Russian Mob Selwyn Raab, The New York Times (May 15, 1996) Archived May 23, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- Code of Betrayal, Not Silence, Shines Light on Russian Mob Bill Berkeley, The New York Times (August 19, 2002) Archived February 29, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Feds: New York Mafia and Russian mob joined to lure women as strippers; arranged sham marriages Erica Pearson, Robert Gearty and Tracy Connor, New York Daily News (November 30, 2011) Archived February 25, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^

- How the Mob Is Affecting The County Elsa Brenner, The New York Times (June 23, 1996) Archived November 12, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- Who is Mileta Miljanić? The Serbian-American Drug Lord and Leader of ‘Group America’ occrp.org (March 15, 2021) Archived March 15, 2021, at the Wayback Machine

- ^

- 1986 Report of the Organized Crime Consulting Committee National Criminal Justice Reference Service p.7 (1986) Archived June 30, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs: Organized Crime on Wheels Phillip C. McGuire (1987)

- Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs USA Overview p. 13 United States Department of Justice (May 1991) Archived May 26, 2023, at the Wayback Machine

- Caparella, Kitty (March 11, 1999). "Mob-Pagan Pact: Joey's Bid For Philly Crime Boss Fueled By Link With Biker Gang". Philadelphia Daily News. Retrieved November 7, 2015. Archived 2016-01-02 at the Wayback Machine

- Barret, Devlin; Gardiner, Sean (January 21, 2011). "Structure Keeps Mafia Atop Crime Heap". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^

- A Mafia-Bloods Alliance Suzanne Smalley, Newsweek (December 20, 2007) Archived November 22, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Barry, Stephanie (December 28, 2019). "In our world, killing is easy': Latin Kings part of a web of organized crime alliances, say former gangsters and law enforcement officials". MassLive. Retrieved December 18, 2021. Archived February 4, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Capeci, Jerry (April 5, 2020). "Mafia scion John Gotti has ties to Latin Kings". NY Daily News. Retrieved December 18, 2021. Archived April 6, 2020, at the Wayback Machine

- ^

- On the trail of ‘Mad Dog’ Sullivan, Mafia hit man Ed Gold, The Villager (September 5, 2006) Archived August 10, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- The Life and Hard Times Of Cleveland's Mafia: How Danny Greene's Murder Exploded The Godfather Myth Cleveland Magazine (February 15, 2011) Archived July 7, 2017, at the Wayback Machine

- Beyond the 'Whitey' Bulger lore: 19 murder victims Ann O'Neill, CNN (June 27, 2011) Archived February 25, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- ^

- 6 Convicted of Racketeering After Muscling In on Mob Julie Preston, The New York Times (January 5, 2006) Archived March 24, 2024, at the Wayback Machine

- Sheehan, Kevin; Feuerherd, Ben (October 19, 2022). "Anthony Zottola convicted of plotting mob-associate dad Sylvester's murder, turns white as wife bursts into tears". Archived October 21, 2022, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b Albanese, Jay S. (2014). Paoli, Letizia (ed.). The Italian-American Mafia. Oxford University. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199730445.001.0001. ISBN 9780199730445.

- ^ a b Finckenauer, James O. "La Cosa Nostra in the United States" (PDF). ncjrs.gov. United Nations Archives. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 29, 2016. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Dickie, John (2015). Cosa Nostra: A History of the Sicilian Mafia. Macmillan. p. 5. ISBN 9781466893054. Retrieved August 5, 2016.

- ^ Mike Dash (2009). First Family. Random House. ISBN 9781400067220.

- ^ Roberto M. Dainotto (2015) The Mafia: A Cultural History pp.7-44 ISBN 9781780234434

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Italian Organized Crime". Organized Crime. Federal Bureau of Investigation. Archived from the original on October 10, 2010. Retrieved August 7, 2011.

- ^ Barrett, Devlin; Gardiner, Sean (January 22, 2011). "Structure Keeps Mafia Atop Crime Heap". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ Gardiner, Sean; Shallwani, Parvaiz (February 24, 2014). "Mafia Is Down—but Not Out". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on March 14, 2017. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ This etymology is based on the books Che cosa è la mafia? by Gaetano Mosca, Mafioso by Gaia Servadio, The Sicilian Mafia by Diego Gambetta, Mafia & Mafiosi by Henner Hess, and Cosa Nostra by John Dickie (see Books below).

- ^ "Sagepub.com" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 6, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2013.

- ^ Pontchartrain, Blake. "New Orleans Know-It-All". Bestofneworleans.com. Archived from the original on September 5, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ^ "Under Attack" Archived June 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. American Memory, Library of Congress. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ "1891 New Orleans prejudice and discrimination results in lynching of 11 Italians, the largest mass lynching in United States history" Archived February 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine, Milestones of the Italian American Experience, National Italian American Foundation. Retrieved February 26, 2010.

- ^ Abadinsky, Howard. Organized Crime. 7th ed. Belmont, California: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, 2003. pg. 67

- ^ Gervais, C.H, The Rum Runners: A Prohibition Scrapbook. 1980. Thornhill: Firefly Books. Pg 9

- ^ Phillip. Rum Running and the Roaring Twenties. 1995. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. Pg 16

- ^ Butts, Edward, Outlaws of The Lakes – Bootlegging and Smuggling from Colonial Times To Prohibition. 2004.Toronto: Linx Images Inc. Pg 110.

- ^ a b c Burrough, Bryan (September 11, 2005). "'Five Families': Made Men in America". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 23, 2015. Retrieved February 5, 2017.

- ^ Butts, Edward, Outlaws of The Lakes – Bootlegging and Smuggling from Colonial Times To Prohibition. 2004.Toronto: Linx Images Inc. Pg 109

- ^ Hallowell, Prohibition In Ontario, 1919-1923. 1972. Ottawa: Love Printing Service. Pg ix

- ^ Mason, Phillip. Rum Running and the Roaring Twenties. 1995. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. Pg 42

- ^ Butts, Edward, Outlaws of The Lakes – Bootlegging and Smuggling from Colonial Times To Prohibition. 2004.Toronto: Linx Images Inc. Pg 230

- ^ Gervais, C.H, The Rum Runners: A Prohibition Scrapbook. 1980. Thornhill: Firefly Books. Pg10

- ^ Cohen, Rich (1999). Tough Jews (1st Vintage Books ed.). New York: Vintage Books. pp. 65–66. ISBN 0-375-70547-3.

Genovese maranzano.

- ^ King of the Godfathers: Big Joey Massino and the Fall of the Bonanno Crime Family By Anthony M. DeStefano. Kensington Publishing Corp., 2008

- ^ "Rick Porrello's AmericanMafia.com – 26 Mafia Families and Their Cities". Americanmafia.com. Archived from the original on December 12, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ^ Dubro, James. Mob Rule – Inside the Canadian Mafia. 1985. Toronto: Macmillan of Canada. Pg, 277

- ^ a b c d Busting the Mob: United States v. Cosa Nostra James B. Jacobs, Christopher Panarella, Jay Worthington. NYU Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-8147-4230-3. pages 3–5

- ^ a b c Salinger, Lawrence M. (2005). Encyclopedia of white-collar & corporate crime: A – I, Volume 1. SAGE Publications. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-7619-3004-4. Retrieved August 10, 2011.

- ^ a b Mannion, James (2003). The Everything Mafia Book: True-Life Accounts of Legendary Figures, Infamous Crime Families, and Chilling Events. Everything series (illustrated ed.). Everything Books. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-58062-864-8.

- ^ "The Dying of the Light: The Joseph Valachi Story — Prologue — Crime Library on". Trutv.com. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ^ "ESPN Looks at How Boston College Helped Take Down 'Goodfellas'". Boston.com. October 7, 2014. Archived from the original on August 13, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ "Gas-tax Fraud Tied To Mob Families". tribunedigital-sunsentinel. Archived from the original on August 21, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ Raab, Selwyn (February 6, 1989). "Mafia-Aided Scheme Evades Millions in Gas Taxes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 12, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ^ Levin, Benjamin (2013). "American Gangsters: RICO, Criminal Syndicates, and Conspiracy Law as Market Control". periodical. SSRN 2002404.

- ^ Finckenauer, James O. (December 6, 2007). "United Nations Activities: La Cosa Nostra in the United States" (PDF). International Center National Institute of Justice. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 29, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2016.

- ^ "Gaetano Badalamenti, 80; Led Pizza Connection Ring (Obituary)". The New York Times. May 3, 2004.

- ^ a b c "Mafia in Las Vegas - The Mafia". the-mafia.weebly.com. Archived from the original on July 6, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ^ "Nevada's 20th century economy a tale of water, mining, casinos". Las Vegas Sun. January 3, 2000. Archived from the original on September 16, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ^ Jeff German (March 9, 2014). "From Siegel to Spilotro, Mafia influenced gambling, regulation in Las Vegas". Las Vegas Review-Journal. Archived from the original on June 30, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ^ a b Abadinsky, Howard. Organized Crime. 7th ed. Belmont, California: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, 2003. pg. 319

- ^ "United States of America, Appellee, v. Frank Locascio, and John Gotti, Defendants-Appellants". ispn.org. United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. October 8, 1993. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved March 9, 2012.

- ^ Sammy "The Bull" Gravano Archived November 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine By Allan May. TruTV

- ^ Rashbaum, William (January 10, 2003). "Reputed Boss Of Mob Family Is Indicted". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 18, 2014. Retrieved March 25, 2012.

- ^ Marzulli, John (January 10, 2003). "Top Bonanno Charged In '81 Mobster Rubout". New York Daily News. Archived from the original on January 3, 2014. Retrieved December 24, 2012.

- ^ Glaberson, William (May 25, 2004). "Grisly Crimes Described by Prosecutors as Mob Trial Opens". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved April 20, 2012.

- ^ Raab, p. 679

- ^ Glaberson, William (July 31, 2004). "Career of a Crime Boss Ends With Sweeping Convictions". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 16, 2014. Retrieved April 16, 2012.

- ^ DeStefano 2007, p. 312

- ^ DeStefano 2007, pp. 314–315

- ^ Glaberson, William (November 13, 2004). "Judge Objects to Ashcroft Bid for a Mobster's Execution". The New York Times. Retrieved April 21, 2012.

- ^ "'Last don' faces execution". The Guardian. Associated Press. November 13, 2004. Archived from the original on August 28, 2013. Retrieved April 3, 2013.

- ^ Raab, p. 688.

- ^ Braun, Stephen (May 4, 2001). "This Mob Shot Its Brains Out". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ "FBI — Italian/Mafia". Fbi.gov. Archived from the original on January 16, 2011. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ^ a b c Barret, Devlin; Gardiner, Sean (January 21, 2011). "Structure Keeps Mafia Atop Crime Heap". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on February 21, 2015. Retrieved January 22, 2011.

- ^ Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires by Selwyn Raab. 2005

- ^ Mafia is like a chronic disease, never cured Archived January 26, 2011, at the Wayback Machine By Edwin Stier. January 22, 2011

- ^ "A Chronicle of Bloodletting". Time. July 12, 1971. Archived from the original on February 4, 2013. Retrieved October 31, 2012.

- ^ Dash, Mike (2010). The First Family: Terror, Extortion, Revenge, Murder, and the Birth of the American Mafia. New York: Ballantine Books. pp. 384–386. ISBN 978-0345523570.

- ^ Abadinsky, Howard. Organized Crime. 7th ed. Belmont, California: Wadsworth/Thomson Learning, 2003.

- ^ a b Capeci, Jerry. The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Mafia. Indianapolis: Alpha Books, 2002

- ^ "Mafia's arcane rituals, and much of the organization's structure, were based largely on those of the Catholic confraternities and even Freemasonry, colored by Sicilian familial traditions and even certain customs associated with military-religious orders of chivalry like the Order of Malta." The Mafia Archived February 3, 2010, at the Wayback Machine from bestofsicily.com Archived May 16, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Lubasch, Arnold H. (October 30, 1985). "Admitted Member of Mafia Tells of Oath and Deadly Punishment". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 15, 2018. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ^ Martin, Gary. "'Go to the mattresses' - the meaning and origin of this phrase". Phrasefinder. Archived from the original on September 8, 2017. Retrieved November 8, 2017.

- ^ Reppetto, Thomas (January 28, 2005). Mafia: A history of its rise to power. Macmillan. ISBN 9780805077988. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ^ Raab, Selwyn (May 13, 2014). Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires. Macmillan. pp. 7–8. ISBN 9781429907989.

- ^ a b May, Allan. "Sammy "The Bull" Gravano". TruTV.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2008. Retrieved February 11, 2012.

- ^ Capeci, Jerry (January 19, 2005). "The Life, By the Numbers". NYMag.com. Archived from the original on April 28, 2017. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- ^ Raab, Selwyn (2005). Five Families: The Rise, Decline and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires. St. Martin Press. p. 704. ISBN 0-312-36181-5. Archived from the original on April 29, 2016. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ^ "Mafia wives: Married to the Mob". independent.co.uk. May 13, 2007. Archived from the original on April 10, 2017. Retrieved April 4, 2020.

- ^ Frankie Saggio and Fred Rosen. Born to the Mob: The True-Life Story of the Only Man to Work for All Five of New York's Mafia Families. 2004 Thunder's Mouth Press publishing. pg.12)

- ^ Making Jack Falcone: An Undercover FBI Agent Takes Down a Mafia Family. Pocket Star Books Publishing. September 29, 2009. p. 121. ISBN 9781439149911.

- ^ "Wiseguy Gets Life for Hit On Gay Mob Boss" Archived February 20, 2009, at the Wayback Machine by Thomas Zambito. New York Daily News, June 13, 2006

- ^ Lamothe, Lee; Humphreys, Adrian (May 12, 2009). The Sixth Family: The Collapse of the New York Mafia and the Rise of Vito Rizzuto. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 27–29. ISBN 9780470156933.

- ^ Auger and Edwards The Encyclopedia of Canadian Organized Crime p.63.

- ^ Capeci, Jerry (2004). The complete idiot's guide to the Mafia (2nd ed.). Indianapolis, IN: Alpha Books. ISBN 1-59257-305-3.

- ^ "Four charged in 2018 stabbing at mobster Nat Luppino's home". The Hamilton Spectator. Welland Tribune. May 2, 2019. Archived from the original on May 4, 2019. Retrieved May 4, 2019.

- ^ Schneider, Stephen (December 9, 2009). Iced: The Story of Organized Crime in Canada. John Wiley & Sons. p. 292. ISBN 9780470835005.

- ^ Devico, Peter J. (2007). The Mafia Made Easy: The Anatomy and Culture of la Cosa Nostra. Tate Pub & Enterprises Llc. p. 186. ISBN 9781602472549.

- ^ Tim Newark Mafia Allies, p. 288, 292, MBI Publishing Co., 2007 ISBN 978-0-7603-2457-8

- ^ Newark, Tim. "Pact With the Devil?". History Today Volume: 57 Issue: 4 2007. Archived from the original on April 22, 2014. Retrieved April 21, 2014.

- ^ Michael Evans. "Bay of Pigs Chronology, The National Security Archive (at The George Washington University)". Gwu.edu. Archived from the original on February 8, 2011. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ^ Ambrose & Immerman Ike's Spies, p. 303, 1999 ISBN 978-1-57806-207-2

- ^ Brick, Michael (October 30, 2007). "At Trial of Ex-F.B.I. Supervisor, How to Love a Mobster". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 10, 2009. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ "Witness: FBI used mob muscle to crack '64 case", NBC News, October 29, 2007. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ^ Five Families: The Rise, Decline, and Resurgence of America's Most Powerful Mafia Empires

- ^ "FBI — Using Intel to Stop the Mob, Pt. 2". Fbi.gov. October 1, 1963. Archived from the original on June 16, 2010. Retrieved January 26, 2011.

- ^ "Crime Inquiry Still Checking on Apalachin Meeting". Toledo Blade. Associated Press. July 2, 1958. pp. two. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ^ "Apalachin Meeting Ruled Against Gang Killing Of Tough, Probe Told". Schenectady Gazette. Associated Press. February 13, 1959. pp. 1, 3. Archived from the original on April 10, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ^ "Ex-Union Officers Take 5th On Mafia, Apalchin Meeting". Meriden Record. Associated Press. July 2, 1958. p. 1. Archived from the original on December 23, 2015.

- ^ a b c Blumenthal, Ralph (July 31, 2002). "For Sale, a House WithAcreage.Connections Extra;Site of 1957 Gangland Raid Is Part of Auction on Saturday". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ "Five Mafia Families Open Rosters to New Members". The New York Times. March 21, 1976. Archived from the original on April 6, 2020. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ^ "'Crime Meeting' Conspiracy Convictions Upset By Court". Lodi News-Sentinel. UPI. November 29, 1960. p. 2. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ^ "Host To Hoodlum Meet Dies Of Heart Attack". Ocala Star-Banner. Associated Press. June 18, 1959. p. 7. Retrieved May 27, 2012.

- ^ Sifakis, p. 19-20

- ^ Feder, Sid (June 11, 1959). "Old Mafia Myth Turns Up Again In Move Against Apalachin Mob". The Victoria Advocate. Retrieved June 2, 2012.

- ^ a b c "History of La Cosa Nostra". fbi.gov. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ Jerry Capeci. (2002) The Complete Idiot's Guide to the Mafia, Alpha Books. p. 200. ISBN 0-02-864225-2

- ^ Rudolf, Robert (1993). Mafia Wiseguys: The Mob That Took on the Feds. New York: SPI Books. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-56171-195-6.

- ^ Dietche, Scott M. (2009). The Everything Mafia Book: True-life accounts of legendary figures, infamous crime families, and nefarious deeds. Avon, Massachusetts: Adams Media. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-1-59869-779-7.

- ^ Kelly, G. Milton (October 1, 1963). "Valachi To Tell Of Gang War For Power". Warsaw Times-Union. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ^ "The rat who started it all; For 40 years, Joe Valachi has been in a Lewiston cemetery, a quiet end for the mobster who blew the lid off 'Cosa Nostra' when he testified before Congress in 1963". buffalonews.com. October 9, 2011. Archived from the original on October 2, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2020.

- ^ Adam Bernstein (June 14, 2006). "Lawyer William G. Hundley, 80". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 20, 2012. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ^ "Killers in Prison", Time, October 4, 1963. "Killers in Prison - TIME". Archived from the original on May 16, 2009. Retrieved January 23, 2020..

- ^ "The Smell of It", Time, October 11, 1963. ""The Smell of It" - TIME". Archived from the original on May 16, 2009. Retrieved January 23, 2020..

- ^ "Their Thing, Time, August 16, 1963". Archived from the original on May 14, 2009. Retrieved February 27, 2019.

- ^ Raab, Selwyn (2005). Five Families. New York: St. Martin's Press. pp. 135–136.

- ^ Lubasch, Arnold H. (February 27, 1985). "U.s. Indictment Says 9 Governed New York Mafia". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 19, 2019. Retrieved January 23, 2020.