Macbeth (1971 film)

| Macbeth | |

|---|---|

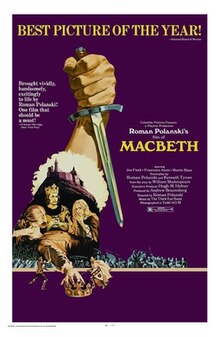

American theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Roman Polanski |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Tragedie of Macbeth by William Shakespeare |

| Produced by | Andrew Braunsberg |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Gil Taylor |

| Edited by | Alastair McIntyre |

| Music by | The Third Ear Band |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 140 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Language | English |

| Budget | $2.4 million (or £1.2 million)[2] |

| Box office | less than $1 million[3] |

Macbeth (also known as The Tragedy of Macbeth or Roman Polanski's Film of Macbeth) is a 1971 historical drama film directed by Roman Polanski, and co-written by Polanski and Kenneth Tynan. A film adaptation of William Shakespeare's tragedy of the same name, it tells the story of the Highland lord who becomes King of Scotland through treachery and murder. Jon Finch and Francesca Annis star as the title character and his wife, noted for their relative youth as actors. Themes of historic recurrence, greater pessimism and internal ugliness in physically beautiful characters are added to Shakespeare's story of moral decline, which is presented in a more realistic style.

Polanski opted to adapt Macbeth as a means of coping with the highly publicized Manson Family murder of his pregnant wife, Sharon Tate. Finding difficulty obtaining sponsorship from major studios, Playboy Enterprises stepped in to provide funding. Following troubled shooting around the British Isles mired by poor weather, Macbeth screened out of competition at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival and was a commercial failure in the United States. Initially controversial for its graphic violence and nudity, the film has since garnered generally positive reviews, and was named Best Film by the National Board of Review in 1972.

Plot

[edit]In the Middle Ages, a Norwegian and Irish invasion of Scotland aided by traitorous Thane of Cawdor, MacDonwald, is suppressed by Macbeth, Thane of Glamis, and Banquo. MacDonwald is sentenced to death by King Duncan and decrees Macbeth shall be awarded the title of Cawdor. Macbeth and Banquo do not hear of this news; when out riding, they happen upon Three Witches, who hail Macbeth as "Thane of Cawdor and future King", and Banquo as "lesser and greater". At their camp, nobles arrive and inform Macbeth he has been named the Thane of Cawdor, with Macbeth simultaneously awed and frightened at the prospect of usurping Duncan, in further fulfilment of the prophecy. He writes a letter to Lady Macbeth, who is delighted at the news. However, she fears her husband has too much good nature, and vows to be cruel for him. Duncan names his eldest son, Malcolm, Prince of Cumberland, and thus heir apparent, to the displeasure of Macbeth and Malcolm's brother Donalbain. The royal family and nobles then spend the night at Macbeth's castle, with Lady Macbeth greeting the King and dancing with him with duplicity.

Urged on by his wife, Macbeth steps into King Duncan's chambers after she has drugged the guards. Duncan wakes and utters Macbeth's name, but Macbeth stabs him to death. He frames the guards for the assassination and then murders them when Duncan's corpse is discovered. Fearing a conspiracy, Malcolm and Donalbain flee to England and Ireland, and the Thane of Ross realises Macbeth will be king. An opportunistic courtier, he hails Macbeth at Scone, while the noble Macduff heads back to his home in Fife. When Macbeth begins to fear possible usurpation by Banquo and his son Fleance, he sends two murderers to kill them, and then sends Ross as the mysterious Third Murderer. Banquo is killed, while Fleance escapes. Macbeth, disposes of the two murderers by drowning them. After Banquo appears at a banquet as a ghost, Macbeth seeks out the witches, who are performing a nude ritual. The witches and the spirits they summon deceive Macbeth into thinking he is invincible, as he cannot be killed except by a man not born of woman and will not be defeated until "Birnam Wood comes to Dunsinane."

Ross is sent to Fife to direct the slaughter of Macduff, however, Macduff has gone to England. Ross enters Fife castle pretending to be a friend, but leaves the heavy castle doors open, allowing Macbeth's gang of murderers in to kill Lady Macduff, the children and servants. With nobles fleeing Scotland, Macbeth chooses a new Thane of Fife, bestowing the title on Seyton over Ross. Disappointed, Ross leaves Scotland to join Malcolm and Macduff in England. They welcome him, unaware of his treachery. The English King has allied with Malcolm, committing forces led by Siward to overthrow Macbeth and install Malcolm on the Scottish throne.

The English forces invade, covering themselves by cutting down branches from Birnam Wood and holding them in front of their army to hide their numbers as they march on Macbeth in Dunsinane. When the forces storm the castle, Macduff confronts Macbeth, and during the sword fight, Macduff reveals he was delivered by Caesarean section. Macduff kills Macbeth by beheading him, and Ross presents the crown to Malcolm, who becomes the new King of Scotland. Meanwhile, Donalbain, out riding, encounters the witches.

Cast

[edit]- Jon Finch as Macbeth

- Francesca Annis as Lady Macbeth[4]

- Martin Shaw as Banquo[5]

- Terence Bayler as Macduff

- John Stride as Ross[5]

- Nicholas Selby as King Duncan[6]

- Stephan Chase as Malcolm

- Paul Shelley as Donalbain

- Maisie MacFarquhar as First Witch

- Elsie Taylor as Second Witch

- Noelle Rimmington as Third Witch

- Keith Chegwin as Fleance

- Diane Fletcher as Lady Macduff

- Mark Dightam as Macduff's son

- Bernard Archard as Angus

- Sydney Bromley as Porter

- Richard Pearson as Doctor

- Bruce Purchase as Caithness

- Ian Hogg as First Thane

- Michael Balfour as First Murderer

- Andrew McCulloch as Second Murderer

- Frank Wylie as Menteith

- Andrew Laurence as Lennox

- Noel Davis as Seyton

- Alf Joint as Young Siward

- William Hobbs as Young Siward

Themes and interpretations

[edit]

James Morrison wrote Macbeth's themes of "murderous ambition" fit in with Polanski's filmography,[7] and saw similarities to Orson Welles's 1948 film version of Macbeth in downplaying psychology and reviving the "primitive edge". However, unlike Welles, Polanski chooses naturalism over expressionism.[8] Author Ewa Mazierska wrote that, despite supposed realism in presenting soliloquies as voiceovers, Polanski's Macbeth was "absurdist", not depicting history as an explanation for current events, but as a "vicious circle of crimes and miseries". Each coronation occurs after the predecessor is violently dispatched, and guests and hosts always betray each other, with Polanski adding Ross leaving Fife's castle doors open.[9]

Deanne Williams read the film as not only Polanski's reflections on the murder of Sharon Tate, but on wider issues such as the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and the Vietnam War.[10] Francesca Royster similarly argues the use of English and Celtic cultures in the clothes and culture of the 1960s and 1970s, pointing to the publications of The Lord of the Rings in the U.S. and the music of Led Zeppelin, ties the film's past to the present.[11] While Playboy Enterprises role was mainly to provide funding, Williams also saw Polanski's Lady Macbeth as embodying "Playboy mythos" paradoxes, at times warm and sexy, at times a domestic servant, and at times femme fatale.[12]

In one scene, Macbeth's court hosts bear-baiting, a form of entertainment in the Middle Ages in which a bear and dogs are pitted against each other. Williams suggested the scene communicates Macbeth and Lady Macbeth's growing callousness after taking power,[13] while Kenneth S. Rothwell and Morrison matched the scene to Shakespeare's Macbeth describing himself as "bear-like".[14][15]

Literary critic Sylvan Barnet wrote that the younger protagonists suggested "contrast between a fair exterior and an ugly interior".[16] Williams compared Lady Macbeth to Lady Godiva in her "hair and naturalistic pallor", suggesting she could fit in at the Playboy Mansion.[12] More "ugliness" is added by Polanski in the re-imagining of Ross, who becomes a more important character in this film.[17] As with the leads, Ross demonstrates "evil-in-beauty" as he is played by "handsome John Stride".[18]

Barnet also wrote the changed ending with Donalbain meeting the witches replaced the message of "measure, time and place" with "unending treachery".[16] Film historian Douglas Brode also commented on the added ending, saying it reflected Polanski's pessimism in contradiction to Shakespeare's optimism. Likewise, Brode believed Macbeth's "Tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow" soliloquy becomes an articulation of nihilism in the film, while Shakespeare did not intend it to reflect his own sentiment.[19]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

Director Roman Polanski had been interested in adapting a Shakespeare play since he was a student in Kraków, Poland,[10] but he did not begin until after the murder of his pregnant wife, Sharon Tate, and three of the couple's mutual friends by members of the Manson Family at his house in Beverly Hills on the night of 9 August 1969. Following the murders, Polanski sank into deep depression, and was unhappy with the way the incident was depicted in the media, in which his films seemed to be blamed.[20] At the time, he was working on the film The Day of the Dolphin, a project that collapsed and was turned over to another director, Mike Nichols.[21] While in Gstaad, Switzerland during the start of 1970, Polanski envisioned an adaptation of Macbeth and sought out his friend, British theatre critic Kenneth Tynan, for his "encyclopedic knowledge of Shakespeare".[10] In turn, Tynan was interested in working with Polanski because the director demonstrated what Tynan considered "exactly the right combination of fantasy and violence". [22]

Around this time Richard Burton was discussing producing a version of Macbeth starring Elizabeth Taylor as Lady Macbeth from a script by Paul Dehn. "I'd rather put it together than appear in it," said Burton, adding "I'm not very confident getting it on in the present conditions in the film industry."[23]

Scripting

[edit]Tynan and Polanski found it challenging to adapt the text to suit the feel of the film. Tynan wrote to Polanski, saying, "the number one Macbeth problem is to see the events of the film from his point of view".[24] During the writing process, Polanski and Tynan acted out their scenes in a Belgravia, London apartment, with Tynan as Duncan and Polanski as Macbeth.[25] As with the 1948 film version of Hamlet, the soliloquies are presented naturalistically as voiceover narration.[24]

In one scene Polanski and Tynan wrote, Lady Macbeth delivers her sleepwalking soliloquy in the nude. Their decision was motivated by the fact that people in this era always slept in the nude.[26] Likewise, consultations of academic research of the Middle Ages led to the depiction of the nobles, staying at Macbeth's castle, going to bed on hay and the ground, with animals present.[27]

The added importance the film gives to Ross did not appear in the first draft of the screenplay, which instead invented a new character called the Bodyguard, who also serves as the Third Murderer.[18] The Bodyguard was merged into Shakespeare's Ross.[28] The screenplay was completed by August 1970, with plans to begin filming in England in October.[29]

Finance

[edit]Paramount Pictures, Universal Pictures and Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer declined to finance the project, seeing a Shakespeare play as a poor fit for a director who achieved success with Rosemary's Baby (1968).[30] Hugh Hefner, who published Playboy, had produced a few films with Playboy Enterprises and was eager to make more when he met Polanski at a party.[31] The budget was set at $2.4 million.[32]

Hefner's involvement was announced in August 1970. The Evening Standard reported "I understand that this new version will have a high content of sex and violence."[33]

In April 1971 Columbia Pictures announced they had signed a three-year deal with Playboy Enterprises to make at least four films together the first of which was Macbeth.[34]

Casting

[edit]

Due to a feeling that the characters of Macbeth were more relatable to young people in the 1960s than experienced, elder actors, Polanski deliberately sought out "young and good-looking" actors for the parts of Macbeth and Lady Macbeth.[35] Francesca Annis and Jon Finch were 26 and 29, respectively,[36] with Tynan remarking characters over 60 were too old to be ambitious.[35]

Polanski wanted to cast either Victoria Tennant or Tuesday Weld in the role of Lady Macbeth.[37] Weld rejected the role, unwilling to perform the nude scene.[36] The role was also turned down by Glenda Jackson who said "I don't fancy six weeks on location, walking through that damned gorse for next to no money."[38]

Casting of the role did not happen until just before the film started.[39] Annis accepted the role after some reluctance, as she agreed the character should be older, but was easy to persuade to join the cast.[35] Annais called the film "75 percent Shakespeare and 25 percent Polanski" saying "there is nothing to get excited about" her nude scene. "I simply walk across a room."[40]

Polanski's first choice for Macbeth was Albert Finney, who rejected the role, after which Tynan recommended Nicol Williamson, but Polanski felt he was not attractive enough.[36] Finch was better known for appearing in Hammer Film Productions pictures such as The Vampire Lovers and the television series Counterstrike.[35] Finch met Polanski on a Paris-London plane and auditioned several times.[41]

For the scene where the Three Witches and numerous others perform "Double, double, toil and trouble" in the nude, Polanski had difficulty hiring extras to perform. As a result, some of the witches are cut from cardboard.[12] Polanski had a few of the elderly extras sing "Happy Birthday to You" while naked for a video, sent to Hefner for his 45th birthday.[42]

Filming

[edit]

Macbeth was filmed in various locations around the British Isles, starting in Snowdonia in Wales in October 1970.[36][21] A considerable amount of shooting took place in Northumberland on the northeast coast of England, including Lindisfarne Castle, Bamburgh Castle and beach, St. Aidan's Church and North Charlton Moors near Alnwick.[43] Interior scenes were shot at Shepperton Studios;[37] filming started 2 November 1970.[44]

The production was troubled by poor weather,[45] and the cast complaining of Polanski's "petulance".[46] Fight director William Hobbs likened the long rehearsals in the rain to "training for the decathlon".[46]

Polanski personally handled and demonstrated the props and rode horses before shooting, and walked into animal feces to film goats and sheep.[46] It was common for the director to snatch the camera away from his cameramen.[47] He also decided to use special effects to present the "dagger of the mind", believing viewers may be puzzled or would not enjoy it if the dagger did not appear on screen, but was merely described in the dialogue.[48] The great challenges in portraying the catapult of fireballs into the castle led to Polanski calling it "special defects".[49]

By mid January the film was behind schedule. The completion guarantors arranged for Peter Collinson to be hired and filmed scenes in Shepperton.[50] [51]

Polanski justified the film's inefficiency, blaming "shitty weather", and agreed to give up one-third of the rest of his salary, on top of which Hefner contributed another $500,000 to complete the film.[52]

Music

[edit]For the film score, Polanski employed the Third Ear Band, a musical group which enjoyed initial success after publishing their album Alchemy in 1969. The band composed original music for the film, by adding electronic music to hand drums, woodwinds and strings.[26] Recorders and oboes were also used, inspired by Medieval music in Scotland.[53] Additionally, elements of music in India and the Middle East and jazz were incorporated into the score.[54]

In the scene where King Duncan is entertained as Macbeth's castle, lutes are played, and Fleance sings "Merciless Beauty" by Geoffrey Chaucer, though his lyrics did not fit the film's time frame.[55] While the score has some Middle Ages influence, this is not found in the scenes where Duncan is assassinated and Macbeth is killed. Polanski and the band used aleatoric music for these scenes, to communicate chaos.[26]

Release

[edit]In the United States, the film opened in the Playboy Theater in New York City on 20 December 1971.[56] Polanski bemoaned the release near January as "cinematic suicide" given usually low ticket sales for newly released films in that month.[24] The film opened in London in February 1972.[57] The film was screened at the 1972 Cannes Film Festival, but was not entered into the main competition.[58] Polanski, Finch and Annis attended the Cannes festival in May 1972.[59]

Box office

[edit]The film was a box office bomb.[45] According to The Hollywood Reporter, Playboy Enterprises estimated in September 1973 that it would lose $1.8 million on the film, and that it would damage the company as a whole.[60]

Total losses were $3.5 million.[61] The losses caused Shakespeare films to appear commercially risky until Kenneth Branagh directed Henry V in 1989.[62] Film critic Terrence Rafferty associated the financial failure with the various superstitions surrounding the play.[24]

Critical reception

[edit]Upon release, Macbeth received mixed reviews, with much negative attention on its violence, in light of the Manson murders, and the nudity, blamed on its Playboy associations.[24] Pauline Kael wrote the film "reduces Shakespeare's meanings to the banal theme of 'life is a jungle'".[63] Variety staff dismissed the film, writing, "Does Polanski's Macbeth work? Not especially, but it was an admirable try".[64] Derek Malcolm, writing for The Guardian, called the film shocking but not over-the-top, and Finch and Annis "more or less adequate".[57]

In contrast, Roger Ebert gave it four stars, writing it was "full of sound and fury" and "All those noble, tragic Macbeths – Orson Welles and Maurice Evans and the others – look like imposters now, and the king is revealed as a scared kid".[65] Roger Greenspun, for The New York Times, said that despite gossip about the film, it is "neither especially nude nor unnecessarily violent", and that Finch and Annis give great performances.[56] In New York, Judith Crist defended the film as traditional, appropriately focusing on Macbeth's "moral deterioration", and suited for youthful audiences, and drew parallel with its blood to the title of Akira Kurosawa's 1957 Macbeth film, Throne of Blood.[66]

Literary critic Sylvan Barnet wrote that, given Shakespeare's writing, it was arguable "blood might just as well flow abundantly in a film". However, he wrote the perceived inspiration from the Theatre of Cruelty is "hard to take".[16] Troy Patterson, writing for Entertainment Weekly, gave the film a B, calling it "Shakespeare as fright show" and Annis a better fit for Melrose Place.[67] The Time Out review states the realistic acting did not do justice to the poetry, and the film "never quite spirals into dark, uncontrollable nightmare as the Welles version (for all its faults) does".[68]

Opinions improved with time, with filmmaker and novelist John Sayles saying, "I think it's a great piece of filmmaking" in 2007, and novelist Martin Amis saying, "I really think the film is without weaknesses" in 2013.[24] In his 2014 Movie Guide, Leonard Maltin gave the film three and a half stars, describing it as "Gripping, atmospheric and extremely violent".[69] The film holds an 80% rating on the review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes, based on 64 reviews, with the consensus "Roman Polanski's Macbeth is unsettling and uneven, but also undeniably compelling."[70]

Accolades

[edit]| Award | Date of ceremony | Category | Recipient(s) | Result | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| British Academy Film Awards | 28 February 1973 | Anthony Asquith Award for Film Music | Third Ear Band | Nominated | [71] |

| Best Costume Design | Anthony Mendleson (also for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Young Winston) | Won | |||

| National Board of Review | 3 January 1972 | Best Film | Macbeth | Won | [72] |

| Top Ten Films | Won |

Home media

[edit]After a restoration by Sony Pictures Entertainment, the film was placed in the Venice Classics section in the 2014 Venice Film Festival.[73] In Region 1, The Criterion Collection released the film on DVD and Blu-ray in September 2014.[45]

References

[edit]- ^ "Macbeth (AA)". British Board of Film Classification. 27 October 1971. Retrieved 30 November 2016.

- ^ Chapman, J. (2022). The Money Behind the Screen: A History of British Film Finance, 1945-1985. Edinburgh University Press p 265.

- ^ Sandford p 182

- ^ Ain-Krupa 2010, pp. 78–79.

- ^ a b Mazierska 2007, p. 201.

- ^ Shakespeare 2004, p. xxxv.

- ^ Morrison 2007, p. 113.

- ^ Morrison 2007, p. 116.

- ^ Mazierska 2007, p. 149.

- ^ a b c Williams 2008, p. 146.

- ^ Royster 2016, pp. 176–177.

- ^ a b c Williams 2008, p. 153.

- ^ Williams 2008, p. 151.

- ^ Rothwell 2008, p. 254.

- ^ Morrison 2007, p. 115.

- ^ a b c Barnet 1998, p. 198.

- ^ Kliman 1998, pp. 137–138.

- ^ a b Kliman 1998, p. 138.

- ^ Brode 2000, p. 192.

- ^ Ain-Krupa 2010, p. 78.

- ^ a b Ain-Krupa 2010, p. 79.

- ^ Sandford 2007, p. 207.

- ^ Edwards, Sydney (26 September 1970). "Burton in the bargain basement". Evening Chronicle. p. 16.

- ^ a b c d e f Rafferty, Terrence (24 September 2014). "Macbeth: Something Wicked". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ Williams 2008, p. 145.

- ^ a b c Williams 2008, p. 152.

- ^ Mazierska 2007, p. 151.

- ^ Kliman 1998, p. 139.

- ^ Weiler, A.H. (16 August 1970). "Film: Polanski, Tynan and 'Macbeth'". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ Sandford 2007, p. 208.

- ^ Brode 2000, p. 189.

- ^ Rothwell 2004, p. 147.

- ^ Owen, Michael (21 August 1970). "Henfer to film Macbeth". Evening Standard. p. 9.

- ^ Cooper, Rod (24 April 1971). "Playboy-Columbia deal". Kine Weekly. p. 14.

- ^ a b c d Williams 2008, p. 147.

- ^ a b c d Sandford 2007, p. 212.

- ^ a b "The Tragedy of Macbeth". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved 3 December 2021.

- ^ Woodward, Ian (1985). Glenda Jackson : a study in fire and ice. St. Martin's Press. p. 79. ISBN 9780312329143.

- ^ "Francesca the likely Lady Mabeth". Evening Standard. 3 November 1970. p. 9.

- ^ "Nudity didn't stop Francesca playing in Macbeth". Evening Sentinel. 19 June 1971. p. 4.

- ^ Nisse, Neville (25 November 1971). "Young man going places fast". Grimsby Evening Telegraph. p. 11.

- ^ Sandford 2007, p. 215.

- ^ "Macbeth". BBC Tyne. Retrieved 18 April 2006.

- ^ Owen, Michael (27 October 1970). "Macbeth film role goes to 'unknown'". Evening Standard. p. 17.

- ^ a b c Ng, David (23 September 2014). "Roman Polanski's 'Macbeth' revisited by Criterion Collection". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ a b c Sandford 2007, p. 213.

- ^ Sandford 2007, p. 214.

- ^ Brode 2000, p. 188.

- ^ Williams 2008, p. 150.

- ^ Sandford 2007, p. 219.

- ^ Tynan, Kenneth (1976). The sound of two hands clapping. Holt, Rinehart and Winston. p. 87. ISBN 9780030167263.

- ^ Sandford 2007, p. 220.

- ^ Leonard 2009, p. 84.

- ^ Sandford 2007, p. 222.

- ^ Leonard 2009, p. 85.

- ^ a b Greenspun, Roger (21 December 1971). "Film: Polanski's and Tynan's 'Macbeth'". The New York Times. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ a b Malcolm, Derek (3 February 1972). "Throne of blood". The Guardian. p. 10.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Macbeth". festival-cannes.com. Archived from the original on 8 March 2012. Retrieved 17 April 2009.

- ^ Sandford 2007, pp. 227–228.

- ^ "The Tragedy of Macbeth (1971)". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved 8 December 2016.

- ^ Monaco 1992, p. 508.

- ^ Crowl 2010.

- ^ Kael 1991, p. 444.

- ^ Staff (31 December 1971). "Macbeth". Variety. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (1 January 1971). "Macbeth". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ Crist, Judith (10 January 1972). "Some Late Bloomers, and a Few Weeds". New York. p. 56.

- ^ Patterson, Troy (10 May 2002). "MacBeth". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ TM (10 September 2012). "Macbeth (1971)". Time Out. Retrieved 9 December 2016.

- ^ Maltin 2013.

- ^ "Macbeth (1971)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ "Film in 1973". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ "1971 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved 6 December 2016.

- ^ Barraclough, Leo (15 July 2014). "'Guys and Dolls' Joins Venice Classics Line-up". Variety. Retrieved 30 January 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]- Ain-Krupa, Julia (2010). Roman Polanski: A Life in Exile. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-Clio. ISBN 978-0313377808.

- Barnet, Sylvan (1998). "Macbeth on Stage and Screen". Macbeth. A Signet Classic. ISBN 9780451526779.

- Brode, Douglas (2000). Shakespeare in the Movies: From the Silent Era to Shakespeare in Love. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019972802X.

- Crowl, Samuel (2010). "Flamboyant Realist: Kenneth Branagh". The Cambridge Companion to Shakespeare on Film. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1107495302.

- Ilieş Gheorghiu, Oana. (2011). "Cathartic Violence. Lady Macbeth and Feminine Power in Roman Polanski's Macbeth (1971)". Europe's Times and Unknown Waters Cluj-Napoca.

- Kael, Pauline (1991). 5001 Nights at the Movies. New York City: Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 0805013679.

- Kliman, Bernice W. (1998). "Gleanings: The Residue of Difference in Scripts: The Case of Polanski's Macbeth". In Halio, Jay L.; Richmond, Hugh M. (eds.). Shakespearean Illuminations: Essays in Honor of Marvin Rosenberg. Newark: University of Delaware Press. pp. 131–146. ISBN 0874136571.

- Leonard, Kendra Preston (2009). Shakespeare, Madness, and Music: Scoring Insanity in Cinematic Adaptations. Lanham, Toronto and Plymouth: The Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810869585.

- Maltin, Leonard (2013). Leonard Maltin's 2014 Movie Guide. A Signet Book.

- Mazierska, Ewa (2007). Roman Polanski: The Cinema of a Cultural Traveller. New York City: IB Tauris and Co Ltd. ISBN 978-1845112967.

- Monaco, James (1992). The Movie Guide. New York: Baseline Books. ISBN 0399517804.

- Morrison, James (2007). Roman Polanski. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0252074462.

- Rothwell, Kenneth S. (2004). A History of Shakespeare on Screen: A Century of Film and Television (Second ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521543118.

- Rothwell, Kenneth S. (2008). "Classic Film Versions". A Companion to Shakespeare's Works, Volume I: The Tragedies. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 978-0470997277.

- Royster, Francesca (2016). "Riddling Whiteness". Weyward Macbeth: Intersections of Race and Performance. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0230102163.

- Sandford, Christopher (2007). Polanski. Random House. ISBN 978-1446455562.

- Shakespeare, William (2004). Bevington, David; Scott Kastan, David (eds.). Macbeth: The New Bantam Shakespeare. New York City: Bantam Dell, division of Random House.

- Williams, Deanne (2008). "Mick Jagger Macbeth". Shakespeare Survey: Volume 57, Macbeth and Its Afterlife: An Annual Survey of Shakespeare Studies and Production. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521841207.

External links

[edit]- Macbeth at IMDb

- Macbeth at Rotten Tomatoes

- Macbeth at Letterboxd

- Macbeth at TCMDB

- Macbeth: Something Wicked an essay by Terrence Rafferty at The Criterion Collection

- 1971 films

- 1970s historical drama films

- American historical drama films

- British historical drama films

- Films based on Macbeth

- Films directed by Roman Polanski

- Films set in castles

- Films shot in England

- Films shot in Wales

- Playboy Productions films

- Films with screenplays by Roman Polanski

- 1971 drama films

- Films set in medieval Scotland

- Films shot in Northumberland

- Films shot at Shepperton Studios

- 1970s English-language films

- 1970s American films

- 1970s British films

- English-language historical drama films