History of Macau

| This article is part of a series on the |

| History of Macau |

|---|

|

| Other Macau topics |

| History of China |

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Macau |

|---|

|

| History |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Sport |

Macau is a special administrative region (SAR) of the People's Republic of China. It was leased to Portugal in 1557 as a trading post in exchange for a symbolic annual rent of 500 tael. Despite remaining under Chinese sovereignty and authority, the Portuguese came to consider and administer Macau as a de facto colony. Following the signing of the Treaty of Nanking between China and Britain in 1842, and the signing of treaties between China and foreign powers during the 1860s, establishing the benefit of "the most favoured nation" for them, the Portuguese attempted to conclude a similar treaty in 1862, but the Chinese refused, owing to a misunderstanding over the sovereignty of Macau. In 1887 the Portuguese finally managed to secure an agreement from China that Macau was Portuguese territory.[1] In 1999 it was handed over to China. Macau was the last extant European territory in continental Asia.

Early history

[edit]The human history of Macau stretches back up to 6,000 years, and includes many different and diverse civilisations and periods of existence. Evidence of human and culture dating back 3,500 to 4,000 years has been discovered on the Macau Peninsula on Coloane Island.[2]

During the Qin dynasty (221–206 BC), the region was under the jurisdiction of Panyu County, Nanhai Prefecture of the province of Guangdong.[3][4][5] The region is first known to have been settled during the Han dynasty.[6] It was administratively part of Dongguan Prefecture in the Jin dynasty (266–420 AD), and alternated under the control of Nanhai and Dongguan in later dynasties.[5][7]

Since the 5th century, merchant ships travelling between Southeast Asia and Guangzhou used the region as a port for refuge, fresh water, and food.[8] In 1152, during the Song dynasty (960–1279 AD), it was under the jurisdiction of the new Xiangshan County.[3][4][7] In 1277, approximately 50,000 refugees fleeing the Mongol conquest of China settled in the coastal area.[5][7][9]

Mong Há has long been the centre of Chinese life in Macau and the site of what may be the region's oldest temple, a shrine devoted to the Buddhist Guanyin (Goddess of Mercy).[10] Later in the Ming dynasty (1368–1644 AD), fishermen migrated to Macau from various parts of Guangdong and Fujian provinces and built the A-Ma Temple where they prayed for safety on the sea. The Hoklo Boat people were the first to show interest in Macau as a trading centre for the southern provinces. However, Macau did not develop as a major settlement until the Portuguese arrived in the 16th century.[9]

Portuguese settlement

[edit]

During the age of discovery Portuguese sailors explored the coasts of Africa and Asia. The sailors later established posts at Goa in 1510, and conquered Malacca in 1511, driving the Sultan to the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula from where he kept making raids on the Portuguese. The Portuguese under Jorge Álvares landed at Lintin Island in the Pearl River Delta of China in 1513 with a hired junk sailing from Portuguese Malacca. They erected a stone marker at Lintin Island claiming it for the King of Portugal, Manuel I. In the same year, the Indian Viceroy Afonso de Albuquerque commissioned Rafael Perestrello — a cousin of Christopher Columbus – to sail to China in order to open up trade relations. Rafael traded with the Chinese merchants in Guangzhou in that year and in 1516, but was not allowed to move further.

Portugal's king Manuel I in 1517 commissioned a diplomatic and trade mission to Guangzhou headed by Tomé Pires and Fernão Pires de Andrade. The embassy lasted until the death of the Zhengde Emperor in Nanjing. The embassy was further rejected by the Chinese Ming court, which now became less interested in new foreign contacts. The Ming Court was also influenced by reports of misbehaviour of Portuguese elsewhere in China, and by the deposed Sultan of Malacca seeking Chinese assistance to drive the Portuguese out of Malacca.

In 1521 and 1522 several more Portuguese ships reached the trading island Tamão off the coast near Guangzhou, but were driven away by the now-hostile Ming authorities. Pires was imprisoned and died in Canton.

In their first attempts at obtaining trading posts by force, the Portuguese were defeated by the Ming Chinese at the Battle of Tunmen in Tamão or Tuen Mun in 1521 where the Portuguese lost two ships, and Battle of Sincouwaan in Lantau Island where the Portuguese also lost two ships, and Shuangyu in 1548 where several Portuguese were captured and near the Dongshan Peninsula in 1549, where two Portuguese junks and Galeote Pereira were captured. During these battles the Ming Chinese captured weapons from the defeated Portuguese which they then reverse engineered and mass-produced in China such as matchlock musket arquebuses which they named bird guns and Breech loading swivel guns which they named as Folangji (Frankish) cannon because the Portuguese were known to the Chinese under the name of Franks at this time. The Portuguese later returned to China peacefully and presented themselves under the name Portuguese instead of Franks in the Luso-Chinese agreement (1554) and rented Macau as a trading post from China by paying annual lease of hundreds of silver taels to Ming China.[11]

Good relations between the Portuguese and Chinese Ming dynasty resumed in the 1540s, when the Portuguese aided China in eliminating coastal pirates. The two later began annual trade missions to the offshore Shangchuan Island in 1549. A few years later, Lampacau Island, closer to the Pearl River Delta, became the main base of the Portuguese trade in the region.[12]

Diplomatic relations were further improved and salvaged by the Leonel de Sousa agreement with Cantonese authorities in 1554. In 1557, the Ming court finally gave consent for a permanent and official Portuguese trade base at Macau. In 1558, Leonel de Sousa became the second Portuguese governor of Macau.

They later built some rudimentary stone-houses around the area now called Nam Van. But not until 1557 did the Portuguese establish a permanent settlement in Macau, at an annual rent of 500 taels (~20 kilograms (44 lb)) of silver.[13] Later that year, the Portuguese established a walled village there. Ground rent payments began in 1573. China retained sovereignty and Chinese residents were subject to Chinese law, but the territory was under Portuguese administration. In 1582 a land lease was signed, and annual rent was paid to Xiangshan County.[citation needed] The Portuguese continued to pay an annual tribute up to 1863 in order to stay in Macau.[14]

The Portuguese often married Tanka women since Han Chinese women would not have relations with them. Some of the Tanka's descendants became Macanese people. Some Tanka children were enslaved by Portuguese raiders.[15] The Chinese poet Wu Li wrote a poem, which included a line about the Portuguese in Macau being supplied with fish by the Tanka.[16][17][18][19]

Macau's golden age

[edit]

Both Chinese and Portuguese merchants flocked to Macau, although the Portuguese were never numerous (numbering just 900 in 1583 and 1200 out of 26,000 in 1640).[20] It quickly became an important node in the development of Portugal's trade along three major routes: Macau–Malacca–Goa–Lisbon, Guangzhou–Macau–Nagasaki and Macau–Manila–Mexico. The Guangzhou–Macau–Nagasaki route was particularly profitable because the Portuguese acted as middlemen, shipping Chinese silks to Japan and Japanese silver to China, pocketing huge markups in the process. This already lucrative trade became even more so when Chinese officials handed Macau's Portuguese traders a monopoly by banning direct trade with Japan in 1547, due to piracy by Chinese and Japanese nationals.[21]

In 1637, An English explorer John Weddell arrived at Macau.[22]

Macau's golden age coincided with the union of the Spanish and Portuguese crowns, between 1580 and 1640. King Philip II of Spain was encouraged to not harm the status quo, to allow trade to continue between Portuguese Macau and Spanish Manila, and to not interfere with Portuguese trade with China. In 1587, Philip promoted Macau from "Settlement or Port of the Name of God" to "City of the Name of God" (Cidade do Nome de Deus de Macau).[23]

The alliance of Portugal with Spain meant that Portuguese colonies became targets for the Netherlands, which was embroiled at the time in a lengthy struggle for its independence from Spain, the Eighty Years' War. After the Dutch East India Company was founded in 1602, the Dutch unsuccessfully attacked Macau several times, culminating in a full-scale invasion attempt in 1622, when 800 attackers were successfully repelled by 150 Macanese and Portuguese defenders and a large number of African slaves.[24] One of the first actions of Macau's next governor, who arrived the following year, was to strengthen the city's defences, which included the construction of the Guia Fortress.[25]

Religious activity

[edit]As well as being an important trading post, Macau was a centre of activity for Catholic missionaries, as it was seen as a gateway for the conversion of the vast populations of China and Japan. Jesuits had first arrived in the 1560s and were followed by Dominicans in the 1580s. Both orders soon set about constructing churches and schools, the most notable of which were the Jesuit Cathedral of Saint Paul and the St. Dominic's Church built by the Dominicans. In 1576, Macau was established as an episcopal see by Pope Gregory XIII with Melchior Carneiro appointed as the first bishop.[26][27]

1637–1844: Decline

[edit]

In 1637, increasing suspicion of the intentions of Spanish and Portuguese Catholic missionaries in Japan finally led the shōgun to seal Japan off from foreign influence. Later named the sakoku period, this meant that no Japanese were allowed to leave the country (or return if they were living abroad), and no foreign ship was allowed to dock in a Japanese port. An exception was made for the Protestant Dutch, who were allowed to continue to trade with Japan from the confines of a small man-made island in Nagasaki, Deshima. Macau's most profitable trade route, that between Japan and China, had been severed. The crisis was compounded two years later by the loss of Malacca to the Dutch in 1641, damaging the link with Goa.

The news that the Portuguese House of Braganza had regained control of the Crown from the Spanish Habsburgs took two years to reach Macau, arriving in 1642. A ten-week celebration ensued, and despite its new-found poverty, Macau sent gifts to the new King João IV along with expressions of loyalty. In return, the King rewarded Macau with the addition of the words "There is none more Loyal" to its existing title. Macau was now "City of the Name of God, Macau, There is none more loyal". ("Cidade do Nome de Deus, Macau, Nao Ha Outra Mais Leal" []).[28]

In 1685, the privileged position of the Portuguese in trade with China ended, following a decision by the Kangxi Emperor of China to allow trade with all foreign countries. Over the next century, Britain, the Dutch Republic, France, Denmark, Sweden, the United States and Russia moved in, establishing factories and offices in Guangzhou and Macau. British trading dominance in the 1790s was unsuccessfully challenged by a combined French and Spanish naval squadron at the Macau Incident of 27 January 1799.

Until 20 April 1844 Macau was under the jurisdiction of Portugal's Indian colonies, the so-called "Estado português da India" (Portuguese State of India), but after this date, it, along with East Timor, was accorded recognition by Lisbon (but not by Beijing) as an overseas province of Portugal.

The Treaty of Peace, Amity, and Commerce between China and the United States was signed in a temple in Macau on 3 July 1844. The temple was used by a Chinese judicial administrator, who also oversaw matters concerning foreigners, and was located in the village of Mong Há. The Templo de Kun Iam was the site where, on 3 July 1844, the treaty of Wangxia (named after the village of Mong Ha where the temple was located) was signed by representatives of the United States and China. This marked the official beginning of Sino-US relations.

1844–1938: The Hong Kong effect

[edit]

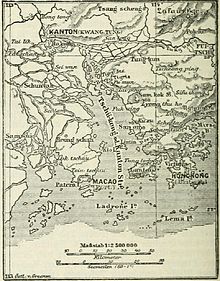

After China ceded Hong Kong to the British in 1842, Macau's position as a major regional trading centre declined further still because larger ships were drawn to the deep-water port of Victoria Harbour.[29] In 1846, Portugal dispatched João Maria Ferreira do Amaral to serve as governor of Macau.[30]: 81 He unilaterally declared Macau a Portuguese colony, stopped annual rent payments to China, occupied the nearby Island of Taipa (which had never been Portuguese territory), and imposed a new series of taxes on Macau residents.[30]: 81 In 1846, there was a revolt of the boatmen that was put down.

While supervising road construction, Amaral ordered the destruction of Chinese tombs in the area. In the Baishaling incident, Amaral was ambushed and killed by a group of Chinese villagers he encountered while riding outside the city gates.[30]: 81 The Portuguese responded with a surprise attack on a nearby Chinese fort, forcing the Chinese to retreat.[30]: 81 This was a milestone in the Portugal's assertion of sovereignty over Macau.[30]: 81–82 Portugal gained control of the island of Wanzai (Lapa by the Portuguese and now as Wanzaizhen), to the northwest of Macau and which now is under the jurisdiction of Zhuhai (Xiangzhou District), in 1849 but relinquished it in 1887. Control over Taipa and Coloane, two islands south of Macau, was obtained between 1851 and 1864. Macau and East Timor were again combined as an overseas province of Portugal under control of Goa in 1883. The Protocol Respecting the Relations Between the Two Countries (signed in Lisbon 26 March 1887) and the Beijing Treaty (signed in Beijing on 1 December 1887) confirmed "perpetual occupation and government" of Macau by Portugal (with Portugal's promise "never to alienate Macau and dependencies without agreement with China" in the treaty). Taipa and Coloane were also ceded to Portugal, but the border with the mainland was not delimited. Ilha Verde (Chinese: 青洲; pinyin: Qīngzhōu; Jyutping: Ceng1 Zau1 or Cing1 Zau1) was incorporated into Macau's territory in 1890, and, once a kilometre offshore, by 1923 it had been absorbed into peninsula Macau through land reclamation.[citation needed]

In 1871, the Hospital Kiang Wu was founded as a traditional Chinese medical hospital. It was in 1892 that doctor Sun Yat-sen brought Western medicine services to the hospital.[31]

In the 1930s, Macau's traditional income streams related to illegal opium sales dried up, as the Royal Navy's Eastern Fleet suppressed piracy and smuggling in support of Hong Kong's growing commercial status. Traditional local industries of fishing, firecrackers and incense, as well as tea and tobacco processing, were all small scale, while Macau government income from 'Fan-Tan' gambling was only around US$5000 (about US$100,000 in modern money) per day. So the financially pressed Portuguese government urged the colony's administrators to develop greater economic self-sufficiency. One channel that bore fruit was as a transit point for the new trans-Pacific passenger and postal flights, for competing airlines from the US and Japan – which was at the time engaged in conflict with China. In 1935, Pan-Am secured sea-landing rights in Macau and immediately set about building related communications infrastructure in the enclave, allowing a service from San Francisco to begin in November that year.[32]

Intertwined with this economic progress was an alleged and much discussed offer (never officially confirmed) in 1935 by Japan to buy Macau from Portugal, for US$100 million. Concerns were raised by the British, and others. In May, the Portuguese government twice denied that it would accept any such offer, and the matter was closed.[32]

1848–1870s: Slave trade

[edit]From 1848 to about the early 1870s, Macau was the infamous transit port of a trade of coolies (or slave labourers) from southern China. Between 1851 and 1874 approximately 215,000 Chinese were shipped from Macau overseas, primarily to Cuba and Peru, with some being shipped to Guiana, Suriname, and Costa Rica.[30]: 82 Coolies were obtained via variety of sources, including some who were entrapped by brokers in Macau through loans for gambling, and others who were kidnapped or coerced.[30]: 82

1938–1949: World War II

[edit]Macau became a refugee centre during World War II, causing its population to climb from about 200,000 to about 700,000 people within a few years.[33] Refugee operations were organised through the Santa Casa da Misericordia.[34]

Unlike in the case of Portuguese Timor, which was occupied by the Japanese in 1942 along with Dutch Timor, the Japanese respected Portuguese neutrality in Macau, but only up to a point.[33] As such, Macau enjoyed a brief period of economic prosperity, being the only neutral port in South China, after the Japanese had occupied Guangzhou (Canton) and Hong Kong.[35] In August 1943, Japanese troops seized the British steamer Sian in Macau and killed about 20 guards. The next month, they demanded the installation of Japanese "advisors" under the alternative of military occupation. The result was that a virtual Japanese protectorate was created over Macau.

On June 26, 1942, a Hawker Osprey III (6) of Aeronáutica Naval crashed into a residential area in Macau, killing both occupants as well as one person on the ground.[36] This is the only fatal aircraft accident to have taken place in Macau.

Having been neutral during World War II, Portugal was not a signatory to the 1944 Bretton Woods Agreement.[30]: 87 Combined with its geographical location, this meant that Macau was an ideal hub for the illicit gold trade among those seeking to avoid the price controls on gold imposed by the Bretton Woods Agreement.[30]: 87 Following the 1971 U.S. abandonment of the Bretton Woods System through the Nixon shock, Macau's significance to the gold trade declined, and its illicit gold trade ended in 1974.[30]: 88

When it was discovered that neutral Macau was planning to sell aviation fuel to Japan, aircraft from the USS Enterprise bombed and strafed the hangar of the Naval Aviation Centre on 16 January 1945 to destroy the fuel. American air raids on targets in Macau were also made on 25 February and 11 June 1945. Following Portuguese government protest in 1950, the United States paid US$20,255,952 compensation to the government of Portugal.[37]

1949–1999: Macau and the People's Republic of China

[edit]When the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) came to power in 1949, the CCP declared the Protocol of Lisbon to be invalid as an "unequal treaty" imposed by foreigners on China. However, Beijing was not ready to settle the treaty question, leaving the maintenance of "the status quo" until a more appropriate time. Beijing took a similar position on treaties relating to the Hong Kong territories of the United Kingdom.

Following World War II, the United Nations expected its member states to relinquish any colonies. Portuguese Prime Minister Antonio Salazar sought to resist UN pressure to relinquish Macau.[30]: 84 In 1951, the Salazar regime eliminated the phrase "colonial empire" from its constitution and sought to re-characterize Macau not as a colony but as an overseas province of Portugal, which it viewed as part of a plural-continental but nonetheless unified and indivisible Portuguese state.[30]: 84

During the Korean War, Macau was a major site for the smuggling of arms into China to avoid United Nations mandates.[30]: 82 After the armistice, Macau became a semi-official gateway for North Korea's diplomatic and financial interests, with a Macau trading company serving as North Korea's de facto consulate in Macau.[30]: 82

During the 1950s and 1960s Macau's border crossing to China Portas do Cerco was also referred to as Far Eastern Checkpoint Charlie with a major border incident happening in 1952 with Portuguese African Troops exchanging fire with Chinese Communist border guards.[38] According to reports, the exchange lasted for one-and-three-quarter hours, leaving one dead and several dozens injured on the Macau side and more than 100 casualties claimed on the Communist Chinese side.[39]

In 1954, the Macau Grand Prix was established, first as a treasure hunt throughout the city, and in later years as a formal car racing event.[40]

In 1962, the gambling industry of Macau saw a major breakthrough when the government granted the Sociedade de Turismo e Diversões de Macau (STDM), a syndicate jointly formed by Hong Kong and Macau businessmen, the monopoly rights to all forms of gambling. The STDM introduced western-style games and modernised the marine transport between Macau and Hong Kong, bringing millions of gamblers from Hong Kong every year.[41]

Riots broke out in 1966 during the Cultural Revolution, when local Chinese and the Macau authority clashed, the most serious one being the 12-3 incident.[30]: 84 This was prompted by government delays in approving a new wing for a Communist Party elementary school in Taipa.[30]: 84 The school board illegally commenced construction. the colonial government sent police to stop the workers, and several people were injured in the conflict.[30]: 84 On December 3, 1966, two days of rioting occurred in which hundreds were injured and six[30]: 84 to eight people were killed, leading also to a total climbdown by the Portuguese government.[42] The event set in motion de facto abdication of Portuguese control over Macau, putting it on the path to eventual decolonization.[30]: 84–85

On 29 January 1967, the Portuguese governor, José Manuel de Sousa e Faro Nobre de Carvalho, with the endorsement of Portuguese prime minister Salazar, signed a statement of apology at the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, under a portrait of Mao Zedong, with Ho Yin, the chamber's president, presiding.[43][44]

Two agreements were signed, one with Macau's Chinese community, and the other with mainland China. The latter committed the government to compensate local Chinese community leaders with as much as 2 million Macau patacas and to prohibit all Kuomintang activities in Macau.[30]: 85 This move ended the conflict, and relations between the government and the leftist organisations remained largely peaceful.[45]

This success in Macau encouraged leftists in Hong Kong to "do the same", leading to riots by leftists in Hong Kong in 1967.

After the 1974 Carnation Revolution overthrew the dictatorship of Marcelo Caetano, Portugal began a formal process of decolonization.[30]: 85 Over the next several years, it made two offers to return the Macau and China rejected both.[30]: 85 In 1979, Portugal and China established formal diplomatic relations and reached a secret agreement to characterize Macau as a Chinese territory under Portuguese administration.[30]: 85

In 1994, the Bridge of Friendship was completed, the second bridge connecting Macau and Taipa.[46]

In November 1995, the Macau International Airport was inaugurated.[46] Before then the territory only had 2 temporary airports for small aeroplanes, in addition to several permanent heliports.

In 1997, the Macau Stadium was completed in Taipa.[46]

Over a three year period in the late 1990s, as wave of gang violence referred to as the casino wars occurred in Macau.[30]: 11 The casino wars were largely attributable to rival Triad groups who sought to gain control of Macau's illicit industries before Portugal transferred the territory back to China.[30]: 11 The Portuguese authorities of Macau mostly failed to address the violence, which resulted in 122 deaths, or to catch those responsible.[30]: 11

1999: Handover to the People's Republic of China

[edit]Portugal and the People's Republic of China established diplomatic relations on 8 February 1979, and Beijing acknowledged Macau as "Chinese territory under Portuguese administration." A year later, Gen. Melo Egidio became the first governor of Macau to pay an official visit to Beijing.

The visit underscored both parties' interest in finding a mutually agreeable solution to Macau's status. A joint communique signed 20 May 1986 called for negotiations on the Macau question, and four rounds of talks followed between 30 June 1986 and 26 March 1987. The Joint Declaration on the Question of Macau was signed in Beijing on 13 April 1987, setting the stage for the return of Macau to full Chinese sovereignty as a Special Administrative Region on 20 December 1999.

After four rounds of talks, "the Joint Declaration of the Government of the People's Republic of China and the Government of the Republic of Portugal on the Question of Macau" was officially signed in April 1987. The two sides exchanged instruments of ratification on 15 January 1988 and the Joint Declaration entered into force. During the transitional period, between the date of the entry into force of the Joint Declaration and 19 December 1999, the Portuguese government was responsible for the administration of Macau.

The Basic Law of the Macau Special Administrative Region of the People's Republic of China, was adopted by the National People's Congress (NPC) on 31 March 1993 as the constitutional law for Macau, taking effect on 20 December 1999.

The PRC has promised that, under its "one country, two systems" formula, China's socialist economic system will not be practised in Macau and that Macau will enjoy a high degree of autonomy in all matters except foreign and defence affairs until, at least, 2049, fifty years after the handover.

Upon the handover of Macau European colonisation of Asia ended.

Recent history of Macau (1999–present)

[edit]1999–2007: The rise of Macau as the Las Vegas of Asia

[edit]In 2002, the Macau government ended the gambling monopoly system and 3 (later 6) casino operating concessions (and subconcessions) were granted to Sociedade de Jogos de Macau (SJM, an 80% owned subsidiary of STDM), Wynn Resorts, Las Vegas Sands, Galaxy Entertainment Group, the partnership of MGM Mirage and Pansy Ho Chiu-king, and the partnership of Melco and PBL, thus marking the begin of the rise of Macau as the new gambling hub in Asia.

As one of the measures to develop the gambling industry, the Cotai reclamation was completed after the handover to China, with construction of the hotel and casino industry starting in 2004. In 2007, the first of many resorts opened, The Venetian Macao. Many other resorts followed, both in Cotai and on Macau island, providing for a major tax income stream to Macau government and a drop in overall unemployment over the years down to a mere 2% in 2013.[47]

In 2004, the Sai Van Bridge was completed, the third bridge between Macau island and Taipa island.[46]

In 2005, the Macau East Asian Games Dome, the principal venue for the 4th East Asian Games, was inaugurated.[46]

Also in 2005, the Macau government started a wave of social housing construction (lasting until 2013 at least), constructing over 8000 apartment units in the process.[48]

2007–2008: The Financial Crisis hits Macau

[edit]Similar to other economies in the world, the financial crisis of 2007–08 hit Macau, leading to a stall in construction of major construction works (Sands Cotai Central[49]) and a spike in unemployment.[50]

2008–2013: Expansion into Hengqin and further Casino boom

[edit]With residential and development space being sparse, Macau government officially announced on 27 June 2009 that the University of Macau will build its new campus on Hengqin island, in a stretch directly facing the Cotai area, south of the current border post. Along with this development, several other residential and business development projects on Hengqin are in the planning.

In 2011 to 2013, further major construction on several planned mega-resorts in Cotai commenced.[51]

2014–present: Slowing down of the gambling industry and diversification of economy

[edit]2014 marked the first time that the gambling revenues in Macau declined on a year-to-year basis. Starting in June 2014, gambling revenues declined for the second half of the year on a month-to-month basis (compared with 2013) causing the Macau Daily Times to announce that the "Decade of gambling expansion end[ed]".[52] Some reasons for the slowdown are China's anti-corruption drive reaching Macau, China's economy slowing down and changes of Mainland Chinese tourists' preference of visiting other countries as a travel destination.[53][54]

This led the Macau government to attempt to reconstruct the economy, to depend less on gambling revenues and focus on building world-class non-gambling tourism and leisure centres, as well as developing itself as a platform for economic and trade cooperation between China and Portuguese-speaking countries.[55]

In 2015, the borders of Macau were redrawn by the state council, shifting the land border north to the Canal dos Patos and expanding the maritime border significantly. The changes increased the size of Macau's maritime territory by 85 square kilometres.[56]

Typhoon Hato hit Southern China in August 2017, causing widespread damage to Macau, never before experienced – major flooding and property damages, with citywide power and water outages lasting for at least 24 hours after the passage of the storm. Overall, 10 deaths and at least 200 injuries were reported. This caused widespread anger against the Macau government, accused of being unprepared for the typhoon as well as the delay of raising the No. 10 tropical cyclone signal; this caused the head of the Macao Meteorological and Geophysical Bureau to resign.[57] At the request of the Macau government, the Chinese People's Liberation Army Macau Garrison (for the first time in Macau's history) deployed around 1,000 troops to assist in disaster relief and cleaning up.[58]

On 12 December 2019, Macau officially opened its first rail transit system: the Macau Light Rapid Transit.[59]

Overall, Macau was among the safest places in the world during the COVID-19 pandemic, with relatively few infections and a large array of medical, social, and financial response measures.[30]: 298 Macau's casino-reliant economy was greatly slowed by the pandemic.[30]: 298

See also

[edit]- Anders Ljungstedt

- Culture of Macau

- Gambling in Macau

- Lisbon-Macau Raid

- Military of Macau under Portuguese rule

- Jorge Álvares

- Names of Macau

- Religion in Macau

- History of Hong Kong

References

[edit]- ^ Robert Nield, "Treaty Ports and Other Foreign Stations in China", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, Hong Kong Branch, Vol. 50, (2010), p. 127.

- ^ "文章内容". www.macaudata.mo. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- ^ a b "Macau history in Macau Encyclopedia" (in Chinese). Macau Foundation. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007. Retrieved 12 January 2008.

- ^ a b "15: History" (PDF). Government Information Bureau of the MSAR.

Historical records show that Macao has been Chinese territory since long ago. When Qinshihuang (the first emperor of the Qin dynasty) unified China in 221 BC, Macao came under the jurisdiction of Panyu County, Nanhai Prefecture. Administratively, it was part of Dongguan Prefecture in the Jin dynasty (AD 266–420), then Nanhai County during the Sui dynasty (AD 581–618), and Dongguan County in the Tang dynasty (AD 618–907). In 1152, during the Southern Song dynasty, the Guangdong administration joined the coastal areas of Nanhai, Panyu, Xinhui and Dongguan Counties to establish Xiangshan County, thus bringing Macao under its jurisdiction.

- ^ a b c Minahan, James B. (2014). Ethnic Groups of North, East, and Central Asia: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-61069-018-8.

- ^ Hao, Zhidong (2011). Macau History and Society. Hong Kong University Press. p. 15. ISBN 978-988-8028-54-2.

- ^ a b c Macao Electoral, Political Parties Laws and Regulations Handbook – Strategic Information, Regulations, Procedures. IBP. Inc. 2015. p. 32. ISBN 978-1-5145-1727-7.

- ^ davide. "Macau's Early History". Retrieved 25 March 2021.

- ^ a b Background Notes, Macau. Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs, U.S. Department of State. 1994. p. 2. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- ^ Ride, Lindsay; et al. (1999). The Voices of Macao Stones: The Nanjing Massacre Witnessed by American and British Nationals. Hong Kong University Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-962-209-487-1.

- ^ p. 343-344, Denis Crispin Twitchett, John King Fairbank, The Cambridge history of China, Volume 2; Volume 8, Cambridge University Press, 1978, ISBN 0-521-24333-5

- ^ Ptak, Roderich (1992), "Early Sino-Portuguese relations up to the Foundation of Macao", Mare Liberum, Revista de História dos Mares (4), Lisbon, archived from the original on 3 March 2016

- ^ Fung, Bong Yin (1999). Macau: a General Introduction (in Chinese). Hong Kong: Joint Publishing (H.K.) Co. Ltd. ISBN 962-04-1642-2.

- ^ Joseph Timothy Haydn (1885). Dictionary of dates, and universal reference. [With] (18 ed.). p. 522. Archived from the original on 5 June 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

MACAO (in Quang-tong, S. China) was given to the Portuguese as a commercial station in 1586 (in return for their assistance against pirates), subject to an annual tribute, which was remitted in 1863. Here Camoens composed part of the " Lusiad."

(Oxford University) - ^ Indiana UniversityCharles Ralph Boxer (1948). Fidalgos in the Far East, 1550–1770: fact and fancy in the history of Macao. M. Nijhoff. p. 224. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

Some of these wants and strays found themselves in queer company and places in the course of their enforced sojourn in the Portuguese colonial empire. The Ming Shih's complain that the Portuguese kidnapped not only coolie or Tanka children but even those of educated persons, to their piratical lairs at Lintin and Castle Peak, is borne out by the fate of Barros' Chinese slave already

- ^ Jonathan Chaves (1993). Singing of the source: nature and god in the poetry of the Chinese painter Wu Li (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-8248-1485-1. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

Wu Li, like Bocarro, noted the presence in Macao both of black slaves and of non-Han Chinese such as the Tanka boat people, and in the third poem of his sequence he combines references to these two groups: Yellow sand, whitewashed houses: here the black men live; willows at the gates like sedge, still not sparse in autumn.

- ^ Jonathan Chaves (1993). Singing of the source: nature and god in the poetry of the Chinese painter Wu Li (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 54. ISBN 0-8248-1485-1. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

Midnight's when the Tanka come and make their harbor here; fasting kitchens for noonday meals have plenty of fresh fish ... The second half of the poem unfolds a scene of Tanka boat people bringing in fish to supply the needs of fasting Christians.

- ^ Jonathan Chaves (1993). Singing of the source: nature and god in the poetry of the Chinese painter Wu Li (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 141. ISBN 0-8248-1485-1. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

3 Yellow sand, whitewashed houses: here the black men live; willows at the gates like sedge, still not sparse in autumn. Midnight's when the Tanka come and make their harbor here; fasting kitchens for noonday meals have plenty of fresh fish.

- ^ Jonathan Chaves (1993). Singing of the source: nature and god in the poetry of the Chinese painter Wu Li (illustrated ed.). University of Hawaii Press. p. 53. ISBN 0-8248-1485-1. Archived from the original on 7 July 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2012.

The residents Wu Li strives to reassure (in the third line of this poem) consisted – at least in 1635 when Antonio Bocarro, Chronicler-in-Chief of the State of India, wrote his detailed account of Macao (without actually having visited there) — of some 850 Portuguese families with "on the average about six slaves capable of bearing arms, amongst whom the majority and the best are negroes and such like," as well as a like number of "native families, including Chinese Christians ... who form the majority [of the non-Portuguese residents] and other nations, all Christians." 146 (Bocarro may have been mistaken in declaring that all the Chinese in Macao were Christians.)

- ^ Porter, Jonathan. Macau, the Imaginary City: Culture and Society, 1557 to the Present. Westview Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0-8133-3749-4

- ^ "Macau – a unique city". Macau Tourist Guide. Archived from the original on 20 May 2007. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ "The British Presence in Macau, 1635–1793".

- ^ C. R. Boxer, Fidalgos in the Far East, 1550–1770. Martinus Nijhoff (The Hague), 1948. p. 4

- ^ Indrani Chatterjee, Richard Maxwell Eaton (2006). Indrani Chatterjee, Richard Maxwell Eaton (ed.). Slavery and South Asian history (illustrated ed.). Indiana University Press. p. 238. ISBN 0-253-21873-X. Archived from the original on 29 May 2013. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

Portuguese,"he concluded;"The Portuguese beat us off from Macao with their slaves."10 The same year as the Dutch ... an English witness recorded that the Portuguese defence was conducted primarily by their African slaves, who threw

- ^ Boxer, p. 99

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "The Catholic entry in Macau Encyclopedia" (in Chinese). Macau Foundation. Archived from the original on 24 December 2007. Retrieved 6 January 2008.

- ^ "Step onto Senado Square and into the past: Walking tours bring Macau's Chinese, Portuguese history in focus". South China Morning Post.

- ^ Mirza, Rocky M. (2019). Understanding the global shift, the popularity of Donald Trump, Brexit and discontent in the West : rise of the emerging economies: 1980 to 2018. [Bloomington, IN]. ISBN 978-1-4907-9327-6. OCLC 1117312614.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab Simpson, Tim (2023). Betting on Macau: Casino Capitalism and China's Consumer Revolution. Globalization and Community series. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-1-5179-0031-1.

- ^ As published on IACM Macau government publication "Footprints of Painter Gao Jianhu"

- ^ a b Did Japan really offer Portugal US$100 million for Macau in 1935?, SCMP by Paul French, 8 February 2020

- ^ a b Paulo Barbosa (2 May 2012). "Q&A: "Macau was safe haven" during WWII". Archived from the original on 7 January 2014. Retrieved 7 January 2014.

- ^ Gunn, Geoffrey (2016). Wartime Macau: Under the Japanese Shadow. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press. p. 105. ISBN 978-988-8390-51-9.

- ^ Ptak, Roderich (2017). "Review of Wartime Macau: Under the Japanese Shadow". Journal of Asian History. 51 (2): 328–333. doi:10.13173/jasiahist.51.2.0328. ISSN 0021-910X.

- ^ "Accident Hawker Ospray III 6". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ p.116 Garrett, Richard J. The Defences of Macau: Forts, Ships and Weapons Over 450 Years Hong Kong University Press, 1 February 2010

- ^ Wordie, Jason (2013). "1. Portas do Cerco". Macao – People and Places, Past and Present. Hong Kong: Angsana Limited. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-988-12696-0-7.

- ^ "Macao Portuguese Fire Over Border". The West Australian. Perth: Perth, W. A. : A. Davidson, for the West Australian, 1879. 31 July 1952. Retrieved 2 December 2013.

- ^ Grand Prix Macau. "THE 50s: All THAT BEGINS". Archived from the original on 26 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ Chan, S. S. (2000). The Macau Economy. Macau: Publications Centre, University of Macau. ISBN 99937-26-03-6.

- ^ Portugal, China and the Macau Negotiations, 1986–1999, Carmen Amado Mendes, Hong Kong University Press, 2013, page 34

- ^ Naked Tropics: Essays on Empire and Other Rogues Archived 21 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Kenneth Maxwell, Psychology Press, 2003, page 279

- ^ "A guerra e as respostas militar e política 5.Macau: Fim da ocupação perpétua (War and Military and Political Responses 5.Macau: Ending Perpetual Occupation)". RTP.pt. RTP. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ "Macau (09/08)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 3 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d e As displayed on the official timeline of Macau at the Museum of History in Taipa

- ^ Max-Leonhard von Schaper (3 November 2013). "Macau: Unemployment Rates during the past 8 years". Archived from the original on 26 November 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ Insituto de Habitacao. "Social Housing". Archived from the original on 31 December 2013. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

- ^ Hsin Chong Construction Group Ltd. (12 April 2012). "Sands Cotai Central Opens in Macau". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ^ Max-Leonhard von Schaper (7 November 2013). "Macau: Unemployment in Total Figures". Archived from the original on 27 November 2013. Retrieved 7 December 2013.

- ^ Kelvin Chan, AP (Macau Daily Times) (2 May 2012). "Wynn Macau gets OK for Cotai casino development". Archived from the original on 29 December 2013. Retrieved 29 December 2013.

- ^ Macau Daily Times (5 January 2015). "A DECADE OF GAMBLING EXPANSION ENDS". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 January 2015.

- ^ Feng, Xiaoyun (17 October 2015). "Macau economy undergoing great reconstruction". Ejinsight. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ Ge, Celine (11 October 2016). "Chinese tourists skipped Hong Kong, Taiwan and headed farther afield during Golden Week". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 18 October 2016. Retrieved 20 October 2016.

- ^ Cardoso, Pedro (16 October 2017). "Macau bridges the gap between Chinese and Portuguese markets". World Finance. Archived from the original on 16 October 2017. Retrieved 16 October 2017.

- ^ "Macau to extend land and sea administrative area". South China Morning Post. 17 December 2015. Retrieved 10 November 2019.

- ^ Carvalho, Raquel; Mok, Danny. "Macau observatory chief resigns as government slammed for response to deadly typhoon". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 3 September 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ Yeung, Raymond; Carvelho, Raquel. "Up to 10 people feared trapped in flooded underground car parks after Typhoon Hato devastates Macau". South China Morning Post. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Macau's long-delayed light rail or tram service begins carrying passengers". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

Further reading

[edit]- Collis, Maurice. "Macao: The City of the Name of God." History Today (Apr 1951) 1#4 pp 42–49 online.

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. Encountering Macau, A Portuguese City-State on the Periphery of China, 1557–1999 (Boulder: Westview Press, 1996) ISBN 0-8133-8970-4 In Portuguese (1998) Ao Encontro de Macau: Uma cidade-estado portuguesa a periferia da China, 1557–1999 (Macau: Fundação Macau]. ISBN 972-658-074-9 In Chinese (2009) 澳门史:1557~1999 (中央编译出版社).

- Gunn, Geoffrey C. (ed.) Wartime Macau: Under the Japanese Shadow (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2016). ISBN 978-988-8390-51-9

- Porter, Jonathan. "'The Past Is Present': The Construction of Macau's Historical Legacy," History and Memory Volume 21, Number 1, Spring/Summer 2009 pp. 63–100

- Porter, Jonathan. Macau: The Imaginary City, Culture and Society, 1557 to the Present (Boulder: Westview Press, 1996)

- Schellinger and Salkin, ed. (1996). "Macau". International Dictionary of Historic Places: Asia and Oceania. UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-884964-04-6.

- Souza, George Bryan. The Survival of Empire: Portuguese Trade and Society in China and the South China Sea, 1630–1754 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986)

- Coates, Austin: A Macao Narrative

- Shipp, Steve: Macau, China: A Political History of the Portuguese Colony's Transition to Chinese Rule

- Clayton, Cathryn (2012). "The hapless imperialist? Portuguese rule in 1960s Macau". In Goodman, Bryna; Goodman, David (eds.). Twentieth Century Colonialism and China (1 ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203125458. ISBN 978-0-203-12545-8.