Luigi Domenico Gismondi

Luigi Domenico Gismondi | |

|---|---|

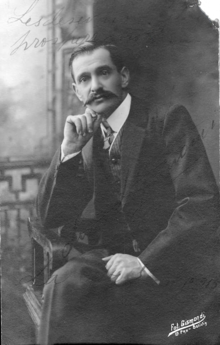

Self-portrait, Gismondi Studio, La Paz | |

| Born | 9 August 1872 |

| Died | 1946 (aged 73–74) Arequipa, Peru |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Known for | Photography |

| Spouse |

Inés Morán (m. 1901) |

| Children | Fourteen |

| Parent(s) | Pietro Gismondi Maria Modena |

Luigi Domenico Gismondi (9 August 1872 – 1946) was an Italian prolific photographer, photographic-supplies vendor, and postcard publisher active in Bolivia and the areas of southern Peru and northern Chile. Gismondi was a pioneer in photography in Bolivia, documenting various cultural aspects and numerous personalities while at the same time creating a comprehensive exhibit of regional architecture and geography. The Gismondi archive is notable for being one of the first to include a wide array of photographs of indigenous people from different regions.

Early life

[edit]Luigi Domenico Gismondi was born on 9 August 1872 to Pietro Gismondi and Maria Modena. Originally from Sanremo, Italy, in the 1890s, he emigrated with his parents and three siblings to Peru, fleeing economic destitution in his home country. Upon landing in Mollendo, Gismondi and his elder brothers, Giacinto and Stefano, both photographers, established their business, advertised as Gismondi Hnos. or Gismondi y Cía. The siblings traveled across Peru, including Lima, Cusco, and Arequipa, with services ranging from oil, watercolor, and pastel portraits, to historical and mythological paintings, to décor styled after the Italian Renaissance.[1][2] The Sagrado Corazón temple, known as the Sistine Chapel of Colán, was painted by Gismondi's elder brothers.[3]

Around this time, Gismondi was active as a photographer, traveling the areas of southern Peru, northern Chile, and western Bolivia. In 1901, he married the Peruvian Inés Morán in Arequipa, with whom he had fourteen children, only seven of whom survived to adulthood. That year, Gismondi became active in Bolivia, settling in the city of La Paz in 1904, where he established the Gismondi Photo Studio, which became the center of his professional activity for the duration of his career.[2][4]

Photography career

[edit]

Though Gismondi's work primarily focused on the city and department of La Paz, his photographic career also took him to nearly the entire territory of the country, including cross-border projects in central and southern Peru and northern Chile, as well as some in Argentina and Paraguay. In Bolivia, Gismondi's photographic record of the country was extensive; it included one of the first systematic records of the La Paz Department, documenting aspects of the urban city as well as the surrounding Altiplano and tropical Yungas regions. He was the first to create a documented record of the country's colonial and republican architecture, which has been compared to similar works by Mexican photographer Guillermo Kahlo; and was one of Bolivia's first industrial photographers, documenting several mining and railroad sites, mainly in the Potosí Department.[5]

A majority of the work carried out at Gismondi's La Paz studio consisted of official photographs and formal portraits of individuals.[5] During his time in La Paz, Gismondi met President José Manuel Pando, who appointed him as the official photographer of the presidency.[2] Gismondi maintained this position for the rest of his life, photographing every president of Bolivia from Pando (1899–1904) to Gualberto Villarroel (1943–1946).[6] He also took official portraits of prominent diplomats, government ministers, and members of the ecclesiastical hierarchy of the Catholic Church, such as the archbishops.[7]

Notably, Gismondi took a large quantity of photographs of indigenous peoples, being one of the few photographers interested in portraying them at the time.[8] His representation of groups like the cholas, highlighting their extravagant outfits and representing them in a dignified manner, came at a time when such figures represented a distinct lower-class in Bolivian society. Of particular note among these is Men Pulling a Rope, which features three indigenous men performing the photograph's namesake action, conveying the concept of a strong indigenous race. These photographs became a popular item on postcards and helped advance the indigenist movement in Bolivia.[9][10]

Apart from the cultural relevance of his works, Gismondi also contributed heavily to the practice of photography in South America, bringing with him Italian technology and equipment like curtains, carpets, cameras, chemical material for developing, glass plates, and acetate, among others.[6] Upon his death in 1946, the Gismondi Studio continued its official photographic work through his son Luis Adolfo, his granddaughter Ruth, and his great-granddaughter Geraldine.[8]

Gallery

[edit]-

Tiahuanaco. c. 1907. Diran Sirinian Collection, Buenos Aires

-

Men Pulling a Rope. c. 1925. Gismondi Studio Archive, La Paz

-

Children dressed for the La Paz Carnival at the Gismondi studio, c. 1941

-

Aymara Indian, Bolivia. Quechua Indian, Peru. c. 1917. Gismondi Studio Archive, La Paz

-

Chola Paceña, Grand Dame. c. 1925. Gismondi Studio Archive, La Paz

-

Charote Chiefs. c. 1902–1909. Gismondi Studio Archive, La Paz

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Buck 1999, p. 21

- ^ a b c Bajo, Ricardo (13 January 2021). "Los Gismondi: Un legado fotográfico rico y vivo". La Razón (in Spanish). La Paz. Archived from the original on 14 January 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Garay Albújar, Andrés (26 July 2011). "La Capilla Sixtina de Colán". udep.edu.pe (in Spanish). Piura: University of Piura. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ Querejazu Leyton 2016, p. 75

- ^ a b Querejazu Leyton 2016, p. 77

- ^ a b "Hechos históricos perduran con fotografías de Gismondi". El Diario (in Spanish). La Paz. 10 August 2019. Archived from the original on 10 June 2022. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

- ^ Querejazu Leyton 2016, p. 79

- ^ a b "La Paz celebra el centenario del legado fotográfico de Luigi Gismondi". Opinión (in Spanish). Cochabamba. 9 August 2019. Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 20 April 2021.

- ^ Querejazu Leyton 2016, p. 80

- ^ Baldivieso, Gina (10 August 2019). Written at La Paz. "La Paz celebrates 100-year photo legacy of Luigi Gismondi". EFE. Madrid. Archived from the original on 21 April 2021. Retrieved 19 April 2021.

Bibliography

[edit]- Buck, Daniel (1999). Pioneer Photography in Bolivia: Directory of Daguerreotypists and Photographers, 1840s–1930s. Washington, D.C. p. 21 – via Issuu.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Querejazu Leyton, Pedro (2016). "Miradas desde la Otredad: La Construcción de la Imagen de Bolivia en la Obra Fotográfica de Luigi Doménico Gismondi". Diálogo Andino (in Spanish) (50): 75–84. doi:10.4067/S0719-26812016000200006. ISSN 0719-2681.

Further reading

[edit]- Aliaga G., Jorge (2007). Estudio Gismondi: Cien Años, Cuatro Generaciones (in Spanish). La Paz: Museo Nacional de Arte. OCLC 255289303.

- Querejazu Leyton, Pedro (2009). Luigi Domenico Gismondi: Un Fotógrafo Italiano en La Paz (in Spanish). La Paz. ISBN 978-99954-0-753-7. OCLC 659732039.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)