Louise Alexander (dancer)

Louise Alexander (June 29/30, 1888 – October 29, 1958), born Jennie Louise Spalding, was an American theatrical and social exhibition dancer between 1905 and 1916. She began as a chorus girl, soon became a pantomime dancer (Apache dance, temptress dance), then an exhibition social dancer in restaurants and on the vaudeville stage.

Early life

[edit]Jennie Louise Spalding was born in Hartford, Kentucky on June 29 or 30, 1888.[1] Her mother was Nanna/Nannie/Nancy Alexander Spalding and her father was William L. Spalding.[2] Until the age of 18 she lived in Kentucky, primarily in either Louisville, where her father worked, or Owensboro, where her grandparents lived.[3] In late 1905 she moved to New York City and adopted the stage name Louise Alexander.

Career

[edit]Chorus girl

[edit]Between 1905 and 1908 Louise Alexander worked as a chorus girl in musicals on Broadway and on tour. Her parts frequently included speaking roles. She appeared in The Earl and the Girl,[4] The Social Whirl,[5] Ziegfeld Follies of 1907,[6] and Follies of 1908.[7]

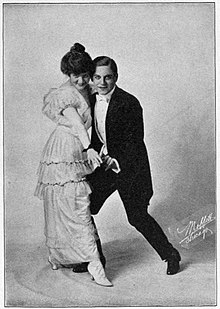

Apache dancer

[edit]

The French Apache dance came into theatrical prominence in July 1908 when it was danced by Mistinguett and Max Dearly in Revue de Moulin, presented at the Moulin Rouge in Paris.[8][9] In October 1908 the dance became a London hit when danced as "Danse des Apaches" by Beatrice Collier and Fred Farren as part of the Music Hall ballet A Day in Paris.[10] In America the first major Apache dance presentation was titled "The Underworld Dance", performed by Louise Alexander and Joseph C. Smith in the hit musical comedy-drama The Queen of the Moulin Rouge,[11] which opened in New York on December 7, 1908.

Smith later wrote, "When I first tried the Apache dance with Louise Alexander her hair accidentally fell down, which greatly added to the effect of the thing...So I had big bone hairpins made, with weights to them. These she wore, and they would drop out and her hair would fall down during the dance."[12]

A New York reviewer observed that the dance was "rather rough on a young woman who was maltreated by a sallow-faced brute until her lovely hair was hanging down her back."[13]

Another reviewer wrote that the dance, "...is the most sensational thing in its line that New York has seen in many a day. A street tough throws his 'bundle' through the dance. How she endures the strain is a marvel."[14]

Discussing the brutality of the dance, Louise Alexander reportedly told the New York Times,

I do not even feel the hurts of his beating and choking me, not even when, in the final battle for supremacy between the love of the girl and the brutal instincts of the thug, he throws me actually and fearfully to the floor. It is all fine. Exhilarating, but such a terrific mental, physical, and nervous strain that I am absolutely exhausted after each performance. ...My partner in the dance tried several times to go through it with less realism, and I had to beg him to use all the seeming brutality demanded by the action.[15]

That New York production of The Queen of the Moulin Rouge was reported by a British publication as containing "a neck-breaking Apache dance...that for extraordinary and exaggerated movement far outdoes anything of its kind in London or Paris."[16]

The emergence of the Apache dance as a sensational highlight of the show led to favorable press items stating "Joseph C. Smith and Louise Alexander are already famous for what is termed, 'the most artistic character dance the stage has seen in years'."[17]

Praise of the Apache dance was directed at Smith and Alexander, while criticism of the dance was directed at the producer and the theater: "...why an 'Apache dance' anyway? Why must we have paraded before us the relations of persons so degraded that their common appellations cannot be spoken in polite conversation?"[18] or, "...the Apache dance...should not be permitted on any stage."[19]

After performing the dance within Queen of the Moulin Rouge for nearly three months, Smith and Alexander left the show to dance on the vaudeville circuit.[20] After observing their new vaudeville act the Variety reviewer wrote, "Smith and Alexander put up about the best thing that has been seen in the 'Apache' line. It is perhaps a little rough for some of the people with a nice sensitiveness, but it got over all right..."[21]

A reviewer who watched their vaudeville act in Baltimore listed the seven dances they performed in the act: a mechanical doll dance, La Kio, Temptation, Shadow, Apache dance, and French two-step.[22]

Temptress dancer

[edit]The temptation dance, or vampire dance, was primarily inspired by the conclusion of the 1909 hit Broadway play A Fool There Was starring Robert Hilliard with Katharine Kaelred as the vamp.[23] In that play's finale, Kaelred says "Before we part, kiss me, my fool!" Hilliard's character soon falls dead, at which point Kaelred laughs and tosses red rose petals on the corpse as the curtain falls.[24]

When Smith and Alexander danced their vaudeville act in June 1909 in Baltimore, they had to eliminate the temptation dance after the first performance because the vaudeville theater owner deemed the dance "vulgar and suggestive".[25]

In January 1910 Louise Alexander joined the cast of Ziegfeld's musical Miss Innocence starring Anna Held, then playing in Chicago. Louise Alexander's dance in that show was "The Dance of the Flirt", a temptation dance choreographed by Julian Mitchell.[26][27] According to the Chicago Tribune reviewer, Louise Alexander presented a "wanton leer that is quite a work of art" and she was "a wonder at seductive crouches".[28]

In June 1910 she was in Ziegfeld's Follies of 1910 where she danced the temptation dance again, now retitled "A Fool There Was", with Julian Mitchell as her dance partner.[29][30] One reviewer considered the dance essentially a variant of the Apache dance, "but this time a foolish man was entranced in the hypnotic waltz and a knowing woman did the enchanting."[31]

Critic Channing Pollock wrote that the dance was "rendered notable chiefly by Miss Alexander's costume, consisting of a pearl necklace and a becoming spotlight."[32]

In late 1911 she appeared in Peggy, an American adaptation of the successful London musical of the same name.[33][34] It was reported that Louise Alexander had financed the production. Her supporting role prompted one reviewer to write, "...Miss Alexander becomes more daring. She sings more and dances much."[35] The producer was Thomas W. Ryley, who had produced the hits Queen of the Moulin Rouge and Florodora, and the stage director was Ned Wayburn, but Peggy was not a success.[36]

Social exhibition dancer

[edit]In early 1914 she partnered with Clive Logan for social exhibition dancing in vaudeville, accompanied by a five-piece orchestra of black musicians.[37][38] When their tour reached Chicago a reviewer wrote, "They accomplish various swoops and whirls most gracefully...Miss Alexander and her young man are composed, almost capricious at times, and if they are not blissful they are at least contented."[39]

A Baltimore Sun reviewer wrote,

...There is only one 'star' dressing room on any stage, and electric signs are limited as to their capacity, and with such performers as Fanny Brice, Cathrine Countiss and Louise Alexander on one bill the troubles of a manager are evident. But in this case the patrons of the theatre benefit, for every one of these women, whose names are known wherever an electrical footlight glows in America, tries her best to win the greatest applause. Far be it from the writer, who is without steel armament impregnable to hatpins, to come out and boldly say that Miss So-and-So is the best on the bill...Miss Alexander is remembered for her creations of the Apache and Vampire dances, and she comes this time with dances "of the moment," which mean the Argentine tango, the hesitation waltz, the maxixe and the one-step. With her dancing partner, Clive Logan, she gives the best exhibition of dances seen here this season. What adds to their fascination is the orchestra, composed of five negroes who know how to play for the new dances...[40]

In May 1914 she partnered with John (Jack) Jarrott who had formerly been dancing with Joan Sawyer. It was announced that Alexander and Jarrott would dance in the "Congress of the World's Greatest Dancers" held at a theater in Boston, after which they planned travel to London and Continental cities before returning to America in the late Fall.[41] Regarding their dancing in Boston one reviewer wrote,

...Louise Alexander and John Jarrott, however, were the real features of the evening. Here was dancing that had the stamp of authority. Whatever the step, whatever the time, this couple showed remarkable pedal dexterity—if such an expression may be used—and absolute sense of rhythm. Their steps may have been more unusual than those of the rest, but the ease with which they were taken made them seem simplicity itself. To them, and particularly to Miss Alexander, dancing seemed as natural and as inevitable as walking.[42]

Louise Alexander, John Jarrott, and the five-piece orchestra soon sailed from New York to a London booking at the Princes' Hotel and Restaurant in Piccadilly.[43] Reportedly their dance performances at the Princes' during June and July 1914 were "packing the place nicely, and long before the theatres are out every table is taken."[44] While in London, Jarrott and Alexander also gave a dance exhibition at a party hosted by the Countess Lützow, wife of Count Francis Lützow.[45]

London newspaper ads for Princes' Restaurant in mid-July announced the "Special engagement of Miss L. Alexander and Mr. J. Jarrott with their celebrated coloured Band, who will entertain during supper until further notice."[46] That dance orchestra ensemble, led by Louis Mitchell, was the Southern Symphony Quintette, now renamed the Beaux Arts Symphony Quintette.[47] Due to the outbreak of World War I the dance team and orchestra returned to New York.[48]

In early December 1914 it was announced that Louise Alexander and John Jarrott would soon open a vaudeville tour, starting in Chicago.[49] But the act did not appear.[50] Louise Alexander sailed back to England on the Baltic, arriving at Liverpool on January 1, 1915.[51]

In March 1916 it was announced that a vaudeville opening was being arranged for Louise Alexander "with Rodolfo, late co-partner with Bonnie Glass, as her partner."[52]

In December 1916 Louise Alexander was reported dancing professionally at the Woodmansten Inn, in Westchester, New York, owned by Joseph L. Pani.[53]

Throughout January 1919, ads for the Café des Beaux Arts, in New York, stated that Louise Alexander was serving as hostess for their supper dances.[54]

When she returned from a trip to Paris in 1921 she was described in the press as, "Louise Alexander, formerly of the Follies, who recently opened a retail millinery and dressmaking shop, returning from her first buying trip."[55]

Private life

[edit]Shortly after moving to New York in late 1905 she married E. H. Lowe.[56] They divorced shortly afterward.[57]

In 1908 newspapers announced Louise Alexander's engagement to race car driver Lewis Strang and photos of them together were published.[58] The record-breaking[59] daredevil driver and the Follies girl instantly became a celebrity couple. Strang, who "always insisted on having ice cream before, during and after each big race,"[60] was the only American driver in the 1908 French Grand Prix; when he returned to New York she was reported greeting him at the dock.[61] He planned their wedding in September 1908 at Stamford, Connecticut, but she backed out when he arrived at the New York theater to pick her up after a Follies of 1908 performance. When reporters asked if she was married, she reportedly replied, "Married? Me? Well, not in this act."[62] A few days later Strang and Alexander were married in Chicago.[63][64] Strang wanted her to quit the stage; she wanted him to give up race car driving.[65] In 1910, during the time she was performing a temptress dance with Julian Mitchell, Mitchell's wife Bessie Clayton filed for divorce, citing Louise Alexander as corespondent.[66][67] Mitchell and Clayton later reconciled.[68] Louise Alexander divorced Strang in early 1911.[69] On July 20, 1911, Strang died in an automobile accident. Press rumors suggested he had deliberately sought death because of his failed marriage.[70]

New York cabaret venues were then increasing in popularity, and in late 1912 gossip columns began mentioning Louise Alexander and gambler Jay O'Brien dancing together.[71] Evelyn Nesbit recalled,

Night clubs as we knew them in the prohibition epoch did not exist, the cabaret idea being still in its embryo stage. Maxim's in W. 38th St., Bustanoby's in W. 39th, and Reisenweber's at Columbus Circle about completed the list. Their novelty attracted all the Broadway celebrities—Flo Ziegfeld and his most beautiful star, Lillian Lorraine; also Bonnie Glass, Al Davis, Jay O'Brien and Louise Alexander, Ann Pennington, Vera Maxwell and Beatrice Allen.[72]

Nesbit also recalled Jay and Louise were fellow passengers on the Olympic, which sailed from New York on May 3, 1913.[73] Jay and Louise returned on the Mauretania, arriving at New York from Liverpool on August 9, 1913. Listed on page 14 of the passenger list was Jay J. O'Brien and his "wife" Louise. On August 28, 1913, the following item appeared in Town Topics,

Reports that the good-looking and popular Jay O'Brien, once a famous gentleman jockey, has been married to a certain attractive little dancer are said to be absolutely false. It is true that Louise and Jay happened to cross on the same steamer, and that, almost six months later, they quite accidentally happened to return on the same ocean. But matrimony? He's not that kind of a Jay.[74]

In September 1913 Jay and Louise entered a dance contest at Holly Arms on Long Island, and won the first prize trophy.[75][76] A few months later it was reported that Mae Murray had replaced Louise Alexander as O'Brien's restaurant dance partner.[77] O'Brien and Murray married in 1916.

In 1917 Louise Alexander married restaurateur Joseph L. Pani.[78] She filed for divorce in 1918, alleging that her private apartments at the Woodmansten Inn had been used by Pani for "orgies".[79] The divorce was granted in 1919.[80]

In 1926 she married Park ("Pike") J. Larmon, a Dartmouth College graduate,[81] and the couple soon moved to Bayside, Long Island, New York. He died in 1957,[82] and Louise Alexander died the following year on October 28, 1958, at the age of 70.[83]

Legacy

[edit]Louise Alexander's version of the Apache dance contributed strongly to that dance's initial theatrical success.[84] Her other theatrical dances, including her exhibition ballroom dancing, helped spread the popularity of dances like the tango but had little enduring impact.[85]

Her 1914 employment of a black orchestral ensemble for playing her dance music, in venues where black musicians were infrequently seen, helped to advance acceptance of live black musicians into white-dominant culture.

References

[edit]- ^ "Born". Hartford Weekly Herald. July 4, 1888. p. 3. Retrieved May 30, 2021 – via Newspapers.com. No birth certificate was issued. This press item gives the birth date as June 30, but in passport applications she gave her birth date as June 29, 1888. On her 1920 passport application was written "Impossible to secure birth certificate as no official record was kept in Hartford."

- ^ "Brilliant Social Event". Hartford Weekly Herald. June 29, 1887. p. 3. Retrieved May 30, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "In Society". Owensboro Inquirer. June 18, 1905. p. 3. Retrieved May 30, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Earl and the Girl". The Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved May 30, 2021.

- ^ Boston Theater program, Week of October 22, 1906, The Social Whirl at the Internet Archive. Louise Alexander is listed among the "Manicures" and "Casino Girls".

- ^ "Auditorium theater program, Chicago, week of March 15, 1908, Follies of 1907". Chicago Public Library: Digital Collections. Retrieved May 30, 2021. Louise Alexander is named five times in the program.

- ^ "Follies of 1908". The Internet Broadway Database. Retrieved May 30, 2021. Louise Alexander's presence in the show was also mentioned in various newspapers when reporting on her engagement and marriage to Lewis Strang.

- ^ "Concerts et spectacles divers". La Lanterne. July 11, 1908. pp. 3–4. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Gallica.

- ^ "A Travers the Town: Independence Day", The Sporting Times, London, p. 2, July 11, 1908. Available at the British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Gossip from the Green-room", The Tatler, London, p. 144, November 11, 1908. "'La Danse des Apaches' is the excitement of the moment. In Paris, where it was introduced into one of the many revues, it quickly became the rage. Its popularity has now spread to London, and in the new Empire ballet A Day in Paris it is one of the principal features." Available at the British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Musical Comedy" (PDF). New York Press. December 13, 1908. p. sec. 2 p. 4. Retrieved June 5, 2021 – via Fulton History.

- ^ Smith, Joseph C. (May 30, 1914). "The Story of a Harlequin". The Saturday Evening Post. 186: 28.

- ^ Darnton, Charles (December 8, 1908). "The Queen of the Moulin Rouge is Just Pink". New York Evening World. p. 17. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Operetta Full of Girls". Brooklyn Times. December 8, 1908. p. 3. Retrieved June 3, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "'The Spirit of the Dance'—by the Dancers". New York Times. December 13, 1908. p. SM11. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com. The Times referred to the Alexander/Smith Apache dance as "The first appearance of the idea in this country", but while The Queen of the Moulin Rouge was still in the rehearsal stage, earlier New York stage appearances of the Apache dance had been presented, including by Alice Eis with Burt French, and by Valeska Suratt with Billy Gould.

- ^ "A Neck-Breaking Apache Dance", The Tatler, London, p. 359, March 31, 1909. Includes a full-page photo of Smith and Alexander performing the dance. Available at the British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "New York Amusements". Plainfield Courier-News. January 15, 1909. p. 11. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Queen of the Moulin Rouge". Variety. January 2, 1909. p. 14. Retrieved June 9, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Seen on the Stage: Gossip". Vogue. December 28, 1911. p. 1066. Available at ProQuest.

- ^ "Joe Smith and Louise Alexander..." Variety. March 27, 1909. p. 01. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Internet Archive. They were replaced in The Queen of the Moulin Rouge by Mons. Molasso and Mlle. Corio, who had been recently performing the Apache dance on vaudeville.

- ^ "New Acts of the Week: Smith and Alexander". Variety. April 3, 1909. p. 16. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Dancers at Maryland". Baltimore Sun. June 8, 1909. p. 7. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Flirting Princess". Chicago Inter Ocean. November 3, 1909. p. 6. Retrieved June 14, 2021 – via Newspapers.com. The vampire dance "follows the precedent of A Fool There Was faithfully." This was from a later review of the dance, when Smith was dancing with Adele Rowland.

- ^ "Gossip from Gotham". Evansville Press. April 3, 1909. p. 3. Retrieved June 14, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Baltimore". Variety. June 19, 1909. p. 29. Retrieved June 14, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Colonial Theater". Chicago Tribune. January 2, 1910. p. 7. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com. Meanwhile, Joseph C. Smith continued performing the Apache dance, now partnered with Adele Rowland, in The Flirting Princess.

- ^ "Colonial theater program, Chicago, week of January 9, 1910, Miss Innocence". Chicago Public Library: Digital Collections. Retrieved June 6, 2021.

- ^ "Music and the Drama". Chicago Tribune. January 5, 1910. p. 3, sec 2. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "The Drama". New York Tribune. June 21, 1910. p. 7. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Who's Who in Music and Drama. H. P. Hanaford. 1914. p. 372.

- ^ "Off the Stage to Amuse". Kansas City Star. July 3, 1910. p. 4C. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com. This comparison to the Apache dance only referred to the theme of dominant control, not physical brutality.

- ^ Pollock, Channing (September 1910). "The Summer Girl Shows: Follies of 1910". The Green Book Album. Chicago, Illinois: The Story-Press Corp.: 504. Retrieved June 13, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "The Week's Play Bills". Washington Herald. November 11, 1911. p. 2, sec. 3. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Dietz, Dan (2021). The Complete Book of 1910s Broadway Musicals. Rowman and Littlefield. ISBN 978-1538150276.

- ^ Fyles, Vanderheyden (December 17, 1911). ""Peggy" is not diverting". Louisville Courier-Journal. p. 4, sec. 4. Retrieved June 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com..

- ^ "New Productions at the Theaters". Anaconda Standard. January 14, 1912. p. 10, sec. 3. Retrieved June 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Amusements". New York Sun. February 15, 1914. p. 10, sec. 6. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Louise Alexander and Clive Logan". Variety. February 20, 1914. p. 19. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "About the Varieties; Lively Bill at the Palace". Chicago Tribune. April 14, 1914. p. 7. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Maryland". Baltimore Sun. March 24, 1914. p. 6. Retrieved June 5, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Both to Appear Here". Boston Globe. May 8, 1914. p. 13. Retrieved June 5, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Brooks, John (May 13, 1914), "Dancing Carnival at Boston Theatre", Boston Traveler. The article includes a nice photo of Alexander and Jarrott dancing. Available at myheritage.com

- ^ "Princes' Restaurant". The Observer (London). July 21, 1914. p. 10. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Tittle Tattle", The Sporting Times, London, p. 2, July 18, 1914. Available at the British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Dinners. Countess Lützow". The Times (London). June 23, 1914. p. 11. Retrieved June 7, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Princes' Hotel & Restaurant", Westminster Gazette, London, p. 9, July 14, 1914. Available at the British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Vance Lowry and the Classic Banjo?". classic-banjo.ning.com. January 7, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2021. The orchestra members were Louis Mitchell, Vance Lowry, Palmer Jones, Jesse Hope, and William Riley, all of whom arrived at Dover, England on board the Vaderland on June 8, 1914, per passenger list.

- ^ Berliner, Brett A. (Spring 2011). "Syncopated Hite: The Clef Club Negro Baseball Team in Jazz Age Paris". NINE: A Journal of Baseball History and Culture. 19 (2): 44–52. doi:10.1353/nin.2011.0009. S2CID 154156608.

- ^ "Louise Alexander and Jack Jarrott..." Variety. December 5, 1914. p. 7. Retrieved June 4, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Jack Jarrott and Louise Alexander..." Variety. January 16, 1915. p. 13. Retrieved June 4, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Per passenger list, as Louise S. Strang.

- ^ "Another effort to revive..." (PDF). The New York Dramatic Mirror. March 18, 1916. p. 11. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Fulton History.

- ^ "Cabarets". Variety. December 1, 1916. p. 8. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Restaurants" (PDF). New York Herald. January 10, 1919. p. 6, sec. 2. Retrieved June 7, 2021 – via Fulton History.

- ^ "Returning Buyers Describe Millinery Trends in Paris". Women's Wear. August 1, 1921. p. 2. Available at ProQuest.

- ^ "In Society". Owensboro Inquirer. January 9, 1906. p. 6. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com. Jennie's mother had divorced William Spalding and married Edward Miller earlier that year.

- ^ "Kentucky Girl". Hartford Herald. September 30, 1908. p. 1. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Louis Strang to Wed". New York Tribune. May 24, 1908. p. 10. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com."Lewis" was frequently misspelled as "Louis" in the press.

- ^ "His Track Record". Lancaster Teller. July 27, 1911. p. 5. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Louis Strang, one of the most..." New York Times. July 30, 1911. p. 28. Retrieved June 4, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Tells of Grand Prix". New York Tribune. July 17, 1908. p. 8. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bride Proved to be Balky". Oceola Evening Star. September 30, 1908. p. 2. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Auto Racer Figures in Hurry-Up Wedding". Oakland Tribune. October 7, 1908. p. 2. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ For a few anecdotes of their married life see: Leerhsen, Charles (2011). Blood and Smoke: A True Tale of Mystery, Mayhem and the Birth of the Indy 500. Simon & Schuster.

- ^ "Comments on Live Sports Topics". Buffalo Enquirer. July 21, 1911. p. 10. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com. "...The constant fear of becoming suddenly widowed became mental torture to the wife...But the keen eyed, steel nerved Strang only laughed at her fears and delighted in drawing from her little cries of terror while they were on the road in one of his big speed cars."

- ^ "The Hoodoo that Overtook the 'Mile-a-Minute Man'". Butte Miner. August 14, 1910. p. 21. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Bessie Clayton would Divorce Julien Mitchell". Elmira Star-Gazette. June 24, 1910. p. 1. Retrieved June 6, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "No Divorce, Says Bessie". San Francisco Examiner. December 24, 1911. p. 51. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Strang is Divorced" (PDF). Amsterdam Evening Recorder. January 19, 1911. p. 1. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Fulton History.

- ^ "Goes to Death in Auto; Lewis Strang thought to be Suicide". New Orleans Times Democrat. July 21, 1911. p. 51. Retrieved June 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Broadway Banter", Town Topics, New York, October 10, 1912. Available at the institutional archive Everyday Life & Women in America. "Jay O'Brien...manages to keep down his weight by the use of the turkey-trotting as a daily or rather nightly exercise with the lithe and lovely Louise Alexander as a partner."

- ^ "Evelyn Nesbit's Untold Story". New York Daily News. July 9, 1934. p. 23. Retrieved May 31, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Evelyn Nesbit's Untold Story". New York Daily News. July 10, 1934. p. 25. Retrieved June 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com. Nesbit and the couple "had met at Ziegfeld's parties."

- ^ "Broadway Banter", Town Topics, New York, August 28, 1913. Available at the institutional archive Everyday Life & Women in America.

- ^ "Contest for Holly Arms Cup Next Wednesday Evening" (PDF). Rockaway News. September 6, 1913. p. 1. Retrieved June 2, 2021 – via Fulton History. The date of the contest is given as September 10, 1913.

- ^ "Holly Arms Inn, Famous old Hotel, Sells for $150,000". Brooklyn Times. March 25, 1925. p. 9. Retrieved June 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com. "It was won by Louise Alexander, dancing with Jay O'Brien." Other clippings also confirm her victory in the contest.

- ^ "Broadway Banter", Town Topics, New York, February 6, 1914. Available at the institutional archive Everyday Life & Women in America. "Speaking of Louise Alexander reminds me that Jay O'Brien, who has been allowing Mae Murray to bask in the sunshine of his favor for the past few months since his breach with Louise..."

- ^ "Stage 'Queen' Seeks Divorce". Buffalo Times. October 29, 1918. p. 30. Retrieved June 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com. "...since their marriage in 1917..."

- ^ "Says Officials Took Part in High Jinks". Brooklyn Eagle. October 31, 1918. p. 3. Retrieved June 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mrs. Jos. Pani Gets Degree". Brooklyn Eagle. May 7, 1919. p. 4. Retrieved June 2, 2021 – via Newspapers.com. The final degree of divorce was issued on August 27, 1919, and noted on her 1920 passport application.

- ^ Fenno, Jesse K. (April 1927). "Class of 1916". The Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. XIX (6). Hanover, NH: Dartmouth Publishing Co.: 579. Retrieved June 2, 2021. The identity is confirmed by the obituary notices of Jennie Louise Spalding's mother, listing "Mrs. Park Larmon, New York City" as one of her surviving daughters, the others being accounted for.

- ^ "In Memorium: 1916". The Dartmouth Alumni Magazine. 50 (1). Brattleboro, VT: Dartmouth Secretaries Association: 92. October 1957. Retrieved June 3, 2021. "Park Jerrold Larmon...is survived by his widow, Louise Spalding Larmon..."

- ^ New York City Death Index, 1958; Probate Index Card for Louise S. Larmon, Case 6483-1958.

- ^ Malnig, Julie (1995). Dancing Till Dawn: A Century of Exhibition Ballroom Dance. New York University Press. ISBN 0814755283. "Smith and Alexander's performance of the Apache dance, in fact, did much to popularize the dance in this country." Theatrical popularity of the Apache dance peaked in 1910, per the number of mentions at newspapers.com each year.

- ^ Golden, Eve (2007). Vernon and Irene Castle's Ragtime Revolution. University Press of Kentucky. p. 73. ISBN 978-0813172699. "Who today remembers...Jack Jarrott and Louise Alexander...?"