Lolita (orca)

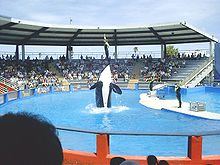

Lolita performing in 1998 | |

| Other name(s) | Tokitae[1] Toki Sk'aliCh'ehl-tenaut (Lummi nation)[2] |

|---|---|

| Species | orca (Orcinus orca) |

| Sex | female |

| Born | c. 1966[3] |

| Died | August 18, 2023 (aged 56–57)[3] Miami Seaquarium, Miami, Florida, United States |

| Years active | 1970–2022[4] |

| Known for | orca who lived at the Miami Seaquarium for 53 years |

| Weight | ≈7,000 lb (3,200 kg)[5] |

| Named after | Titular character in Nabokov's novel Lolita |

Lolita, also called Tokitae[6] or Toki for short, (c. 1966 – August 18, 2023),[3] was a captive female orca of the southern resident population captured from the wild in September 1970 and displayed at the Miami Seaquarium in Florida. She was retired from performing and taken off public display in 2022, and subsequently died in August 2023.[7] At the time of her death, Lolita was the second-oldest orca in captivity after Corky at SeaWorld San Diego.[8]

In March 2023, the Seaquarium announced that plans were being made for Lolita to be moved to a pen in the Salish Sea for the remainder of her life. On August 18, 2023, Lolita died from renal failure after exhibiting signs of distress over the prior two days.[9][10][11]

Life

[edit]Lolita was member of L Pod of the southern resident orcas, an endangered orca community that lives in the northeast Pacific Ocean. She was a close relative of L25 "Ocean Sun", who is the oldest member of the pod. After Lolita's death, L25 "is the only living whale from the 1960s and 1970s capture era."[3] Lolita was captured when she was an estimated three to six years old,[3] on August 8, 1970, in the Penn Cove capture in Puget Sound, Washington. Lolita was one of seven young orcas sold to oceanariums and marine mammal parks around the world from a capture of over eighty whales conducted by Ted Griffin and Don Goldsberry, partners in an operation known as Namu, Inc.[12][13][14][15]

Miami Seaquarium veterinarian Jesse White purchased Lolita for about $20,000.[16] Upon arrival at the Seaquarium, Lolita joined a male southern resident orca named Hugo, who was also captured from Puget Sound and had lived in the Seaquarium for two years before her arrival.[17]

The young orca was initially called "Tokitae," which in Chinook Jargon means "Bright day, pretty colors".[18] However, given the age difference between the young female and Hugo, she was renamed Lolita after the heroine in Vladimir Nabokov's novel.[19] The Lummi Nation of Washington refers to her as Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut, or, a female orca from an ancestral site in the Penn Cove area of the Salish Sea bioregion. They view her as a member of their "qwe 'lhol mechen," which translates to 'our relative under the water,' according to former tribal chairman Jeremiah "Jay" Julius.[20][18]

Lolita and Hugo lived together for ten years in the smallest orca tank in North America[2] known as the "Whale Bowl",[21] a tank 80-by-35-foot (24 by 11 m) by 20 feet (6 m) deep.[22] The pair mated many times (once to the point of suspending shows)[23] but they never produced any offspring.[24] Hugo appeared to suffer from a form of psychosis endemic in captive whales, and often rammed his head against the tank walls; he died in 1980 at 15 years old[2] of a brain aneurysm.[25] Lolita then shared the tank with a short-beaked common dolphin and a pilot whale during the 1980s and 1990s,[21] and later with a pair of Pacific white-sided dolphins, Li'i and Loke.[26][27]

In 2017, "the Miami Beach Commission voted unanimously for a symbolic resolution" to return Lolita to the place of her capture.[25] In August 2021, Cancun-based The Dolphin Company bought the Seaquarium. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) inspection report released a month later listed multiple serious problems with the conditions in which Lolita was held. The USDA issued a new license that stipulated that neither Lolita nor her dolphin companion Li'i could be on public display or used for staged exhibition shows.[28][4] The Dolphin Company announced that they would allow third-party veterinarians to examine Lolita.[29][30]

Planned return to natal waters

[edit]On March 30, 2023, the Miami Seaquarium and its new owner, The Dolphin Company, announced a legally binding agreement with the Friends of Toki (formerly Friends of Lolita) non-profit organization[31] to move her to an ocean sanctuary in the San Juan Islands[2] in the Pacific Northwest, to live out her life in her natal waters.[32][33][10][11] In a joint official statement, the partners in the agreement declared, "Returning Lolita to her home waters does not mean releasing her into the open ocean. She is expected to remain under human care, in a protected habitat, for the rest of her life. Lolita will continue to receive enrichment, high-quality nutrition, medical care and love, all according to the approved plans by federal authorities."[34] After being fed by humans for decades, it was questionable whether she could sustain a wild hunting lifestyle, according to scientific opinion.[35] Lolita's trainers reiterated that she had become "dependent on people."[36] The move to Washington could not have proceeded until permits were granted by several government agencies, including the US Department of Agriculture.[37] Allowing Lolita to leave the protected sanctuary would not have been approved without additional government permits.[35] Jason Colby, historian and author of a book on captured orcas, including Lolita,[38] cautioned against unreasonable expectations for a release back into the wild after decades in captivity. Colby said that having her live out her remaining days in a sea pen in 'home waters' would be successful enough. "I fear that when people see that she's being brought home, people will imagine it's just going to be a sort of Free Willy moment where she swims over and connects with her family. I can't imagine that happening," he said.[39]

Motivated by his daughter, the CEO of The Dolphin Company, Eduardo Albor, said, "More than just moving Lolita to a place where she will be better, she will become a symbol for us and the future generations."[40] The decision was made in cooperation with Miami-Dade County, and Indianapolis Colts owner and philanthropist Jim Irsay. The plan included acclimating and transporting Li'i and Loke, two Pacific white-sided dolphins who are her companions, with Lolita to the Salish Sea.[32][41] Li'i remained with Lolita during the process, while Loke was instead transferred with her offspring Elelo to Shedd Aquarium in August 2023.[42]

When Lolita would have been moved, the transportation method would have been similar to the one used to move her to Miami in 1970. She was being trained to swim into a custom–made stretcher that a crane would lift into a container filled with ice water. The container would then have gone onto a plane to Bellingham, Washington, from where it would be loaded onto a barge to transport her over water to a sea pen at a private location for the rest of her life. She would have continued to "receive round-the-clock medical care, security and feedings."[40] Initially, Lolita would be accommodated in an enclosure within the larger whale sanctuary before being allowed to swim in a netted area of about 15 acres (6 hectares).[35] In the Friends of Toki plan, "Trainers and veterinarians would tend and feed Lolita from floating platforms and boats, and a 24-hour security along a wider netted perimeter would keep boats away."[36] Much of the budget for the move would have been for her ongoing care in Washington state, particularly for the orca's huge gourmet appetite. Fresh local salmon, the southern resident orca diet, would have been her preferred food.[40] In 2023, Lolita's daily care at the Miami Seaquarium cost over $200,000 per month, assured by Jim Irsay.[43]

The process of moving all three animals was expected to take between 18 and 24 months and cost an estimated $15–20 million, the majority of which would have been bankrolled by Irsay.[32] Collaborating with The Dolphin Company, the multi-faceted Friends of Toki (formerly Friends of Lolita) organization includes marine mammal scientists Diana Reiss and Roger Payne, Lummi elder Squil-le-he-le (Raynell Morris), Charles Vinick of the Whale Sanctuary Project, and Florida Keys developer[36] and philanthropist Pritam Singh. Albor said, "Regardless of different positions, we can make this extraordinary agreement happen."[31]

Health late in life

[edit]As reported by the USDA in 2021, Lolita contracted a significant long-term illness before the Miami Seaquarium came under the management of The Dolphin Company,[44][31] and she had a lesion on her lung.[45] Lead veterinarian Tom Reidarson[46] said she "nearly died of pneumonia" in October 2022.[36] She received increased veterinary care in 2023.[37]

The monthly veterinary report of July 31, 2023, assessed that the pulmonary lesion was smaller. Bloodwork and chuff (blowhole exhalation samples) were unremarkable, with a very low white blood cell count in Lolita's chuff samples. In summary, the veterinarians were seeing incremental improvements in her health. Nonetheless, she was still fighting the chronic infection in her lung, and continued to receive daily Faropenem and antifungal medications.[45]

In addition to "feeding the highest quality salmon, herring, and capelin available on the market from 2023 catches," Lolita's care team had been introducing a small percentage of squid to her daily diet to benefit her gastrointestinal tract.[45]

Daily activity levels were steady. Trainers had been planning for Lolita's eventual move by shifting her activities away from performing tricks and stunts towards conditioning exercise to raise her fitness level.[36][45]

Improving water quality had been a focus for immediately improving Lolita's health and welfare. In May 2023, CEO Eduardo Albor said The Dolphin Company had invested more than $500,000 on upgrades to better filter the water and regulate water temperature.[47] These include an ozone generator to replace chlorine.[48][45] "New chillers can now get the temp down to mimic the waters of the Pacific Northwest, said trainer Michael Partica."[47] With very high temperatures in the Biscayne Bay source water, the two large portable chiller units enabled Lolita's pool temperature "to remain in the upper 50s [around 14°C], despite air and source water temperatures hovering in the upper 90s [around 37°C]. Round-the-clock maintenance of life support and water quality is being well managed by staff," the independent vets reported.[45]

Death

[edit]On August 18, 2023, Miami Seaquarium announced on their Facebook and Instagram that Lolita had died, apparently due to renal failure. They indicated that her health had been declining rapidly over the previous two days, and despite veterinarians' best efforts, she died that same afternoon.[49]

Later in the month, the Miami Seaquarium confirmed that, after the necropsy, Lolita's remains would be cremated and returned to her natal area, the Pacific Northwest.[50] On September 23, 2023, Lolita's remains were scattered off the coast of the Lummi Stommish Grounds in a traditional burial ceremony by members of the Lummi nation.[2][51]

On September 25, 2023, Miami Seaquarium announced that Li'i, the remaining 40-year-old male Pacific white-sided dolphin who was expected to be moved with Lolita, was relocated to SeaWorld San Antonio and reunited with family members and other Pacific white-sided dolphins to avoid remaining in solitary following Lolita's death.[52][53]

Necropsy

[edit]On August 29, the Miami Seaquarium released a statement regarding the necropsy process, which began with an examination on August 19. Analyses "could take more than four weeks." "'The necropsy was done in compliance with USDA and NOAA regulations,'" a spokesperson for the Seaquarium noted. "More than 15 veterinarians were reportedly assigned to the necropsy." "The August 19th examination took about 10 hours, according to the August 29th release, with samples taken to different labs for independent review." On October 17, the Miami Seaquarium released a statement that according to the necropsy report the orca's cause of death was due to a "progression of multiple chronic conditions including renal disease and pneumonia,".[54]

Reactions to death

[edit]Following her death, PETA president Ingrid Newkirk released a statement, saying "Lolita was denied even a minute of freedom from her grinding 53 years in captivity", urged "families to honor Lolita's memory by never visiting marine parks", and called for more marine parks to release dolphins into sea sanctuaries.[55] Save Lolita, a group that had campaigned for the orca's release, stated that Lolita "will forever remind us of the urgent need to protect our oceans and the magnificent creatures that call them home."[56] World Animal Protection US's executive director Lindsay Oliver released a statement, saying "She deserved the freedom of the open sea, not a life confined to a small tank. It's time for this industry to end, so no more animals have to suffer like this. Swim free, Tokitae."[57]

After Lolita's death, Ted Griffin, the man who captured her from the Puget Sound, said he had "no regrets" about capturing orcas, except those who died from being dropped by slings, overheating during transport, or injured in captivity.[58]

Activism and governmental actions

[edit]

Animal rights groups and anti-captivity activists asserted that Lolita was being subjected to cruelty.[22] In 2003, she was the subject of the documentary Lolita: Slave to Entertainment,[59][60] in which many anti-captivity activists, most notably Ric O'Barry (former Flipper dolphin trainer), argued against the conditions of her captivity and expressed a hope that she might be re-introduced to the wild.[61] O'Barry had trained and performed with the orca Hugo at the Miami Seaquarium.[62][63]

Urged by Orca Network,[64] in 2012, the Washington state government, which was sympathetic to the cause of returning her to her natal waters, named a new Washington state ferry under construction the MV Tokitae after Lolita's earlier name. The name also maintained the Washington tradition of naming ferries with regional tribal words. The vessel runs between Clinton and Mukilteo, north of Seattle, across a passage where Lolita and her community were chased during her capture.[65][66][67]

On January 17, 2015, thousands of protesters from all over the world gathered outside the Miami Seaquarium to demand Lolita's release and asked other supporters worldwide to tweet "#FreeLolita" on Twitter.[68]

In 2017, a USDA audit found that Lolita's tank did not meet the legal size requirements per federal law.[69]

In 2018 the Lummi Nation traveled to the Seaquarium with a totem pole carved for Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut (their name for Lolita), sang to her, and prayed that she would be returned to the Salish Sea. According to journalist Lynda Mapes, "The Seaquarium would not allow tribal members any closer than the public sidewalk outside the facility where the whale performs twice a day for food."[20] Seaquarium Curator Emeritus Robert Rose responded to the Lummi's journey, saying that the Lummi Nation "should be ashamed of themselves, they don't care about Lolita, they don't care about her best interests, they don't really care whether she lives or dies. To them, she is nothing more than a vehicle by which they promote their name, their political agenda, to obtain money and to gain media attention. Shame on them."[70] In response, environmental scholars and Julius argued that such statements are representative of a troubling pattern of discounting Native American knowledge and relationships, theft, and possession, which are "part and parcel of the possessive nature of settler colonialism."[71]

On September 24, 2020, the 50th anniversary of Lolita's arrival at the Seaquarium, tribal members of the Lummi Nation, joined by the local Seminole, traveled to Miami again, held a ceremony in support of Sk'aliCh'elh-tenaut, and demanded she be released to her native waters.[8] The totem pole journey was ongoing as of 2021.[72]

Some, such as the director of the University of British Columbia's Marine Mammal Research Unit, Andrew Trites, argued that Lolita was too old for life in the wild and that reintroducing her to the ocean after over fifty years in captivity would be "unethical" and a "death sentence".[73] However, other environmental scholars have posited that such arguments are representative of colonial conservation policies, stating that "The whales were killed and captured one at a time by settlers. If they can be killed or captured one at a time, there is no reason why the whales cannot be helped one at a time. Individual whales and pods can be cared for. 'Lolita' can be returned to her home waters."[71]

In March 2023, after the announcement of Lolita's move was decided, animal rights organizations, including PETA, World Animal Protection, and Animal Legal Defense Fund, openly supported the decision.[33][74]

Legal cases

[edit]In November 2011, the Animal Legal Defense Fund (ALDF), PETA, and three individuals filed a lawsuit against the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to end the exclusion of Lolita from the Endangered Species Act (ESA) of the Pacific Northwest's southern resident orcas. NMFS reviewed ALDF's joint petition and the thousands of comments submitted by the public and found the petition merited.[75] In February 2015, the NOAA announced it would issue a rule to include Lolita under the protection of the Endangered Species Act.[76] Previous to this, although the orca population that she was taken from is listed as endangered, as a captive animal, Lolita was exempted from this classification. This change did not impact her captivity.[77]

On March 18, 2014, a judge dismissed ALDF's case challenging Miami Seaquarium's Animal Welfare Act license to display captive orcas.[78]

In June 2014, ALDF filed a notice of appeal of the District Court decision that found the USDA had not violated the law when it renewed Miami Seaquarium's AWA exhibitor license.[79]

Cultural presence

[edit]Portions of Jennine Capó Crucet's novel Say Hello to My Little Friend, both about and set in the city of Miami, are narrated from the perspective of Lolita. The orca died while the book was in preparation and Capó Crucet, whose research led her to believe that orcas may be more intelligent than humans, hopes the novel will call attention to "the plight of captive marine mammals everywhere" and serve as a memorial to Lolita.[80]

See also

[edit]- List of captive orcas

- List of individual cetaceans

- Keiko (orca), the star of Free Willy, and the first captive orca released to the wild

References

[edit]- ^ "Lolita". Orca Network. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Gibson, Caitlin (December 5, 2023). "The call of Tokitae". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on December 5, 2023. Retrieved December 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Jones, Katie (August 24, 2023). "Toki will always be remembered". Center for Whale Research. Retrieved August 24, 2023.

- ^ a b Branton, Parker (March 4, 2022). "Feds approve deal affecting Miami Seaquarium's orca Lolita". local10.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ Mapes, Lynda (June 17, 2019). "Remembering Lolita, an orca taken nearly 49 years ago and still in captivity at the Miami Seaquarium". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 22, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- ^ "Lolita". Orca Network. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ "About Miami Seaquarium". Miami Seaquarium. Archived from the original on May 2, 2015. Retrieved May 19, 2015.

- ^ a b McKenna, Cara (September 26, 2020). "Native Americans honor Lolita the orca 50 years after capture: 'She was taken'". The Guardian. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ "Over the last two days, Toki started exhibiting serious signs of discomfort, which her full Miami Seaquarium and Friends of Toki medical team began treating immediately and aggressively..." Miami Seaquarium. August 18, 2023 – via Instagram.

- ^ a b Bartick, Alex (March 30, 2023). "Captured Southern Resident orca Lolita to return to Puget Sound after more than 50 years". komonews.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ a b Diaz, Johnny (March 30, 2023). "Lolita the Orca May Swim Free After Decades at Miami Seaquarium". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ "Adopt L-25 Ocean Sun". whalemuseum.org. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ "Lolita's Life Before Capture". Orca Network. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ Mapes, Lynda (August 20, 2023). "WA man who captured Tokitae says he has 'no regrets' after orca's death". The Seattle Times. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ "The Sad History Behind Orca Captures in the United States | World Animal Protection". www.worldanimalprotection.org.au. January 17, 2022. Retrieved October 8, 2023.

- ^ Samuels, Robert (September 15, 2010). "Lolita still thrives at Miami Seaquarium". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved August 9, 2011.

- ^ Sands, Cara (August 3, 2015). "One Dolphin's Story – Hugo". Dolphin Project. Archived from the original on August 6, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ a b Priest, Rena (2020). "A captive orca and a chance for our redemption". High Country News. Archived from the original on September 13, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ "Lolita officially named". The Miami News. November 30, 1970.

- ^ a b Mapes, Lynda (2018). "Lummi prayers, songs at Seaquarium just start of effort to free captive whale". Seattle Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Klinkenberg, Marty (December 15, 1989). "Killer Whale Cold to New Tankmate". Sun-Sentinel. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ a b "Lolita still thrives at Miami Seaquarium". Seattle Times. September 15, 2010. Archived from the original on July 14, 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2011.

- ^ "Sex Drive Stops Whale Show". The Palm Beach Post. December 4, 1977. Archived from the original on January 25, 2013.

- ^ "Lolita: happy, gentle, smart; weighs 4 tons". Boca Raton News. December 2, 1981. Archived from the original on November 16, 2021. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ^ a b Macdonald, Nancy (April 22, 2023). "The quest to free Lolita the orca from five decades in captivity". The Globe and Mail. Archived from the original on April 25, 2023. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- ^ Herrera, Chabeli (November 20, 2017). "Lolita may never go free. And that could be what's best for her, scientists say". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ Bernton, Hal (August 21, 2016). "Documents show unsettling look at orca Lolita's life in Seaquarium". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ "The Miami Seaquarium is ending shows with Lolita, its 56-year-old orca". NPR. Associated Press. March 4, 2022. Archived from the original on April 5, 2022. Retrieved April 5, 2022.

- ^ Ojo, Joseph (March 23, 2023). "Miami-Dade County announces Lolita the Orca will be examined by third party vets". WPLG Local10.com. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ McBain, James; Norman, Stephanie. "Health & Welfare Assessment May 2023" (pdf). Friends of Toki, Inc. Archived from the original on June 6, 2023. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Historic Initiative to Return Orca Lolita to Home Waters". The Whale Sanctuary Project. March 30, 2023. Archived from the original on April 10, 2023. Retrieved April 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c Harris, Alex (March 30, 2023). "Lolita may finally go free. 'Historic' deal clears way to move killer whale from Miami". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ a b Da Silva, Chantel (March 30, 2023). "Plan to return Lolita the orca to 'home waters' over 50 years after capture announced". nbcnews.com. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ "May 01, 2023 Efforts to Return Lolita to Her Home Waters" (pdf). Friends of Toki, Inc. Archived from the original on June 11, 2023. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Bringing Lolita home: How to release a long-captive orca?". KING-TV. Associated Press. April 4, 2023. Archived from the original on June 11, 2023. Retrieved June 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Hanks, Douglas (August 14, 2023). "For Lolita, there's finally a plan to leave her tank. But not for the open seas". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ^ a b Randhawa, PJ (April 3, 2023). "Orca in captivity in Miami for 5 decades may be returning home to Washington state". KING-TV. Archived from the original on June 11, 2023. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ Colby, Jason M. (2018). Orca: how we came to know and love the ocean's greatest predator. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190673116.

- ^ Bailey, Chelsea (March 31, 2023). "Miami Seaquarium is returning Lolita the killer whale to her home waters". BBC News. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ a b c Randhawa, PJ (May 23, 2023). "'She will become a symbol': Inside the fight to bring Tokitae home". KING-TV. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ Aguirre, Louis (March 30, 2023). "Miami Seaquarium announces plan to return orca Lolita to 'home waters'". WPLG Local10.com. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ Robertson, Linda (September 25, 2023). "Lolita's companion dolphin at Seaquarium moved to SeaWorld". The Miami Herald. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ "About Toki". Friends of Toki Inc. 2023. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ Balcomb-Bartok, Kelley (August 21, 2023). "Tokitae's death ends dream to return her home". Islands' Sounder. Retrieved August 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f McBain, James; Norman, Stephanie. "Health Progress 07/31/2023" (pdf). Friends of Toki, Inc. Archived from the original on August 13, 2023. Retrieved August 11, 2023.

- ^ "Our Team". Friends of Toki Inc. 2023. Retrieved August 17, 2023.

- ^ a b "Lolita the orca may return to Puget Sound, park says, but timeline uncertain". The Seattle Times. Associated Press. May 24, 2023. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ Vinick, Charles; Singh, Pritam. "Permitting Update 07/12/2023". Friends of Toki Inc. Archived from the original on August 16, 2023. Retrieved August 15, 2023.

- ^ "Lolita the orca dies at Miami Seaquarium after half-century in captivity". AP News. August 18, 2023. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ Jardine, Victoria (August 29, 2023). "Miami Seaquarium gives update on necropsy, cremation of orca Lolita". NBC 6 South Florida. Miami. Retrieved September 2, 2023.

- ^ "Ashes of orca Tokitae finally home after her death last month in Miami". September 22, 2023.

- ^ Alonso, Melissa (September 25, 2023). "Li'i the dolphin, companion to Lolita the orca, moved from Miami Seaquarium to SeaWorld San Antonio". CNN. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ Robertson, Linda (September 25, 2023). "Lolita's companion dolphin at Seaquarium moved to SeaWorld". The Miami Herald. Retrieved October 17, 2023.

- ^ "Beloved killer whale Lolita's cause of death revealed". NBC 6 South Florida. Miami. October 17, 2023. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ^ Powel, James; Lee Myers, Amanda (August 18, 2023). "'Lolita the whale' made famous by her five decades in captivity, dies before being freed". USA TODAY. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ Kim, Juliana (August 19, 2023). "Lolita, oldest orca held in captivity, dies before chance to return to the ocean". NPR. Retrieved August 21, 2023.

- ^ "Beloved Whale Lolita Dies Ahead of Release Back Into Natural Habitat: 'We Are Heartbroken'". Peoplemag. Retrieved August 22, 2023.

- ^ Berger, Knute. "Tokitae's death surfaced orcas' complicated history in the PNW". Crosscut. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ^ "Lolita the killer whale closer to freedom with inclusion on endangered list". The Guardian. January 25, 2015. Archived from the original on December 5, 2022. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ "Lolita: Slave to Entertainment". Houston Press. Archived from the original on August 19, 2023. Retrieved March 16, 2021.

- ^ Frizzelle, Christopher (September 30, 2015). "The Fight to Free Lolita". The Stranger. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ Colby, Jason M. (2018). Orca: how we came to know and love the ocean's greatest predator. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 311. ISBN 9780190673116.

- ^ "About Ric O'Barry". Ric O'Barry's Dolphin Project. 2023. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ Garrett, Howard (November 14, 2012). "Lolita Update #130". Freeland, Washington: Orca Network. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ "Two new ferries named Samish, Tokitae". The Everett Herald. Everett, Washington. Associated Press. November 13, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ Colby, Jason M. (2018). Orca: how we came to know and love the ocean's greatest predator. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 308. ISBN 9780190673116.

- ^ "Clinton Ferry Schedule 2023". Clinton Ferry Schedule. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ^ Rodriguez, Laura (January 17, 2015). "Protesters March to Free Orca Lolita from Miami Seaquarium". NBC Miami. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ^ Herrera, Chabeli (June 7, 2016). "Lolita's tank at the Seaquarium may be too small after all, a new USDA audit finds". Miami Herald. Archived from the original on April 22, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ Rose, Robert (2018). "Lolita Update From Our Curator Emeritus, Robert Rose". Facebook. Archived from the original on May 12, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ a b Guernsey, Paul J.; Keeler, Kyle; Julius, Jeremiah 'Jay' (July 30, 2021). "How the Lummi Nation Revealed the Limits of Species and Habitats as Conservation Values in the Endangered Species Act: Healing as Indigenous Conservation". Ethics, Policy & Environment. 24 (3): 266–282. doi:10.1080/21550085.2021.1955605. ISSN 2155-0085. S2CID 238820693. Archived from the original on September 13, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ Mapes, Lynda (2021). "Lummi Nation totem pole arrives in D.C. after journey to sacred lands across U.S." Seattle Times. Archived from the original on September 13, 2021. Retrieved September 13, 2021.

- ^ Pawson, Chad (May 28, 2018). "B.C. marine mammal expert says moving killer whale from Miami a death sentence". cbc.ca. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved April 22, 2021.

- ^ Bender, Kelli (March 30, 2023). "Florida Aquarium Plans to Return Lolita the Orca to Her 'Home Waters' After 50 Years in Captivity". People. Archived from the original on March 30, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ "Make a Splash: Free Lolita!". ALDF. Archived from the original on November 12, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ "NOAA: Lolita Now Covered Under Endangered Species Act". CBS News. February 4, 2015. Archived from the original on March 31, 2023. Retrieved March 31, 2023.

- ^ "Captive killer whale included in endangered listing". NOAA. February 4, 2015. Archived from the original on February 7, 2015. Retrieved February 7, 2015.

- ^ "Sequarium Docket". March 18, 2014. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014.

- ^ "Judge's Refusal to Review Seaquarium's Violations of Law Prompts Court Appeal". ALDF. Archived from the original on July 22, 2014. Retrieved July 16, 2014.

- ^ Pfeiffer, Sacha (March 19, 2024). "Jennine Capó Crucet aimed to write an elegy of Miami in new 'Scarface'-inspired novel". NPR.

External links

[edit]- Sacred Sea Lolita news from Lummi Nation conservation non-profit

- Lolita: Slave to Entertainment film listed on IMDb