Lokori

Lokori | |

|---|---|

| Coordinates: 1°57′N 36°01′E / 1.95°N 36.02°E | |

| Country | Kenya |

| Province | Rift Valley Province |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (EAT) |

Lokori is a Turkana settlement in Kenya's North Eastern Province, adjacent to the Kerio River. The settlement's inhabitants are traditionally pastoralists. Lokori is home to a number of prehistoric Namoratunga rock art and burial sites.

Geography

[edit]Lokori is located in southern Turkana District, south of Lake Turkana, and less than 1 kilometer southwest of the banks of the Kerio River.[1] The town is south of Kitale, Lokichar and Loperot, northeast of South Turkana National Reserve, and located at the intersection of the C113 and C46 highways. The Loriu Plateau lies to the east.[2]

Geology

[edit]Lokori is located in the Turkana Basin, a part of the East African Rift Valley. Sediments and volcanic rocks around Lokori in south Turkana range in age from 17 million years old to present. Volcanic activity appears to have occurred in 6 major instances of eruption.[3]

Ecology

[edit]Ecologically, Lokori and the surrounding area are fairly representative of the habitats and land types found throughout southern Turkana.[1] Annual precipitation has been measured at 283 mm, and is highly variable. Most rainfall occurs from March through May.[3] Droughts are common in Lokori: in one 20-month period from 1979–81, only 149mm of rain were recorded.[2] The region may be classified as a true semi-desert. Temperatures as high as 115 F have been recorded in nearby Suguta.[3]

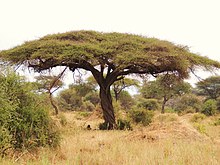

Lokori includes lava desert areas covered by basalt and sparsely vegetated by only a few Acacia reficiens, Euphorbia bush, Blepharis fruticulosa and grasses including Aristida mutabilis. Occasional water courses include a greater variety of plants including Acacia nubica, Acacia tortilis, Maerua oblongifolia, Salvadora persica, and grasses including Sporobolus and Chloris gayana. When lava outcrops are located within river vallies, boulders are interspersed by soil supporting rich vegetation including Adenium, Maerua, and Balanites.[1]

Lokori also includes alluvial flats characterized by large wadis, rivers, and flood zones anywhere from meters to kilometers in length. These flats are vegetated by thickets of Acacia nubica and by lesser quantities of Euphorbia, Blepharis, Carallumba dummeri and Jatropha villosa. Grasses in these flats include Aristida and Chrysopogon aucheri. The largest flats along the Kerio include denser vegetation including Coridia. Large areas around Lokori are dominated by stands or thickets of Salvadora, Cordia and Acacia tortilis.[1]

In the most densely vegetated areas along riverbanks and beneath Acacia tortilis stands, Withania somnifera, Maerua, Acyranthes aspersa and Cynodon dactylon can be found. Figs including Ficus sycamorus and the milkweed Calotropis procera are found.[1]

Tilapia and Clarias are found in the Kerio and Suguta rivers, and crocodile in the Suguta.[3] Thirteen species of lizard have been recorded in the vicinity of Lokori, with reptilian biomass higher in more arid zones. Discovered species resemble Somali fauna.[1] Mammals include baboons, black faced vervet monkeys, Grant's gazelle, leopard, silver-backed jackals, bat-eared fox, and striped hyena.[3]

Prehistory

[edit]

Two of three large Namoratunga rock art and cemetery sites found in Turkana are located just north of Lokori. Both sites are located on basalt lava outcrops, about 1 kilometer from one another. One site contains 162 burials, and the other contains 11. Each burial may contain over 10 tons of rock, and is composed of an outer circle of massive stone slabs rising up above the ground, and the interior of each circle is layered with horizontal stone slabs. Buried beneath the ground, a massive stone slab marks the entrance to underground burial pits. While females and children are buried at the sites, males constitute the majority of subjects, and only male graves are engraved. All those buried are oriented in one of the cardinal directions, and never in between.[4]

The Namoratunga sites contain a large quantity of engraved rock art, including geometric designs linked to branding symbols used by modern east African pastoralists. Domesticated cattle, sheep and goat teeth are found in most graves. The Namoratunga grave sites are unusual in the region and most similar to cairn constructions of southern Ethiopian cushitic peoples, including the Konso people. Radiocarbon measurements suggest the graves were made some time around 335 B.C.[4]

The Maasai people, though now living further south, are recorded to have lived near Lokori in the northern Kerio river valley as recently as 1400 A.D. Ceramic cultures associated with Nilotic people like the Maasai or Turkana may have first moved into the region between 450-1100 A.D., if not earlier. Ceramics belonging to these cultures are identified by "Turkwell Tradition" pottery characterized by repeated, deep horizontal grooves, and further grooves that radiate from these, likely produced by fish spines.[4] Major Turkwell tradition sites in the region are Apeget and Lopoy both approximately 100 km north of Lokori, above the Turkwel River.[4]

Settlement

[edit]

Today Lokori is settled by the traditionally nomadic and pastoralist Turkana people,[3] with many belonging to the Ngisonyoka Turkana group.[2] Pastoralists around Lokori typically raise camels, cattle, sheep and goats. These are a measure of wealth, and are also used to trade for cash or maize, or traditionally exploited for consumption of milk and blood.[3]

One regional study found that in 1980-85, pastoralists outside Lokori lost over 50% of their stock to drought, with cattle especially affected, and camels most resilient. The study found that Lokori pastoralists were able to regain pre-drought stock numbers after three years of normal rains.[2]

Consistent with patterns found in the tropics, a 1974 study investigating hepatitis B prevalence found that 12% of the Turkana people in Lokori tested positive for the HB ag antigen.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f Western, David (1974). "The distribution, density and biomass density of lizards in a semi-arid environment of northern Kenya". East African Wildlife Journal. 12: 49–62. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.1974.tb00106.x.

- ^ a b c d McCabe, Terrence (1987). "Drought and Recovery: Livestock Dynamics among the Ngisonyoka Turkana of Kenya". Human Ecology. 15 (4): 371–389. doi:10.1007/bf00887997.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harvey, Peter (1997). The Geology of the Area to the South of Lokori, South Turkana, Kenya. Leicester University.

- ^ a b c d Lynch, BM; Robbins, LH (1979). "Cushitic and Nilotic Prehistory: New Archaeological Evidence from North-West Kenya". Journal of African History. 20 (3): 319–328. doi:10.1017/s0021853700017333.

- ^ Mutanda, Labius; Mufson, Maurice (1974). "Hepatitis B Antigenemia in Remote Tribes of Northern Kenya, Northern Liberia, and Northern Rhodesia". Journal of Infectious Diseases. 130 (4): 406–408. doi:10.1093/infdis/130.4.406. PMID 4443616.