Livistona humilis

| Livistona humilis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae |

| Tribe: | Trachycarpeae |

| Genus: | Livistona |

| Species: | L. humilis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Livistona humilis | |

Livistona humilis, the sand palm, is an Australian plant species of the family Arecaceae. It is a small, slender palm, growing to about 7 m tall and 5–8 cm dbh. It has 8 to 15 fan-shaped leaves, 30–50 cm long with petioles 40–70 cm long. It is endemic to the Top End of the Northern Territory in Australia. Genetic investigation suggests that its closest relative is Livistona inermis.[2] This palm is fire tolerant and usually grows in environments where it is exposed to frequent fires.[3]

Livistona humilis is dioecious[4] and sexually dimorphic. The flower stalks on the female plant are erect and up to 230 cm long, while the male plant's flower stalks are up to 180 cm long and curved. The flowers are small and yellow, 2 mm to 4 mm across. Fruit is shiny purple black, ellipsoid, pyriform, or obovoid, 11–19 mm long and 8–10 mm in diameter.[2]

Taxonomy

[edit]The first description of the species was by Robert Brown in his Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae (1810). A partial taxonomic revision in 1963 resolved the typification of the genus, established by Brown to accommodate this species and Livistona inermis; Livistona humilis is recognised as the type for the genus Livistona. His collaborator Ferdinand Bauer, the botanist and master illustrator, produced artworks to accompany Brown's descriptions, but these were not published until 1838.[5] The holotype of this species was collected in January 1803 by Robert Brown from Morgans Island in the Gulf of Carpentaria.[2]

The name comes from the Latin humilis, meaning "low" – referring to its small stature.[6]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The sand palm is endemic to the north of the Northern Territory of Australia, from the Fitzmaurice River to Cape Arnhem and inland as far as Katherine. It occurs in open forest and woodland up to about 240 m above sea level, most commonly on deep sandy soils and sandy lateritic soils, but it is found in various soils and rocky areas. It frequently grows beneath eucalypt understorey.[2][3]

Phenology

[edit]Flowering: September to May. Fruiting: January to June.[3]

In Aboriginal culture

[edit]Aboriginal people use this palm in a number of ways. The fruits are edible. The heart (central growing tip) can be eaten, either raw or roasted. The core of the stem is pounded and made into a drink which is used to treat coughs, colds, chest infections, diarrhea, and tuberculosis. Backache is treated with the crushed stem core. The fruit and growing shoot can be used as a black or purple dye.[3] In the Yolŋu language of East Arnhem Land the palm is called dhalpi',[7] while in the Kunwinjku language of West Arnhem Land it is known as mankurlurrudj, or alternatively marrabbi in the eastern Kuninjku dialect.[8]

Conservation status

[edit]Not currently included in the Northern Territory threatened species list.[9]

Gallery

[edit]-

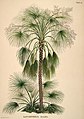

Ferdinand Bauer in Martius Historia naturalis palmarum (1838) Plate 110

-

Bauer's second illustration of the species. Plate 111.

References

[edit]- ^ Brown, Robert (1810). Prodromus floræ Novæ Hollandiæ et Insulæ Van-Diemen : exhibens characteres plantarum quas annis 1802-1805 / (in Latin). typis R. Taylor et socii.

- ^ a b c d Dowe, JL (2010), Australian Palms : Biogeography, Ecology and Systematics, Melbourne, Vic: CSIRO Publishing, pp. 110–112, ISBN 9780643096158

- ^ a b c d Brock, John (2001), Native plants of northern Australia, Frenchs Forest, NSW: Reed New Holland, p. 238, ISBN 1877069248

- ^ Dowe, John Leslie (2009). "A taxonomic account of Livistona R.Br. (Arecaceae)" (PDF). Gardens' Bulletin Singapore. 60: 235–237. Retrieved 13 October 2020.

- ^ Rodd, A. (21 December 1998). "Revision of Livistona (Arecaceae) in Australia". Telopea. 8 (1): 49–153. doi:10.7751/telopea19982015.

- ^ Napier, D; Smith, N; Alford, L; Brown, J (2012), Common Plants of Australia's Top End, South Australia: Gecko Books, pp. 50–51, ISBN 9780980852523

- ^ Zorc, David. "dhalpi(')". Yolŋu Matha Dictionary. Charles Darwin University. Retrieved 13 July 2019.

- ^ Garde, Murray. "mankurlurrudj". Bininj Kunwok online dictionary. Bininj Kunwok Regional Language Centre. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- ^ Department of Land Resource Management (2015), Threatened Species List, Northern Territory Government, archived from the original on 2 April 2015, retrieved 27 March 2015