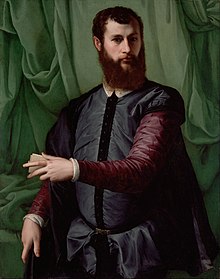

Lionardo Salviati

Lionardo Salviati (1539–1589) was a leading Italian philologist of the sixteenth century.[1] He came from an illustrious Florentine family closely linked with the Medici. Salviati became consul of the Florentine Academy in 1566, and played a key role in the founding of the Accademia della Crusca, with its project of creating a dictionary, which was completed after his death.[2]

Salviati immersed himself in philological and linguistic research from a young age and produced a number of works. Some of these were published during his lifetime, such as the Oration in Praise of Florentine Speech (1564) and Remarks on the Language of the Decameron (2 vols, 1584–1586). Salviati also published two comedies, The Crab (1566) and The Thorn (1592), lessons, treatises, and editions of texts by other authors. He also wrote numerous polemical pamphlets against Torquato Tasso under different pseudonyms, mostly using the nickname he adopted on joining the Accademia della Crusca, 'Infarinato' ('covered in flour').[3] Other works remained unpublished and exist only in manuscript form, such as his grammar Rules of Tuscan Speech (1576–1577), a translation and commentary on Aristotle's Poetics (preserved at the National Library of Florence), a collection of Tuscan proverbs (preserved at the Biblioteca Comunale Ariostea in Ferrara) and linguistic corrections to Il Pastor Fido by Giovanni Battista Guarini (1586).[3]

Salviati was recognized by his contemporaries as a master of oratory and many of his speeches were published both as one-off pamphlets and in a larger anthology: The first book of the Speeches of Cavalier Lionardo Salviati (Florence 1575). Particularly noteworthy are his speeches delivered at important events, in particular at the funerals of Benedetto Varchi,[4] Michelangelo Buonarroti,[5] Piero Vettori[6] and the Grand Duke Cosimo de 'Medici.[7][3]

Family background and early career (1539–1569)

[edit]Lionardo Salviati was born in Florence on 27 June 1539, the fourth child of Giovambattista di Lionardo Salviati and Ginevra, daughter of Carlo d'Antonio Corbinelli. His family, though not rich, had ancient origins and close connexions with the Medici. His humanist education was entrusted to Piero Vettori and he also enjoyed the support of Vincenzio Borghini and Benedetto Varchi.[8]

He first came to public attention with the composition in 1583 of three memorial orations ('confortatorie') for Garzia de' Medici,[7]: 9 deceased son of Grand Duke Cosimo, which earned him the esteem of the grieving family.[9] Later in 1563 he went to Pisa for several months for unknown reasons, where he fell seriously ill for a time. Salviati's tutor Vettori was also a literary advisor to (it) Baccio Valori, consul of the Florentine Academy, and through this connnexion Salviati was invited to deliver his famous Oration in Praise of Tuscan Speech on April 30, 1564. Two days later, on 1 May 1564, he published a discourse on poetry dedicated to Francesco de' Medici, the oldest son of Grand Duke Cosimo, who had just assumed the regency for his ailing father. His services to the Medici were not however rewarded by the favours he desired: in 1564 Salviati was passed over for the position of canon of Prato.[8]

In 1565 Salviati was admitted to the Florentine Academy, and together with Varchi, appointed counselor to the new consul, Bastiano Antinori. Varchi died in December of the same year, and the funeral oration Salviati wrote and delivered for him was so outstanding that he was appointed consul himself in March 1566. In addition to performing the routine activities of this post and composing occasional works (such as the translation from Latin of Vettori's oration for the Grand Duchess Joanna of Austria), Salviati also began his project for a new edition of Boccaccio’s Decameron.[8] This work had been placed on the Index of prohibited books in 1559 because of its anticlerical character. Various scholars had plans to purge the work of views unacceptable to the Church and to ‘purify’ it's vulgar language. Both Salviati and Grand Duke Cosimo felt that it was a matter of Florentine honour that the work should not be banned outright and that a revised edition should be the work of Florentine scholarship.[10] Until this work could be undertaken, Salviati persuaded Cosimo to block a Venetian project to issue a revised edition.[8]

Search for patronage (1569–1577)

[edit]Salviati concluded his consulate with a valedictory oration dedicated to Vincenzo Borghini. His devotion to the Academy and to the Medici earned him, in June 1569, the honour of knight chaplain of the Order of Saint Stephen which he was presumably awarded after spending an obligatory year of service at its headquarters in Pisa. In August 1569 Pope Pius V elevated Tuscany from a Duchy to a Grand Duchy and Salviati wrote an oration for the coronation of Cosimo de' Medici.[3]

This knighthood was prestigious but did not provide an income. For this reason Salviati, while undertaking a variety of tasks assigned by the Order, offered his services to the dukes of Ferrara and Parma in May 1570, but without success. In March 1574 he was appointed commissioner of the Order in Florence, a burdensome position that he maintained until its abolition in July 1575. In April 1575 he was in charge of the funeral oration for Cosimo de' Medici in Pisa. The new Grand Duke, Francesco, as not inclined to show him any favour, so Salviati considered entering the service of Antonio Maria Salviati, papal nuncio to France, to whom he dedicated his Five Lessons inspired by sonnet 99 of Petrarch’s Il Canzoniere in June 1575.[3]

This approach, together with the dream of becoming ambassador to Ferrara, was eventually set aside in the hope of becoming a courtier of Alfonso II d’Este, to whom he dedicated his Commentary on the Poetics, through the good offices of Ferrara’s ambassador to Tuscany, Ercole Cortile. Negotiations for this position opened in December 1575, but were never concluded; and the Commentary on the Poetics was never finished. In the summer of 1576, as part of Salviati’s campaign to secure favour from the d’Estes, Orazio Capponi put him in contact with the court poet in Ferrara, Torquato Tasso, who was struggling to revise his Jerusalem Delivered. Salviati read part of it and sent Tasso a polite letter recording his largely positive response. He also composed several essays defending the work from criticism about the excessive ornamentation in its language, and offered to make it honourable mention of it in his Commentary on the Poetics.[3]

Period in Rome (1577–1582)

[edit]Salviati eventually entered the service of Giacomo Boncompagni - General of the Church, son of the reigning Pope Gregory XIII - whom he had met in September 1577 at the baptism of Filippo de' Medici. Later he moved to Rome, remaining there, though with frequent returns to Florence, until 1582. In Rome, Salviati also performed the functions of "receiver" of the Order of St. Stephen between 1578 and 1581. Apart from this, he continued his scholarly pursuits: most importantly, he obtained the commission to produce a new edition of the Decameron, which was to replace that of 1573, which had also been placed on the Index. Thanks to Boncompagni, the Inquisition agreed to this project and Salviati was charged with it by the Grand Duke on August 9, 1580.[8]

Salviati had already contributed to the "Deputies’ edition" of 1573, but this new version was a much more thorough-going project, involving the wholesale rewriting of 'inconvenient' sections and inserting moralizing commentary. The censorship was plain to the reader - the new edition used a variety of typographic styles and provided a table in an appendix with "Some differences between the other text from the year 1573 and our own". With a dedication to Buoncompagni, it was published in 1582 by Giunti, first in Venice and then a few months later in Florence, with numerous corrections.[8]

Formation of the Accademia della Crusca (1582–1584)

[edit]The Accademia della Crusca developed out of the informal meetings of a group of Florentine intellectuals (including Antonio Francesco Grazzini, it:Giovan Battista Deti, it:Bernardo Zanchini, Bernardo Canigiani and it:Bastiano de' Rossi) between 1570 and 1580 in the Giunti bookshop near the chapel of S. Biagio of Badia. They self-deprecatingly called themselves "Crusconi" (‘bran flakes’) in contrast to the solemnity surrounding the erudite discussions of the Florentine Academy; however in 1582, on the initiative of Salviati, the Crusconi gave their gathering a formal status by naming themselves also as an Accademia.[11] In the archive of the Accademia della Crusca there is a hand-written document by Piero de 'Bardi that provides the minutes (autumn 1582) of the memorable foundation meeting and the speech by Salviati.[3]

Salviati interpreted the name crusca (bran) in a new way, namely that the role of the Academy was to separate the wheat of literary and linguistic quality from the chaff of ordinary or uninformed language. Salviati helped to give the Academy a new linguistic direction, promoting the Florentine language according to the model of Pietro Bembo, who idealized the 14th-century Italian authors, especially Boccaccio and Petrarch.[3][11]

Salviati also promoted the creation of a Vocabolario (dictionary), in which he planned to gather "all the words and manners of speech, which we have found in the best writings from before 1400".[12] The Vocabolario was not completed and published until after Salviati's death, but in the Foreword, the academicians announced that they intended to adhere to Salviati's views on grammar and spelling. They also followed him above all in the philological approach of their work and in the choice of texts they cited as authorities; the table of authors referred to in the Vocabulario closely matched the list provided by Salviati in his work Warnings.[3]

In 1584, under the pseudonym Ormannozzo Rigogoli, Salviati published his dialogue Il Lasca, a "cruscata" which argued that it was of no importance whether a story was true.[13] By then his energies were absorbed by a work of another tenor, the Remarks on the Language of the Decameron ; in March 1584 he went to Rome to give a copy of the first volume to its dedicatee Buoncompagni, from whose service he then took leave.[8]

Disputes over Tasso (1584–1586)

[edit]Late 1584 saw the publication of Il Carrafa, or the truth of the epic poem by (it) Camillo Pellegrino, which discussed whether Ludovico Ariosto or Torquato Tasso had achieved primacy in epic poetry; it declared the winner was Tasso's Gerusaleme Liberata, because of its respect of the unity of action, the balance between history and fantasy and the morality of the Christian characters; Orlando Furioso in contrast, was criticised for lacking unity and verisimilitude, as well as for its licentious episodes.[14][8]

In February 1585 there appeared the Defence of the Furioso Orlando, signed collectively by the Academicians of the Crusca, but actually written by Salviati with the collaboration of Bastiano de' Rossi. Preceded by a dedication to it:Orazio Ricasoli Rucellai and a preamble to the readers (written by de 'Rossi), the Defence was an attack on the language of Tasso's poem, whose Latinisms and 'impure' forms were considered detrimental to Tuscan 'purity'. For similar reasons, the L'Amadigi (1560) of Bernardo Tasso, who had died long before (in 1569), was bitterly criticized. Compared to Orlando Furioso, Gerusaleme Liberata was also judged to be lacking in inventiveness.[8][15]

From the (it) hospital of S. Anna in Ferrara, where he was imprisoned, Tasso responded with an Apologia for his poem. In this, after speaking up for his fathers work, he meticulously defended his own. After a number of other writers intervened in the controversy, Salviati, using his Accademia Della Crusca name ‘Infarinato’, published a forceful and polemical response to Tasso's Apologia on 10 September 1585, dedicated to the Grand Duke. This emphasized the superiority of the invention over imitation, and of fantasy over history, denying that the poet's task was to express the truth. At the same time Salviati reiterated criticism of both L’Amadigi and Gerusalemme Liberata, extolling the excellence of the poems of Matteo Maria Boiardo and Ariosto and, for the purity of its language, the Morgante of Luigi Pulci.[8]

Tasso returned to the controversy in his Giudicio sovra la Gerusalemme riformata (published posthumously in 1666). Salviati responded again with an answer (1588, dedicated to Alfonso II d'Este) to Pellegrino's Replica.[14] Also his work was the Considerations against a pamphlet in defense of Tasso written by Giulio Ottonelli, which Salviati published under the pseudonym Carlo Fioretti in 1586.[8]

Ferrara and final year (1587–1589)

[edit]In 1586 Salviati published the second volume of the Remarks on the Language of the Decameron in Florence, in two books: the first dedicated to the noun, the second to the preposition and the article. Then, through the good offices of Ercole Cortile and after intense negotiation which ended in December of that year, Salviati was invited into the service of Alfonso II d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, to write a new history of the d’Este dynasty. An initial part of this was included in the funeral oration for Cardinal Luigi d'Este, who died in Rome, printed in February 1587. In March, Salviati resigned as consul of the Accademia Della Crusca and went to Ferrara, with the additional responsibility of reader of "Aristotle’s Morals". He composed the funeral oration for Don Alfonso d'Este, the uncle of the duke, who died in November 1587, which he read publicly.[8]

Back in Tuscany in the summer of 1588, he was struck by violent fevers from which he never recovered. The last months of his life were spent with the relief of the aid he received from Alfonso II, to whom he bequeathed his library and manuscripts. Conducted in the spring of 1589 in the monastery of S. Maria Angeli, he died there on the night between 11 and 12 July.[8]

Overview of Salviati's work

[edit]Comedies

[edit]Salviati took part in the organising of several court masques, and while still consul of the Florentine Academy, he composed a comedy for the Carnival of 1567. The Crab (‘Il Granchio’) is in five acts, presented as a gift to Tommaso Del Nero, who in turn is the author of the dedication to Francesco de 'Medici. The Prologue explains that it is written in loose hendecasyllables, as suggested by Aristote's Poetics.[3]

A second comedy, The Thorn (La Spina), written at an uncertain date, was printed posthumously in Ferrara in 1592, with a dedication to Giovanni Battista Laderchi, secretary of Alfonso II d'Este. The text is in prose, and considering Salviati's preference for comedies in verse, it is possible that the surviving version is only a draft.[3]

Both plays followed the rules of classical poetics but were written in idiomatic Florentine, thus demonstrating how refined contemporary language could accommodate traditional forms.[15]

Oration in Praise of Florentine Speech (1564)

[edit]At a solemn meeting of the Florentine Academy, Salviati, then aged twenty-four, paid tribute to his own language with the stated aim of bringing about a drastic change of attitude among the academicians. The nub of his argument was that inherent virtue or an illustrious literary tradition were not sufficient for a language to thrive and prosper. Florentine speech was a living language with authors including "that wonder and miracle", Dante; however a language is only affirmed if the speaker is aware of its value and if those with position and authority are committed to its recognition and dissemination. Florentine speech had been awakened "from sleep" at the beginning of the sixteenth century by Pietro Bembo, but now needed a new champion to take it forward. This should be the role of the Florentine Academy, directly governed by Cosimo de 'Medici, "one of the great princes of Christendom".[15][3] The role of the Academy, he argued, would be to set out the rules of the language. Every work of medicine, law or theology would then be translated and read in the Florentine idiom. This would effectively make Aristotle a citizen of Florence, with every part of his philosophy faithfully rendered in the city's spoken language.[3]

Commentary on the Poetics

[edit]Salviati began working on a commentary on Aristotle's Poetics in 1566 but it is possible that only the first of the four books was finished, one still kept at the National Central Library in Florence (Ms. II.II .11), for which the imprimatur was requested and granted only ten years later. But a decade after this, Salviati was still said to be working on it; his unpublished papers were bequeathed to Bastiano de 'Rossi for publishing with a dedication to Alfonso II d'Este. The manuscript, mostly not autograph but with author's corrections of the author, is over 600 pages long, and deals with important interpretative questions. An introductory essay discusses the structure, the sections and the lexicon.[8] Salviati's declared intention was to demonstrate the beauty of the Florentine literary tradition and to allow a different reading of the Poetics, by providing, alongside the Greek text, an Italian literal translation, "word by word", a paraphrase and a commentary, which would "smooth the material and untangle the concepts, parsing the words and clarifying them where needed."[3]

Decameron

[edit]Boccaccio's Decameron had been placed on the Index in 1559: in 1564 it was then placed on the list of books which the Church would consider allowing Catholics to read after suitable editing and revision had taken place.[16] The Church then sponsored a number of revised editions which Catholics could be allowed to read. The first of these, in 1573, (known as the "Deputies' edition") produced by Vincenzo Borghini, simply excised entire characters and sections of stories in a most unsatisfactory way.[17] Although the Church authorised the printing of the Deputies' edition in 1793, it soon came to the view that it was not satisfactory after all, and the Deputies' edition was itself placed on the Index.[18] Grand Duke Cosimo then intervened and in 1580, with the Church's sanction, he entrusted the prestigious task of producing a new edition, acceptable to the Inquisition, to Salviati.[16] The version he produced, sometimes known as the "purged" edition (1582), differed much more radically from the source texts than Borghini's;[3] indeed some of Salviati's contemporaries denounced it as "a disfiguration of Boccaccio."[10]

Salviati edited the Decameron in order to bring it into line with Christian morality. In his version, reprehensible characters created by Boccaccio as churchmen were transformed into lay people. He also thoroughly edited and reworked the language of the text. Like his fellow academicians Salviati believed that writing had to follow pronunciation; “one should avoid spellings which [do] not correspond to the way Tuscans speak… Tuscan pronunciation avoids effort and harshness.” Salviati saw the Decameron primarily as an authoritative linguistic reference, so edited it into what he and his associates believed were the ‘proper’ forms.[19]

Salviati examined a number of manuscript versions of the Decameron but relied principally on the Mannelli Codex.[20][21] Not only were there significant linguistic differences between manuscripts, but there were inconsistencies and variations within the Mannelli Codex itself (for example pray=prego/priego; money=denari/danari; without=senza/sanza). Salviati decided for the most part to follow the variations within the Mannelli Codex because of their phonetic authenticity "since it is likely that they are not merely different but arise from the same common form, and we cannot simply prefer one of them". He was less conservative in other aspects of his editing; inserting punctuation, eliminating latinisms (choosing 'astratto' rather than 'abstracto' for 'abstract'), removing the letter 'h' within words ('allora' rather than 'allhora' for 'now'), preferring 'zi' to 'ti' ('notizia' instead of 'notitia') and standardising forms such as 'bacio' rather than 'bascio' (kiss) and 'camicia', not 'camiscia' (shirt). His approach to spelling was in effect a middle way between classical writing and modern speech, without tending towards the radical proposals for a completely new writing system put forward by Gian Giorgio Trissino, Claudio Tolomei and Giorgio Bartoli.[3]

Rules of Tuscan Speech and Remarks on the Decameron

[edit]The Rules of Tuscan Speech (1576–77) was a grammar guide that Salviati wrote for Ercole Cortile, the d'Este ambassador to the Medici court, in the hope that it would smooth his path to an appointment at the court of Ferrara. Although much briefer than the later and more mature Remarks, this work is more comprehensive, dealing with all of the parts of speech, focusing particularly on the verb. Following his teacher Benedetto Varchi, Salviati considered the verb in terms of tense, mood and aspect.[3]

The Remarks on the Decameron takes the new edition of the Decameron as its starting point and deals with many important aspects of the debate around language. It was published in two volumes, the first in Venice (printed by Guerra in 1584) and the second in Florence (Giunti 1586). The first volume is divided into three books, dealing respectively with the philological issues involved in the 1582 edition, the rules of grammar, and pronunciation and spelling.[16] In this volume, dedicated to his protector Jacopo Buoncompagni, Duke of Sora, Salviati set out his main principle: "the rules of our common speech should be taken from our old authors, that is, from those who wrote from the thirteenth century to the fourteenth century: because before this the language had not yet reached the high point of its beautiful florescence, and after this it undoubtedly faded suddenly."[3] The first volume concludes with the text of Decameron I, 9, followed by twelve renditions of the same text in twelve different Italian dialects, in order to show the superiority of Boccaccio's language. One of the twelve versions was in common Florentine speech, attributed to an illiterate person: this version does not vary much from Boccaccio, thus demonstrating the 'natural' primacy of Florentine.[8]

Salviati thought it was necessary to use as many words as possible from fourteenth-century Florentine, but nevertheless to rely on modern speech as a guide for pronunciation (and therefore for the spelling). He adopted a "naturalistic" perspective, which led him to support "popular sovereignty in linguistic use, [...] the priority of speech [i.e. over the written form] in the use of language, [...] linguistic purity as a natural endowment of the Florentine". His hostility to the fifteenth-century tendency towards latinism, which he considered artificial and degrading to the original purity of the language, prompted him to criticize Tasso. The second volume, dedicated to Francesco Panigarola, deals with grammatical questions, in particular of nouns, adjectives, articles and prepositions, in more detail than he had set out in the Rules of Tuscan Speech.[3]

References

[edit]- ^ "Leonardo Salviati (1540–1589)". data.bnf.fr. Bibliothèque nationale de France. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ "Lionardo Salviati e il Primato del Fiorentino". ladante.arte.it. ARTE.it. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Maraschio, Nicoletta. "Salviati, Lionardo". Enciclopedia dell'Italiano. Treccani. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Leonardo Salviati (1565). Orazione funerale di Lionardo Salviati delle lodi di M. Benedetto Varchi. eredi di Lorenzo Torrentino, e Carlo Pettinari. p. 4.

- ^ Minou Schraven (2017-07-05). Festive Funerals in Early Modern Italy: The Art and Culture of Conspicuous Commemoration. Taylor & Francis. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-351-56707-7.

- ^ Leonardo Salviati (1585). Orazione funerale, del caualier Lionardo Saluiati, delle lodi di Pier Vettori, senatore, e ... recitata pubblicamente in Firenze, per ordine della fiorentina accademia, nella chiesa di Santo Spirito, il dì 27 di gennaio, 1585, nel Consolato di Giouambatista di Giouanmaria Deti. Dedicata alla santità di nostro signore, papa Sisto Quinto. per Filippo e Iacopo Giunti. p. 3.

- ^ a b Leonardo Salviati (1810). Opere del cavaliere Lionardo Salviati: Orazioni del cavaliere Lionardo Salviati. dalla Società tipografica de' Classici Italiani, contrada di s. Margherita. p. 269.: 269

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Gigante, Claudio. "SALVIATI, Lionardo". Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani. Treccani. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ The Monthly Magazine: Or, British Register ... 1816. p. 491.

- ^ a b Derek Jones (2001). Censorship: A World Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 257–. ISBN 978-1-136-79864-1.

- ^ a b Tosi, Arturo. "The Accademia della Crusca in Italy: past and present". Accademiadellacrusca.it. Accademia Della Crusca. Retrieved 7 December 2018.

- ^ "L'Accademia Della Crusca". Renaissance Dante in print. University of Notre Dame. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Bartolomeo Gamba (1828). Serie dei testi di lingua italiana e di altri esemplari del bene scrivere opera nuovamente rifatta da Bartolommeo Gamba di Bassano e divisa in due parti . dalla tipografia di Alvisopoli. pp. 182–.

- ^ a b Geekie, Christopher (2018). "'Parole appiastricciate': The Question of Recitation in the Tasso-Ariosto Polemic". Journal of Early Modern Studies. 7: 99–127. doi:10.13128/JEMS-2279-7149-22839. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ a b c Gaetana Marrone; Paolo Puppa (2006-12-26). Encyclopedia of Italian Literary Studies. Routledge. pp. 1668–. ISBN 978-1-135-45530-9.

- ^ a b c Gargiulo, Marco (2009). "Per una nuova edizione Degli Avvertimenti della lingua sopra 'l Decamerone di Leonardo Salviat" (PDF). Heliotropa. 6 (1–2): 15–28. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Cormac Ó Cuilleanáin (1984). Religion and the clergy in Boccaccio's Decameron. Ed. di Storia e Letteratura. pp. 18–19. GGKEY:AXJH4Z9WQFW.

- ^ Rizzo, Alberto. "La Censura". ilsegretodeldecamerone.com. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Small, Brendan Michael. "Chapter Fifteen The Language Question: Cultural Politics of the Medici Dynasty". Homer Among the Moderns. Pressbooks.com. Retrieved 23 November 2018.

- ^ Clarke, K.P. (2017). "Author-Text-Reader: Boccaccio's Decameron in 1384" (PDF). Heliotropia. 14: 101. Retrieved 8 December 2018.

- ^ Maino, Paolo (2012). "L'uso dei testimoni del Decameron nella rassettatura di Lionardo Salviati". Aevum. 86: 1005–. Retrieved 8 December 2018.