Lin Shuangwen rebellion

| Pacification of Taiwan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

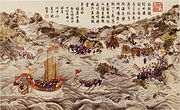

The Qing fleet returning from Taiwan | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| Taiwanese rebels | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Lin Shuangwen Zhuang Datian (POW) Lin Da | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

3,000 police 10,000 troops sent to relieve Taiwan in 1786 20,000 troops brought by Fuk'anggan in 1788 including Green Standard Army and Eight Banners Quanzhou militia Hakka militia a minority of Zhangzhou militia | Zhangzhou militia (Minority of Quanzhou militia) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Unknown | Unknown | ||||||

The Lin Shuangwen rebellion (Chinese: 林爽文事件; Pe̍h-ōe-jī: Lîm Sóng-bûn sū-kiāⁿ; lit. 'Lin Shuangwen Incident') occurred in 1787–1788 in Taiwan under the rule of the Qing dynasty. The rebellion was started by the rebel Lin Shuangwen and was pacified by the Qianlong Emperor. Lin Shuangwen was then executed.[1]

It started when the Qing Taiwan governor Sun Jingsui (孙景燧) outlawed the Tiandihui society and arrested Lin Shuangwen's uncles. Lin then murdered Sun and formed an army to resist. Lin's forces which were mostly Zhangzhou people attacked several Taiwan sites, and fought militias mostly made out of Quanzhou and Hakka people, however some Quanzhou fought on Lin's side and some Zhangzhou people were on the Qing side. The Qing sent troops to quell the rebellion and execute Lin and the rebels.[2]

Events

[edit]Predecessors

[edit]Zhangzhou militias under Zhu Yigui rebelled against the Qing in 1721 and fought against militias mostly composed of Quanzhou and Hakka people.

Start of rebellion

[edit]Lin was an immigrant from Zhangzhou who came to Taiwan with his relatives in the 1770s. They were involved in the secret anti-Qing Tiandihui (Heaven and Earth Society). Internecine fighting between Zhangzhou, Quanzhou and Hakka plagued the island.

In 1786, the Qing-appointed Governor of Taiwan, Sun Jingsui, discovered and suppressed the Tiandihui. He also arrested Lin Shuangwen's uncles. The Tiandihui members gathered Ming loyalists, and Lin Shuangwen, Zhuang Datian and other leaders organized the rest of the society members in a revolt in an attempt to free his uncle.

On January 16, 1787, Lin murdered Sun Jingsui and other officials. The number of insurgents quickly rose to 50,000 people. By February, in less than a year, the rebels occupied almost all of southern Taiwan except for Zhuluo County and Lugangzhen (鹿港镇). They managed to push out some government forces out of Lin's home base in Changhua and Tamsui.

In response, Qing troops were sent to suppress them in a hurry. The eastern insurgents defeated the poorly organized troops and had to resist falling to the enemy. However, Lin's Zhangzhou forces fought against militias made out of mostly Quanzhou and Hakka people - who together made up approximately half of the Han migrants to Taiwan, with Lin's Zhangzhou people comprising the other half. Militias made out of majority Quanzhou and Hakka people cooperated with the Qing army to defeat Lin's armies.[3][4][5][6][7]

The Tiandihui rebels under Lin Shuangwen performed rituals like cockerel sacrifice.[8]

Quanzhou and Hakka

[edit]By this point, the fighting was drawing in Zhangzhou people beyond just the society members, and activating the old feuds; this brought out Quanzhou networks (as well as Hakka) on behalf of the government. Lin's forces were made mostly of Zhangzhou people, and the Zhangzhou and Quanzhou people were already feuding with each other, so the rebellion sparked a large-scale battle between the two sides. The Quanzhou faction formed their own army and cooperated with the Qing forces to resist Lin.

Zhangzhou militias also fought against Hakka militias. Hakka people from Taozhumiao (桃竹苗), Liudui (六堆), and other places organized a Taiwan Hakka volunteer army. The Hakka cooperated with the Qing army to defeat Lin's forces and defend their homes. Under the leadership of Chen Ziyun (陳紫雲), the Qing and Hakka forces battled in Hsinchu and other places.

Eventually, the government sent sufficient force to restore order. The governors of Zhejiang and Fujian then sent Fuzhou general Hengrui (恆瑞) and 4,000 troops to Taiwan to help quell the rebellion. After April 23, another 10,000 Qing troops were sent to Taiwan, and then another 7,000 were added.[3][4][5][6][7]

Qing reinforcements

[edit]Finally, in December 10, the Qing imperial court sent Fuk'anggan to quell the rebellion with a force of 20,000 soldiers, while Hailancha, Counsellor of the Police, deployed nearly 3,000 people to fight the insurgents with the majority from the Green Standard Army and a minority from the Eight Banners. These new troops were well equipped, disciplined and had combat experience which proved enough to route the insurgents.

The Qing annihilated Lin's army and captured Lin on February 10, 1788. As many as 300,000 took part in the rebellion. The Ming loyalists had lost the war, their leaders were executed, and the remaining rebels hid among the locals.[3][4][5][6][7]

Punishment

[edit]Lin Shuangwen was executed, and the Heaven and Earth Society was dispersed to mainland China or sent into hiding. Other criminals and rebels were sentenced to death by Lingchi (a method of torture). The tombs of their ancestors were excavated. The female relatives of the rebel leaders (daughters, wives, concubines) were sentenced to penal transportation and were sent to the northeastern frontier in Ningguta in Heilongjiang to become slaves of the Solon. Sons of rebel leaders above 15 were beheaded. The Qianlong emperor and Heshen ordered that sons of rebel leaders under the age of 15 to be taken to Beijing and castrated by the Imperial Household Department to work as eunuch slaves in the Yuanmingyuan (Summer Palace).[9][10][11] The boys who were castrated were aged 4 to 15 years old and 40 of them were named on one memorial. This new policy of castrating sons of killers of 3 or more people and rebels helped solve the supply of young eunuchs for the Qing Summer Palace.[12] The Qing were willing to lower their normal age limit for castration all the way to 4 when using castration as punishment for sons of rebels when it normally wanted eunuchs castrated after 9.[13] Other times, the Qing Imperial Household Department waited until the boys reached 11 years old before castrating them, like when they waited for the 2 young imprisoned sons of executed murderer Sui Bilong from Shandong to grow up. The Imperial Household Department immediately castrated the 11 year old Hunanese boy Fang Mingzai to become a eunuch slave in the Qing palace after his father was executed for murder.[12] The Qing Summer palace, due to this policy of castrating sons of mass murderers and rebels received many young healthy eunuchs.[12] 130 sons of rebels 15 and younger were taken into custody by the Qing. The rebel leader Zhuang Datian's 4-year-old grandson Zhuang Amo was one of those castrated. There was another Lin family who joined the Lin Shuangwen rebellion. Lin Da was ordered to lead 100 people by Lin Shuangwen and given the title "general Xuanlue". Lin Da was 42 when he was executed by Lingchi. He had 6 sons, the 2 older ones died before and his 3rd son Lin Dou died from sickness before he could be castrated in Beijing while hi's fourth and fifth sons were castrated, the 11 year old Lin Biao and 8 year old Lin Xian. However his 6th and youngest son, 7 year old Lin Mading was given away to a relative (uncle) named Lin Qin for adoption, and Lin Qin remained on the Qing side and joined a pro-Qing "righteous" militia and did not join the rebellion so Lin Mading was not castrated. Lin Mading had 2 children after marrying his wife in 1800 when he was 20.[14][15]

Imposing a penalty of castration upon the sons of rebels and murderers of 3 or more people was part of a new Qing policy to ensure a supply of young boy eunuchs since the Qianlong emperor ordered young eunuchs to be shifted towards the main imperial residence in the Summer Palace. Norman A. Kutcher connected the Qing policy on obtaining young eunuchs to the observation that young boy eunuchs were prized by female members of the Qing Imperial family as attendants, noted by the British George Carter Stent in the 19th century.[16][17] Norman Kutcher noted that George Stent said young eunuchs were physically attractive and were used for "impossible to describe" duties by female imperial family members and they were considered "completely pure". Kutcher suggests the boys were used for sexual pleasure by Qing imperial women, connecting them to the boy eunuchs called "earrings" who were used for that purpose.[12]

Sons of murderers above 15 were not beheaded unlike sons and grandsons of rebels and instead they were also castrated as eunuchs in the palace. The wives and daughters of murderers would be given to the murder victims' relatives if they still lived unlike wives and daughters of rebels. Qianlong and the Imperial Household Department under Heshen later decreed that sons of murderers who were 16 years old and older would be exiled as slaves to become slaves of the Solon on the frontier in Ningguta in Heilongjiang or Ili in Xinjiang after castration while the sons 15 and younger would be kept as eunuchs in the Imperial palace since the younger sons could be controlled while the older sons were uncontrollable in a decision made in 1793.[18]

Lin Shuangwen had some relatives like Lin Shi (Lin Shih) who founded the Wufeng Lin clan in Taiwan and did not take part in the uprising but instead hid out in a Qing loyalist town, Lukang, Changhua. He was briefly imprisoned[19][20][21] and 400 jia (chia) of farmland was seized by the state from Lin Shi as punishment for being related to a rebel but he relocated to Wufeng and his son Lin Jiayin (Lin Chia-yin) (1782-1839) regrew the family fortune. Lin Shi's great grandson Lin Wencha (Lin Wen-ch'a) (1828-1864) help the Qing dynasty crush the Hakka Taiping rebels Zhejiang and Fujian provinces.[22][23][24]

Zhuang Datian had enlisted Taiwan Plains Aboriginal female shaman Jin Niang to support Lin Shuangwen during the rebellion[25] She healed Zhuang Datian's son.[26] She was taken to Beijing to be executed by lingchi as well.[27][28] A novel was written about her later by Lin Jyan-long[29]

During Qianlong's reign, Li Shiyao was involved in graft and embezzlement. Li Shiyao was demoted of his noble title and sentenced to death. However, after assisting in quelling the Lin Shuangwen rebellion, his life was spared.[4]

Aftermath

[edit]After the rebellion, local feuds between the Zhangzhou, Quanzhou, and Hakka people appeared only sporadically through the early 19th century, coming to an end in the 1860s. However, they never again were serious to push out the government or encompass the whole island. There were more than a hundred rebellions during the early Qing. The frequency of rebellions, riots, and civil strife in Qing Taiwan is evoked by the common saying "every three years an uprising; every five years a rebellion" (三年一反、五年一亂).[30]

In total, the Qing deployed fewer than 40,000 troops, and it took over one year to stamp the rebellion. However, through clever use of ethnic relations, forming good relations with the aborigines, and taking advantage of the feuds between the Taiwan internal factions (the Zhangzhou, Quanzhou migrants), the Qing successfully annihilated Lin's family and forces. In 1787, the Qianlong Emperor changed the name of Zhuluo County to Jiayi County (嘉義縣) to reward the Zhuluo people in helping resist and defeat Lin Shuangwen.[3][4][5][6][7]

Gallery

[edit]-

Battle of Dabulin

-

Attack on Douliumen (Zhuluo)

-

Conquest of Douliumen (Zhuluo)

-

Conquest of Dali

-

Attack on the mountain Xiaobantian

-

Battle of Kuzhai

-

Capture of the rebel chief Lin Shuangwen

-

Battle of Jijipu

-

Battle of Dawujing

-

Capture of Zhuang Datian

-

Crossing the ocean and triumphant return

-

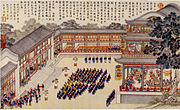

Victory banquet of the emperor to greet the officers who attended the campaign against Taiwan.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Peterson, Willard J. (2002), Part 1: The Ch'ing Empire to 1800, The Cambridge History of China, vol. 9, Cambridge University Press, p. 269, ISBN 9780521243346, OL 7734135M

- ^ "Qianlong Battle Prints" (PDF). Battle of Qurman - Painting from 1760 - Lost Fragment from ...

- ^ a b c d Evelyn S. Rawski (15 November 1998). The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions. University of California Press. pp. 72–. ISBN 978-0-520-92679-0.

- ^ a b c d e Hummel, Arthur W. Sr., ed. (1943). . Eminent Chinese of the Ch'ing Period. United States Government Printing Office.

- ^ a b c d "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-08-11. Retrieved 2016-07-02.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ a b c d "李永芳将军的简介 李永芳的后代-历史趣闻网". Archived from the original on 2017-12-03. Retrieved 2016-07-02.

- ^ a b c d "曹德全:首个投降后金的明将李永芳_[历史人物]_抚顺七千年-Wap版". Archived from the original on 2016-10-07. Retrieved 2016-06-30.

- ^ Katz, Paul R. (2008). Divine Justice: Religion And The Development Of Chinese Legal Culture. Academia Sinica on East Asia (illustrated ed.). Routledge. p. 75. ISBN 978-1134067879.

- ^ 莊吉發 (1992年). "《清代臺灣秘密會黨的發展與社會控制》" (PDF). 《人文及社會科學集刊》. 第5卷 (第1期). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-02-23. Retrieved 2020-07-23.

- ^ Chuang Chi-fa., Chi-fa (2002). "Reviewed work: Brotherhoods and Secret Societies in Early and Mid-Qing China. The Formation of a Tradition, David Ownby". T'oung Pao. 88 (1/3). Brill: 196. JSTOR 4528897.

- ^ "QIANLONG BATTLE PRINTS" (PDF). Battle of Qurman - Painting from 1760 - Lost Fragment from ...

- ^ a b c d Kutcher, Norman A. (2018). Eunuch and Emperor in the Great Age of Qing Rule (reprint ed.). Univ of California Press. p. 169. ISBN 978-0520969841.

- ^ Dale, Melissa S. (2018). Inside the World of the Eunuch: A Social History of the Emperor's Servants in Qing China (illustrated, reprint ed.). Hong Kong University Press. pp. 34, 35. ISBN 978-9888455751.

- ^ 陈, 孔立. "1815 年台湾籍太监林表之死" (PDF). 25 周年学术研讨会论文. 厦门大学台湾研究院: 1, 2.

- ^ 林, 育德 (2014-06-05). 一個臺灣太監之死:清代男童集體閹割事件簿. 啟動文化.

- ^ Kutcher, Norman A. (2010). "Unspoken Collusions: The Empowerment of Yuanming Yuan Eunuchs in the Qianlong Period". Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies. 70 (2). Harvard-Yenching Institute: 472, 473. doi:10.1353/jas.2010.0012. JSTOR 40930907. S2CID 159183602.

- ^ 柯, 启玄 (2017-02-22). "乾隆朝太监的短缺及其影响". 中国人民大学清史研究所. Archived from the original on 2019-06-22.

- ^ MacCormack, Geoffrey (1996). The Spirit of Traditional Chinese Law. Spirit of the laws. University of Georgia Press. p. 207. ISBN 0-8203-1722-5.

- ^ Meskill, Johanna Margarete Menzel (2017). A Chinese Pioneer Family: The Lins of Wu-feng, Taiwan, 1729-1895. Studies of the East Asian Institute. Vol. 4941 of Princeton Legacy Library. Princeton University Press. pp. 66, 60. ISBN 978-1400886418.

- ^ Free China Review. 1983. p. 26.

The family pioneer , Lin Shih , settled in Changhua County . It was his son , Lin Chia - yin , who led the Lins to the estate's current site . The residence was later divided , and family members were quartered in an Upper House and a ...

- ^ Digest of Chinese Studies. Contributors American Association for Chinese Studies, Han xue yan jiu zhong xin. American Association for Chinese Studies. 1986. p. 25.

Due to the wealth of material he discovered , Mr. Huang finds that an exploration of the Lin family gives a microscopic ... yin , Lin Shih's grandson , re - established his family's enterprise , built up the family fortune , and laid a ...

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Rubinstein, Murray A. (2007). Rubinstein, Murray A. (ed.). Taiwan: A New History. An East Gate book, Taiwan in the modern world (illustrated ed.). M.E. Sharpe. pp. 155, 156, 157. ISBN 978-0765614940.

- ^ Rubinstein, Murray A. (2015). Taiwan: A New History: A New History (2, illustrated, revised ed.). Routledge. pp. 155, 156, 157. ISBN 978-1317459088.

- ^ Han Cheung (15 May 2022). "Taiwan in Time: From village strongman to imperial commander". Taipei Times. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ^ Ownby, David; Heidhues, Mary F. Somers (2016). Secret Societies Reconsidered: Perspectives on the Social History of Early Modern South China and Southeast Asia: Perspectives on the Social History of Early Modern South China and Southeast Asia (illustrated, reprint ed.). Routledge. p. 55. ISBN 978-1315288031.

- ^ Haar, Barend ter (2021). Ritual and Mythology of the Chinese Triads: Creating an Identity. BRILL. p. 286. ISBN 978-9004483040.

- ^ Tu, Hsiao-Mei (2018). "〈舟車何遙遙──從平埔族人金娘一案觀解京之路〉A Long Journey: Investigating the Road to Capital by Reviewing the Case of Taiwanese Plains Indigenous Person Jin Niang". 故宮文物月刊.

- ^ 方, 格子 (2021-08-31). "台灣第一位女軍師是她!通曉方術、統領萬名反清勇士…揭歷史課本不提的抗清女英雄". 風傳媒.

- ^ Wang, I-Chun (2018). "CHAPTER 3 Cultural Encounters and Imagining Multicultural Identitites in Two Taiwanese Historical Novels". In Wong, Jane Yeang Chui (ed.). Asia and the Historical Imagination. Springer. p. 53. ISBN 978-9811074011.

- ^ Skoggard, Ian A. (1996). The Indigenous Dynamic in Taiwan's Postwar Development: The Religious and Historical Roots of Entrepreneurship. M.E. Sharpe. ISBN 9781563248467. OL 979742M. p. 10