Ligue de la patrie française

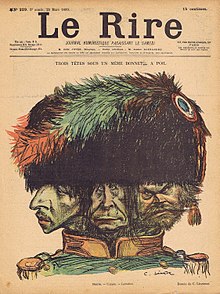

1899 caricature by Charles Lucien Léandre depicting Barrès, Coppée and Lemaître as the three heads of the League | |

| Formation | December 1898 |

|---|---|

| Dissolved | 1909 |

| Type | Political organization |

| Legal status | Defunct |

| Purpose | Patriotism, anti-Dreyfus |

Region | France |

Membership (1902) | 40,000 |

Official language | French |

President | Jules Lemaître |

The Ligue de la patrie française (French Homeland League) was a French nationalist and anti-Dreyfus organization. It was officially founded in 1899, and brought together leading right-wing artists, scientists and intellectuals. The league fielded candidates in the 1902 national elections, but was relatively unsuccessful. After this it gradually became dormant. Its bulletin ceased publication in 1909.

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

The League originated with three young academics, Louis Dausset, Gabriel Syveton and Henri Vaugeois, who wanted to show that Dreyfusism was not accepted by all at the University. They were opposed to the League for the Rights of Man and wanted to show that not all intellectuals supported the Left, and the cause of the homeland was as valid as the cause of Dreyfus and the lay Republic.[1]

After an initial meeting on 25 October 1898 in Paris a section was quickly opened in Lille.[2] They launched a petition that attacked journalist and novelist Émile Zola and what many saw as an internationalist, pacifist left-wing conspiracy.[3] In November 1898 their petition gained signatures in the Parisian schools, and was soon circulated throughout political, intellectual and artistic circles in Paris.[1]

Charles Maurras gained the interest of the writer Maurice Barrès, and the movement gained the support of three eminent personalities: the geographer Marcel Dubois, the poet François Coppée and the critic and literature professor Jules Lemaître.[1] Barrès would provide the inspiration while Lemaitre looked after the organization.[3] Charles Daniélou had been present at the last meeting between Zola and François Coppée during the Dreyfus affair. Zola had decided to publish his article J'accuse…!, in which he proclaimed that Dreyfus was innocent, despite pleas by Coppée. Daniélou sided with Coppée and helped found the League in December 1898.[4] The final decision to create the League was made on 31 December 1898.[1]

Active period

[edit]

The Ligue de la patrie française was established on 4 January 1899 with Jules Lemaître as its nominal leader.[5] Lemaître held the organizational meeting on 19 January 1899.[6] Maurice Barrès was in practice the intellectual leader.[7] The League was aligned with the Académie française, the army, the church, the aristocracy and the wealthy classes.[8] It brought together a large number of antidreyfusard intellectuals to show that the great names of letters and science did not support revision of the verdict of the Dreyfus trial.

This conservative group had prestige comparable to that of the signatories of the Manifeste des intellectuels launched by Georges Clemenceau.[5] Many well-known members of the Académie signed on including Léon Daudet, Albert Sorel and Jules Verne. The painters Edgar Degas and Pierre-Auguste Renoir supported the movement. About 30,000 members joined in the first month.[3] Workers, artisans and employees represented at most 4% of the membership, while members of the literary, artistic, legal and medical professions made up almost 70%.[9]

The League did not at first take an anti-Semitic position, although Lemaitre claimed at the January organizational meeting that for the past twenty years Jews, Protestants and Freemasons had conspired to run France.[3] The League refused to engage in a resolute defense of the church. The League was interested in restoring order, but not in establishing an authoritarian regime.[9] Unlike the Ligue des Patriotes and other populist leagues, with Lemaître as president the Ligue de la patrie française rejected violence and avoided abusive language, and thus was more acceptable to the middle classes.[6]

By February 1899 the league claimed 40,000 members.[6] However, despite being well-funded and represented throughout France the organization was weak.[6] The League was divided between Republican moderates like Ferdinand Brunetière who just wanted to end the disruption caused by the Dreyfus affair and anti-Semitic nationalists like Barrès who wanted an excuse to overthrow the Republic.[3] François Coppée had Bonapartist leanings and was in favor of a coup.[10]

In 1899 Maurice Pujo and Henri Vaugeois left the League and established a new movement, Action Française, and a new journal, Revue de l'Action française.[11] Charles Maurras soon joined the Action Française, whose leaders criticized the timid nature of the League and its lack of clear objectives. The Revue de l'Action française expressed more radical views, and was anti-Republican.[12] Maurras thought the Bourbon monarchy should be restored, using violence if needed.[13]

The League had some success in the Paris municipal elections in 1900, but soon began to fall apart. Antidreyfusism proved not to be a sufficiently strong cause to hold together members who had radically different opinions on other subjects.[14] The League's candidates in the 1902 legislative elections did poorly outside of Paris.[6] Most of the League's activists abandoned it in favor of Albert Gauthier de Clagny's[a] Républicains plébiscitaires or Jules Méline's Fédération républicaine.[16] The League's treasurer Gabriel Syveton was elected deputy for the Seine in 1902.[16] A meeting organized on 7 March 1903 in Lille by the League and the Ligue des Patriotes was able to draw 5,000 people including students, young Catholics, clerics and reactionary notables.[2] However, the movement went into rapid decline after being defeated in the 1904 municipal elections.[10]

Later years

[edit]

General Louis André, the militantly anticlerical War Minister from 1900 to 1904, used reports by Freemasons to build a huge card index on public officials that detailed those who were Catholic and attended Mass, with a view to preventing their promotions.[17] In 1904, Jean Bidegain, assistant Secretary of Grand Orient de France, sold a selection of the files to Gabriel Syveton for 40,000 francs.[18]

In November 1904 Syveton gained notoriety when he physically attacked General André in the Assembly in a debate over the files.[16] Syveton died on 9 December 1904 the day before he was due to appear before the Court of Assizes. The nationalists claimed that he had not committed suicide but had been assassinated by the Masons.[16] The Affaire Des Fiches scandal led directly to the resignation of prime minister Émile Combes.[18]

After Lemaitre left the League, Louis Dausset assumed the presidency. He in turn resigned in 1905.[16] The Bulletin officiel de la Ligue de la Patrie française appears to have ceased publication in 1909.[19]

Executive

[edit]The executive of the league included:[20]

- François Coppée – Honorary President

- Jules Lemaître – President

- Gabriel Syveton – Treasurer

- Louis Dausset – Secretary general

- Henri Vaugeois – Assistant secretary

- Alfred Mathieu Giard – Delegate

- François de Mahy – Delegate

- Maurice Barrès – Delegate

- Ferdinand Brunetière – Delegate

- Marcel Dubois – Delegate

Members

[edit]The first members of the league also included:[20]

- Juliette Adam

- Paul Allard

- Gaston Audiffret-Pasquier

- Ernest Babelon

- Charles Barbier de Meynard

- Arvède Barine

- Albert Bartholomé

- Charles Costa de Beauregard

- André Bellessort

- Jean Béraud

- Jacques-Émile Blanche

- Marie-Louis-Antoine-Gaston Boissier

- Robert de Bonnières

- Henri de Bornier

- Théodore Botrel

- Paul Bourget

- Joseph Valentin Boussinesq

- Henri Boutet

- Pierre de Bréville

- Albert, 4th duc de Broglie

- Charles Jules Edmée Brongniart

- Caran d'Ache

- Carolus-Duran

- Albert Carré

- Godefroy Cavaignac

- Honoré Champion

- Anatole Chauffard

- Victor Cherbuliez

- Arthur Chuquet

- Édouard Collignon

- Gustave-Claude-Etienne Courtois

- Pascal Dagnan-Bouveret

- Léon Daudet

- Edgar Degas

- Léon Deschamps

- Édouard Detaille

- Léon Dierx

- Jules-Albert de Dion

- René Doumic

- Guillaume Dubufe

- Pierre Duhem

- Emmanuel des Essarts

- Émile Faguet

- Jean-Louis Forain

- Paul Foucart

- Henry Gauthier-Villars

- Émile Gebhart

- Jean-Léon Gérôme

- Georges Goyau

- Alfred Grandidier

- Maurice Hauriou

- José-Maria de Heredia

- Charles Hermite

- Henry Houssaye

- Henri Huchard

- Vincent d'Indy

- Jean Antoine Injalbert

- Ernest de Jonquières

- Camille Jordan

- Pierre Laffitte

- Albert Auguste Cochon de Lapparent

- Henri Lavedan

- Henry Louis Le Châtelier

- Jean-Jules-Antoine Lecomte du Nouÿ

- Louis Léger

- Ernest Legouvé

- Émile Lemoine

- Auguste Longnon

- Pierre Louÿs

- Frédéric Masson

- Charles Maurras

- Stanislas-Étienne Meunier

- Alfred Mézières

- Frédéric Mistral

- Parfait-Louis Monteil

- Georges Montorgueil

- Adrien Albert Marie de Mun

- Jacques Normand

- Philbert Maurice d'Ocagne

- Edmond Perrier

- Louis Petit de Julleville

- Émile Picard

- Maurice Pujo

- Jean-François Raffaëlli

- Alfred Nicolas Rambaud

- Onésime Reclus

- Sibylle Riqueti de Mirabeau

- Henri Rouart

- Eugène Rouché

- Edmond Rousse

- René de Saint-Marceaux

- Francisque Sarcey

- Pierre de Ségur

- Paul Armand Silvestre

- Albert Sorel

- André Theuriet

- Georges Thiébaud

- Paul Thureau-Dangin

- Suzanne Valadon

- Albert Vandal

- Jules Verne

- Melchior de Vogüé

- Eugène-Melchior de Vogüé

- Charles Wolf

Publications

[edit]Journals

[edit]- Almanach de la Patrie Française (in French), Paris, 1900–1901, ISSN 2417-9949

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) – archives - La Grand'garde (in French), Lille, 1901, ISSN 2128-9565

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - Annales de la Patrie Française (in French), Paris, 1900–1905, ISSN 1149-4190

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link) - Bulletin Officiel de la Ligue de la Patrie Française (in French), Paris, 1905–1909, ISSN 1149-4220

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: untitled periodical (link)

Miscellaneous

[edit]- Barrès, Maurice (1899), Ligue de la patrie française (ed.), La terre et les morts sur quelles réalités fonder la conscience française (in French), Paris: bureaux de "La Patrie française", p. 36

- Ligue de la patrie française (1900), Société anonyme des annales de la patrie française... Statuts (in French), Paris: impr. Maulde : Doumenc, p. 20

- Barrès, Maurice (1900), Ligue de la patrie française (ed.), L'Alsace et la Lorraine (in French), Paris: bureaux de "La Patrie française", p. 34

- Lemaître, Jules (1900), Ligue de la patrie française (ed.), Ligue de la "Patrie française" Discours de M. Jules Lemaître à Grenoble (in French), Angers: impr. de Germain et G. Grassin

- Lemaître, Jules (1900), Ligue de la patrie française (ed.), L'action républicaine et sociale de la Patrie française: discours prononcé à Grenoble le 23 décembre 1900 (in French), Paris: bureaux de "la Patrie française", p. 45

- Bernard, Charles; Cavaignac, Godefroy; Lemaître, Jules; Mercier, Auguste (1902), Ligue de la patrie française (ed.), Conférence de M. Jules Lemaître,... Nancy, 1er décembre 1901 (in French), Nancy: A. Crépin-Leblond, p. 62

- Ligue de la patrie française (1903), Fédération des comités de la "Patrie française", de la Ligue des patriotes, Républicain-nationaliste et Républicain-socialiste français de la 2e circonscription du lve arrondissement de Paris. La Candidature Maurice Barrès (in French), Paris: la Fédération, p. 64

- Barrès, Maurice (1907), Ligue de la patrie française (ed.), Les mauvais instituteurs: conférence prononcée à Paris, le 16 mars 1907 à la grande réunion de la Salle Wagram (in French), Paris: bureaux de "La Patrie française", p. 32

References

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d Pierrard 1998, p. 180.

- ^ a b Condette 1999, p. 209.

- ^ a b c d e Conner 2014, p. 160.

- ^ Gourlay 1996, p. 102.

- ^ a b Sternhell 1972, p. 338.

- ^ a b c d e Ligue de la patrie française – Larousse.

- ^ Pierrard 1998, p. 121.

- ^ Sternhell 1972, p. 274.

- ^ a b d'Appollonia 1998, p. 136.

- ^ a b Tombs 2003, p. 143.

- ^ Rémond 2006, p. 8.

- ^ d'Appollonia 1998, p. 145.

- ^ d'Appollonia 1998, p. 151.

- ^ Pierrard 1998, p. 181.

- ^ Jolly 1960–1977.

- ^ a b c d e d'Appollonia 1998, p. 138.

- ^ Franklin 2006, p. 9.

- ^ a b Read 2012, pp. 339–340.

- ^ Bulletin officiel de la Ligue ... BnF.

- ^ a b Lemaître 1900.

Sources

[edit]- Bulletin officiel de la Ligue de la Patrie française (in French), BnF, retrieved 2016-03-07

- Condette, Jean-François (1999-01-01), La Faculté des lettres de Lille de 1887 à 1945: Une faculté dans l'histoire, Presses Univ. Septentrion, ISBN 978-2-85939-592-6, retrieved 2016-03-07

- Conner, Tom (2014-04-24), The Dreyfus Affair and the Rise of the French Public Intellectual, McFarland, ISBN 978-0-7864-7862-0, retrieved 2016-03-08

- d'Appollonia, Ariane Chebel (1998-12-01), L'extrême-droite en France: De Maurras à Le Pen, Editions Complexe, ISBN 978-2-87027-764-5, retrieved 2016-03-08

- Franklin, James (2006), "Freemasonry in Europe", Catholic Values and Australian Realities, Connor Court Publishing Pty Ltd, ISBN 9780975801543

- Gourlay, Patrick (1996). "Charles Daniélou (1878–1958). La brillante et atypique carrière d'un Finistérien sous la Troisième République" (PDF). Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l'Ouest (in French). 103 (4): 99–121. doi:10.3406/abpo.1996.3888. Retrieved 2015-11-12.

- Jolly, Jean (1960–1977), "Albert GAUTHIER DE CLAGNY", Dictionnaire des parlementaires français de 1889 à 1940 (in French), ISBN 2-1100-1998-0, retrieved 2016-03-08

- Lemaître, Jules (1900), Ligue de la patrie française (ed.), L'action républicaine et sociale de la Patrie française : discours prononcé à Grenoble le 23 décembre 1900 par Jules Lemaître (in French), Paris: bureaux de "la Patrie française", retrieved 2016-03-07

- "Ligue de la patrie française", Dictionnaire de l'Histoire de France (in French), Éditions Larousse, 2005, retrieved 2016-03-07

- Pierrard, Pierre (1998), Les Chrétiens et l'affaire Dreyfus, Editions de l'Atelier, ISBN 978-2-7082-3390-4, retrieved 2016-03-07

- Read, Piers Paul (2012), The Dreyfus Affair: The Scandal that Tore France in Two, Bloomsbury Press

- Rémond, René (2006), "Action française", in Lawrence D. Kritzman (ed.), The Columbia History of Twentieth-Century French Thought, New York: Columbia University Press, ISBN 978-0-231-10790-7

- Sternhell, Zeev (1972), Maurice Barrès et le nationalisme français, Editions Complexe, ISBN 978-2-87027-164-3, retrieved 2016-03-07

- Tombs, Robert (2003-09-02), Nationhood and Nationalism in France: From Boulangism to the Great War 1889-1918, Routledge, ISBN 978-1-134-99796-1, retrieved 2016-03-08