Light chain deposition disease

| Light chain deposition disease | |

|---|---|

| Other names | LCDD |

| |

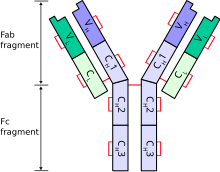

| Schematic diagram of a typical antibody showing two Ig heavy chains (blue) linked by disulfide bonds to two Ig light chains (green). The constant (C) and variable (V) domains are shown. | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Light chain deposition disease (LCDD) is a rare blood cell disease which is characterized by deposition of fragments of infection-fighting immunoglobulins, called light chains (LCs), in the body. LCs are normally cleared by the kidneys, but in LCDD, these light chain deposits damage organs and cause disease. The kidneys are almost always affected and this often leads to kidney failure. About half of people with light chain deposition disease also have a plasma cell dyscrasia, a spectrum of diseases that includes multiple myeloma, Waldenström's macroglobulinemia, and the monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance premalignant stages of these two diseases.[1][2] Unlike in AL amyloidosis, in which light chains are laid down in characteristic amyloid deposits, in LCDD, light chains are deposited in non-amyloid granules.[3]

Signs and symptoms

[edit]Light chain deposition disease can affect any organ.[3] Renal involvement is always present and can be identified by microscopic hematuria and proteinuria. Due to the gradual buildup of light chains from plasma filtration, renal function rapidly declines in the majority of patients with LCDD as either acute tubulointerstitial nephritis or rapidly progressing glomerulonephritis. This condition can include nephrotic syndrome, proteinuria, and/or renal failure.[4] Regardless of the degree of light chain excretion, renal failure happens with a comparable frequency. Furthermore, hypertension may be present at the time of diagnosis in patients with LCDD.[5] Deposits may form in the skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract, thyroid glands, pancreas, bone marrow, spleen, lymph nodes, and adrenal glands.[3] Extrarenal deposition with symptoms is uncommon. It is unclear if localized LCDD is a real condition or if it is the first sign of a silent systemic LCDD.[6]

The liver is the most common extra-renal site in LCDD, although involvement is not always limited to this organ. There appears to be no relationship between the degree of light chain deposition within the liver and the severity of liver dysfunction.[7] In addition to portal hypertension and hepatic insufficiency, affected patients may die from hepatic failure.[8]

Cardiac involvement may be linked to paroxysmal atrial fibrillation,[9] severe congestive heart failure, and restrictive cardiomyopathy.[10]

The lungs are rarely affected by light chain deposition disease, which typically damages the parenchyma;[11] bronchial involvement seems to be extremely uncommon.[12] However recent reports have indicated that the major airways are involved. There have been descriptions of nodular as well as diffuse pulmonary interstitial diseases; however, the literature has only reported seven occurrences of pulmonary nodular-type LCDD to date.[13]

The effects of systemic protein deposition on the nerves are comparable to those of amyloidosis, which is clinically characterized by polyneuropathy.[14] Deposits may form in the choroid plexus and along nerve fibers.[15] Additionally, isolated LCDD within the brain has been reported.[16]

Cause

[edit]LCDD develops as a result of overproduction and thus deposition of abnormal immunoglobulins. About 60% of cases develop in the context of plasmacytoma, multiple myeloma, and other lymphoproliferative disorders. However, in many cases, an underlying cause cannot be identified.[4]

Mechanism

[edit]The main light chain structure in LCDD presumably dictates how the disease manifests in the body. Though κI-IV has been described,[17] the sequenced kappa light chains in LCDD are more likely to belong to the V-region subtype, of which VκIV appears to be overrepresented.[18] The pathogenicity of these proteins has not been linked to any particular structural pattern or residue, but a number of recurring characteristics have been identified.[19] Firstly, somatic mutations, not germline mutations, are the source of the amino acid substitutions. Secondly, the region that determines complementarity is where substitutions happen most frequently.[17] Third, hydrophobic residues are more likely to be introduced by the mutations reported in both the kappa and light chains.[20] This could disrupt protein-protein interactions and destabilize the protein, leading to protein deposition in tissues.[21] The propensity for aggregation is exemplified in a murine model of LCDD where light chain deposition was observed in the kidney of transfected mice using vectors that contained kappa light chain sequence from an individual with LCDD with the VκIV subtype.[22] Lastly, because some patients with LCDD have isolates of kappa light chains with mutations that produce new N-glycosylation sites, posttranslational modification can be linked to the creation of pathologic light chains.[23] It is possible that the new hydrophobic residues along with N-glycosylation sites will make it more likely for the light chains to accumulate in the affected tissues' basement membranes.[24] The mesangial cell is also thought to play a role in the pathogenesis of LCDD.[25]

Diagnosis

[edit]A number of laboratory tests are required in order to assist in diagnosing LCDD. Blood and urine samples are collected for evaluation of kidney and liver function and determination of the presence of a monoclonal protein. Imaging studies such as echocardiography and an ultrasound of the abdomen will be performed. A CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography (PET) may also be indicated.[26]

Patients suspected of having LCDD should be evaluated using the screening panel for plasma cell proliferative disorders.[27] However, the sensitivity of laboratory testing strategies for detecting monoclonal gammopathies has increased with the development of quantitative serum assays to test for immunoglobulin free light chain;[28] this increased diagnostic sensitivity is easily noticeable in the monoclonal light chain diseases.[29] The most recent diagnostic screening guidelines state that serum immunofixation in addition to immunoglobulin free light chain is an adequate screening panel for plasma cell proliferative disorders apart from AL amyloidosis and LCDD due to the increased sensitivity for free light chain diseases. It is advised, nevertheless, that urine immunofixation be used in addition to LCDD and AL amyloidosis screening.[27]

The immunohistologic examination of tissue from an afflicted organ—which is not congophilic in nature—confirms the diagnosis of LCDD. The tissue's light chain restriction evaluation will determine whether the heavy or light chain is monoclonal. An abdominal ultrasound and echocardiography should be part of the workup when an individual is diagnosed with LCDD in order to evaluate the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes. A bone marrow aspirate as well as biopsy are necessary to rule out light amyloidosis and/or multiple myeloma.[5]

Similar to cardiac amyloid, diastolic dysfunction and a decrease in myocardial compliance may be discovered via echocardiography and catheterization.[30]

By using specific light chain stains in glomeruli as well as negative Congo red stain, tubular basement membranes, and punctate amorphous, ground-pepper-like appearance of deposits on electron microscopy, LCDD can be differentiated from other causes of nodular sclerosis and mesangial expansion. Diabetic nephropathy exhibits no deposits; fibrillary glomerulonephritis is Congo red negative and has a proliferative appearance along with polyclonal immunoglobulin G; other monoclonal immunoglobulin deposition disease exhibit both light and heavy chain staining or just heavy chain staining. Additional reasons for a membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis pattern exhibit electron microscopy appearances and immunofluorescence specific to the disease.[31]

Treatment

[edit]Decreasing production of the organ-damaging light chains is the treatment goal. Options include chemotherapy using bortezomib, autologous stem cell transplantation, immunomodulatory drugs, and kidney transplant.[32] There is no standard treatment for LCDD. High-dose melphalan in conjunction with autologous stem cell transplantation has been used in some patients. A regimen of bortezomib and dexamethasone has also been examined.[1]

Outlook

[edit]Different light chain deposition does not appear to have an impact on the clinical course of LCDD patients, as the clinical presentation is known to depend on the quantity and type of affected organs.[33] The median survival time is roughly four years. Following a median follow-up of 27 months, the most comprehensive series to date found that 59% of cases resulted in death and 57% of cases reached uremia.[4] LCDD prognostic factors include age, extrarenal light chain deposition, and plasma cell myeloma.[34]

Epidemiology

[edit]Being a relatively rare condition, LCDD is commonly misdiagnosed as a protein disease. Up to 50% of patients receive an LCDD diagnosis as a result of lymphoproliferative disorders such as multiple myeloma.[35] LCDD is diagnosed at a median age of 58 years.[4] LCDD affects men 2.5 times more than women[8] and is frequently linked with monoclonal gammopathies of unknown significance in 17% of patients.[5]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Kastritis (February 2009). "Treatment of light chain deposition disease with bortezomib and dexamethasone". Haematologica. 94 (2): 300–302. doi:10.3324/haematol.13548. PMC 2635400. PMID 19066331.

- ^ UNC Kidney Center. "Light Chain Deposition Disease". UNC. Archived from the original on 22 December 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- ^ a b c Ronco, Pierre M; Alyanakian, Marie-Alexandra; Mougenot, Beatrice; Aucouturier, Pierre (July 2001). "Light chain deposition disease: a model of glomerulosclerosis defined at the molecular level". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 12 (7). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 1558–1565. doi:10.1681/asn.v1271558. ISSN 1046-6673. PMID 11423587. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ a b c d Pozzi, Claudio; D'Amico, Marco; Fogazzi, Giovanni B; Curioni, Simona; Ferrario, Franco; Pasquali, Sonia; Quattrocchio, Giacomo; Rollino, Cristiana; Segagni, Siro; Locatelli, Francesco (2003). "Light chain deposition disease with renal involvement: clinical characteristics and prognostic factors". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 42 (6). Elsevier BV: 1154–1163. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.08.040. ISSN 0272-6386. PMID 14655186.

- ^ a b c Jimenez-Zepeda, V. H. (2012). "Light chain deposition disease: novel biological insights and treatment advances". International Journal of Laboratory Hematology. 34 (4): 347–355. doi:10.1111/j.1751-553X.2012.01419.x. ISSN 1751-5521. PMID 22471811. S2CID 5900828.

- ^ Rostagno, Agueda; Frizzera, Glauco; Ylagan, Lourdes; Kumar, Asok; Ghiso, Jorge; Gallo, Gloria (2002). "Tumoral non-amyloidotic monoclonal immunoglobulin light chain deposits ('aggregoma'): presenting feature of B-cell dyscrasia in three cases with immunohistochemical and biochemical analyses". British Journal of Haematology. 119 (1). Wiley: 62–69. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03781.x. ISSN 0007-1048. PMID 12358904.

- ^ Croitoru, Anca; Hytiroglou, Prodromos; Schwartz, Myron E.; Saxena, Romil (2006). "Liver Transplantation for Liver Rupture Due to Light Chain Deposition Disease: A Case Report". Seminars in Liver Disease. 26 (3). Georg Thieme Verlag KG: 298–303. doi:10.1055/s-2006-947301. ISSN 0272-8087. PMID 16850379. S2CID 260320472.

- ^ a b Pozzi, Claudio; Locatelli, Francesco (2002). "Kidney and liver involvement in monoclonal light chain disorders". Seminars in Nephrology. 22 (4). Elsevier BV: 319–330. doi:10.1053/snep.2002.33673. ISSN 0270-9295. PMID 12118397.

- ^ Fabbian, Fabio; Stabellini, Nevio; Sartori, Sergio; Tombesi, Paola; Aleotti, Arrigo; Bergami, Maurizio; Uggeri, Simona; Galdi, Adriana; Molino, Christian; Catizone, Luigi (2007). "Light chain deposition disease presenting as paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: a case report". Journal of Medical Case Reports. 1 (1). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 187. doi:10.1186/1752-1947-1-187. ISSN 1752-1947. PMC 2254633. PMID 18163912.

- ^ p. Koopman; j. Van Dorpe; b. Maes; k. Dujardin (2009). "Light chain deposition disease as a rare cause of restrictive cardiomyopathy". Acta Cardiologica. 64 (6). Peeters online journals: 821–824. doi:10.2143/AC.64.6.2044752. PMID 20128164. S2CID 41656061.

- ^ Piard; Yaziji; Jarry; Assem; Martin; Bernard; Jacquot; Justrabo (1998). "Solitary plasmacytoma of the lung with light chain extracellular deposits: a case report and review of the literature". Histopathology. 32 (4). Wiley: 356–361. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2559.1998.00393.x. ISSN 0309-0167. PMID 9602333. S2CID 33700713.

- ^ Colombat, M.; Gounant, V.; Mal, H.; Callard, P.; Milleron, B. (May 1, 2007). "Light chain deposition disease involving the airways: diagnosis by fibreoptic bronchoscopy". European Respiratory Journal. 29 (5). European Respiratory Society (ERS): 1057–1060. doi:10.1183/09031936.00134406. ISSN 0903-1936. PMID 17470625.

- ^ Khoor, Andras; Myers, Jeffrey L.; Tazelaar, Henry D.; Kurtin, Paul J. (2004). "Amyloid-like Pulmonary Nodules, Including Localized Light-Chain Deposition". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 121 (2). Oxford University Press (OUP): 200–204. doi:10.1309/3gecpw2402f6v8ek. ISSN 0002-9173.

- ^ Grassi, M. P.; Clerici, F.; Perin, C.; Borella, M.; Mangoni, A.; Gendarini, A.; Quattrini, A.; Nemni, R. (1998). "Light chain deposition disease neuropathy resembling amyloid neuropathy in a multiple myeloma patient". The Italian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 19 (4). Springer Science and Business Media LLC: 229–233. doi:10.1007/bf02427609. ISSN 0392-0461. PMID 10933463. S2CID 1052811.

- ^ Gandhi, Dheeraj; Wee, Roberto; Goyal, Mayank (March 1, 2003). "CT and MR Imaging of Intracerebral Amyloidoma: Case Report and Review of the Literature". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 24 (3): 519–522. ISSN 0195-6108. PMC 7973613. PMID 12637308. Retrieved December 14, 2023.

- ^ Popović, Mara; Tavćar, Rok; Glavač, Damjan; Volavšek, Metka; Pirtošek, Zvezdan; Vizjak, Alenka (2007). "Light chain deposition disease restricted to the brain: the first case report". Human Pathology. 38 (1). Elsevier BV: 179–184. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2006.07.010. ISSN 0046-8177. PMID 17059841.

- ^ a b Vidal, Ruben; Goñi, Fernando; Stevens, Fred; Aucouturier, Pierre; Kumar, Asok; Frangione, Blas; Ghiso, Jorge; Gallo, Gloria (1999). "Somatic Mutations of the L12a Gene in V-κ1 Light Chain Deposition Disease". The American Journal of Pathology. 155 (6). Elsevier BV: 2009–2017. doi:10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65520-4. ISSN 0002-9440. PMC 1866929. PMID 10595931.

- ^ Denoroy, Luc; Déret, Sophie; Aucouturier, Pierre (1994). "Overrepresentation of the VκIV subgroup in light chain deposition disease" (PDF). Immunology Letters. 42 (1–2). Elsevier BV: 63–66. doi:10.1016/0165-2478(94)90036-1. ISSN 0165-2478. PMID 7829131.

- ^ Kattah, Andrea; Leung, Nelson (2019). "Light Chain Deposition Disease". Glomerulonephritis. Cham: Springer International Publishing. pp. 597–615. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-49379-4_39. ISBN 978-3-319-49378-7. S2CID 138289674.

- ^ ROCCA, A; KHAMLICHI, A A; AUCOUTURIER, P; NOËL, L-H; DENOROY, L; PREUD'HOMME, J-L; COGNÉ, M (1993). "Primary structure of a variable region of the VκI subgroup (ISE) in light chain deposition disease". Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 91 (3). Oxford University Press (OUP): 506–509. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.1993.tb05932.x. ISSN 0009-9104. PMC 1554718. PMID 7680298.

- ^ Decourt, Catherine; Touchard, Guy; Preud'homme, Jean-Louis; Vidal, Ruben; Beaufils, Hélène; Diemert, Marie-Claude; Cogné, Michel (1998). "Complete Primary Sequences of Two λ Immunoglobulin Light Chains in Myelomas with Nonamyloid (Randall-Type) Light Chain Deposition Disease". The American Journal of Pathology. 153 (1). Elsevier BV: 313–318. doi:10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65573-3. ISSN 0002-9440. PMC 1852939. PMID 9665493.

- ^ Khamlichi, AA; Rocca, A; Touchard, G; Aucouturier, P; Preud'homme, JL; Cogne, M (November 15, 1995). "Role of light chain variable region in myeloma with light chain deposition disease: evidence from an experimental model". Blood. 86 (10). American Society of Hematology: 3655–3659. doi:10.1182/blood.v86.10.3655.bloodjournal86103655. ISSN 0006-4971.

- ^ Cogné, M; Preud'homme, J L; Bauwens, M; Touchard, G; Aucouturier, P (June 1, 1991). "Structure of a monoclonal kappa chain of the V kappa IV subgroup in the kidney and plasma cells in light chain deposition disease". Journal of Clinical Investigation. 87 (6). American Society for Clinical Investigation: 2186–2190. doi:10.1172/jci115252. ISSN 0021-9738. PMC 296978. PMID 1904072.

- ^ Ronco, Pierre; Plaisier, Emmanuelle; Mougenot, Be[Combining Acute Accent]atrice; Aucouturier, Pierre (2006). "Immunoglobulin Light (Heavy)-Chain Deposition Disease". Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 1 (6). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 1342–1350. doi:10.2215/cjn.01730506. ISSN 1555-9041. PMID 17699367.

- ^ Keeling, John; Herrera, Guillermo A. (2009). "An in vitro model of light chain deposition disease". Kidney International. 75 (6). Elsevier BV: 634–645. doi:10.1038/ki.2008.504. ISSN 0085-2538. PMID 18923384.

- ^ "Light-Chain Deposition Disease Workup: Laboratory Studies, Imaging Studies, Procedures". emedicine.medscape.com. Retrieved 2018-04-17.

- ^ a b Katzmann, Jerry A; Kyle, Robert A; Benson, Joanne; Larson, Dirk R; Snyder, Melissa R; Lust, John A; Rajkumar, S Vincent; Dispenzieri, Angela (August 1, 2009). "Screening Panels for Detection of Monoclonal Gammopathies". Clinical Chemistry. 55 (8). Oxford University Press (OUP): 1517–1522. doi:10.1373/clinchem.2009.126664. ISSN 0009-9147. PMC 3773468. PMID 19520758.

- ^ Katzmann, Jerry A; Clark, Raynell J; Abraham, Roshini S; Bryant, Sandra; Lymp, James F; Bradwell, Arthur R; Kyle, Robert A (September 1, 2002). "Serum reference intervals and diagnostic ranges for free kappa and free lambda immunoglobulin light chains: relative sensitivity for detection of monoclonal light chains". Clinical Chemistry. 48 (9): 1437–1444. doi:10.1093/clinchem/48.9.1437. PMID 12194920. Retrieved 14 December 2023.

- ^ Dispenzieri, Angela; Lacy, Martha Q.; Katzmann, Jerry A.; Rajkumar, S. Vincent; Abraham, Roshini S.; Hayman, Suzanne R.; Kumar, Shaji K.; Clark, Raynell; Kyle, Robert A.; Litzow, Mark R.; Inwards, David J.; Ansell, Stephen M.; Micallef, Ivana M.; Porrata, Luis F.; Elliott, Michelle A.; Johnston, Patrick B.; Greipp, Philip R.; Witzig, Thomas E.; Zeldenrust, Steven R.; Russell, Stephen J.; Gastineau, Dennis; Gertz, Morie A. (April 15, 2006). "Absolute values of immunoglobulin free light chains are prognostic in patients with primary systemic amyloidosis undergoing peripheral blood stem cell transplantation". Blood. 107 (8). American Society of Hematology: 3378–3383. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-07-2922. ISSN 0006-4971. PMC 1895763. PMID 16397135.

- ^ Ganeval, Dominique; Noël, Laure-Hélène; Preud'homme, Jean-Louis; Droz, Dominique; Grünfeld, Jean-Pierre (1984). "Light-chain deposition disease: Its relation with AL-type amyloidosis". Kidney International. 26 (1). Elsevier BV: 1–9. doi:10.1038/ki.1984.126. ISSN 0085-2538. PMID 6434789.

- ^ Fogo, Agnes B.; Lusco, Mark A.; Najafian, Behzad; Alpers, Charles E. (2015). "AJKD Atlas of Renal Pathology: Light Chain Deposition Disease". American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 66 (6). Elsevier BV: e47–e48. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2015.10.007. ISSN 0272-6386. PMID 26593321.

- ^ "Light chain deposition disease | Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (GARD) – an NCATS Program". rarediseases.info.nih.gov. Retrieved 2018-04-18.

- ^ Kim, Hee-Jun; Park, Eunkyung; Lee, Tae Jin; Do, Jae Hyuk; Cha, Young Joo; Lee, Sang Jae (2012). "A Case of Isolated Light Chain Deposition Disease in the Duodenum". Journal of Korean Medical Science. 27 (2). Korean Academy of Medical Sciences: 207–210. doi:10.3346/jkms.2012.27.2.207. ISSN 1011-8934. PMC 3271296. PMID 22323870.

- ^ LIN, JULIE; MARKOWITZ, GLEN S.; VALERI, ANTHONY M.; KAMBHAM, NEERAJA; SHERMAN, WILLIAM H.; APPEL, GERALD B.; D'AGATI, VIVETTE D. (2001). "Renal Monoclonal Immunoglobulin Deposition Disease". Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 12 (7). Ovid Technologies (Wolters Kluwer Health): 1482–1492. doi:10.1681/asn.v1271482. ISSN 1046-6673. PMID 11423577.

- ^ Wang, Qi; Jiang, Fang; Xu, Gaosi (2019). "The pathogenesis of renal injury and treatment in light chain deposition disease". Journal of Translational Medicine. 17 (1): 387. doi:10.1186/s12967-019-02147-4. ISSN 1479-5876. PMC 6878616. PMID 31767034.

Further reading

[edit]- Masood, Adeel; Ehsan, Hamid; Iqbal, Qamar; Salman, Ahmed; Hashmi, Hamza (2022). "Treatment of Light Chain Deposition Disease: A Systematic Review". Journal of Hematology. 11 (4). Elmer Press, Inc.: 123–130. doi:10.14740/jh1038. ISSN 1927-1212. PMC 9451548. PMID 36118549.