Armored car (military)

| Part of a series on |

| War (outline) |

|---|

|

A military armored (also spelled armoured) car is a wheeled armoured fighting vehicle, historically employed for reconnaissance, internal security, armed escort, and other subordinate battlefield tasks.[1] With the gradual decline of mounted cavalry, armored cars were developed for carrying out duties formerly assigned to light cavalry.[2] Following the invention of the tank, the armoured car remained popular due to its faster speed, comparatively simple maintenance and low production cost. It also found favor with several colonial armies as a cheaper weapon for use in underdeveloped regions.[3] During World War II, most armoured cars were engineered for reconnaissance and passive observation, while others were devoted to communications tasks. Some equipped with heavier armament could even substitute for tracked combat vehicles in favorable conditions—such as pursuit or flanking maneuvers during the North African campaign.[3]

Since World War II the traditional functions of the armored car have been occasionally combined with that of the armoured personnel carrier, resulting in such multipurpose designs as the BTR-40 or the Cadillac Gage Commando.[2] Postwar advances in recoil control technology have also made it possible for a few armoured cars, including the B1 Centauro, the Panhard AML, the AMX-10 RC and EE-9 Cascavel, to carry a large cannon capable of threatening many tanks.[4]

History

[edit]Precursors

[edit]During the Middle Ages, war wagons covered with steel plate, and crewed by men armed with primitive hand cannon, flails and muskets, were used by the Hussite rebels in Bohemia. These were deployed in formations where the horses and oxen were at the centre, and the surrounding wagons were chained together as protection from enemy cavalry.[5] With the invention of the steam engine, Victorian inventors designed prototype self-propelled armored vehicles for use in sieges, although none were deployed in combat. H. G. Wells' short story "The Land Ironclads" provides a fictionalized account of their use.[6]

Armed car

[edit]

The Motor Scout was designed and built by British inventor F.R. Simms in 1898. It was the first armed petrol engine-powered vehicle ever built. The vehicle was a De Dion-Bouton quadricycle with a mounted Maxim machine gun on the front bar. An iron shield in front of the car protected the driver.[7]

Another early armed car was invented by Royal Page Davidson at Northwestern Military and Naval Academy in 1898 with the Davidson-Duryea gun carriage and the later Davidson Automobile Battery armored car.

However, these were not "armored cars" as the term is understood today, as they provided little protection for their crews from enemy fire.

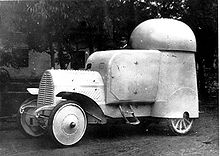

First armoured cars

[edit]At the beginning of the 20th century, the first military armored vehicles were manufactured by adding armor and weapons to existing vehicles.

The first armored car was the Simms' Motor War Car, designed by F.R. Simms and built by Vickers, Sons & Maxim of Barrow on a special Coventry-built Daimler chassis[8] with a German-built Daimler motor in 1899.[8] and a single prototype was ordered in April 1899[8] The prototype was finished in 1902,[8] too late to be used during the Boer War.

The vehicle had Vickers armor, 6 mm (0.24 in) thick, and was powered by a four-cylinder 3.3 L (200 cu in)[8] 16 hp (12 kW) Cannstatt Daimler engine, giving it a maximum speed of around 9 mph (14 km/h). The armament, consisting of two Maxim guns, was carried in two turrets with 360° traverse.[9][10] It had a crew of four. Simms' Motor War Car was presented at the Crystal Palace, London, in April 1902.[11]

Another early armored car of the period was the French Charron, Girardot et Voigt 1902, presented at the Salon de l'Automobile et du cycle in Brussels, on 8 March 1902.[12] The vehicle was equipped with a Hotchkiss machine gun, and with 7 mm (0.28 in) armour for the gunner.[13][14]

One of the first operational armored cars with four wheel (4x4) drive and partly enclosed rotating turret, was the Austro-Daimler Panzerwagen built by Austro-Daimler in 1904. It was armored with 3–3.5 mm (0.12–0.14 in) thick curved plates over the body (drive space and engine) and had a 4 mm (0.16 in) thick dome-shaped rotating turret that housed one or two machine-guns. It had a four-cylinder 35 hp (26 kW) 4.4 L (270 cu in) engine giving it average cross country performance. Both the driver and co-driver had adjustable seats enabling them to raise them to see out of the roof of the drive compartment as needed.[15]

The Spanish Schneider-Brillié was the first armored vehicle to be used in combat, being first used in the Kert Campaign. The vehicle was equipped with two machineguns and built from a bus chassis.[16]

An armored car known as the ''Death Special'' was built at the CFI plant in Pueblo and used by the Badlwin-Felts detective agency during the Colorado Coalfield War.[17]

World War I

[edit]A great variety of armored cars appeared on both sides during World War I and these were used in various ways. Generally, armored cars were used by more or less independent car commanders. However, sometimes they were used in larger units up to squadron size. The cars were primarily armed with light machine guns, but larger units usually employed a few cars with heavier guns. As air power became a factor, armored cars offered a mobile platform for antiaircraft guns.[18]

The first effective use of an armored vehicle in combat was achieved by the Belgian Army in August–September 1914. They had placed Cockerill armour plating and a Hotchkiss machine gun on Minerva touring cars, creating the Minerva Armored Car. Their successes in the early days of the war convinced the Belgian GHQ to create a Corps of Armoured Cars, who would be sent to fight on the Eastern front once the western front immobilized after the Battle of the Yser.[19][20][21]

The British Royal Naval Air Service dispatched aircraft to Dunkirk to defend the UK from Zeppelins. The officers' cars followed them and these began to be used to rescue downed reconnaissance pilots in the battle areas. They mounted machine guns on them[22] and as these excursions became increasingly dangerous, they improvised boiler plate armoring on the vehicles provided by a local shipbuilder. In London Murray Sueter ordered "fighting cars" based on Rolls-Royce, Talbot and Wolseley chassis. By the time Rolls-Royce Armoured Cars arrived in December 1914, the mobile period on the Western Front was already over.[23]

More tactically important was the development of formed units of armored cars, such as the Canadian Automobile Machine Gun Brigade, which was the first fully mechanized unit in the history. The brigade was established on September 2, 1914, in Ottawa, as Automobile Machine Gun Brigade No. 1 by Brigadier-General Raymond Brutinel. The brigade was originally equipped with eight Armoured Autocars mounting two machine guns. By 1918 Brutinel's force consisted of two motor machine gun brigades (each of five gun batteries containing eight weapons apiece).[24] The brigade, and its armored cars, provided yeoman service in many battles, notably at Amiens.[25] The RNAS section became the Royal Naval Armoured Car Division reaching a strength of 20 squadrons before disbanded in 1915. and the armoured cars passing to the army as part of the Machine Gun Corps. Only NO.1 Squadron was retained; it was sent to Russia. As the Western Front turned to trench warfare unsuitable to wheeled vehicles, the armoured cars were moved to other areas.

The 2nd Duke of Westminster took No. 2 Squadron of the RNAS to France in March 1915 in time to make a noted contribution to the Second Battle of Ypres, and thereafter the cars with their master were sent to the Middle East to play a part in the British campaign in Palestine and elsewhere[26] The Duke led a motorised convoy including nine armoured cars across the Western Desert in North Africa to rescue the survivors of the sinking of the SS Tara which had been kidnapped and taken to Bir Hakiem.

In Africa, Rolls Royce armoured cars were active in German South West Africa and Lanchester Armoured Cars in British East Africa against German forces to the south.

Armored cars also saw action on the Eastern Front. From 18 February - 26 March 1915, the German army under General Max von Gallwitz attempted to break through the Russian lines in and around the town of Przasnysz, Poland, (about 110 km / 68 miles north of Warsaw) during the Battle of Przasnysz (Polish: Bitwa przasnyska). Near the end of the battle, the Russians used four Russo-Balt armored cars and a Mannesmann-MULAG armored car to break through the Germans' lines and force the Germans to retreat.[27]

World War II

[edit]The British Royal Air Force (RAF) in the Middle East was equipped with Rolls-Royce Armoured Cars and Morris tenders. Some of these vehicles were among the last of a consignment of ex-Royal Navy armored cars that had been serving in the Middle East since 1915.[28] In September 1940 a section of the No. 2 Squadron RAF Regiment Company was detached to General Wavell's ground forces during the first offensive against the Italians in Egypt. During the actions in the October of that year the company was employed on convoy escort tasks, airfield defense, fighting reconnaissance patrols and screening operations.

During the 1941 Anglo-Iraqi War, some of the units located in the British Mandate of Palestine[29] were sent to Iraq and drove Fordson armored cars.[30] "Fordson" armored cars were Rolls-Royce armored cars which received new chassis from a Fordson truck in Egypt.

By the start of the new war, the German army possessed some highly effective reconnaissance vehicles, such as the Schwerer Panzerspähwagen. The Soviet BA-64 was influenced by a captured Leichter Panzerspähwagen before it was first tested in January 1942.

In the second half of the war, the American M8 Greyhound and the British Daimler Armoured Cars featured turrets mounting light guns (40 mm or less). As with other wartime armored cars, their reconnaissance roles emphasized greater speed and stealth than a tracked vehicle could provide, so their limited armor, armament and off-road capabilities were seen as acceptable compromises.

Military use

[edit]A military armored car is a type of armored fighting vehicle having wheels (from four to ten large, off-road wheels) instead of tracks, and usually light armor. Armored cars are typically less expensive and on roads have better speed and range than tracked military vehicles. They do however have less mobility as they have less off-road capabilities because of the higher ground pressure. They also have less obstacle climbing capabilities than tracked vehicles. Wheels are more vulnerable to enemy fire than tracks, they have a higher signature and in most cases less armor than comparable tracked vehicles. As a result, they are not intended for heavy fighting; their normal use is for reconnaissance, command, control, and communications, or for use against lightly armed insurgents or rioters. Only some are intended to enter close combat, often accompanying convoys to protect soft-skinned vehicles.

Light armored cars, such as the British Ferret are armed with just a machine gun. Heavier vehicles are armed with autocannon or a large caliber gun. The heaviest armored cars, such as the German, World War II era Sd.Kfz. 234 or the modern, US M1128 mobile gun system, mount the same guns that arm medium tanks.

Armored cars are popular for peacekeeping or internal security duties. Their appearance is less confrontational and threatening than tanks, and their size and maneuverability is said to be more compatible with tight urban spaces designed for wheeled vehicles. However, they do have a larger turning radius compared to tracked vehicles which can turn on the spot and their tires are vulnerable and are less capable in climbing and crushing obstacles. Further, when there is true combat they are easily outgunned and lightly armored. The threatening appearance of a tank is often enough to keep an opponent from attacking, whereas a less threatening vehicle such as an armored car is more likely to be attacked.

Many modern forces now have their dedicated armored car designs, to exploit the advantages noted above. Examples would be the M1117 armored security vehicle of the USA or Alvis Saladin of the post-World War II era in the United Kingdom.

Alternatively, civilian vehicles may be modified into improvised armored cars in ad hoc fashion.[31] Many militias and irregular forces adapt civilian vehicles into AFVs (armored fighting vehicles) and troop carriers, and in some regional conflicts these "technicals" are the only combat vehicles present. On occasion, even the soldiers of national militaries are forced to adapt their civilian-type vehicles for combat use, often using improvised armor and scrounged weapons.

Scout cars

[edit]In the 1930s, a new sub-class of armored car emerged in the United States, known as the scout car. This was a compact light armored car which was either unarmed or armed only with machine guns for self-defense.[32] Scout cars were designed as purpose-built reconnaissance vehicles for passive observation and intelligence gathering.[32] Armored cars which carried large caliber, turreted weapons systems were not considered scout cars.[32] The concept gained popularity worldwide during World War II and was especially favored in nations where reconnaissance theory emphasized passive observation over combat.[33]

Examples of armored cars also classified as scout cars include the Soviet BRDM series, the British Ferret, the Brazilian EE-3 Jararaca, the Hungarian D-442 FÚG, and the American Cadillac Gage Commando Scout.[34]

See also

[edit]

- Armored bus

- Armored personnel carrier

- Armored car (valuables)

- Armored car (VIP)

- Armoring:

- Gun truck

- SWAT vehicle

- Tankette

- Technical (vehicle)

Notes

[edit]- ^ Lepage, Jean-Denis G.G. (7 March 2007). German Military Vehicles of World War II: An Illustrated Guide to Cars, Trucks, Half-Tracks, Motorcycles, Amphibious Vehicles and Others (2007 ed.). McFarland & Company. pp. 169–172. ISBN 978-0786428984.

- ^ a b Bull, Stephen (2004). Encyclopedia of Military Technology and Innovation (2004 ed.). Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 19–20. ISBN 978-1573565578.

- ^ a b Bradford, James (2006). International Encyclopedia of Military History (2006 ed.). Routledge Books. pp. 97–98. ISBN 978-0415936613.

- ^ Dougherty, Martin J. (15 December 2012). Modern Weapons: Compared and Contrasted: Armored Fighting Vehicles (2012 ed.). Rosen Central. pp. 34–36. ISBN 978-1448892440.

- ^ Knighton, Andrew (12 July 2016). "Circling the 15th Century Wagons: The Hussite Wars". warhistoryonline.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2018. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ "The Land Ironclads". gutenberg.net.au. Archived from the original on 19 August 2017. Retrieved 6 May 2018.

- ^ Macksey, Kenneth (1980). The Guinness Book of Tank Facts and Feats. Guinness Superlatives Limited, ISBN 0-85112-204-3.

- ^ a b c d e Edward John Barrington Douglas-Scott-Montagu Baron Montagu of Beaulieu; Lord Montagu; David Burgess Wise (1995). Daimler Century: The Full History of Britain's Oldest Car Maker. Haynes Publications. ISBN 978-1-85260-494-3.

- ^ Macksey, Kenneth (1980). The Guinness Book of Tank Facts and Feats. Guinness Superlatives Limited. p. 256. ISBN 0-85112-204-3.

- ^ Tucker, Spencer (1999). The European Powers in the First World War. Routledge. p. 816. ISBN 0-8153-3351-X.

- ^ Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the World, Duncan, p.3

- ^ Gougaud, Alain (1987). L'aube de la gloire: les autos mitrailleuses et les chars français pendant la Grande Guerre, histoire technique et militaire, arme blindée, cavalerie, chars, Musée des blindés. Société OCEBUR. p. 11. ISBN 978-2-904255-02-1.

- ^ Bartholomew, E. (1 January 1988). Early Armoured Cars. Bloomsbury USA. ISBN 9780852639085 – via Google Books.

- ^ Gougaud, p.11-12

- ^ "Austro-Daimler Panzerwagen (1904)". www.tanks-encyclopedia.com. Archived from the original on 2017-04-29.

- ^ Montes, Gareth Lynn (2018-12-20). "Blindado Schneider-Brillié". Tank Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2023-04-18.

- ^ Program, Colorado Digitization. "Colorado Coal Field War Project". www.du.edu. Retrieved 2023-04-18.

- ^ Crow, Encyclopedia of Armored Cars, pg. 25

- ^ "WWI - Belgium Armoured Car Division in Russia". 16 April 2011. Archived from the original on 2013-10-02.

- ^ "Foreign armoured units at Russian front during WWI". www.wio.ru. Archived from the original on 2012-06-12.

- ^ "Belgian Armoured Cars in Russia". Archived from the original on 2011-05-19. Retrieved 2011-02-17.

- ^ Band of Brigands p 59

- ^ First World War - Willmott, H.P., Dorling Kindersley, 2003, Pg. 59

- ^ P. Griffith p 129 "Battle Tactics on the Western Front - The British Army's art of attack 1916–18 Yale university Press quoting the Official History 1918 vol.4, p42

- ^ Cameron Pulsifer (2007). ' 'The Armoured Autocar in Canadian Service' ', Service Publications

- ^ Verdin, Lt.-Col. Sir Richard (1971). The Cheshire (Earl of Chester's) Yeomanry. Birkenhead: Willmer Bros. Ltd. pp. 50–51.

- ^ Do broni : Bitwa Przasnyska (luty 1915) (To arms: the Battle of Przasnysz (February 1915)) Archived 2018-01-07 at the Wayback Machine (in Polish)

- ^ Lyman, Iraq 1941, pg. 40

- ^ Lyman, p. 57

- ^ Lyman, Iraq 1941, pg. 25

- ^ Cybertruck, Kadyrov-adapted. "Tesla vehicle in Associated Press report".

- ^ a b c Green, Michael (2017). Allied Armoured Fighting Vehicles of the Second World War. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Military Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-1473872370.

- ^ Van Oosbree, Gerard (July–August 1999). "Dutch and Germans Agree to Build "Fennek" Light Reconnaissance Vehicle". Armor magazine. Fort Knox, Kentucky: US Army Armor Center: 34.

- ^ Chant, Christopher (1987). A Compendium of Armaments and Military Hardware. New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 28–38. ISBN 0-7102-0720-4. OCLC 14965544.

References

[edit]- Crow, Duncan, and Icks, Robert J., Encyclopedia of Armored Cars, Chatwell Books, Secaucus, NJ, 1976. ISBN 0-89009-058-0.

- Duncan, Major-general N. W. Early Armoured Cars. AFV Profile No 9. Windsor: Profile Publishing.