Tangutology

Tangutology or Tangut studies is the study of the culture, history, art and language of the ancient Tangut people, especially as seen through the study of contemporaneous documents written by the Tangut people themselves.[1][2] As the Tangut language was written in a unique and complex script and the spoken language became extinct, the cornerstone of Tangut studies has been the study of the Tangut language and the decipherment of the Tangut script.

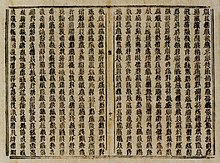

The Tangut people founded the Western Xia dynasty (1038–1227) in northwestern China, which was eventually overthrown by the Mongols. The Tangut script, which was devised in 1036, was widely used in printed books and on monumental inscriptions during the Western Xia period, as well as during the Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), but the language became extinct sometime during the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). The latest known examples of Tangut writing are Buddhist inscriptions dated 1502 on two dharani pillars from a temple in Baoding, Hebei.[3][4] By the Qing dynasty (1644–1912) all knowledge of the Tangut language and script had been lost, and no examples or descriptions of the Tangut script had been preserved in any surviving Chinese books from the Song, Yuan or Ming dynasties. It was not until the 19th century that the Tangut language and script were rediscovered.

The birth of Tangut studies

[edit]Earliest identification of Tangut

[edit]

The earliest modern identification of the Tangut script occurred in 1804, when a Chinese scholar called Zhang Shu (Chinese: 張澍; pinyin: Zhāng Shù, 1781–1847) observed that the Chinese text of a Chinese-Tangut bilingual inscription on a stele known as the Liangzhou Stele at the Huguo Temple (護國寺) in Wuwei, Gansu, had a Western Xia era name, and so concluded that the corresponding inscription in an unknown script must be the native Western Xia script; and hence the unknown writing in the same style on the Cloud Platform at Juyongguan at the Great Wall of China north of Beijing must also be the Tangut script.[1]

However, Zhang's identification of the Tangut script was not widely known, and more than a half a century later scholars were still debating what the unknown script at the Cloud Platform was. The Cloud Platform, which had been built in 1343–1345 as the base for a pagoda, was inscribed with Buddhist texts in six different scripts (Chinese, Sanskrit, ʼPhags-pa, Tibetan, Old Uyghur and Tangut), but only the first five of these six were known to Chinese and Western scholars at the time. In 1870 Alexander Wylie (1815–1887) wrote an influential paper entitled "An ancient Buddhist inscription at Keu-yung Kwan" in which he asserted that the unknown script was Jurchen, and it was not until 1899 that Stephen Wootton Bushell (1844–1908) published a paper demonstrating conclusively that the unknown script was in fact Tangut.[5]

Tentative decipherments of Tangut

[edit]

Bushell, a physician at the British Legation in Beijing from 1868 to 1900, was a keen numismatist, and had collected a number of coins issued by the Western Xia state with inscriptions in the Tangut script. In order to read the inscriptions on these coins he attempted to decipher as many Tangut characters as possible by comparing the Chinese and Tangut texts on a bilingual stele from Liangzhou. In 1896 he published a list of thirty-seven Tangut characters with their corresponding meaning in Chinese, and using this key he was able to decipher the four-character inscription on one of his Western Xia coins as meaning "Precious Coin of the Da'an period [1076–1085]" (corresponding to the Chinese Dà'ān Bǎoqián 大安寶錢).[6] This was the first time that an unknown Tangut text, albeit only four characters in length, had been translated.[7]

At about the same time as Bushell was working on Tangut numismatic inscriptions, Gabriel Devéria (1844–1899), a diplomat at the French Legation in Beijing, was studying the bilingual Tangut-Chinese Liangzhou Stele, and in 1898, a year before his death, he published two important articles on the Tangut script and the Liangzhou Stele.

The third European in China to undertake the study of Tangut was Georges Morisse (d. 1910), an interpreter at the French Legation in Beijing, who made progress in deciphering the Tangut script by comparing the text of the Chinese version of the Lotus Sutra (Sanskrit: Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtra) with that of three volumes of a manuscript of the Tangut version which had been discovered in Beijing in 1900 during the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion.[8] By comparing the Tangut version of the sutra with the corresponding Chinese version of the sutra, Morisse was able to identify some 200 Tangut characters, and deduce some grammatical rules for Tangut, which he published in 1904.[1][9]

The development of Tangut studies (1908 to the 1930s)

[edit]

The paucity of surviving Tangut texts and inscriptions, and in particular the lack of any dictionary or glossary of the language, meant that it was difficult for scholars to go beyond the preliminary work on the decipherment of Tangut by Bushell and Morisse. The breakthrough in Tangut studies finally came in 1908 when Pyotr Kozlov discovered the abandoned Western Xia fortress city of Khara-Khoto on the edge of the Gobi Desert in Inner Mongolia. Khara-Khoto had been abruptly abandoned at the beginning of the Ming Dynasty, and, partially covered by sand, it had remained largely untouched for over 500 years. Inside a large stupa outside the city walls Kozlov discovered a hoard of some 2,000 printed books and manuscripts, mostly in Chinese and Tangut, as well as many pieces of Tangut Buddhist art, which he sent back to the Russian Geographical Society in Saint Petersburg for preservation and study. The material was subsequently transferred to the Asiatic Museum of the Academy of Sciences, which later became the Saint Petersburg branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (now the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts).[10] It was the discovery of this unprecedented hoard of Tangut material by Kozlov that led to the development of Tangutology as a separate academic discipline within the field of oriental studies.[1][2][11]

Russia

[edit]

After the arrival of the Khara-Khoto material in Saint Petersburg in autumn 1909, sinologist Aleksei Ivanovich Ivanov (1878–1937) worked on the preservation and identification of the hundreds of books and manuscripts that were written in the Tangut script, and it was not long before he discovered a bilingual Chinese-Tangut glossary called the Pearl in the Palm (Chinese: 番漢合時掌中珠; pinyin: Fān-Hàn Héshí Zhǎngzhōngzhū) which he immediately realised was the key to deciphering the Tangut language. He later discovered three monolingual Tangut dictionaries and glossaries among the Khara-Khoto material: Homophones (Chinese: 音同; pinyin: Yīntóng); Sea of Characters (Chinese: 文海; pinyin: Wénhǎi); and Mixed Characters (Chinese: 雜字; pinyin: Zázì). Ivanov published a number of articles on the Tangut script between 1909 and 1920, which helped disseminate knowledge of the Tangut script, and encouraged other scholars to study the language. In 1916, based on the material published by Ivanov, the German orientalist Berthold Laufer (1874–1934) published a study of the Tangut language in which he attempted to reconstruct the pronunciations of some characters, and in which he proposed that the Tangut language belonged to the Lolo-Moso branch of the Tibeto-Burman family.[1]

Based on the Pearl in the Palm and the other dictionaries, Ivanov was able to compile a short dictionary of about 3,000 Tangut characters. His dictionary was completed in 1918, but it was not published due to the political instability of the time. Ivanov deposited the manuscript of his dictionary at the Asiatic Museum, but he took it back home in 1922, and it disappeared after his arrest and execution in 1937, a victim of Stalin's Great Purge.[10]

Following on from Ivanov was Nikolai Aleksandrovich Nevsky (1892–1937). Nevsky had been resident in Japan since 1915, where he had studied the Japanese, Ainu and Tsou languages, but after he met Ivanov in China in 1925 he started to work on the study of the Tangut texts from Khara-Khoto and the decipherment of the Tangut script. In 1929 Nevsky moved back to the Soviet Union to work at the Institute of Oriental Studies in Leningrad, where he worked on a dictionary of Tangut based on the lexical materials found at Khara-Khoto. However, in late autumn 1937, before his dictionary was ready for publication, he and his Japanese wife were arrested and executed, thereby bringing a brutal end to the study of the Tangut language in the Soviet Union.[12]

China

[edit]In 1912 the renowned antiquarian Luo Zhenyu (1866–1940) met Ivanov in Saint Petersburg, and he was allowed to make a copy of nine pages from the Pearl in the Palm, which he published in China in the same year. He met Ivanov again in 1922 in Tianjin, and obtained a complete copy of the Pearl in the Palm, which was subsequently published by his eldest son, Luo Fucheng (羅福成, 1885–1960), in 1924. Luo Fucheng also published the first facsimile edition of the Homophones in 1935.[1] Luo's third son, Luo Fuchang (羅福萇, 1896–1921) shared the family's interest in Tangut, and wrote an influential handbook on the Tangut script when he was just eighteen years old.

Further discoveries of Tangut texts were made in China, most notably a cache of Buddhist sutras in five pottery jars that were unearthed in Lingwu in Ningxia in 1917. These texts were sent to Peiping, and form the nucleus of the Tangut collection of the National Library of China. A special issue of the Bulletin of the National Library of Peiping dedicated to these texts was published in 1932, with articles written by a variety of Chinese, Japanese and Russian scholars (Luo Fucheng, Wang Jingru, Ishihama Juntarō (石浜純太郎), Ivanov, and Nevsky).[1]

Elsewhere

[edit]During the late 1920s and early 1930s, a number of scholars, including Nevsky in Russia, Laufer in Germany, Wang Jingru 王靜如 (1903–1990) in China, and Stuart N. Wolfenden (1889–1938) at the University of California, Berkeley in the US, focussed their attention on several manuscripts from Khara-Khoto that had Tibetan phonetic glosses to Tangut texts, which enabled them to reconstruct some of the phonetic features of Tangut.

Meanwhile, in England, Gerard Clauson (1891–1974) had started to study the thousands of Tangut manuscript fragments that had been recovered from Khara-Khoto between 1913 and 1916 by Aurel Stein, and deposited at the British Museum in London. During 1937 and 1938 Clauson wrote a Skeleton dictionary of the Hsi-hsia language,[13] which was published in facsimile in 2016.[14]

However, with the Second Sino-Japanese War raging in the Far East, and political repression in the Soviet Union, Tangut studies ground to a halt in China, Japan and the Soviet Union during the late 1930s. With the onset of World War II Tangut studies stagnated in Europe and America as well.

-

Luo Fucheng

-

Luo Fuchang

-

Wang Jingru

The resurgence of Tangut studies (1950s through 1990s)

[edit]Japan

[edit]It was more than ten years after the end of World War II before there was a resurgence in Tangut studies. The first post-war scholar to turn his hand to Tangut was Nishida Tatsuo (西田龍雄, 1928–2012) of Kyoto University who started off by studying the Tangut Buddhist inscription on the Cloud Platform in the mid-1950s, and went on to become the pre-eminent Japanese scholar of Tangut for the next fifty years. In 1964–1966 Nishida produced a monumental work on the reconstruction of Tangut phonology and decipherment of Tangut characters, which included a dictionary of about 3,000 characters.[15]

Nishida also made studies of the Flower Garland Sutra (1975–1977) and Tangut ritual poems (1986). In order to explain the fact that in some ritual poems each line was written twice using different vocabulary and different grammatical structures, Nishida proposed that there were two different Tangut language registers: most Tangut text represented the language of the ordinary Tangut people (the "red-faced people"), but the ritual poems represented the language of the ruling class (the "black-headed people"), the latter preserving a linguistic substratum that had been lost in ordinary Tangut speech.[16]

Soviet Union

[edit]In the Soviet Union, Tangut studies were given a kickstart by the posthumous publication of Nevsky's magnum opus, Tangut Philology, in 1960, which won the Lenin Prize in 1962. The main part of Tangut Philology was a thousand-page manuscript draft dictionary of Tangut, which was the first modern dictionary of Tangut to be published, and opened up the study of Tangut texts to a new generation of scholars. During the 1960s a group of young scholars at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts in Leningrad, led by E. I. Kychanov, started to study and translate the huge hoard of Tangut texts that had been brought back from Khara-Khoto nearly half a century earlier.[12] One of the main fruits of this research was a scholarly edition by Kychanov, Ksenia Kepping, V. S. Kolokolov, and A. P. Terent'ev-Katanskij of the Tangut monolingual rhyming dictionary, the Sea of Characters (1969). Kolokolov and Kychanov had previously worked on an edition of the Tangut translations of the Chinese Confucian classics, which was especially noteworthy because the texts were written in a cursive form of the Tangut script which was very hard to read. Kepping, whose early research made important contributions to the understanding of Tangut grammar, went on to translate the Tangut translation of the Chinese military treatise Sun Tzu (1979). Kepping also extended Nishida's theory of two different types of Tangut language, proposing that one style of language represented the "common language" and the other style of language represented a "ritual language" that had been created by Tangut shamans for ritual purposes prior to the adoption of Buddhism. Terent'ev-Katanskij went on to produce a treatise on the technical features of Tangut books (1981). Another influential Russian scholar was Mikhail Sofronov, who in 1968 published an influential Grammar of the Tangut Language.[12][15]

In addition to working on the Tangut language and script, scholars such as Kychanov and Kepping also made important contributions to the understanding of Tangut history, society and religion. In 1968 Kychanov published an historical sketch of the Tangut state that provided the first systematic overview of Tangut history.[1] Kepping studied the relationship between state and religion during the Western Xia, and advocated the theory that the practice of Tantric Buddhism by the Emperor and Empress was central to the running of the Tangut state.[17]

China

[edit]In China, Tangut studies were slower to resume, and progress was hindered by the Cultural Revolution, so it was not until the second half of the 1970s that any significant research on Tangut was published.[18] One of the first of a new generation of Tangutologists was Li Fanwen, who started his career excavating fragments of Tangut epitaphs from the Western Xia imperial tombs during the early 1970s, then published a study of the Homophones in 1976, and went on to publish the first comprehensive Tangut-Chinese dictionary in 1997.[4] Other young scholars included Shi Jinbo, Bai Bin and Huang Zhenhua, who together produced an important study and translation of the Sea of Characters in 1983.

In Taiwan, Gong Hwang-cherng (1934–2010), who specialized in Sino-Tibetan comparative linguistics, worked on Tangut phonology, and provided the phonetic reconstructions for Li Fanwen's 1997 dictionary.

A number of important archaeological discoveries were made in China during this period, perhaps the most significant being the discovery of various historical and religious artefacts, as well as a number of Tangut manuscripts and printed texts, in the ruins of the Baisigou Square Pagoda in Ningxia in 1991 after it had been illegally blown up.[19] These included a previously unknown Tangut Buddhist text, the Auspicious Tantra of All-Reaching Union, which is thought to have been printed during the second half of the 12th century, and is believed to be the earliest extant example of a book printed using wooden movable type.[20]

Tangut Buddhism has also been an important topic of study for Chinese scholars. In 1988 Shi Jinbo produced an influential overview of Tangut Buddhism and Tangut Buddhist art.[21] Another scholar in this field is Xie Jisheng, who has made studies of Tangut Thangkas and has explored the influence of Tibetan Tantric Buddhism on Tangut Buddhist art.[21]

United States

[edit]In America there have been few scholars working on Tangut. During the 1970s Luc Kwanten worked on Tangu foreign relations,[15] and in 1982 he published a study of the Tangut-Chinese glossary, the Pearl in the Palm. However, the leading expert on Western Xia history and the Tangut people in the USA is Ruth W. Dunnell. In 1988 Dunnell made a study and translation of a bilingual Tangut and Chinese inscription on a stele erected in 1094, and in 1996 she published an influential book entitled The Great State of White and High: Buddhism and State Foundation in Eleventh-Century Xia in which she examined the relationship between the Tanguts and their neighbours, and the role of the Buddhism in the Tangut state.[22]

United Kingdom

[edit]Following in Clauson's tracks was Eric Grinstead, originally from New Zealand, who worked at the British Museum during the 1960s. He identified a unique Tangut translation of a Chinese work on military strategy ascribed to Zhuge Liang entitled The General's Garden in the British Museum's Stein Collection,[23] and edited a facsimile compilation of Tangut Buddhist texts in nine volumes, published in 1971 under the title The Tangut Tripitaka.[24] Grinstead's major publication was his Analysis of the Tangut Script (1972) in which he analysed the structure of the Tangut script, and assigned a four-digit 'Telecode' number to each Tangut character in an early attempt to assign standard codes to characters for use in computer processing of Tangut text.[25]

-

Nie Hongyin

Tangut studies in the 21st century

[edit]Since the late 1990s a new generation of Tangutologists has emerged. In China, a number of young scholars have made important contributions to Tangutology: Sun Bojun 孫伯君 has worked on Tangut translations of Sanskrit texts; Tai Chung-pui 戴忠沛 has made studies of Tibetan phonetic glosses of Tangut texts; and Han Xiaomang 韩小忙 has attempted to define the orthographic forms of Tangut characters.[25] In Japan, Arakawa Shintarō has concentrated on Tangut phonology, and produced a rhyming dictionary of Tangut. In the US, Marc Miyake has attempted to reconstruct a hypothetical ancestor to the Tangut language which he calls Pre-Tangut. In France, Guillaume Jacques has furthered the understanding of the verb in Tangut language. In the UK, Imre Galambos has continued the work of Grinstead in the study of Tangut manuscripts from Khara-Khoto held at the British Library, in particular The General's Garden.[26]

Established Tangutologists have also continued to make important contributions. Li Fanwen published a revised and extended edition of his Tangut-Chinese dictionary (2008), and Kychanov and Arakawa produced a Tangut-Russian-English-Chinese dictionary (2006). In 2021 Han Xiaomang published a dictionary of Tangut characters and words in nine volumes.

The ability for scholars around the world to study original Tangut documents has been greatly improved by the digitization of Tangut manuscripts from Khara-Khoto and elsewhere by the International Dunhuang Project (IDP), established by the British Library in 1994.[27] As of 7 May 2022[update] the online IDP database included 4,230 catalogue entries for Tangut manuscripts and printed texts held at the British Library in London, the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts in Saint Petersburg, Academia Sinica in Taipei and Princeton University Library, of which 3,613 Tangut texts have been digitized.[28]

In 2010 the Ningxia Academy of Social Sciences started to publish a quarterly journal entitled Tangut Research (Chinese: 西夏研究; pinyin: Xīxià Yánjiū), which is the first regular academic journal devoted exclusively to Tangut studies.[29]

In 2016 a set of 6,125 Tangut characters and 755 Tangut components were encoded in the Unicode Standard version 9.0, which has enabled the display of Tangut text on the internet, and facilitated the digitalization and textual analysis of Tangut documents.[30]

-

Han Xiaomang

-

Lin Ying-chin

-

Sun Bojun

-

Kirill Solonin

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h Nie, Hongyin (1993). "Tangutology During the Past Decades". Monumenta Serica. 41: 329–347. ISSN 0254-9948. Archived from the original on 2011-07-24.

- ^ a b Kessler, Adam T. (2012). Song Blue and White Porcelain on the Silk Road. Volume 27 of Studies in Asian Art and Archaeology. Brill. p. 21. ISBN 9789004218598.

- ^ Dunnell, Ruth (1992). "The Hsia Origins of the Yüan Institution of Imperial Preceptor". Asia Major. 3rd series. 5: 85–111.

- ^ a b Ikeda, Takumi (2006). "Exploring the Mu-nya people and their language". Zinbun (39): 19–147.

- ^ Bushell, S.W. (Oct 1899). "The Tangut script in the Nank'ou Pass". The China Review. 24 (2): 65–68.

- ^ Bushell, S.W. (1895–1896). "The Hsi Hsia Dynasty of Tangut, their Money and Peculiar Script". Journal of the North China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 30: 142–160.

- ^ Nishida, Tatsuo (1966). A Study of Hsi-Hsia Language. Tokyo: The Zauho Press. p. 519.

- ^ Pelliot, Paul (1932). "Livres reçus: N. A. Nevskii, Očerk istorii tangutovedenya ("Histoire des études sur le si-hia")". T'oung Pao. 2. 29 (1): 226–229.

- ^ Morisse, G. (1904). "Contribution preliminaire à l'étude de l'écriture et de la langue Si-hia". Mémoires présentés par divers savants à l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 1. 11 (2): 313–379. doi:10.3406/mesav.1904.1090.

- ^ a b Kychanov, Evgenij Ivanovich (1996–2000). "preface". 俄藏黑水城文献 [Heishuicheng Manuscripts Collected in the St.Petersburg Branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences]. Vol. 1. Shanghai Guji Chubanshe. ISBN 7-5325-2036-6.

- ^ Nishida, Tatsuo (2005). "Editor's Preface". Xixia Version of the Lotus Sutra from the Collection of the St. Petersburg Branch of the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences (PDF). Soka Gakkai. p. 167 ).

- ^ a b c Kychanov, Ye. I. (5 November 2005). "Tangut Studies at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts". Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ^ Clauson, Gerard (1964). "The future of Tangut (Hsi Hsia) studies" (PDF). Asia Major. n.s. 11 (1): 54–77.

- ^ Gerard Clauson's Skeleton Tangut (Hsi Hsia) Dictionary: A facsimile edition. With an introduction by Imre Galambos. With Editorial notes and an Index by Andrew West. Prepared for publication by Michael Everson. Portlaoise: Evertype. ISBN 978-1-78201-167-5.

- ^ a b c Grinstead, Eric (December 1974). "Hsi-Hsia: News of the Field" (PDF). Sung Studies Newsletter. 10: 38–42.

- ^ Nishida, Tatsuo (1986). "西夏語『月々楽詩』の研究" [Study of the Tangut language 'Poem on Pleasure of Every Month']. 京都大学文学部紀要 (Memoirs of the Faculty of Letters Kyoto University). 25: 1–116.

- ^ van Driem, George (2001). Languages of the Himalayas. Vol. 1. BRILL. p. 456. ISBN 978-90-04-12062-4.

- ^ Shi, Jinbo (2012). "The Pillar of Tangutology: E.I. Kychanov's Contribution and Influence on Tangut Studies". In Popova, Irina (ed.). Тангуты в Центральной Азии: сборник статей в честь 80-летия проф. Е.И.Кычанова [Tanguts in Central Asia: a collection of articles marking the 80th anniversary of Prof. E. I. Kychanov]. Oriental Literature. pp. 469–480. ISBN 978-5-02-036505-6.

- ^ He Lulu 贺璐璐 (4 May 2008). 古塔废墟下的宝藏 [Precious sutras beneath the ruins of an ancient pagoda] (in Chinese). China National Radio. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ^ Shi Jinbo (史金波) (1997). 现存世界上最早的木活字:西夏活字印本考 [The earliest surviving wooden movable type in the world: A study of Tangut books printed with movable type]. 北京图书馆馆刊 (Journal of Beijing Library) (in Chinese) (1): 67–80. ISSN 1006-9666.

- ^ a b Gaowa, Saren (21 June 2007). "A Review of Tangut Buddhism, Art and Textual Studies". International Dunhuang Project. Retrieved 2012-10-25.

- ^ McKay, Alex. "Buddhism and State Foundation in Eleventh Century Xia". International Institute for Asian Studies. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ^ Kepping, Ksenia (2003). "Zhuge Liang's «The general's garden» in the Mi-Nia translation". Last Works and Documents (PDF). St. Petersburg. pp. 13–24.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Grinstead, Eric (October 1972). "The Tangut Tripitaka, Some Background Notes" (PDF). Sung Studies Newsletter (6): 19–23.

- ^ a b Cook, Richard. "Tangut (Xīxià) Orthography and Unicode : Research notes toward a Unicode encoding of Tangut". Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ^ "Petra Kappert Fellow". Centre for the Study of Manuscript Cultures at the University of Hamburg. Retrieved 2012-10-26.

- ^ Mair, Victor H. (2010–2011). "The Impact of IDP on Dunhuang Studies". IDP News (36–37). International Dunhuang Project: 4–5. ISSN 1354-5914.

- ^ "IDP Statistics". International Dunhuang Project. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- ^ 西夏研究 [Tangut Research] (in Chinese). Ningxia Academy of Social Sciences. Retrieved 2012-10-23.

- ^ "Unicode 9.0.0". The Unicode Standard. Retrieved 30 September 2021.

External links

[edit]- Bibliography of Tangut Studies

- A Review of Tangut Buddhism, Art and Textual Studies by Saren Gaowa

- Tangutology During the Past Decades by Nie Hongyin

- Tangut Studies at the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts by E. I. Kychanov