Lexical hypothesis

In personality psychology, the lexical hypothesis[1] (also known as the fundamental lexical hypothesis,[2] lexical approach,[3] or sedimentation hypothesis[4]) generally includes two postulates:

1. Those personality characteristics that are important to a group of people will eventually become a part of that group's language.[5]

and that therefore:

2. More important personality characteristics are more likely to be encoded into language as a single word.[6][7][8]

With origins during the late 19th century, use of the lexical hypothesis began to flourish in English and German psychology during the early 20th century.[4] The lexical hypothesis is a major basis of the study of the Big Five personality traits,[9] the HEXACO model of personality structure[10] and the 16PF Questionnaire and has been used to study the structure of personality traits in a number of cultural and linguistic settings.[11]

History

[edit]Early estimates

[edit]

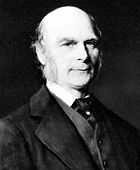

Sir Francis Galton was one of the first scientists to apply the lexical hypothesis to the study of personality,[4] stating:

I tried to gain an idea of the number of the more conspicuous aspects of the character by counting in an appropriate dictionary the words used to express them... I examined many pages of its index here and there as samples of the whole, and estimated that it contained fully one thousand words expressive of character, each of which has a separate shade of meaning, while each shares a large part of its meaning with some of the rest.[12]: 181

— Francis Galton, Measurement of Character, 1884

Despite Galton's early ventures into the lexical study of personality, more than two decades passed before English-language scholars continued his work. A 1910 study by George E. Partridge listed approximately 750 English adjectives used to describe mental states,[13] while a 1926 study of Webster's New International Dictionary by M. L. Perkins provided an estimate of 3,000 such terms.[14] These early explorations and estimates were not limited to the English-speaking world, with philosopher and psychologist Ludwig Klages stating in 1929 that the German language contains approximately 4,000 words to describe inner states.[15]

Psycholexical studies

[edit]Allport & Odbert

[edit]

Nearly half a century after Galton first investigated the lexical hypothesis, Franziska Baumgarten published the first psycholexical classification of personality-descriptive terms. Using dictionaries and characterology publications, Baumgarten identified 1,093 separate terms in the German language used for the description of personality and mental states.[16] Although this number is similar in size to the German and English estimates offered by earlier researchers, Gordon Allport and Henry S. Odbert revealed this to be a severe underestimate in a 1936 study. Similar to the earlier work of M. L. Perkins, they used Webster's New International Dictionary as their source. From this list of approximately 400,000 words, Allport and Odbert identified 17,953 unique terms used to describe personality or behavior.[16]

This is one of the most influential psycholexical studies in the history of trait psychology.[4] Not only was it the longest, most exhaustive list of personality-descriptive words at the time,[4] it was also one of the earliest attempts at classifying English-language terms with the use of psychological principles. Using their list of nearly 18,000 terms, Allport and Odbert separated these into four categories or "columns":[16]

- Column I: This group contains 4,504 terms that describe or are related to personality traits. Being the most important of the four columns to Allport and Odbert and future psychologists,[4] its terms most closely relate to those used by modern personality psychologists (e.g., aggressive, introverted, sociable). Allport and Odbert suggested that this column represented a minimum rather than final list of trait terms. Because of this, they recommended that other researchers consult the remaining three columns in their studies.[16]

- Column II: In contrast with the more stable dispositions described by terms in Column I, this group includes terms describing present states, attitudes, emotions, and moods (e.g., rejoicing, frantic). As a result of this emphasis of temporary states, present participles represent the majority of the 4,541 terms in Column II.

- Column III: The largest of the four groups, Column III contains 5,226 words related to social evaluations of an individual person's character (e.g., worthy, insignificant). Unlike the previous two columns, this group does not refer to internal psychological attributes of a person. As such, Allport and Odbert acknowledged that Column III did not meet their definition of trait-related terms. Predating the person-situation debate by more than 30 years,[17] Allport and Odbert included this group to appease researchers of social psychology, sociology, and ethics.[16]

- Column IV: The last of Allport and Odbert's four columns contained 3,682 words. Termed the "miscellaneous column" by the authors, Column IV contains important personality-descriptive terms that did not seem appropriate for the other three columns. Allport and Odbert offered potential subgroups for terms describing behaviors (e.g., pampered, crazed), physical qualities associated with psychological traits (e.g., lean, roly-poly), and talents or abilities (e.g., gifted, prolific). However, they noted that these subdivisions were not necessarily accurate, as: (i) innumerable subgroups were possible, (ii) these subgroups would not incorporate all of the miscellaneous terms, and (iii) further editing might reveal that these terms could be used for the other three columns.[16]

Allport and Odbert did not present these four columns as representing orthogonal concepts. Many of their nearly 18,000 terms could have been classified differently or put into multiple categories, particularly those in Columns I and II. Although the authors attempted to remedy this with the aid of three other editors, the average degree of agreement between these independent reviewers was approximately 47%. Noting that each outside reviewer seemed to have a preferred column, the authors decided to present the classifications performed by Odbert. Rather than try to rationalize this decision, Allport and Odbert presented the results of their study as somewhat arbitrary and unfinished.[16]

Warren Norman

[edit]Throughout the 1940s, researchers such as Raymond Cattell[5] and Donald Fiske[18] used factor analysis to explore the more general structure of the trait terms in Allport and Odbert's Column I. Rather than rely on the factors obtained by these researchers,[4] Warren Norman performed an independent analysis of Allport and Odbert's terms in 1963.[19] Despite finding a five-factor structure similar to Fiske's, Norman decided to use Allport and Odbert's original list to create a more precise and better-structured taxonomy of terms.[20] Using the 1961 edition of Webster's International Dictionary, Norman added relevant terms and removed those from Allport and Odbert's list that were no longer in use. This resulted in a source list of approximately 40,000 potential trait-descriptive terms. Using this list, Norman then removed terms that were deemed archaic or obsolete, solely evaluative, overly obscure, dialect-specific, loosely related to personality, and purely physical. By doing so, Norman reduced his original list to 2,797 unique trait-descriptive terms.[20] Norman's work would eventually serve as the basis for Dean Peabody and Lewis Goldberg's explorations of the "Big Five" personality traits.[21][22][23]

Juri Apresjan and the Moscow Semantic School

[edit]During the 1970s, Juri Apresjan, a founder of the Moscow Semantic School, developed the systemic, or systematic, method of lexicography which utilizes the concept of the language picture of the world. This concept is also termed the naive picture of the world in order to stress the non-scientific description of the world which is found in natural language.[24] In his book "Systematic Lexicography", which was published in English in 2000, J.D.Apresjan puts forward the idea of building dictionaries on the basis of "reconstructing the so-called naive picture of the world, or the "world-view", underlying the partly universal and partly language specific pattern of conceptualizations inherent in any natural language".[25] In his opinion, the general world-view can be fragmented into different more local pictures of reality, such as naive geometry, naive physics, naive psychology, and so forth. In particular, one chapter of the book Apresjan allots to the description of lexicographic reconstruction of the language picture of the human being in the Russian language.[26] Later, Apresjan's work was the basis for Sergey Golubkov's further attempts to build "the language personality theory"[27][28][29] which would be different from other lexically-based personality theories (e.g. by Allport, Cattell, Eysenck, etc.) due to its meronomic (partonomic) nature versus the taxonomic nature of the previously mentioned personality theories.[30]

Psycholexical studies of values

[edit]In addition to research on personality, the psycholexical method has also been applied to the study of values in multiple languages,[31][32] providing a contrast with theory-driven approaches such as Schwartz's Theory of Basic Human Values.[33][34]

Similar concepts

[edit]Philosophy

[edit]Concepts similar to the lexical hypothesis are basic to ordinary language philosophy.[35] Similar to the use of the lexical hypothesis to understand personality, ordinary language philosophers propose that philosophical problems can be solved or better understood by an examination of everyday language. In his essay "A Plea for Excuses," J. L. Austin cited three main justifications for this method: words are tools, words are not only facts or objects, and commonly used words "embod[y] all the distinctions men have found worth drawing...we are using a sharpened awareness of words to sharpen our perception of, though not as the final arbiter of, the phenomena".[36]: 182

Criticism

[edit]Despite its widespread use for the study of personality, the lexical hypothesis has been challenged for a number of reasons. The following list describes some of the major critiques of the lexical hypothesis and personality models based on psycholexical studies.[8][6][35][37]

- The use of verbal descriptors as material for analysis brings a pro-social bias of language into the resulting models.[38][39][40] Experiments using the lexical hypothesis indeed demonstrated that the use of lexical material skews the resulting dimensionality according to a sociability bias of language and a negativity bias of emotionality, grouping all evaluations around these two dimensions.[38] This means that the two largest dimensions in the Big Five model of personality (i.e., Extraversion and Neuroticism) might be just an artifact of the lexical method that this model employed.

- Many traits of psychological importance are too complex to be encoded into single terms or used in everyday language.[41] In fact, an entire text may be the only way to accurately capture and reflect some important personality characteristics.[42]

- Laypeople use personality-descriptive terms in an ambiguous manner.[43] Similarly, many of the terms used in psycholexical studies are too ambiguous to be useful in a psychological context.[44]

- The lexical hypothesis relies on terms that were not developed by experts.[37] As such, any models developed with the lexical hypothesis represent lay perceptions rather than expert psychological knowledge.[43]

- Language accounts for a minority of communication and is inadequate to describe much of human experience.[45]

- The mechanisms that resulted in the development of personality lexicons are poorly understood.[6]

- Personality-descriptive terms change over time and differ in meaning across dialects, languages, and cultures.[6]

- The methods used to test the lexical hypothesis are unscientific.[43][46]

- Personality-descriptive language is too general to be represented by a single word class,[47] yet psycholexical studies of personality largely rely on adjectives.[35][48]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Crowne, D. P. (2007). Personality Theory. Don Mills, ON, Canada: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-542218-4.

- ^ Goldberg, L. R. (December 1990). "An alternative "description of personality": The Big-Five factor structure". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 59 (6): 1216–1229. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.6.1216. PMID 2283588. S2CID 9034636.

- ^ Carducci, B. J. (2009). The Psychology of Personality: Second Edition. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-3635-8.

- ^ a b c d e f g Caprara, G. V.; Cervone, D. (2000). Personality: Determinants, Dynamics, and Potentials. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58310-7.

- ^ a b Cattell, R.B. (1943). "The description of personality: basic traits resolved into clusters". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 38 (4): 476–506. doi:10.1037/h0054116.

- ^ a b c d John, O. P.; Angleitner, A.; Ostendorf, F. (1988). "The lexical approach to personality: A historical review of trait taxonomic research". European Journal of Personality. 2 (3): 171–203. doi:10.1002/per.2410020302. S2CID 15299845. Archived from the original on 26 October 2014.

- ^ Miller, George A (1996). The science of words. New York: Scientific American Library. ISBN 978-0-7167-5027-7.

- ^ a b Ashton, M. C.; Lee, K. (2004). "A defence of the lexical approach to the study of personality structure" (PDF). European Journal of Personality. 19: 5–24. doi:10.1002/per.541. S2CID 145576560. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 March 2012.

- ^ Goldberg, Lewis (1993). "The structure of phenotypic personality traits". American Psychologist. 48 (1): 26–34. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.48.1.26. PMID 8427480. S2CID 20595956.

- ^ Ashton, Michael C.; Lee, Kibeom; Perugini, Marco; Szarota, Piotr; de Vries, Reinout E.; Di Blas, Lisa; Boies, Kathleen; De Raad, Boele (2004). "A Six-Factor Structure of Personality-Descriptive Adjectives: Solutions From Psycholexical Studies in Seven Languages". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 86 (2): 356–366. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.86.2.356. ISSN 0022-3514. PMID 14769090.

- ^ John, O. P.; Robins, R. W.; Pervin, L. A. (2008). Handbook of Personality: Theory and Research, Third Edition. New York: The Guilford Press. pp. 114–158. ISBN 978-1-59385-836-0.

- ^ Galton, F. (1884). "Measurement of Character" (PDF). Fortnightly Review. 36: 179–185.

- ^ Partridge, G. E. (1910). An Outline of Individual Study. New York: Sturgis & Walton. pp. 106–111.

- ^ Perkins, M. L. (1926). "The teaching of ideals and the development of the traits of character and personality" (PDF). Proceedings of the Oklahoma Academy of Science. 6 (2): 344–347. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 27 March 2012.

- ^ Klages, L. (1929). The Science of Character. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- ^ a b c d e f g Allport, G. W.; Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait-names: A psycho-lexical study. Albany, NY: Psychological Review Company.

- ^ Epstein, S.; O'Brien, E. J. (November 1985). "The person-situation debate in historical and current perspective". Psychological Bulletin. 98 (3): 513–537. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.98.3.513. PMID 4080897.

- ^ Fiske, D. W. (July 1949). "Consistency of the factorial structures of personality ratings from different sources". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 44 (3): 329–344. doi:10.1037/h0057198. hdl:2027.42/179031. PMID 18146776.

- ^ Norman, W. T. (June 1963). "Toward an adequate taxonomy of personality attributes: Replicated factor structure in peer nomination personality ratings". Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology. 66 (6): 574–583. doi:10.1037/h0040291. PMID 13938947.

- ^ a b Norman, W. T. (1967). 2800 personality trait descriptors: Normative operating characteristics for a university population. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Dept. of Psychology.

- ^ Fiske, D. W. (1981). Problems with Language Imprecision: New Directions for Methodology of Social and Behavioral Science. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. pp. 43–65.

- ^ Peabody, D.; Goldberg, L. R. (September 1989). "Some determinants of factor structures from personality-trait descriptors". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 57 (3): 552–567. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.3.552. PMID 2778639. S2CID 19459419.

- ^ Goldberg, L. R. (December 1990). "An alternative "description of personality": The Big-Five factor structure". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 59 (6): 1216–1229. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.59.6.1216. PMID 2283588. S2CID 9034636.

- ^ Apresi͡an, I͡Uriĭ Derenikovich (2000). Systematic Lexicography. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-823780-8.

- ^ "Apresjan J. (1992). Systemic Lexicography. In Euralex-92 Proceedings (part 1). p.4" (PDF). Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ^ Apresi͡an, I͡Uriĭ Derenikovich (2000). "The Picture of Man as Reconstructed from Linguistic Data: An Attempt at a Systematic Description". Systematic Lexicography. Oxford University Press. pp. 101–143. ISBN 978-0-19-823780-8.

- ^ "Golubkov's Language Personality Theory". webspace.ship.edu.

- ^ Golubkov S.V. (2002). "The language personality theory: An integrative approach to personality on the basis of its language phenomenology". Social Behavior and Personality. 30 (6): 571–578. doi:10.2224/sbp.2002.30.6.571.

- ^ "PsychNews 5(1)". userpage.fu-berlin.de.

- ^ Golubkov S.V. (2002). "The language personality theory: An integrative approach to personalityon the basis of its language phenomenology". Social Behavior and Personality. 30 (6): 573. doi:10.2224/sbp.2002.30.6.571.

- ^ De Raad, Boele; Van Oudenhoven, Jan Pieter (January 2011). "A psycholexical study of virtues in the Dutch language, and relations between virtues and personality". European Journal of Personality. 25 (1): 43–52. doi:10.1002/per.777. S2CID 227275239.

- ^ De Raad, Boele; Morales-Vives, Fabia; Barelds, Dick P. H.; Van Oudenhoven, Jan Pieter; Renner, Walter; Timmerman, Marieke E. (28 July 2016). "Values in a Cross-Cultural Triangle" (PDF). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 47 (8): 1053–1075. doi:10.1177/0022022116659698. S2CID 151792686.

- ^ Schwartz, Shalom H. (15 March 2017). "Theory-Driven Versus Lexical Approaches to Value Structures". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 48 (3): 439–443. doi:10.1177/0022022117690452. S2CID 151514308.

- ^ De Raad, Boele; Timmerman, Marieke E.; Morales-Vives, Fabia; Renner, Walter; Barelds, Dick P. H.; Pieter Van Oudenhoven, Jan (15 March 2017). "The Psycho-Lexical Approach in Exploring the Field of Values". Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 48 (3): 444–451. doi:10.1177/0022022117692677. PMC 5414899. PMID 28502995.

- ^ a b c De Raad, B. (June 1998). "Five big, Big Five issues: Rationale, content, structure, status, and crosscultural assessment". European Psychologist. 3 (2): 113–124. doi:10.1027/1016-9040.3.2.113.

- ^ Austin, J. L. (1970). Philosophical Papers. London: Oxford University Press. pp. 175–204.

- ^ a b Dumont, F. (2010). A History of Personality Psychology: Theory, Science, and Research from Hellenism to the Twenty-first Century. New York: Cambridge University Press. pp. 149–182. ISBN 978-0-521-11632-9.

- ^ a b Trofimova, I. N. (2014). "Observer bias: an interaction of temperament traits with biases in the semantic perception of lexical material". PLOS ONE. 9 (1): e85677. Bibcode:2014PLoSO...985677T. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0085677. PMC 3903487. PMID 24475048.

- ^ Trofimova, I.; Robbins, TW; W., Sulis; J., Uher (2018). "Taxonomies of psychological individual differences: biological perspectives on millennia-long challenges". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, Biological Sciences. 373 (1744). doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0152. PMC 5832678. PMID 29483338.

- ^ Trofimova, I; et al. (2022). "What's next for the neurobiology of temperament, personality and psychopathology?". Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 45: 101143. doi:10.1016/j.cobeha.2022.101143. S2CID 248817462.

- ^ Block, J. (March 1995). "A contrarian view of the five-factor approach to personality description". Psychological Bulletin. 117 (2): 187–215. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.117.2.187. PMID 7724687.

- ^ McCrae, R. R. (November 1994). "Openness to experience: Expanding the boundaries of Factor V". European Journal of Personality. 8 (4): 251–272. doi:10.1002/per.2410080404. S2CID 144576220.

- ^ a b c Westen, D. (September 1996). "A model and a method for uncovering the nomothetic from the idiographic: An alternative to the Five-Factor Model" (PDF). Journal of Research in Personality. 30 (3): 400–413. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.523.5477. doi:10.1006/jrpe.1996.0028. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 May 2012.

- ^ Bromley, D. B. (1977). Personality Description in Ordinary Language. London: Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-99443-5.

- ^ Mehrabian, A. (1971). Silent Messages. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. ISBN 978-0-534-00910-6.

- ^ Shadel, W. G.; Cervone, D. (December 1993). "The Big Five versus nobody?". American Psychologist. 48 (12): 1300–1302. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.48.12.1300.

- ^ De Raad, B.; Mulder, E.; Kloosterman, K.; Hofstee, W. K. B. (June 1988). "Personality-descriptive verbs". European Journal of Personality. 2 (2): 81–96. doi:10.1002/per.2410020204. S2CID 146758458.

- ^ Eysenck, Hans Jurgen (1993). "The structure of phenoytypic personality traits: Comment". The American Psychologist. 48 (12): 1299–1300. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.48.12.1299.b.