Les Chants de Maldoror

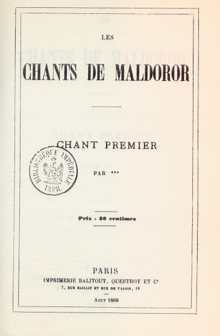

Cover of the first French edition | |

| Author | Comte de Lautréamont (Isidore Lucien Ducasse) |

|---|---|

| Original title | Les Chants de Maldoror |

| Translator |

|

| Language | French |

| Genre | Poetic novel |

| Publisher | Gustave Balitout, Questroy et Cie. (original) |

Publication date | 1868–69 1874 (complete edition, with new cover) |

| Publication place | France |

| Media type | |

| OCLC | 457272491 |

Original text | Les Chants de Maldoror at French Wikisource |

Les Chants de Maldoror (The Songs of Maldoror) is a French poetic novel, or a long prose poem. It was written and published between 1868 and 1869 by the Comte de Lautréamont, the nom de plume of the Uruguayan-born French writer Isidore Lucien Ducasse.[1] The work concerns the misanthropic, misotheistic character of Maldoror, a figure of evil who has renounced conventional morality.

Although obscure at the time of its initial publication, Maldoror was rediscovered and championed by the Surrealist artists during the early twentieth century.[2] The work's transgressive, violent, and absurd themes are shared in common with much of Surrealism's output;[3] in particular, Louis Aragon, André Breton, Salvador Dalí, Man Ray, and Philippe Soupault were influenced by the work.[a] Maldoror was itself influenced by earlier gothic literature of the period, including Lord Byron's Manfred, and Charles Maturin's Melmoth the Wanderer.[4]

Synopsis and themes

[edit]Maldoror is a modular work primarily divided into six parts, or cantos; these parts are further subdivided into a total of sixty chapters, or verses.[b] With some exceptions, most chapters consist of a single, lengthy paragraph.[c] The text often employs very long, unconventional and confusing sentences which, together with the dearth of paragraph breaks, may suggest a stream of consciousness, or automatic writing.[6] Over the course of the narrative, there is often a first-person narrator, although some areas of the work instead employ a third-person narrative. The book's central character is Maldoror, a figure of evil who is sometimes directly involved in a chapter's events, or else revealed to be watching at a distance. Depending on the context of narrative voice in a given place, the first-person narrator may be taken to be Maldoror himself, or sometimes not. The confusion between narrator and character may also suggest an unreliable narrator.[7]

Several of the parts begin with opening chapters in which the narrator directly addresses the reader, taunts the reader, or simply recounts the work thus far. For example, an early passage[d] warns the reader not to continue:

"It is not right that everyone should read the pages which follow; only a few will be able to savour this bitter fruit with impunity. Consequently, shrinking soul, turn on your heels and go back before penetrating further into such uncharted, perilous wastelands."

— Maldoror, Part I, Chapter 1.[8]

Apart from these opening segments, each chapter is typically an isolated, often surreal episode, which does not seem at first to be directly related to the surrounding material. For example, in one chapter,[e] a funeral procession takes a boy to his grave and buries him, with the officiant condemning Maldoror; the following chapter[f] instead presents a story of a sleeping man (seemingly Maldoror) who is repeatedly bitten by a tarantula which emerges from the corner of his room, every night. Another strange episode occurs in an early chapter: the narrator encounters a giant glow-worm which commands him to kill a woman, who symbolizes prostitution. In defiance, the narrator instead hurls a large stone onto the glow-worm, killing it:

"The shining worm, to me: 'You, take a stone and kill her.' 'Why?' I asked. And it said to me: 'Beware, look to your safety, for you are the weaker and I the stronger. Her name is Prostitution.' With tears in my eyes and my heart full of rage, I felt an unknown strength rising within me. I took hold of a huge stone; after many attempts, I managed to lift it as far as my chest. Then, with my arms, I put it on my shoulders. I climbed the mountain until I reached the top: from there, I hurled the stone on to the shining worm, crushing it.

— Maldoror, Part I, Chapter 7.[9]

As the work progresses, certain common themes emerge among the episodes. In particular, there is constant imagery of many kinds of animals, sometimes employed in similes. For example, in one case, Maldoror copulates with a shark, each admiring the others' violent nature, while in another, the narrator has a pleasant dream that he is a hog. These animals are praised precisely for their inhumanity, which fits the work's misanthropic tone:

The swimmer is now in the presence of the female shark he has saved. They look into each other's eyes for some minutes, each astonished to find such ferocity in the other's eyes. They swim around keeping each other in sight, and each one saying to himself: 'I have been mistaken; here is one more evil than I.' Then by common accord they glide towards one another underwater, the female shark using its fins, Maldoror cleaving the waves with his arms; and they hold their breath in deep veneration, each one wishing to gaze for the first time upon the other, his living portrait. When they are three yards apart they suddenly and spontaneously fall upon one another like two lovers and embrace with dignity and gratitude, clasping each other as tenderly as brother and sister. Carnal desire follows this demonstration of friendship.

— Maldoror, Part II, Chapter 13.[10]

I dreamt I had entered the body of a hog, that I could not easily get out again, and that I was wallowing in the filthiest slime. Was it a kind of reward? My dearest wish had been granted; I no longer belonged to mankind.

— Maldoror, Part IV, Chapter 6.[11]

Another recurring theme among certain of the chapters is an urban–rural dichotomy. Some episodes take place in a town or city, while others occur at a deserted shore, with only a few actors. The juxtaposition of urban city scenes and rural shoreline scenes may be inspired by Ducasse's time in Paris and Montevideo, respectively. Other pervasive themes include homosexuality, blasphemy, and violent crime, often directed against children.

Maldoror's sixth and final part instead employs a definite change in style, while retaining most of the themes already developed. The final part (specifically its last eight chapters), intended as a "little novel" which parodies the forms of the nineteenth-century novel,[12] presents a linear story using simpler language. In it, a schoolboy named Mervyn returns home to his well-to-do family in Paris, unaware that Maldoror had been stalking him. Maldoror writes Mervyn a love letter, requesting to meet, and Mervyn replies and accepts. Upon their meeting, Maldoror forces Mervyn into a sack, and beats his body against the side of a bridge, ultimately flinging the sack onto the dome of the Panthéon. This final, violent episode has been interpreted as a killing of the traditional novel form, in favor of Maldoror's experimental writing.[13]

Source material

[edit]Some of the material was copied from encyclopedias by Buffon, and from his collaborator Guéneau de Monbeillard, through Encyclopédie d'histoire naturelle, reprints made by a nineteenth-century compiler, Jean-Charles Chenu,[14] such as the following section in Canto 5, Strophe 2:[15]

I knew that the family of the pelicanides consists of four distinct genera: the gannet, the pelican, the cormorant, and the frigate-bird. The greyish shape which appeared before me was not a gannet. The plastic block I perceived was not a frigate-bird. The crystallized flesh I observed was not a cormorant. I saw him now, the man whose encephalon was entirely devoid of an annular protuberance!

Je savais que la famille des pélécaninés comprend quatre genres distincts : le fou, le pélican, le cormoran, la frégate. La forme grisâtre qui m’apparaissait n’était pas un fou. Le bloc plastique que j’apercevais n’était pas une frégate. La chair cristallisée que j’observais n’était pas un cormoran. Je le voyais maintenant, l’homme à l’encéphale dépourvu de protubérance annulaire !

Here, "annular protuberance" means the pons varolii, which according to the encyclopedia is not found in birds, thus "the man whose encephalon was entirely devoid of an annular protuberance" is a human who has a bird-brain.

Publication

[edit]The first canto of Maldoror was originally published anonymously on behalf of the author in the autumn of 1868. Printed in August by the publisher Gustave Balitout, it was then distributed in Paris that November. The first canto subsequently featured in a collection of poetry by Évariste Carrance called Les Parfums de l'âme in Bourdeaux in 1869.

The complete work, which consists of six cantos and is written under the pseudonym "Comte de Lautréamont", was printed in Belgium August 1869. The editor of the latter, Albert Lacroix, denied any association with the work and refused to put it on sale for fear of the legal proceedings (this was in part because the author had not paid the 12,000 francs required for the full print run).

Isidore Ducasse published only two other works, this time without a pseudonym. In 1870, shortly before his death the pamphlets Poésies I and Poésies II were sold at a local bookseller, Gabrie. The complete work of Maldoror was never published in the Ducasse's lifetime. In 1874, the stock of the original edition was purchased by J.B. Rozez in Belgium and sold under a new cover. In 1885, Max Waller, director of the Jeune Belgique, published an excerpt prefaced with an introduction penned by the latter.[16]

Influence

[edit]Les Chants de Maldoror is considered to have been a major influence upon French Symbolism, Dada, and Surrealism; editions of the book have been illustrated by Odilon Redon,[17] Salvador Dalí,[18] and René Magritte.[19][20] Italian painter Amedeo Modigliani was known to keep a copy of Maldoror available while traveling in the Montparnasse, sometimes quoting from it.[21] Outsider artist Unica Zürn's literary work The Man of Jasmine was influenced by Maldoror;[22] likewise, William T. Vollmann was influenced by the work.[23]

Maldoror was followed by Poésies, Ducasse's other, minor surviving work, a short work of literary criticism, or poetics. In contrast to Maldoror, Poésies has a far more positive and humanistic tone, and so may be interpreted as a response to the former.

Ducasse admitted to being inspired by Adam Mickiewicz and the form of "The Great Improvisation" from the third part of the Polish bard's Forefathers' Eve.[24]

Yukio Mishima employed the same themes and even quoted sections from the work in his short story "Raisin Bread,[25]" with the main character, Jack, reading the work in his city apartment and quoting the lines as he thinks back on the secluded seaside outing with friends he went to the previous night. The party described includes multiple animals, reoccurring violence & sexual tension similarly to the referenced work itself.

Maldoror is quoted by Argentine author Julio Cortázar in his short story "The Other Heaven."[26]

A theatrical adaptation titled "Maldoror" was co-produced by the La MaMa Experimental Theatre Club and the Mickery Theatre (of Amsterdam), and performed by the Camera Obscura experimental theatre company at La MaMa in the East Village of New York City in 1974.[27] The text for the production was written by Camera Obscura and Andy Wolk, with design and direction by Franz Marijnen.[28] "Maldoror" also went on tour in Europe in 1974.[29]

Maldoror and Ducasse were an inspiration for early music by Current 93, such as the album Live at Bar Maldoror (1985).

Group 180, a Hungarian ensemble released an album in 1989 called The Songs of Maldoror composed by László Melis.

Danish composer Ejnar Kanding (b. 1965) composed a piece in 1997–98 for bass clarinet and live electronics inspired by Les Chants de Maldoror. It was developed in a version for bass clarinet, percussion and live electronics in 2000 with the title Sepulcro Movible.

American composer Daniel Felsenfeld created a piece in 2003 for oboe, flute, piano and narratrix called ‘’From Maldoror’’ eventually rescored for clarinet, flute, piano and narrator at the behest of the Parhelion Trio, with the composer himself often taking the narrator's part.

English translations

[edit]- Rodker, John (translator). The Lay of Maldoror (1924).

- Wernham, Guy (translator). Maldoror (1943). ISBN 0-8112-0082-5

- Knight, Paul (translator). Maldoror and Poems (1978). ISBN 0-14-044342-8

- Lykiard, Alexis (translator). Maldoror and the Complete Works (1994). ISBN 1-878972-12-X

- Dent, R. J., (translator). The Songs of Maldoror (illustrated by Salvador Dalí) (2012). ISBN 978-0-9820464-8-7

- O'Keefe, Gavin L., (translator). The Dirges of Maldoror (illustrated by Gavin L. O'Keefe) (2018). ISBN 978-1-60543-954-9

Notes

[edit]- ^ McCorristine's article specifically identifies Soupault as having discovered a copy of the book in the mathematics section of a bookstore, and at almost the same time, Breton and Aragon became aware of Maldoror: "Revelation, illumination, and epiphany were keywords in de Chirico’s metaphysical aesthetics, and these same poetic sensibilities featured strongly in the ‘discovery’ of Lautréamont, for both Soupault and Aragon independently encountered Maldoror quite ‘by chance’ on the Boulevard Raspail in 1917: Aragon came across the ‘Chant Premier’ quite by accident via an old copy of the symbolist review Vers et Prose published in 1913. What is certain is that Aragon, Breton, and Soupault quickly shared with each other their fascination with Maldoror, and Breton added its mysterious author to one of the early influence-lists that he would frequently compile throughout his career in Surrealism. This collective encounter of ‘the three musketeers’ with Lautréamont, and the "influence déterminante" that his work provided, can be justifiably described as the beginning of the nascent Surrealist movement." (39). Despite this, McCorristine also indicates that Man Ray and a few others were aware of the work (c. 1914) prior to the Surrealist championing. (37)

- ^ Parts one through six consist of fourteen, sixteen, five, eight, seven, and ten chapters, respectively.

- ^ See for example the original French text at Gutenberg.[5]

- ^ All direct quotations in this article derive from Knight's translation, unless otherwise noted.

- ^ Part V, Chapter 6.

- ^ Part V, Chapter 7.

References

[edit]- ^ Comte de Lautréamont (1978). Maldoror and Poems. Translated by Knight, Paul. New York: Penguin. pp. 7–10. ISBN 978-0-14-044342-4.

- ^ McCorristine, Shane (January 2009). "Lautréamont and the Haunting of Surrealism". academia.edu: 36–41.

- ^ Gascoyne, David (1935). A Short Survey of Surrealism. Psychology Press. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-7146-2262-0. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Knight, pp. 16-19.

- ^ Comte de Lautréamont. "Les Chants de Maldoror". Gutenberg.

- ^ Lemaître, Georges (1986). "The Forerunners". Nineteenth-Century Literature Criticism. 12. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Mathews, Harry (November 2, 1995). "Shark-Shagger". London Review of Books. 17 (21).

- ^ Knight, p. 29.

- ^ Knight, p. 36.

- ^ Knight, pp. 111-112.

- ^ Knight, p. 167.

- ^ Knight, pp. 21–26.

- ^ Knight, p. 21.

- ^ "Le bestiaire de Lautréamont : classement commenté des animaux". Anthropozoologica (in French). 42 (1): 7–18. 2007.

- ^ Hadlock, Philip G. (1998). "Ducasse's Tribal Code: Literary Specificity in the "Poesies" and the "Chants de Maldoror"". South Atlantic Review. 63 (1): 20–34. doi:10.2307/3201389. ISSN 0277-335X. JSTOR 3201389.

- ^ Édition Pléiade Lautréamont-Nouveau, 1970, p. 12.

- ^ "The Lay of Maldoror, Illustrated by Odilon Redon (art object inventory page)". Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- ^ "MoMA - The Collection - Salvador Dalí. Les Chants de Maldoror. 1934". Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Les Chants de Maldoror. With 77 illustrations by René Magritte; Éditions De "La Boétie“, Brussels 1948.

- ^ "Magritte's Maldoror". johncoulthart.com. 18 January 2012.

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey (2014). Modigliani: A Life. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-544-39121-5. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Hubert, Renäe Riese (1994). Magnifying Mirrors: Women, Surrealism, & Partnership. University of Nebraska Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-8032-2370-7. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Bell, Madison Smartt (1993). "Where an Author Might Be Standing". Review of Contemporary Fiction. 13 (2): 39–45. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

- ^ Lautréamont, comte de (1846-1870). (2004). The Songs of Maldoror and Poems. Żurowski, Maciej (1915-2003). Cracow: Mireki. p. 14. ISBN 83-89533-06-5. OCLC 749635076.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Mishima, Yukio (1990). Acts of Worship: Seven Stories. Translated by Bester, John (1st Paperback ed.). Japan: Kodansha International. pp. 13–33. ISBN 0870118242.

- ^ Cortázar, Julio (1973). All Fires the Fire : and other stories. New Directions Publishing. p. 134. ISBN 978-0-8112-2945-6.

- ^ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Production: Maldoror (1974)." Accessed January 25, 2019.

- ^ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Program: "Maldoror" (1974)." Accessed January 25, 2019.

- ^ La MaMa Archives Digital Collections. "Tour: Camera Obscura European Tour (1974)". Accessed January 25, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Les Chants de Maldoror at Project Gutenberg (in French)

Les Chants de Maldoror public domain audiobook at LibriVox (in French)

Les Chants de Maldoror public domain audiobook at LibriVox (in French)