Great ape personhood

Great ape personhood is a movement to extend personhood and some legal protections to the non-human members of the great ape family: bonobos, chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans.[1][2][3]

Advocates include primatologists Jane Goodall and Dawn Prince-Hughes, evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins, philosophers Paola Cavalieri and Peter Singer, and legal scholar Steven Wise.[4][5]

Status

[edit]

On February 28, 2007, the parliament of the Balearic Islands, an autonomous community of Spain, passed the world's first legislation that would effectively grant legal personhood rights to all great apes.[6] On June 25 2008, a parliamentary committee set forth resolutions urging Spain to grant the primates the right to life and liberty. If approved "it will ban harmful experiments on apes and make keeping them for circuses, television commercials, or filming illegal under Spain's penal code."[7]

In 1992, Switzerland amended its constitution to recognize animals as beings and not things.[8] However, in 1999 the Swiss constitution was completely rewritten, and this distinction was removed. A decade later, Germany guaranteed rights to animals in a 2002 constitutional amendment, the first European Union member to do so.[8][9][10]

New Zealand created specific legal protections for five great ape species in 1999.[11] The use of gorillas, chimpanzees and orangutans in research, testing, or teaching is limited to activities intended to benefit the animals or its species. A New Zealand animal protection group later argued the restrictions conferred weak legal rights.[12]

Several European countries including Austria, the Netherlands, and Sweden have completely banned the use of great apes in animal testing.[13] Austria was the first country to ban experimentation on lesser apes. Under EU Directive 2010/63/EU, the entire European Union banned great ape experimentation in 2013.

Argentina granted a captive orangutan basic rights in late 2014.[14]

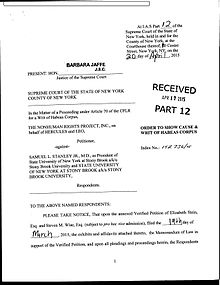

On April 20, 2015, Justice Barbara Jaffe of New York State Supreme Court ordered a writ of habeas corpus to two captive chimpanzees[15][unreliable source] . The next day the ruling was amended to strike the words "writ of habeas corpus".[16][17][18]

Advocacy

[edit]Well-known advocates include primatologist Jane Goodall, who was appointed a goodwill ambassador for the United Nations to fight the bushmeat trade and end ape extinction; Richard Dawkins, former Professor for the Public Understanding of Science at Oxford University; Peter Singer, professor of philosophy at Princeton University; and attorney and former Harvard professor Steven Wise, founder and president of the Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP), whose aim is to use U.S. common law on a state-by-state basis to achieve recognition of legal personhood for great apes and other self-aware, autonomous non-human animals.[4][19][unreliable source]

In December 2013, the NhRP filed three lawsuits on behalf of four chimpanzees being held in captivity in New York State, arguing that they should be recognized as legal persons with the fundamental right to bodily liberty (i.e. not to be held in captivity) and that they are entitled to common law writs of habeas corpus and should be immediately freed and moved to sanctuaries.[20] All three petitions for writs of habeas corpus were denied, allowing for the right to appeal. The NhRP is[when?] appealing all three decisions.[21]

Goodall's longitudinal studies revealed the social and family life of chimps to be similar to those of human beings. Goodall describes them as individuals, and claims they relate to her as an individual member of the clan. Laboratory studies of ape language ability revealed other human traits, as did genetics, and eventually three of the great apes were reclassified as hominids.

Other studies, such as one done by Beran and Evans,[22] indicate other qualities that humans share with non-human primates, namely the ability to self-control. In order for chimpanzees to control their impulsivity, they use self-distraction techniques similar to those that are used by children. Great apes also exhibited ability to plan as well as project "oneself into the future", known as "mental time travel". Such complicated tasks require self-awareness, which great apes appear to possess: "the capacity that contribute to the ability to delay gratification, since a self-aware individual may be able to imagine future states of the self".[23]

The recognition of great ape intelligence, alongside the increasing risk of great ape extinction, has led the animal rights movement to put pressure on nations to recognize apes as having limited rights and being legal "persons." In response, the United Kingdom introduced a ban on research using great apes, although testing on other primates has not been limited.[24]

Writer and lecturer Thomas Rose argues that granting legal rights to non-humans is not a new concept. He points out that in most of the world, "corporations are recognized as legal persons and are granted many of the same rights humans enjoy, the right to sue, to vote, and to freedom of speech."[6] Dawn Prince-Hughes has written that great apes meet the commonly accepted standards for personhood: "self-awareness; comprehension of past, present, and future; the ability to understand complex rules and their consequences on emotional levels; the ability to choose to risk those consequences, a capacity for empathy, and the ability to think abstractly."[25]

Gary Francione questions the concept of granting personhood on the basis of whether the animal is human-like (as some have argued) and believes sentience should be the sole criteria used to determine if an animal should enjoy basic rights. He asserts that several other animals, including mice and rats, should also be granted such rights.[26]

Interpretation

[edit]Depending on the exact wording of any proposed or adopted declaration, personhood for the great apes raises questions concerning protections and obligations under national and international laws including:

- Articles 7–29 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

- The 1954 Convention Relating to the Status of Stateless Persons and 1961 Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness regarding nationality and citizenship for persons

- Provisions 4 and 5 of the Declaration of the Rights of the Child

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Bhagwat, S. B. Foundation of Geology. Global Vision, 2009, pp. 232–235:

- "The Hominidae form a taxonomic family, including four extant genera: humans, chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans."

- ^ Groves, Colin P. "Great Apes: The Conflict of Gene-Pools, Conservation and Personhood" in Emily Rousham, Leonard Freedman, and Rayma Pervan. Perspectives in Human Biology: Humans in the Australasian Region. World Scientific, 1996, p. 31:

- "The recognition that we as a species are not phylogenetically separated from other animals, but are nested within the primate group known as the Great Apes, is no longer controversial. Goodman (1963) proposed on this basis to include the great apes (orangutan, gorilla and chimpanzee) in the family Hominidae, a view revived by Groves (1986) and increasingly adopted since then. Increasingly, too, the vernacular term 'Great Apes' has come to be used as a pure synonym for Hominidae, so that humans are also 'Great Apes.' The only remaining systemic controversy seems to be whether chimpanzees and gorillas together form the sister-group of humans, or chimpanzees and humans together constitute the sister-group of gorillas."

- ^ Karcher, Karen. "The Great Ape Project" in Marc Bekoff (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare. Greenwood, 2009, pp. 185–187:

- "The Great Ape Project (GAP) seeks to extend the scope of three basic moral principles to all members of what the GAP founders call the five great ape species (humans, chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans)."

- ^ a b Goodall, Jane in Paola Cavalieri & Peter Singer (eds.) The Great Ape Project: Equality Beyond Humanity. St Martin's Griffin, 1994. (ISBN 031211818X)

- ^ Motavalli, Jim. "Rights from Wrongs. A Movement to Grant Legal Protection to Animals is Gathering Force", E Magazine, March/April 2003.

- ^ a b Thomas Rose (2 August 2007). "Going ape over human rights". CBC News. Archived from the original on 2010-02-03. Retrieved 26 June 2008.

- ^ "Spanish parliament to extend rights to apes". Reuters. 25 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-11.

- ^ a b "Germany guarantees animal rights in constitution". Associated Press. 2002-05-18. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ "Germany guarantees animal rights". CNN. 21 June 2002. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Kate Connolly (2002-06-22). "German animals given legal rights". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-06-26.[dead link]

- ^ "Animal Welfare Act 1999 No 142 (as at 08 September 2018), Public Act 85 Restrictions on use of non-human hominids – New Zealand Legislation". legislation.govt.nz. Retrieved 2019-07-02.

- ^ "A STEP AT A TIME: NEW ZEALAND'S PROGRESS TOWARD HOMINID RIGHTS" BY ROWAN TAYLOR Archived July 28, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Bundesgesetz, mit dem das Tierversuchsgesetz 1989 über Tierversuche an lebenden Tieren". Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-07-31.

- ^ Giménez, Emiliano (January 4, 2015). "Argentine orangutan granted unprecedented legal rights". edition.cnn.com. CNN Espanol. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "Judge Recognizes Two Chimpanzees as Legal Persons, Grants them Writ of Habeas Corpus". nonhumanrightsproject.org. Nonhuman Rights Project. April 20, 2015. Archived from the original on September 9, 2016. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "Judge Barbara Jaffe's amended court order" (PDF). iapps.courts.state.ny.us. New York Supreme Court. April 21, 2015. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 30, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ "Judge Orders Stony Brook University to Defend Its Custody of 2 Chimps". The New York Times. April 21, 2015. Retrieved April 21, 2015.

- ^ David Kravets Ars Technica (8/3/2015) No habeas corpus; chimps are lab “property”: "Animals, including chimpanzees," judge rules, "are considered property."

- ^ "Nonhuman Rights Project".

- ^ Charles Siebert (23 April 2014). "Should a Chimp Be Able to Sue Its Owner?". New York Times Magazine.

- ^ Robert Gavin (3 October 2014). "Appeals panel to weigh personhood for chimpanzee". Times Union.

- ^ Beran MJ; Evans TA (2006). "Maintenance of delay of gratification by four chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes): the effects of delayed reward visibility, experimenter presence, and extended delay intervals". Behavioural Processes. 73 (3): 315–24. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2006.07.005. PMID 16978800. S2CID 33431269.

- ^ Heilbronner, S.; Platt, M. L. (4 December 2007). "Animal Cognition: Time Flies When Chimps Are Having Fun". Current Biology. 17 (23): R1008–R1010. Bibcode:2007CBio...17R1008H. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.10.012. PMID 18054760. S2CID 296013.

- ^ Alok Jha (2005-12-05). "RSPCA outrage as experiments on animals rise to 2.85m". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-06-26.

- ^ Prince-Hughes, Dawn (1987). Songs of the Gorilla Nation. Harmony. p. 138. ISBN 1-4000-5058-8.

- ^ Francione, Gary (2006). "The Great Ape Project: Not so Great". Retrieved 2010-03-22.