Lefebvre's Charles Town expedition

| Charles Town expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Queen Anne's War | |||||||

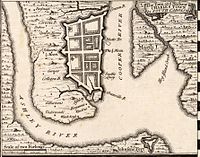

Detail from a 1733 map showing the North American coastline between Charles Town and St. Augustine | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Six privateers 330 French and Spanish regulars 200 Spanish volunteers 50 Indians | Exact number unknown; provincial militia numbered about 900[1] Several provincial naval forces, including impressed merchant ships | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

One ship captured 42 killed over 350 captured | Unknown | ||||||

Lefebvre's Charles Town expedition (September 1706) was a combined French and Spanish attempt under Captain Jacques Lefebvre to capture the capital of the English Province of Carolina, Charles Town, during Queen Anne's War (as the North American theater of the War of the Spanish Succession is sometimes known).

Organized and funded primarily by the French and launched from Havana, Cuba, the expedition reached Charles Town in early September 1706 after stopping at St. Augustine to pick up reinforcements. After a brief encounter with a privateer the Brillant, one of the expedition's six ships, became separated from the rest of the fleet. Troops landed near Charles Town were quickly driven off by militia called out by Governor Nathaniel Johnson when word of the fleet's approach reached the area, and an improvised flotilla commanded by Colonel William Rhett successfully captured the Brillant, which arrived after the other five ships had already sailed away in defeat.

Background

[edit]News of the start of the War of the Spanish Succession had come to southeastern North America in mid-1702, and officials of the English Province of Carolina had acted immediately. After failing in December 1702 to capture St. Augustine, the capital of Spanish Florida, they launched a series of destructive raids against the Spanish-Indian settlements of northern Florida. French authorities in the small settlement at Mobile on the Gulf coast were alarmed by these developments, since, as allies of the Spanish, their territory might also come under attack.[2]

The idea of a combined Franco-Spanish expedition first arose in 1704, when the governor of Florida, José de Zúñiga y la Cerda, discussed the idea with a French naval captain as a means of revenge for the Carolina raids; however, no concrete action came of this discussion.[3] Pierre LeMoyne d'Iberville, the founder of Mobile and an experienced privateer who had previously wrought havoc against English colonial settlements in the Nine Years' War, in 1703 developed a grandiose plan for assaulting Carolina. Using minimal French resources, d'Iberville planned for a small French fleet to join with a large Spanish fleet at Havana, which would then descend on Carolina's capital, then known as Charles Town. The expedition was to be paid for by holding other English colonial communities hostage after destroying Charles Town.[2] It was not until late 1705 that d'Iberville secured permission from King Louis XIV for the expedition.[4] The king provided ships and some troops, but required d'Iberville to bear the upfront cost of outfitting the expedition.[5]

Prelude

[edit]

Two small fleets, one headed by d'Iberville, who was to lead the expedition, left France in January 1706, totalling 12 ships and carrying 600 French troops.[6] They first sailed for the West Indies, where additional troops were recruited at Martinique,[7] and d'Iberville successfully ransacked English-held Nevis.[8] D'Iberville then released part of his squadron, and sailed for Havana.[9] There he attempted to interest Spanish authorities in supporting the expedition, with limited success, due in part to a raging epidemic of yellow fever.[10] In addition to decimating the expedition's troops, Spanish Governor Pedro Álvarez de Villarín died of the disease on July 6, and d'Iberville himself succumbed on July 8.[10] Before he died, d'Iberville handed control of the expedition to Captain Jacques Lefebvre.[11]

Lefebvre sailed from Havana with five ships, carrying about 300 French soldiers under the command of General Arbousset, and 200 Spanish volunteers led by General Esteban de Berroa.[12][13][14] The fleet first made for St. Augustine, where Governor Francisco de Córcoles y Martínez provided a sixth ship, another 30 infantry, and about 50 "Christian Indians" from the Timucua, Apalachee, and Tequassa tribes.[12]

The French fleet sailed from St. Augustine on August 31.[14] During the passage a sloop was spotted, and the Brillant gave chase; she consequently became separated from the rest of the squadron.[12] The sloop was a privateer sent out by Carolina governor Nathaniel Johnson to intercept Spanish supply ships; its captain quickly returned to Charles Town with word of the fleet's movement.[15] The countryside and town, then also suffering the ravages of a yellow fever epidemic, rallied in response to Governor Johnson's calling out of the militia.[12] The exact number of militia mustered is not known; of the non-slave population of 4,000, an estimated 900 men served in the colonial militia.[1] Anticipating that a landing would be attempted on James Island, which guarded the southern approach to the harbor, Johnson posted the militia there under the command of Lieutenant Colonel William Rhett.[14] The northern point of James Island was fortified by Fort Johnson, which housed a few cannon whose range was inadequate to prevent ships from entering the harbor.[16] The militia also improvised a small flotilla of ships, which even included a fire ship.[15]

Attacks

[edit]The Spanish fleet arrived off the harbor bar on September 4 (this date is recorded in contemporary English documents and histories such as Francis Le Jau's diary, as August 24 due to differences between the Julian calendar then in use in the English colonies, and the modern Gregorian calendar).[15] Despite the absence of the Brillant, which carried much of the French force, including "the campaign guns, shovels, spades, shells, and the land commander" (the latter being General Arbousset), Captain Lefebvre and his fleet crossed the bar on September 7, and delivered an ultimatum the next day.[17] He demanded a ransom of 50,000 Spanish pesos, threatening to destroy Charles Town if it was not paid. Governor Johnson contemptuously dismissed the demand as paltry, claiming the town was worth 40 million pesos, and that "it had cost much blood, so let them come".[12]

On September 9 the invaders landed two separate forces. One large force, numbering about 160, plundered some plantations near the Charleston neck, but was recalled when the Governor Johnson sent militia out in boats to oppose them. A second smaller force was landed on James Island, but was also driven away by the threat of opposition.[18] Late that night Johnson received word that the party on the neck was still active, and sent Lieutenant Colonel Rhett with 100 men to investigate. Arriving around daybreak on the 10th, they apparently surprised the invaders. The invaders fled after a brief skirmish, but about 60 were captured, and as many as 12 invaders were killed along with one of the defenders.[12][19][20] On September 11 Lieutenant Colonel Rhett sailed the colonial flotilla out to find the invaders, only to discover that they had sailed off.[21]

The next day the Brillant showed up, unaware of what had just transpired.[21] Her captain had misjudged the distance from St. Augustine and had made landfall further north before turning around.[12] General Arbousset landed his troops east of Charles Town, but the Brillant was captured by the colonial fleet; Arbousset and his men surrendered after suffering 14–30 killed in a brief battle with the Carolina militia.[12][21] The prisoners included 90 to 100 Indians; most of these were "sold for slaves".[12]

Aftermath

[edit]Carolina officials declared October 17 a day of thanksgiving for their successful defense.[22] The large number of prisoners, however, caused them some trouble. They sent about one third of them off to Virginia, expecting that they would be transported to England. However, by the time the prisoners arrived in Virginia, the annual merchant fleet had already sailed. Virginia authorities were unhappy that they now had to hold the prisoners, who would otherwise have been set free with the ship they arrived on.[23]

In response to the Franco-Spanish expedition, Carolinians led Native American raiding expeditions that besieged Pensacola, one of the few remaining Spanish outposts in Florida.[24] They also mobilized Native American forces to attack Mobile, but these efforts were frustrated by French diplomatic activities in the Native American communities and also by false rumors of another Franco-Spanish expedition.[25]

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b Simms, p. 81

- ^ a b Gallay, p. 151

- ^ TePaske, p. 117

- ^ Crouse, p. 250

- ^ Crouse, p. 251

- ^ Crouse, pp. 251–252

- ^ Crouse, p. 252

- ^ Pothier, Bernard (1979) [1969]. "Le Moyne d'Iberville at d'Ardillières, Pierre". In Hayne, David (ed.). Dictionary of Canadian Biography. Vol. II (1701–1740) (online ed.). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- ^ Higginbotham, p. 238

- ^ a b Higginbotham, p. 284

- ^ Higginbotham, p. 285

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Gallay, p. 152

- ^ Pezuela, p. 24

- ^ a b c Marley, p. 250

- ^ a b c Snowden, p. 145

- ^ Simms, p. 80

- ^ Jones, p. 8

- ^ Jones, p. 9

- ^ Jones, p. 10

- ^ Simms, p. 82

- ^ a b c Snowden, p. 146

- ^ Jones, p. 6

- ^ Jones, p. 5

- ^ Crane, p. 88

- ^ Crane, pp. 89–91

References

[edit]- Crane, Verner W (1956) [1929]. The Southern Frontier, 1670–1732. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. hdl:2027/mdp.39015051125113. ISBN 9780837193366. OCLC 631544711.

- Crouse, Nellis Maynard (2001) [1954]. Lemoyne d'Iberville: Soldier of New France. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 978-0-8071-2700-1. OCLC 237512799.

- Gallay, Allan (2003). The Indian Slave Trade: The Rise of the English Empire in the American South. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-300-08754-3. OCLC 48013653.

- Higginbotham, Jay (1991) [1977]. Old Mobile: Fort Louis de la Louisiane, 1702–1711. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 978-0-8173-0528-4. OCLC 22732070.

- Jones, Kenneth R (January 1982). "A "Full and Particular Account" of the Assault on Charleston in 1706". The South Carolina Historical Magazine. Vol. 83, no. 1. pp. 1–11. JSTOR 27567719.

- Marley, David (2008). Wars of the Americas: A Chronology of Armed Conflict in the Western Hemisphere, Volume 1. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1598841008. OCLC 180907562.

- de la Pezuela, Jacobo (1863). Diccionario Geográfico, Estadístico, Histórico, de la Isla de Cuba, Volume 3 (in Spanish). Madrid: J. Bernat. OCLC 28785605.

- Simms, William Gilmore (1860). The History of South Carolina from its First European Discovery to its Erection into a Republic. New York: Redfield. p. 80. OCLC 491137.

- Snowden, Yates, ed. (1920). History of South Carolina, Volume 1. Chicago and New York: Lewis Publishing. p. 145. OCLC 2395214.

- TePaske, John J (1964). The Governorship of Spanish Florida, 1700–1763. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. OCLC 478311.

- Battles in South Carolina

- Naval battles of the War of the Spanish Succession involving England

- Naval battles of the War of the Spanish Succession involving France

- Naval battles of the War of the Spanish Succession involving Spain

- Pre-statehood history of South Carolina

- Conflicts in 1706

- Queen Anne's War

- 1706 in North America

- Colonial South Carolina