Lee McClung

| |

| Yale Bulldogs | |

|---|---|

| Position | Halfback |

| Class | Graduate |

| Personal information | |

| Born: | March 26, 1870 Knoxville, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Died: | December 19, 1914 (aged 44) London, England |

| Height | 5 ft 10 in (1.78 m) |

| Weight | 165 lb (75 kg) |

| Career history | |

| College |

|

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| College Football Hall of Fame (1963) | |

| 22nd Treasurer of the United States | |

| In office November 1, 1909 – November 21, 1912 | |

| President | William Howard Taft |

| Preceded by | Charles H. Treat |

| Succeeded by | Carmi A. Thompson |

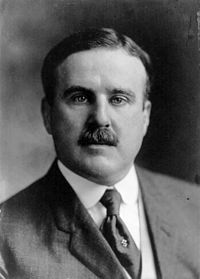

Thomas Lee "Bum" McClung (March 26, 1870 – December 19, 1914) was an American college football player and coach who later served as the 22nd Treasurer of the United States.

Early career

[edit]McClung was born in Knoxville, Tennessee. His father was Frank H. McClung, a merchant, and he was related to Albert Sidney Johnston and John Marshall. McClung graduated from Phillips Exeter Academy.

Yale

[edit]

He continued his education at Yale University, where he was a member of the Yale Bulldogs football team. McClung, who was always known as Lee from his college days onward, was perhaps the best-known football player in the country while playing for the Yale Bulldogs. He is thought to have designed the cutback play. In his athletic prime, he stood 5'10", weighed between 165 and 180 lbs., was on the varsity baseball team, and played in every football season from 1888 to 1891 on teams that compiled a 54–2 record and a 2,269–49 point total.[n 1] McClung by himself was credited with scoring 176 points in 1889 and 494 in his career. He was captain of the unscored-upon Yale football team of 1891 (13–0 record, 488–0 point record), graduating the following year with a Bachelor of Arts degree. He never left a game during injury, despite football being considerably rougher at the time. On November 21, 1891, his famous team of eleven defeated Harvard 10–0, avenging their hard-fought loss of the year before. He played his last college game against Princeton five days later, on Thanksgiving, with the very same eleven Yale players defeating the Tigers 19–0.

He was also a class leader, received the largest number of votes as its most popular member in his senior year, and was a member of the Skull and Bones secret society.[1] He was chairman of his class's Junior Promenade Committee.

McClung returned to New Haven in the fall for many years to assist in coaching. His reputation was long-lasting on the gridiron, and in 1941, even Time magazine was still referring to "a turtlenecked Yale man of the Bum McClung era."[2] He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1963.

Railroad

[edit]McClung spent the year after graduation traveling in Europe and California, where he became the second coach at the University of California. He then entered the service of the St. Paul & Duluth Railroad Company at St. Paul, Minnesota. In 1899 he joined the Southern Railway Company and remained with it until 1901, when he became assistant to the second vice president of the company. McClung became assistant freight traffic manager of the company in 1902, and retained this position until 1904, when he was appointed treasurer of Yale University, assuming that office on December 15, 1904. While in this position, he drew fire for writing satirically about the sale of the defunct Ingham University, having called it "a defunct college that we should be very pleased to sell on very low terms to any one making due application... If it may prove an incentive to the consummation of the deal I should be very much pleased to throw in a cemetery which is located on the grounds."[3] He also modernized treasury and accounting methods at the university.

Treasurer

[edit]On September 23, 1909, President William Howard Taft appointed McClung, a Southern Republican, as Treasurer of the United States. He took office on November 1 of that year. He was paid $8,000 annually. On January 8, 1910, he handed his predecessor a check for $1,260,134,946.88 ⅔, an acknowledgment of the money and securities in the department as of the day McClung took office; it took a little over two months to count all the assets, as is customary when a Treasurer departs. This was said to have been the largest financial transaction from man to man in world history at the time.[4] During his time in office, he urged that worn, dirty banknotes be withdrawn at a higher rate in order to establish a sanitary currency.[5] McClung served until his resignation of November 14, 1912 became effective a week later. He resigned his post because of a dispute in the Treasury Department, a so-called "mutiny" led by A. Piatt Andrew, then Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, who had troubles with Secretary Franklin MacVeagh which involved McClung. Andrew, who resigned on July 3 of that year, criticized MacVeagh's lax business methods and poor administrative skills, naming several Treasury officials as agreeing with him, including McClung. MacVeagh asked McClung to repudiate Andrew's statement concerning him, but he refused, and relations between them became strained. However, President Taft called a truce at the Treasury until after the election that year, with McClung announcing his resignation nine days after Taft's decisive defeat.[6]

After McClung left office, his successor, Carmi A. Thompson, gave him an even bigger check on December 4, 1912, amounting to $1,519,285,908.57 ⅔.[7] The day before, he had made a speech in Pittsburgh claiming that "It is physically possible to steal $100,000,000 from the Treasury of the United States."[8]

McClung was a director of the Phoenix Mutual Life Insurance Company of Hartford, Connecticut, a director of the Marion Institute of Alabama, a national councilman of the Boy Scouts of America, and treasurer of the American Association for Highway Improvement. He was a member of the Metropolitan, Riding, and Chevy Chase Clubs of Washington, the University Club of New York City, and the Graduates and New Haven Lawn Clubs of New Haven. He was also elected president of the Yale Alumni Association of Washington on December 22, 1910. McClung never married. He had two brothers who went to Yale.

Death

[edit]McClung died in a private hospital in London after a three-months' illness of typhoid fever contracted at Frankfurt.[9] His brother C. M. was with him when he died. His body was returned to the United States on board the steamer St. Paul, which left Liverpool on December 26, 1914. His funeral service took place at St. Thomas Episcopal Church, New York on January 4, 1915; he was buried in Knoxville's Old Gray Cemetery two days later following additional services at his sister's home.

One of his obituaries reminisced: "Ah! A remarkable athlete, a wonderful football player, a lovable classmate, a diligent student, a manly man–a type Yale men idealize for emulation. Such was Lee McClung."[10]

Head coaching record

[edit]| Year | Team | Overall | Conference | Standing | Bowl/playoffs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| California Golden Bears (Independent) (1892) | |||||||||

| 1892 | California | 2–1–1 | |||||||

| California: | 2–1–1 | ||||||||

| Total: | 2–1–1 | ||||||||

Notes

[edit]- ^ It was unusual to make the team as a freshman at the time, but McClung did, being the only freshman to play on the noted 1888 team.

References

[edit]- ^ "Present Day History and Geography". The School Journal. 77 (3): 106. November 1909.

- ^ "New Picture", Time, March 3, 1941.

- ^ "Sale of Ingham University", The New York Times, December 18, 1906, p. 8.

- ^ "Receipt for $1,260,134,946.", The New York Times, January 9, 1910, p. 12.

- ^ "Urges Cleaner Currency", The New York Times, October 3, 1910, p. 2.

- ^ Treasury Row Finds Victim in M'Clung, The New York Times, November 15, 1912, p. 6.

- ^ "Vast U.S. Fund Counted", The Washington Post, December 5, 1912, p. 6.

- ^ "Chance to Loot Treasury", The Washington Post, December 4, 1912, p. 1.

- ^ "Lee McClung Is Dead.", The New York Times, December 20, 1914, p. 15.

- ^ "Late Lee M'Clung Football Marvel; Was Also Star for Yale on Diamond", The Washington Post, January 17, 1915, p. S2.

External links

[edit]- 1870 births

- 1914 deaths

- 19th-century American politicians

- 19th-century players of American football

- American football drop kickers

- American football halfbacks

- Treasurers of the United States

- Yale Bulldogs football players

- All-American college football players

- College Football Hall of Fame inductees

- Phillips Exeter Academy alumni

- Players of American football from Knoxville, Tennessee

- Deaths from typhoid fever in the United Kingdom

- Members of Skull and Bones