Lebrija

Lebrija | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 36°55′10″N 6°04′41″W / 36.91944°N 6.07806°W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Autonomous community | Andalusia |

| Province | Seville |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Pepe Barroso (PSOE) |

| Area | |

• Total | 372 km2 (144 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 37 m (121 ft) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

• Total | 27,432 |

| • Density | 74/km2 (190/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Lebrijanos |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 41740 |

| Website | Official website |

Lebrija (Spanish pronunciation: [leˈβɾixa]) is a city and municipality of Spain located in the autonomous community of Andalusia, most specifically in the Province of Sevilla. It straddles the left bank of the Guadalquivir river, and the eastern edge of the marshes known as Las Marismas.[2]

According to a 2008 population census, it has 26,046 inhabitants, and has an area surface of 372 km2, making it one of the biggest municipalities in the province. The nearest municipalities are El Cuervo and Las Cabezas de San Juan, in Seville and Trebujena and the city of Jerez de la Frontera in the province of Cádiz.

The main productive activity is agriculture, with beet, cotton, wheat and various fruits its main products. Winemaking activities are also prominent with Manzanilla and other finos too. Lebrija is also known for its pottery and earthenware heritage, including búcaros. The farmers of this area were the first to cultivate corn brought over from the Americas.

History

[edit]There has been human presence in the area since the Bronze Age, although the founding of Lebrija, possibly did not take place till the Phoenicians arrival, who baptised the settlement as Lepriptza, then to be renamed Nebrissa, during Tartessian times.

Originally, it was a port on the shores of the Lacus Ligustinus, a large inner lake surrounded by the Guadalquivir River and its tributaries and coastal sand bars to the South. The lake later filled with sediment, and gradually gave way to the current Guadalviquir marshy lowlands or, in Spanish, las Marismas.

Lebrija is also the Nabrissa or Nebrissa, surnamed Veneria, of the Romans; by Silius Italicus.[2] According to local historian José Bellido, the word "veneria", (Latin: "that which venerates (worships)") makes reference to the mythical foundation of Lebrija by the god Dionysus (Bacchus): "Where special veneration is given to Bacchus, there where the swift satyres and the menades, at night celebrate the mysteries of that god, with their heads covered up with a deer skin".[3]

Nebrishah was a strong and populous place during the period of Moorish domination (from 711); it was taken by King St Ferdinand in 1249, but again lost, and became finally subject to the Castilian crown only under Alfonso the Wise in 1264.[2]

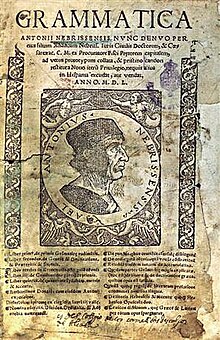

Lebrija was the birthplace of Antonio de Nebrija (1444–1522), also known as Antonius Nebrissensis, one of the most important Renaissance leaders in Spain, author of the first published grammar study of any modern European language, the tutor of Queen Isabella, and a collaborator with Cardinal Jiménez de Cisneros in the preparation of the Complutensian Polyglot Bible.[2]

Lebrija was granted city status by letters patent in 1924.

History of the Jornalero movement

[edit]In 1903, the first general strike was recorded and documented by Spanish writer Azorín. During the Spanish Second Republic, Lebrija was always a Frente Popular stronghold, as it has been an Anarchist one in the previous century. A process of Agrarian reform was started with some collectivisation of farms[4] and expropriation of land from absentee landlords. This was put to an end with the army rebellion, which led to the Spanish Civil War and ultimately to the Francoist victory.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Lebrija, together with Jerez and Morón de la Frontera, became a focus of Jornalero protests (peasants without land) due to their poor living condition and expectations. As a result, a regime of "community work", guaranteeing a minimum salary during a few months every year, was established.[5] Shortly after Francisco Franco's death, on 6 January 1976, around one hundred jornaleros locked themselves up in the parish church to express their political demands, only to be removed by the Civil Guard, but not before they have voiced their consigns using the church tower loudspeakers several times:

"We want the miscultivated fields and lands to be given to jornaleros and small owners. We want subsidies for the unemployed all year round. We want collective agreements for the whole sector and a right to retirement at 60. We want trade union liberty and freedom for all political prisoners and exiles..."[6]

Main sights

[edit]

The area has remnants of its Muslim past among its old buildings. Its chief buildings are a ruined Moorish castle and the parish church, Santa María de la Oliva, one of the finest churches in the province of Seville that combines a variety of styles: Mudéjar, Renaissance and Baroque,[7] dating from the 14th century to the 16th, and containing some early specimens of the carving of Alonso Cano (1601–1667).[2]

The campanile tower was inspired by the Giralda, of the Cathedral of Seville, and it is commonly known as "La Giraldilla" (little Giralda).

The Casa de la Cultura (Cultural Center) was built in the 18th century in Andalusian Baroque style. Originally, it was used as a wheat silo for the Archbishop of Seville and housing for the local Catholic chapter. The Diezmos and tributes paid by the town people to the church were kept here. In 1982, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party in charge of Lebrija City Council at the time bought the property and its restoration began. It was reopened in 1986 as the "Casa de la Cultura", a place dedicated to learning, exhibits, and all sorts of cultural expressions, including dance and music.

The Covent and Church of San Francisco (1585) has always been associated to the Franciscan Order. It is located in the Plaza Manuela Murube (also known popularly as El Pilar), one of the most beautiful and artistic corners of Lebrija. In the same square are located the Old Hospital of Mercy (Hospital de la Misericordia) and Saint Andrew's Asylum (Asilo de San Andrés).

Culture

[edit]The Cruces de Mayo (Holy Crosses of May) is the most well-known and popular festivity in Lebrija. It is held during the first two weekends of May every year. It is a community activity where each neighborhood raises a cross, either using a permanent buttercross site or building them from scratch using flowers, forged iron or wood. These places around the town are then used for dancing and singing, particularly a local form of Sevillanas, known as Sevillanas corraleras.

The local annual fair is dedicated to the patron saint of Lebrija, Our Lady of the Castle, and held around her nameday, on 12 September.

The festivity of the Júas (Andalusian dialect pronunciation of the name Judas) takes place on Saint John's Eve. Local people get together and make lifesize rag dolls, representing celebrities and local politicians. These rag dolls are left outside of houses so they can be admired by others. At midnight they are set alight, together with a fireworks display, thus ending the festivity.

As in Seville and other Andalusian cities, towns, and villages, several hermandades, or religious brotherhoods, march in procession, carrying pasos, lifelike wood or plaster sculptures of individual scenes of the Passion of Jesus Christ or images of the Virgin Mary. Two of the most important hermandades are Los Dolores or El Castillo.

Lebrija is a flamenco centre and the Caracolá, one of the major flamenco festivals in Spain is held there every year in July.

People

[edit]

- Ibrahim bin Ali bin Ahmad (d.1240) - Muslim Moorish scholar who narrated hadeeth (see entry 446 Takmilah of Ibn Abbar)

- Antonio de Nebrija, Andalusian grammarian who wrote the first grammar of the Spanish language, was born in this town.

- Juan Díaz de Solís, navigator and explorer who reached and named the Rio de la Plata Estuary.

- Juan Bernabé (1947–1972), dramatist and theatre director

- Juan Peña "El Lebrijano", flamenco singer.

- Juan Ramón López Caro, former manager of Real Madrid Football Club, of the Spanish La Liga

- David Peña Dorantes, flamenco composer and pianist

- Benito Zambrano, contemporary filmmaker

References

[edit]- ^ Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- ^ a b c d e One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lebrija". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 16 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 351.

- ^ BELLIDO AHUMADA, José (1971): La Patria de Nebrija (noticia histórica). ISBN 84-398-3421-7

- ^ Ley de Arrendamientos Colectivos de 1931

- ^ http://www.ugr.es/~pwlac/G16_08JoseLuis_Solana_Ruiz.html "Las clases sociales en Andalucía. Un recorrido sociohistórico", article by José Luis Solana Ruiz published in Gazeta de Antropología n. 16, 2000. University of Granada, Spain

- ^ "Dosenuna". Archived from the original on 9 May 2006. Retrieved 3 September 2006. "Jornalero y campesino en Andalucía", Revista Militante published by the Movimiento Rural Cristiano

- ^ Lebrija

External links

[edit]- Official website (in Spanish)

- Lebrija in Pueblos de España website (in Spanish)

- Painting and Sculpture in Lebrija, by Juan Cordero Ruiz, Emeritus Professor of University of Seville (in Spanish)