Turkish migrant crisis

The Turkish migrant crisis, sometimes referred to as the Turkish refugee crisis,[1][2][3][4] was a period during the 2010s characterised by a high number of people migrating to Turkey. Turkey received the highest number of registered refugees of any country or territory each year from 2014 to 2019, and had the world's largest refugee population according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).[5][6] The majority were refugees of the Syrian Civil War, numbering 3.6 million as of June 2020[update]. [7] In 2018, the UNHCR reported that Turkey hosted 63.4% of all "registered Syrian refugees."[8]

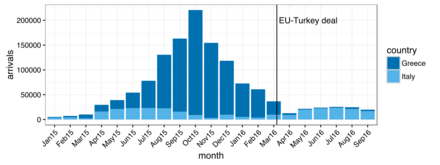

Turkey's migrant crisis is a part of the wider European migrant crisis.[9] On 20 March 2016, a deal between the EU and Turkey to tackle the migrant crisis formally came into effect, which was intended to limit the influx of irregular migrants entering the EU through Turkey.[10] In December 2020, the contract expired and the EU extended it until 2022, giving an extra €485 million to Turkey.[11] The migrant crisis has had a significant impact on Turkey's relationship with the EU.[12]

In response to the crisis, Turkey passed the Law on Foreigners and International Protection and the Temporary Protection,[13] established the Syria–Turkey barrier and the Iran–Turkey barrier to stop smuggling and improve security,[14] and negotiated ceasefires in Syria in order to establish safe zones for civilians.[15]

Major refugee flows

[edit]

Immigration to Turkey has historical roots in the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. Beginning in the late 18th century until the end of the 20th century, an estimated 10 million Ottoman Muslim citizens, the Muhacir and their descendants born after the onset of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire emigrated to Thrace and Anatolia.[16] Turkey became a country of immigration again beginning in the 1980s[17] when crises throughout the Middle East gave rise to wave after wave of refugees seeking safe haven.

The most important factors driving immigration to Turkey are armed conflict, ethnic intolerance, religious fundamentalism, and political tensions.[18] A large influx of refugees came from Iraq from the 1980s.[19]

Influx from the Iran-Iraq War

[edit]The largest group of refugees had been Iranians, until the Syrian civil war. The first influx were Iranians fleeing from the Iranian Revolution in 1980; the Iran–Iraq War began on September 22 of the same year. Both the revolution and the war brought a total of 1.5 million Iranians to Turkey between 1980-1991.[20] These refugees were not recognized as asylum seekers under the terms of the Geneva Convention, because they entered and stayed as tourists; making them Iranian diaspora. The Baháʼí Faith had about 350,000 believers in Iran. According to the UN Special Representative, since 1979, many Baháʼí have left Iran illegally due to state-sanctioned persecution. They often go to Turkey and attempt to continue to the West.[21]

During the same period, 51,542 Iraqis (Iraqis in Turkey) became refugees in Turkey.[22] The Iran–Iraq War and Kurdish rebellion of 1983 caused the first large-scale influx of refugees from the region.

Amnesty International and UNHCR claimed that Turkey was not respecting Iranian refugees' human rights and pressured it to do so.

Influx from the Gulf War

[edit][23] About 450,000 Kurds lived on Iraq-Turkey border when UN SC Resolution 688 was passed, paving the way for the Operation Northern Watch, the successor to Operation Provide Comfort. It was a Combined Task Force charged with enforcing its own no-fly zone above the 36th parallel in Iraq, following refugee flow to Turkey.

During the Gulf War, at least 1 million people fled (almost 30% of the population) to Iran, Turkey, and Pakistan.[24]

Influx from the War in Afghanistan

[edit]Refugee numbers greatly increased in the following years of War in Afghanistan, especially in regards to Afghans and Iraqis. As of January 2010, 25,580 refugees and asylum seekers remain in the country. Of these, 5090 Iranians, 8940 Iraqis, 3850 Afghans, and 2700 "other" (including Somalis, Uzbeks, Palestinians, and others). As of January 2011, 8710 Iranians, 9560 Afghans, 7860 other. As of January 2012 7890 (Iranians, Afghans, and other).[25]

Influx from the Syrian Civil War

[edit]Refugees of the Syrian Civil War in Turkey are Syrian refugees fleeing from the Syrian Civil War. Turkey is hosting over 3.6 million (2019 number) registered refugees and delivering aid reaching $30 billion (total between 2011 and 2018) on refugee assistance.

Influx from the Russo-Ukrainian War

[edit]On 24 February 2022, Russia invaded Ukraine. By 3 March, Turkey announced that 20,000 Ukrainian refugees had entered Turkey since the start of the invasion. Interior Minister Süleyman Soylu said that Turkey was glad to welcome them.[26] By March 8, official figures put the number of Ukrainian refugees in the country at 20,550, of whom 551 were of Crimean Tatar or Meskhetian Turk origin.[27][28] The Ukrainian winner of the 2016 Eurovision Song Contest, Jamala, who is of Crimean Tatar origin, also sought refuge in Turkey.[29] By 23 March, the number of Ukrainian refugees had risen above 58,000.[30][31] The invasion has also led at least 142,488 Russians to relocate to Turkey as of 30 June 2023 reported in The Nordic Monitor[32]

Conditions

[edit]

Turkey did not establish "classic" refugee camps and did not name them as such until 2018. They were managed by the Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency (FEMA type organisation) along its borders. Turkey also established "Temporary Accommodation Centers," such as Öncüpınar Accommodation Facility. Syrians residing outside of TACs live alongside Turkish communities that create short-to-medium term opportunities to harmonize and form economic contributions. The government of Turkey gives them permission to settle in Adana, Afyonkarahisar, Ağrı, Aksaray, Amasya, Bilecik, Burdur, Çankırı, Çorum, Eskişehir, Gaziantep, Hakkâri, Hatay, Isparta, Kahramanmaraş, Karaman, Kastamonu, Kayseri, Kırıkkale, Kırşehir, Konya, Kütahya, Mersin, Nevşehir, Niğde, Sivas, Şırnak, Tokat, Van and Yozgat[33] as well as Istanbul. Refugees from Somalia settled in Konya; Iranis in Kayseri, Konya, Isparta, and Van; refugees from Iraq in Istanbul, Çorum, Amasya, Sivas; and refugees from Afghanistan in Van and Ağrı.

Migrant Presence Monitoring

[edit]Directorate General of Migration Management (DGMM) focuses on the mobility trends, migrant profiles, and urgent needs of migrants. The data generated allows the organisations and the government to plan their short and long-term migration-related program and policies.

Effect on the host country

[edit]Compared to the international refugee regime (see Refugee law), Turkey has a different approach termed as a "morality oriented approach" instead of a security centered approach towards Syrians refugees.[34] Turkey incurs high expenses related to refugee care (housing, employment, education, and health), including medical expenses, with minimal support from other countries.[35]

Refugees cause an increase in food prices and property prices/rent. Low-paid refugees also increase the unemployment rate in southern Turkey.[36]

Prices have increased in critical areas such as food and transportation which has affected both the refugees and various communities with Turkish citizen communities all across Turkey. Many families across Turkey had to reduce their food consumption or had to opt to worse living conditions than they previous had. [37]

Security impact

[edit]As the migrant crisis developed at the most complex geostrategic position in the world, the situation contained ongoing active, proxy, or cooling wars as Turkey shared borders with Iraq (2003 US-led invasion, Iraq War (2003–2011), and Iraqi insurgency (2003–2011)), Iran (Iran–Israel proxy conflict), Syria (Syrian civil war), Georgia (Russo-Georgian War), Azerbaijan (Nagorno-Karabakh conflict), Greece and Bulgaria. In line with the escalating fragility in the region, Turkey directly joined the fight against Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (Turkey–ISIL conflict) in August 2016. The dynamics of the Syrian civil war spilled over into Turkish territory (ISIL rocket attacks on Turkey (2016)). ISIS carried out a series (2013 Reyhanlı bombings, 2015 Suruç bombing, March 2016 Istanbul bombing) of attacks against Turkish civilians by using suicide bombers. The deadliest terrorism in Turkish history, as of 2019, The ISIS attack (2015 Ankara bombings) against a peace rally.

Syria–Turkey and Iran–Turkey barrier

[edit]

The border between the Syrian Arab Republic and the Republic of Turkey is about 822 kilometres (511 mi) long.[38] The Syria–Turkey barrier is a border wall and fence under construction along the Syria–Turkey border aimed at preventing illegal crossings and smuggling.[14]

The Iran–Turkey barrier, finished spring 2019, at the Turkey-Iran border aimed to prevent illegal crossings and smuggling across the border. It will cover 144 kilometres (89 mi) of the very high mountainous 499 kilometres (310 mi) border with natural barriers.

Migrant smuggling

[edit]In the Black Sea region, countries are both sources and destinations for refugees. For the destination of Turkey; originating Moldova, Ukraine, Russian Federation, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan are targets for human trafficking (migration using ships, ship operators are smugglers). The top five countries of destination in the region between 2000 and 2007 were Russia (1,860), Turkey (1,157), Moldova (696), Albania (348), and Serbia (233).[39]

A crackdown by Turkish police has resulted in the termination of a network that mainly helped Afghan, Iraqi and Syrian nationals cross into European countries.[40]

Refugees and spillover

[edit]See: Spillover of the Syrian Civil War#Turkey, Refugees as weapons#Syrian Civil War

In Turkey, public opinion towards intervention is correlated with their daily exposure to refugees. In Turkish people, emphasising the negative forces created by hosting refugees, including their connection with militants, increases support for intervention. Turkish people living at the border do not support intervention. Turkey does not put refugees camps at the border; they are distributed across Turkey.[41]

Response to the refugee crisis

[edit]UN agencies have a Regional Refugee and Resilience Plan co-led by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees and the United Nations Development Programme under Turkey. Private international non-governmental organizations work in partnership with Turkish non governmental organisations (NGOs) and associations to support the delivery of services through national systems, help link refugees and asylum seekers with governmental services.

Law on Foreigners and International Protection and the Temporary Protection

[edit]The Government of Turkey recognized that the traditional immigration laws need to be organised and updated under new circumstances, passing the first domestic law on asylum, which was before covered under secondary legislation such as administrative circulars.[42]

The rules and regulations in providing protection and assistance to Syrians is established by "The Law on Foreigners and International Protection and the Temporary Protection Regulation." It provides the legal basis of their "refugee status" and establishing temporary protection for Syrians and international protection for applicants and refugees of other nationalities. The basis of any/all assistance to refugees, including access to health and education services, as well as access to legal employment is defined under this law.[43] It states that foreigners and others with international protection will not be sent back to places where they will be tortured, suffer inhumane treatment or punishment that is humiliating, or be threatened due to race, religion, or group membership.[44] It also created an agency under the Turkish Ministry of Justice on international protection, which also implements related regulations. Investigative authority is established to question marriages between Turkish citizens and foreigners for the “reasonable suspicions” of fraud.[45] People who are issued uninterrupted residence permits and reside in Turkey for eight years will be able to receive unlimited residence permits.[45]

As of 16 March 2018, there is a modification to law; following the passage of the law 21 official "Temporary Protection Centres" (TPCs) in provinces along the Syrian border established,[46] the Directorate-General of Migration Management of Turkey (DGMM), under the Ministry of Interior, has assumed responsibility for TPCs from Disaster and Emergency Management Presidency.

Migration diplomacy

[edit]

International migration is an important domain at foreign policy development.

In February 2016, Erdoğan threatened to send the millions of refugees in Turkey to EU member states,[48] saying: "We can open the doors to Greece and Bulgaria anytime and we can put the refugees on buses ... So how will you deal with refugees if you don't get a deal?"[49]

Accession to the EU

[edit]Migration is part of accession of Turkey to the European Union. On March 16, 2016, Cyprus had become a hurdle to the EU-Turkey deal on the migrant crisis. The EU linked advancing membership bid to a settlement of the decades-old Cyprus dispute, further complicating efforts to win Ankara's help in resolving Europe's migration crisis.[50]

2015 EU-Turkey Joint Action Plan

[edit]

In 2012, the governments of Turkey and Greece have agreed to work together, to implement border control.[52] In response to Syrian crisis; Greece built a razor-wire fence in 2012 along its short land border with Turkey.[53]

A period beginning in 2015, The European migrant crisis is characterized by rising numbers of people arriving in the European Union (EU) from across the Mediterranean Sea or overland through Southeast Europe. In September 2015, Turkish provincial authorities gave approximately 1,700 migrants three days to leave the border zone.[54] As a result of Greece's diversion of migrants to Bulgaria from Turkey, Bulgaria built its own fence to block migrants crossing from Turkey.[53]

The EU-Turkey Joint Action Plan prioritizes border security and develops mechanisms to keep refugees inside Turkey [prevent migration to EU states].[36] The amount allocated [EU: €3 billion] for financial support for 2016–2018 will ease the financial burden [Turkey: $30 billion between 2011 and 2018] but not better living conditions.[36]

These are the items as stated in the agreement:[36]

- All new irregular migrants crossing from Turkey to the Greek islands as of 20 March 2016 will be returned to Turkey;

- For every Syrian being returned to Turkey from the Greek islands, another Syrian will be resettled to the EU;

- Turkey will take any necessary measures to prevent new sea or land routes for irregular migration opening from Turkey to the EU;

- Once irregular crossings between Turkey and the EU are ending or have been substantially reduced, a Voluntary Humanitarian Admission Scheme will be activated;

- The EU will, in close cooperation with Turkey, further speed up the disbursement of the initially allocated €3 billion under the Facility for Refugees in Turkey. Once these resources are about to be used in full, the EU will mobilize additional funding for the Facility up to an additional €3 billion to the end of 2018;

- The EU and Turkey will work to improve humanitarian conditions inside Syria.

— EU-Turkey Joint Action Plan

European states deny refugees from Turkey. On 18 May 2016, lawmakers from the European Parliament's Subcommittee on Human Rights (DROI) have said that Turkey should not use Syrian refugees as a bribe for the process of visa liberalization for Turkish citizens inside the European Union.[55]

The UNHCR (not a party) criticized and declined to be involved in returns.[56] Médecins Sans Frontières, the International Rescue Committee, the Norwegian Refugee Council and Save the Children declined to be involved. These organization object the blanket expulsion of refugees contravened international law.[57]

"Safe Country" for EU

[edit]In 2019 Greece resumed deportations in response to an increase in refugees over the summer months.[58]

"Safe zone" for refugees

[edit]The Syrian peace process and de-escalation are ongoing efforts beginning as early as 2011. The return of refugees of the Syrian civil war is the returning to the place of origin (Syria) of a Syrian refugee. Turkey promoted the idea of de-escalation regions from 2015, world powers declined to help create a zone (example: Iraq safe zone established by Operation Provide Comfort) to protect civilians.[15] Regarding for the safety of the refugees, progress needs to be made before any significant returns can be planned for. Turkey, Russia and Iran agreed in 2017 to create the Idlib demilitarization (2018–present). (March 2017 and May 2017 Astana talks: De-escalation zones) As of 2019, the Idleb and Eastern Ghouta de-escalation zones remain insecure. President Erdogan stated that Syria's Idlib de-escalation zone was slowly disappearing and that the "safe zone is nothing more than a name".[59] In 2019, the Northern Syria Buffer Zone, a thin strip of the border in northern Syria, will be used as a “safe zone”. This can only be used if Turkey finds a way to bridge the conflicting goals of Russia and the United States. A safe zone will stem the wave of migrations, but Turkey will also need to clear its border of Islamic State and Kurdish militia fighters.[15]

See also

[edit]Further reading

[edit]- Kivilcim, Zeynep (2019). "Migration Crises in Turkey". In Menjívar, Cecilia; Ruiz, Marie; Ness, Immanuel (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Migration Crises. Oxford Handbooks. pp. 426–444. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190856908.013.48. ISBN 978-0-19-085690-8.

- "793 women subjected to rape, sexual harassment in custody in Turkey since 1997: report". Turkish Minute.

References

[edit]Citations

- ^ Bryza, Matthew (16 July 2018). "Turkey and the migration crisis: a positive example for the Transatlantic community". euractiv.com. Auractive. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ Kivilcim, Zeynep (2019). "Migration Crises in Turkey". In Menjívar, Cecilia; Ruiz, Marie; Ness, Immanuel (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Migration Crises. Oxfordh Hndbooks. pp. 426–444. doi:10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190856908.013.48. ISBN 978-0-19-085690-8. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ Staff (30 November 2016). "Turkey's Refugee Crisis: The Politics of Permanence". Crisis Group. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Turkey uses refugee crisis to up the ante". BBC News. 2016-02-08. Archived from the original on 2021-12-09. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- ^ "(Tab1, second column)". Archived from the original on 2018-07-10. Retrieved 2020-03-05.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2021-08-10. Retrieved 2022-02-20.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Situation Syria Regional Refugee Response". United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. Archived from the original on 2018-03-05. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- ^ "Total Persons of Concern by Country of Asylum". data2. UNHCR. Archived from the original on 19 July 2019. Retrieved 24 September 2018.

- ^ "Migrant crisis: EU-Turkey deal comes into effect". BBC News. 2016-03-20. Archived from the original on 2021-12-08. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- ^ "EU-Turkey migrant deal: A Herculean task". BBC News. 2016-03-18. Archived from the original on 2021-12-08. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- ^ "EU finishes contracting $7.3 bln refugee deal with Turkey". hurriyetdailynews. 17 December 2020. Archived from the original on 8 December 2021. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- ^ Beken Saatçioğlu, "The European Union's refugee crisis and rising functionalism in EU-Turkey relations." Turkish Studies 21.2 (2020): 169–187.

- ^ "Turkey: New Law on Foreigners and International Protection". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 2021-12-09. Retrieved 2021-12-08.

- ^ a b The Daily Telegraph: "Turkey to build 500-mile wall on Syria border after Isil Suruc bombing" by Nabih Bulos Archived 2019-07-29 at the Wayback Machine 23 Jul 2015

- ^ a b c Coskun, Orhan (6 September 2016). "With Syria 'safe zone' plan, Turkey faces diplomatic balancing act". Reuters. Reuters. Reuters. Archived from the original on 1 September 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2019.

- ^ Sarah A.S. Isla Rosser-Owen, MA Near and Middle Eastern Studies (thesis). The First 'Circassian Exodus' to the Ottoman Empire (1858–1867), and the Ottoman Response, Based on the Accounts of Contemporary British Observers. Page 16: "... with one estimate showing that the indigenous population of the entire north-western Caucasus was reduced by a massive 94 percent". Text of citation: "The estimates of Russian historian Narochnitskii, in Richmond, ch. 4, p. 5. Stephen Shenfield notes a similar rate of reduction with less than 10 percent of the Circassians (including the Abkhazians) remaining. (Stephen Shenfield, "The Circassians: A Forgotten Genocide?", in The Massacre in History, p. 154.)"

- ^ Boluk, Gulden (2016). "Syrian Refugees in Turkey: between Heaven and Hell?" (PDF). Mediterranean Yearbook (Observatory of Euro Mediterranean Policies) ) (2016): 118. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ Ahmet îçduygu, 1996, Transit Migrants in Turkey, Boğaziçi Journal, Vol. 10, No. 1-2, p. 127

- ^ Ihlamur-Öner, S. G. (2014). “Turkey’s Refugee Regime Stretched to the Limit? The Case of Iraqi And Syrian Refugee Flows”, Perceptions, Autumn 2013, Volume Xviii, Number 3, Pp. 191–228.

- ^ Latif, D. (2002). “Refugee Policy of the Turkish Republic”, The Turkish Year Book, Vol. Xxxiii, Pp. 12.

- ^ UN General Assembly, A/52/472, 15 October 1997, the expulsion of members of Bahá'í Faith

- ^ Kaynak, M. et al. (1992). Iraklı Sığınmacılar ve Türkiye (1988–1991), Ankara: Tanmak. page 25

- ^ Galbraith, P.W (2003). "Refugees from the war in iraq: what happened in 1991 and what may happen in 2003" (PDF). Migration Policy Institute (2). Archived (PDF) from the original on September 8, 2013. Retrieved March 10, 2014.

- ^ Human Rights Watch. GENOCIDE IN IRAQ: The Anfal Campaign Against the Kurds, A Middle East Watch Report. New York City: Human Rights Watch, 1993.

- ^ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Turkey". UNHCR. Archived from the original on 2019-08-10. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ^ Cetinguc, Cem (2022-03-07). "Interior Minister Soylu: Over 20,000 Ukrainian citizens were evacuated to Turkey amid Russia's invasion". P.A. Turkey. Archived from the original on 8 March 2022. Retrieved 2022-03-08.

- ^ "Over 20,000 Ukrainians arrive in Turkey, says top official". Hürriyet Daily News. March 8, 2022. Archived from the original on 15 March 2022.

- ^ "Türkiye'ye ne kadar Ukraynalı geldi? İçişleri Bakanlığı açıkladı". TR Haber. March 7, 2022. Archived from the original on 17 March 2022.

- ^ "Eurovision winner takes refuge in Turkey after forced to flee Ukraine". Hürriyet Daily News. March 3, 2022. Archived from the original on 5 March 2022.

- ^ "İçişleri Bakanı Soylu: 58 bin Ukraynalı savaş sonrası Türkiye'ye geldi". BBC. 22 March 2022. Archived from the original on 24 March 2022. Retrieved 24 March 2022.

- ^ "Some 58,000 Ukrainians take shelter in Turkey, says minister". Istanbul: Hurriyet daily news. 23 March 2022. Archived from the original on 23 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Some 14,000 Russians flee to Turkey after Ukraine war – Turkey News". Archived from the original on 2022-03-23. Retrieved 2022-04-04.

- ^ "UNHCR". Info.unhcr.org.tr. Archived from the original on 2012-03-03. Retrieved 2013-09-06.

- ^ Aras, N. E. G., & Mencutek, Z. S. (2015). The international migration and foreign policy nexus: the case of Syrian refugee crisis and Turkey. Migration Letters, 12(3), 193.

- ^ Kirişci, K. (2014). Syrian refugees and Turkey's challenges: Going beyond hospitality: Brookings Washington, DC.

- ^ a b c d Boluk, Gulden (2016). "Syrian Refugees in Turkey: between Heaven and Hell?" (PDF). Mediterranean Yearbook (Observatory of Euro Mediterranean Policies) ) (2016): 120. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 February 2022. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- ^ “Türkiye.” European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations, 2 Feb. 2024, civil-protection-humanitarian-aid.ec.europa.eu/where/europe/turkiye_en. Accessed 15 Nov. 2024

- ^ Syria – Turkey Boundary Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine, International Boundary Study No. 163, The Geographer, Office of the Geographer, Bureau of Intelligence and Research, US Department of State (7 March 1978).

- ^ Aghazarm, Christine (2008). Migration in the Black Sea Region : an overview (PDF). International Organization for Migration. p. 11. ISBN 978-92-9068-487-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2017-02-28. Retrieved 2019-09-04.

- ^ "Turkey breaks up a smuggling ring that brought thousands of migrants to Europe". news.trust.org. Reuters. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ Getmansky, Anna; Sınmazdemir, Tolga; Zeitzoff, Thomas (1 October 2019). "The allure of distant war drums: Refugees, geography, and foreign policy preferences in Turkey" (PDF). Political Geography. 74: 102036. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2019.102036. ISSN 0962-6298. S2CID 197996617.

- ^ Cavidan Soykan, The New Draft Law on Foreigners and International Protection in Turkey, 2 Oxford monitor of forced migration 38–47 (Nov. 2012).

- ^ Editorial (24 April 2018). "Assistance to Syrian refugees in Turkey" Conference document (PDF). Brussels: Brussels II Conference. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019. Content is copied from this source, which is © European Union, 1995–2018. Reuse is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged. Conference declaration was drafted by the European Union in close co-ordination with the Turkish Government and the United Nations

- ^ Johnson, Constance (18 April 2013). "Turkey: New Law on Foreigners and International Protection | Global Legal Monitor". Library of Congress. Archived from the original on 1 August 2019. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ a b EU Welcomes New Turkish Law on Foreigners, TODAY’S ZAMAN (Apr. 5, 2013)

- ^ Editorial (24 April 2018). "Assistance to Syrian refugees in Turkey" Conference document (PDF). Brussels: Brussels II Conference. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 June 2019. Retrieved 29 July 2019. Content is copied from this source, which is © European Union, 1995–2018. Reuse is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged. Conference declaration was drafted by the European Union in close co-ordination with the Turkish Government and the United Nations

- ^ "Asylum quarterly report – Statistics Explained". ec.europa.eu. Archived from the original on 2019-07-26. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- ^ "Erdogan to EU: 'We're not idiots', threatens to send refugees". EUobserver. 11 February 2016. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016. Retrieved 30 April 2016.

- ^ "Turkey's Erdogan threatened to flood Europe with migrants: Greek website". Reuters. 8 February 2016. Archived from the original on 26 June 2017. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- ^ NORMAN, LAURENCE. "Cyprus is the latest hurdle to EU-Turkey deal on migrant crisis". MarketWatch. THE WALL STREET JOURNAL. Archived from the original on 2019-08-27. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Arrivals to Greece, Italy, and Spain. January–December 2015" (PDF). UNHCR. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-03-28. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- ^ "Turkish, Greek PMs show unity over illegal migrants". Reuters. Archived from the original on 2016-01-17. Retrieved 2012-04-06.

- ^ a b Sarah Almukhtar; Josh Keller; Derek Watkins (16 October 2015). "Closing the Back Door to Europe". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 6 December 2015. Retrieved 28 November 2015.

- ^ "The Latest: Hundreds Seek to Cross Turkey-Greece Border". The New York Times. Associated Press. 16 September 2015. Archived from the original on 19 September 2015. Retrieved 19 September 2015.

- ^ "Syrian refugees should not be used as bribe for visa-free travel, says EP". hurriyet. Archived from the original on 2017-10-19. Retrieved 2019-08-31.

- ^ "UNHCR redefines role in Greece as EU-Turkey deal comes into effect". UNHCR. 22 March 2016. Archived from the original on 9 May 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ "Refugee crisis: key aid agencies refuse any role in 'mass expulsion'". The Guardian. 23 March 2016. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 27 August 2019.

- ^ staff. "The Latest: Greece resuming migrant deportations to Turkey". THE ASSOCIATED PRESS. Archived from the original on 27 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Turkish President Erdogan says Syria's Idlib slowly disappearing". Reuters. 3 September 2019. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 4 September 2019.