Last of the Mobile Hot Shots

| Last of the Mobile Hot Shots | |

|---|---|

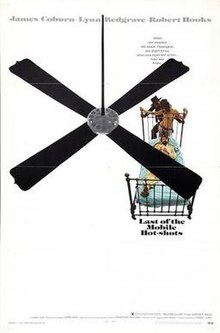

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sidney Lumet |

| Screenplay by | Gore Vidal |

| Based on | The Seven Descents of Myrtle by Tennessee Williams |

| Produced by | Sidney Lumet |

| Starring | James Coburn Lynn Redgrave Robert Hooks |

| Cinematography | James Wong Howe |

| Edited by | Alan Heim |

| Music by | Quincy Jones |

Production company | Sidney Lumet Productions |

| Distributed by | Warner Bros.-Seven Arts |

Release date |

|

Running time | 100 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Last of the Mobile Hot Shots is a 1970 American drama film. The screenplay by Gore Vidal is based on the Tennessee Williams play The Seven Descents of Myrtle, which opened on Broadway in March 1968 and ran for 29 performances.

Sidney Lumet directed Lynn Redgrave as Myrtle, James Coburn as Jeb, and Robert Hooks as Chicken. The film was shot in New Orleans and St. Francisville, Louisiana. It was released by the title Blood Kin in Europe.

Lumet later said "It wasn’t a success. But my feelings are that I would rather do incomplete Tennessee Williams than complete-any-body-else. It was lovely to work on, and I’m sorry I couldn’t solve it.”[1]

Vidal called the film "truly terrible" and "implausible".[2]

Plot

[edit]In New Orleans, Myrtle Kane and Jeb Stuart Thorington, arrive on The Rube Benedict Show where the eponymous host selects them and another couple as contestants. Despite not knowing each other, the couple wins the competition, and decides to earn $3,500 on one condition, to have their marriage ordained by a minister on set. Using the check to restore Waverley Plantation, the couple arrives there, about 100 miles upstream from New Orleans, where Jeb introduces his wife to the decaying plantation mansion his family has owned since 1840. Sometime later, Jeb introduces Myrtle to his multiracial half-brother, Chicken (Robert Hooks) – on his father's side – who'd earned his nickname for hoarding chickens to the rooftop during childhood. Myrtle eventually shares her background in show business, as the last surviving member of an Alabama female quintet, named the Mobile Hot-Shots.

After Myrtle steps out, Jeb and Chicken engage in an argument, where Jeb states his ownership over the mansion, while Chicken states that when Jeb succumbs to terminal lung cancer, he will become the new owner as he is next of kin. Then, Jeb reveals to Myrtle, in a flashback, that he was discharged from the army, he engages in a "war" with Chicken, ordering his half-brother to leave the mansion, though Chicken would return to sign an agreement, making him next subsequent owner.

On her way to dinner, Myrtle grows an immediate dislike for her brother-in-law, though Jeb orders Myrtle to retrieve the agreement from Chicken's wallet in his back pocket. However, she is unsuccessful in her attempts, until Jeb orders his wife to kill Chicken with a hammer, and never to return upstairs without the document. When Myrtle goes downstairs once more, she engages in a conversation until she ultimately reveals, she'd never married Jeb. Chicken refuses to believe it, and orders her to retrieve her marriage license. Myrtle returns upstairs, angering Jeb for not retrieving the agreement, before returning downstairs to present Chicken the marriage license.

After showing the marriage license, Myrtle engages in an extramarital affair, with Chicken. Meanwhile, Jeb, who experiences several flashbacks of his mother, and multiple threesome affairs with several prostitutes, becomes angered that his wife has not returned with the document, and marches downstairs armed with a pistol, where he ultimately burns the agreement. After burning the agreement, Chicken reveals that he is actually the plantation's heir, through his mother rather than the "mistake" produced from an interracial extramarital affair committed by Jeb's father, who later died in World War II. Learning of the revelation, Jeb collapses to the floor, and dies.

Finally, the levee breaks, forcing Chicken and Myrtle to ascend to the rooftop, to escape the surrounding floodwaters, for refuge and sexual fulfillment.

Cast

[edit]- James Coburn as Jeb Stuart Thorington

- Lynn Redgrave as Myrtle Kane

- Robert Hooks as Chicken

- Perry Hayes as George

- Reggie King as Rube Benedict

Production

[edit]In March 1969 Kenneth Hyman announced Warner Bros-Seven Arts would make the film starting March 31 in Louisiana, following two weeks of rehearsal in New York. The title was then Blood Kin.[3]

A number of changes were made from the original play including making James Coburn's character straight and impotent rather than a gay transvestite. James Coburn said during filming that Vidal "has kept all the good things in Tennessee's play and improved on all the bad things." He added, "Sidney is the only director I've ever worked with who makes me feel like I'm working towards a totality instead of a piece of nothing... It's the only role I've ever played of any importance"[4]

The producers gave a dummy script to locals in Louisiana so they would be unaware of the interracial content. This was a precaution taken after the difficulties encountered when a Hollywood unit filmed Hurry Sundown in the state, including locals firing guns at Hooks and Hooks being refused service at a restaurant. Redgrave recalled the Louisiana mansion as "an extraordinary place. A strage, romantic place with a weird sort of atmosphere. That house helped a lot."[5]

Lumet said during filming "I think it'll be a great picture. Maybe it'll work. Maybe it won't."[4]

Coburn said “I thought it would be a wonderful film. After all, James Wong Howe shot it. Gore Vidal wrote the script, Sidney Lumet was the director and we had a good budget. But, somewhere along the way the focus got lost. It didn’t work as a film. When Sidney makes his mind up about something, he’ll go with it, good or bad, right or wrong, he’ll go with it. Unfortunately, he was wrong on that film."[6]

Gore Vidal wrote, "I was in demand after Suddenly Last Summer to adapt practically anything that Tennessee wrote; I made the mistake of taking on what became... The Last of the Mobile Hot-Shots, not the Glorious Bird at his feathery best."[7]

Reception

[edit]Vincent Canby, writing for The New York Times, reviewed the film as a "slapstick tragicomedy that looks and sounds and plays very much like cruel parody—of Tennessee Williams", and he further remarked that the film "is haunted by ghosts of earlier, more memorable Williams characters who are easily identifiable even though there have been some changes in sex and color."[8]

The Los Angeles Times said it "can only be recommended as outrageous camp."[9]

Variety called it a "comic opera travesty" starring "all stumbling puppets manipulated by a catcher’s-mitted Lumet" and "will find whatever audience it has in those who are not yet sated on still another story of Dixie degradation."[10]

Filmink called it "spectacularly miscast" and argued the film help bring an end to Tennessee Williams' popularity with Hollywood studios.[11]

In 1982 Lumet said I have never seen this film a second time and would be afraid to hate it, but, on the other hand, there is a certain humor, a richness, and there are such interesting characters, that maybe I wouldn’t dislike it that much! That play was a bit more extravagant than the others, without the usual lyricism."[12]

Gore Vidal said in 1976 it was "a real lousy film. Sidney Lumet somehow contrived something peculiar with the sound, you could not understand anything that was being said - which could have been a blessing, but it was mysterious in effect."[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Rapf p 63

- ^ Parini, Jay (2015). Empire of self : a life of Gore Vidal. p. 193.

- ^ "James Coburn to star". Calgary Herald. 8 March 1969. p. 8.

- ^ a b Reed, Rex (8 June 1969). "Oh! Baton Rogue - You Just Don't Know What's Going On Out There in the Swamp". Democrat and Chronicle. p. G1.

- ^ "Sin in the deep South". Evening Standard. 11 July 1969. p. 12.

- ^ Goldman, Lowell (Spring 1991). "James Coburn Seven and Seven Is". Psychotronic Video. No. 9. p. 23.

- ^ Vidal, Gore (2009). Snapshots in history's glare. p. 160.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (January 15, 1970). "The Screen: 'Last of the Mobile Hot-Shots' Opens". The New York Times. Retrieved March 29, 2015.

- ^ Thomas, Kevin (4 February 1970). "'Hot shots' in citywide run". The Los Angeles Times. p. 10 Part 4.

- ^ "The Last of the Mobile Hot Shots". Variety Reviews 1968-1970. 31 December 1969.

- ^ Vagg, Stephen (19 November 2024). "What makes a financially successful Tennessee Williams film?". Filmink. Retrieved 19 November 2024.

- ^ Rapf p 98

- ^ Kilday, Gregg (18 April 1976). "Once over lightly from Gore Vidal". The Los Angeles Times. p. 27.

Notes

[edit]- Rapf, Joanna E. (2006). Sidney Lumet: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi.

External links

[edit]- 1970 films

- 1970 comedy-drama films

- American comedy-drama films

- American films based on plays

- 1970s English-language films

- Films directed by Sidney Lumet

- Films scored by Quincy Jones

- Films set in Louisiana

- Films shot in Louisiana

- Films shot in New Orleans

- Films with screenplays by Gore Vidal

- Warner Bros. films

- 1970s American films

- English-language comedy-drama films