La conversione e morte di San Guglielmo

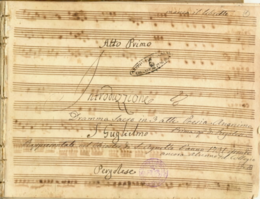

| La conversione e morte di San Guglielmo | |

|---|---|

| Dramma sacro by G. B. Pergolesi | |

First page of the complete manuscript score kept at the Conservatorio San Pietro a Majella | |

| Translation | The Conversion and Death of Saint William |

| Librettist | Ignazio Mancini |

| Language | Italian |

| Premiere | |

La conversione e morte di San Guglielmo (The Conversion and Death of Saint William) is a sacred musical drama (dramma sacro) in three parts by the Italian composer Giovanni Battista Pergolesi. The libretto, by Ignazio Mancini, is based on the life of Saint William of Aquitaine as recounted by Laurentius Surius.[1] It was Pergolesi's first stage work—albeit not properly an opera— possibly written as a study exercise for his conservatory. The work was premiered at the Monastery of Sant'Agnello Maggiore, Naples in the summer of 1731.[2]

Background

[edit]In 1731 Pergolesi's long years of study at the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo in Naples were drawing to a close. He had already begun to make a name for himself and was able to pay off his expenses by working as a performer in religious institutions and noble salons, first as a singer then as a violinist. In 1729–1730 he had been "capoparanza" (first violin) in a group of instrumentalists and, according to a later witness, it was the Oratorian Fathers who made most regular use of his artistic services as well as those of other "mastricelli" ("little maestros") from the Conservatorio.[3] The first important commission Pergolesi received on leaving the school was linked to this religious order and on 19 March 1731 his oratorio La fenice sul rogo, o vero La morte di San Giuseppe (The Phoenix on the Pyre, or The Death of Saint Joseph) was performed in the atrium of their church, today known as the Chiesa dei Girolamini, the home of the Congregazione di San Giuseppe.[4] "The following summer Pergolesi was asked to set to music, as the final exercise of his studies, a dramma sacro in three acts by Ignazio Mancini, Li prodigi della divina grazia nella conversione e morte di san Guglielmo duca d’Aquitania ["The Miracles of Divine Grace in the Conversion and Death of Saint William, Duke of Aquitaine"]. The performance took place in the cloisters of the monastery of Sant'Agnello Maggiore, the home of the Canons Regular of the Most Holy Saviour."[5] The libretto was supplied by a lawyer, Ignazio Maria Mancini, "who indulged in poetical sins as a member of the Arcadian Academy under the name Echione Cinerario. [...] The audience was made up of habitués of the Congregation of the Oratorians, in other words 'the cream of Naples' ...and its success was such that the Prince Colonna di Stigliano, equerry to the Viceroy of Naples, and Duke Carafa di Maddaloni – both of them present – promised the 'little maestro' their protection and opened the doors of the Teatro San Bartolomeo to him, then one of the most popular and important theatres in Naples," where Pergolesi was soon commissioned to write his first opera seria, La Salustia.[6]

The autograph score of San Guglielmo has not survived but the various manuscripts which have been rediscovered show that the drama enjoyed widespread popularity for several years, and not only in Naples: in 1742 it was even revived in Rome, although only as an oratorio with the comic elements of the original removed. The libretto of this version was published.

The work was brought to public attention again in 1942, during World War II: it was staged at the Teatro dei Rozzi, Siena, on 19 September, in a reworking by Corrado Pavolini and Riccardo Nielsen,[7] and was later mounted, apparently in a different stage production, on 18 October at the Teatro San Carlo in Naples.[8] The work was revived again in 1986 in a critical edition by Gabriele Catalucci and Fabro Maestri based on the oldest of the manuscripts, the one to be found at the Conservatorio San Pietro a Majella in Naples, the only manuscript which also contained the comic element represented by Captain Cuòsemo. The music was also performed at the Teatro Sociale of Amelia, conducted by Fabio Maestri himself, and a live recording was made. Three years later, in the summer of 1989, it was revived in another concert performance at the Festival della Valle d'Itria in Martina Franca, with Marcello Panni as conductor.[9] In 2016, at the Festival Pergolesi Spontini in Jesi, Pergolesi's opera saw its latest major staging, in the critical revision by Livio Aragona, conducted by Christophe Rousset and directed by Francesco Nappa.

Artistic and musical characteristics

[edit]Genre

[edit]Dramma sacro ("sacred drama") was a relatively common musical genre in early 18th-century Naples. Its history "developed alongside that of the opera comica and, to a certain extent, the dramma in musica".[10] It differed from contemporary oratorio as established by Alessandro Scarlatti,[9] by the essential element of stage action: it was a genuinely dramatic composition, in three acts, portraying edifying episodes from the Holy Scriptures or the lives of the saints, containing a comic element represented by characters from the common people who often expressed themselves in Neapolitan dialect. This led to problems of mutual comprehension when talking with more elevated characters (such as a saint or an angel) and matters of Christian doctrine and ethics had to be carefully explained to them in minute detail.[11] If the inspiration for this type of drama could partly be found in the autos sacramentales[12] and the comedias de santos[13] introduced to Naples during the era of Spanish domination (1559–1713) it was also in some ways a continuation of the old popular tradition of the sacra rappresantazione (a sort of "mystery play"), meaning "traditional religiosity, saturated in popular hagiography and rather naive in taste", which already featured comic characters expressing themselves in dialect, continual disguises and the inevitable conversion of the protagonists.[9] Drammi sacri were not intended for the theatres but for places connected with houses of worship such as cloisters or parvises, or even for the courtyards of noblemen's palaces, and they were generally produced by the conservatories: students were called on to take part either in their composition or performance. In this way they "learnt the techniques of modern stage production".[14] This pedagogical tradition, which went back to at least 1656, had reached one of its high points at the beginning of the 18th century with the drama Li prodigi della Divina Misericordia verso li devoti del glorioso Sant'Antonio da Padova by Francesco Durante,[11] who later became a teacher at the Conservatorio dei Poveri di Gesù Cristo and one of the greatest of Pergolesi's tutors.

Libretto and structure

[edit]

In 1731 Pergolesi was given the task of setting a complete dramma sacro to music as the final composition of his studies at the Conservatorio. The young Leonardo Leo and Francesco Feo had faced similar tests at the Conservatorio della Pietà dei Turchini almost twenty years earlier. The libretto, supplied by the lawyer Mancini (although described as "anonymous" in the oldest surviving manuscript),[15] concerned the legendary figure of Saint William of Aquitaine, and was set at the time of the religious struggles between Pope Innocent II and the Antipope Anacletus II. In fact, as Lucia Fava explains in her review of the production in Jesi in 2016:

If the plot takes its starting point from an historical event, the internal conflict in the Church between Anacletus and Innocent, the character of San Guglielmo is based on the biographies of three different "Williams": William X Duke of Aquitaine and Count of Poitiers, who really was associated with the historical Saint Bernard of Clairvaux; William of Gellone, another Duke of Aquitaine, who after a life dedicated to warfare and fighting against the Saracens retired to become a monk; and William of Maleval, who crowned his life devoted to heresy and lust with a pilgrimage to Jerusalem and retreat to a hermitage. The conflation of these three figures is the result of a hagiographical tradition which was already well established by the time the libretto was written[16] and was not Mancini's invention.

There are seven characters in the drama, five of them – those of a more elevated social rank and with more spiritual characteristics – are entrusted to higher voices (sopranos). The sources are unclear whether this means castrati or female singers. The remaining two roles, that of the plebeian captain Cuòsemo – a soldier in the entourage of the Duke of Aquitaine who follows his master's path to salvation, although reluctantly – and that of the Devil, are entrusted to bass voices. The character of Alberto, who probably corresponds to the historical figure of William of Maleval's favourite disciple, only has a few bars of recitative in the third act (in fact this character does not even appear in the cast list of the staging in Jesi in 2016). The characters of Saint Bernard and Father Arsenio appear at different moments in the drama (in the first and second act respectively) and were probably intended to be sung by the same performer, making his contribution equal in importance to the other roles: each character has three arias, reduced to two for the title character and increased to four for the more virtuosic role of the angel. In the score in the Biblioteca Giovanni Canna in Casale Monferrato, which follows the libretto of the oratorio version published in Rome in 1742 to the letter, there is also a third aria for Guglielmo, which would "restore the balance" in favour of the theoretically most important character but, according to Catalucci and Maestri, it is difficult to fit this piece into the dramatic action of the Naples manuscript.[17]

The whole opera, not counting the additional aria for Guglielmo, is made up of the following parts:

- a sinfonia before the opera,

- 15 arias,

- four duets,[12]

- a quartet,

- secco recitatives

- two accompanied recitatives[12]

Music

[edit]As far as the musical dimension is concerned, Lucia Fava comments:

[...]The comic dimension is not limited to the presence of Cuòsemo, for typical opera-buffa situations are also recalled by the continual disguises, following on from one another and involving in turn the captain, the angel and above all the devil, as well as by the stylistic features of some arias of the latter or Saint Bernard.

Of course, the musical model adopted by the novice composer is twofold and consists in drastically differentiating the arias for serious characters from those for the comic ones: the former are virtuoso and da capo arias, sometimes full of pathos, sometimes bursting with pride, sometimes sententious, sometimes dramatic, most of them in a 'parlando' style, so as to create some dynamism in the development of the plot; the latter are syllabic, rich in repetitions, monosyllables and onomatopoeic words.

Some of the music also appears in the score of L'Olimpiade, the opera seria Pergolesi composed for Rome just over three years later. The three pieces concerned are:

- The sinfonia[18]

- The Angel's solo "Fremi pur quanto vuoi" in the second act, which corresponds to Aristea's aria "Tu di saper procura" in the first act of L'Olimpiade[19]

- The duet "Di pace e di contento" between San Guglielmo and Father Arsenio, at the end of the second act, which corresponds to the only duet in L'Olimpiade, placed at the end of the first act, "Ne' giorni tuoi felici", between Megacle and Aristea.[20]

Purely on the basis of the chronological facts, non-specialist sources have often spoken of self-borrowings on Pergolesi's part, from San Guglielmo to L'Olimpiade. However, given the original autograph manuscript of the earlier work has not survived, it is quite possible that it was a case of the reuse of music from L'Olimpiade in later Neapolitan revivals of the dramma sacro.[21] Catalucci and Maestri, writing in the 1980s, seemed to favour this second hypothesis when they affirmed that "the texts of the duets are different, but the disposition of the accents in the opera seems to match the musical line more naturally".[22] Nevertheless, Lucia Fava, writing thirty years later, insists that, contrary to "what was once hypothesised, given the non-autograph nature of the only manuscript source" the hypothesis of self-borrowing might be closer to the truth. Whatever the case, the duet, in the version drawn from L'Olimpiade, was "highly celebrated throughout the 18th century"[23] and Jean-Jacques Rousseau made it the archetypal example of the form in the article "Duo" in his Dictionnaire de musique (1767).[24]

Roles

[edit]| Role | Voice type |

|---|---|

| San Guglielmo (Saint William) | soprano |

| San Bernardo (Saint Bernard) | soprano |

| Cuòsemo | bass |

| L'angelo (The Angel) | soprano |

| Il demonio (The Demon) | bass |

| Padre Arsenio (Father Arsenio) | soprano |

| Alberto | soprano |

Synopsis

[edit]Act 1

[edit]William has banished the Bishop of Poitiers for refusing to abandon the legitimate pope. Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, the most famous preacher of the era, arrives at William's court to try to bring him back into the fold of the true Church. Around these two a devil and an angel manoeuvre (along with Captain Cuòsemo). The devil first appears disguised as a messenger and then as a counsellor (under the name Ridolfo). The angel is disguised as a page (named Albinio). Each tries to influence the duke's decisions according to their own secret plans.

Despite Saint Bernard's exhortations, the duke seems to remain inflexible (William's aria, "Ch'io muti consiglio", and Bernard's, "Dio s'offende") and sends Captain Cuòsemo and Ridolfo (the demon) to enforce the banishment of the rebellious bishops. However, the pair are stopped by the angel who attacks his opponent with harsh words (aria, "Abbassa l'orgoglio") to the consternation of Cuòsemo. The captain can only comically boast of his bravery to the devil's face (aria, "Si vedisse ccà dinto a 'sto core"), while the latter proclaims himself satisfied with the way his plans are going (aria, "A fondar le mie grandezze").

William, who seems to have embraced the cause of the war against the pope outright, asks Albinio (the angel) to cheer him up with a song: the angel seizes the opportunity to remind him of his duty as a Christian and sings an aria consisting of an exhortation to a lamb to return to the fold ("Dove mai raminga vai"). William grasps the symbolism but he proclaims that, like the lamb, he "loves freedom more than life itself".

When Bernard returns to the attack with his preaching, however, (accompanied recitative and aria, "Così dunque si teme?... Come non pensi") William's resolution wavers and his mind is opened to repentance. The act ends with a quartet during which the duke's conversion takes place, to the satisfaction of Saint Bernard and the angel and the horror of the demon ("Cieco che non vid'io").

Act 2

[edit]The action takes place in a lonely mountain landscape where William wanders in search of the advice of the hermit Arsenio. Instead he finds the demon, who has adopted the appearance of the hermit. The demon tries to make William reconsider his conversion by appealing to his pride as a warrior (aria, "Se mai viene in campo armato"). The timely intervention of the angel, now disguised as a shepherd boy, unmasks the demon and the angel shows William the way to reach the hermit (aria, "Fremi pur quanto vuoi").

Captain Cuòsemo, who has followed his master on his path to repentance and on his pilgrimage, begs the fake hermit for a morsel of bread but receives only contempt and refusal (duet, "Chi fa bene?"). A second intervention by the angel unmasks the demon again and chases him off, leaving Cuòsemo to curse him (aria, "Se n'era venuto lo tristo forfante"), before continuing his quest again.

William finally meets the real Father Arsenio, who describes the advantages of the hermit's way of life and invites him to abandon the world (aria, "Tra fronda e fronda"). The act concludes with an impassioned duet between the two men ("Di pace e di contento").

Act 3

[edit]William, having obtained the Pope's pardon, is preparing to retreat to a monastery in a remote part of Italy, when the call of the past leads him to join in a nearby battle. Meanwhile, Cuòsemo, who has become a monk at the monastery William has founded, complains about the privations of monastic life and is once more tempted by the devil, this time in the guise of a pure spirit who offers him a stark choice between a return to a soldier's life and the death by starvation which surely awaits him in his new situation (duet, "So' impazzuto, che m'è dato?").

William has been blinded in the battle and, overwhelmed by a sense of sin, finds himself plunged into despair once more (accompanied recitative and aria, "È dover che le luci… Manca la guida al piè"),[25] but the angel intervenes and restores his sight so he can "gather...companions and imitators". Then the demon returns disguised as the ghost of William's late father, urging him to retake the throne of Aquitaine and fulfill his duties to his subjects. This time William is inflexible, arousing the fury of the evil spirit who orders his brother devils to whip William (aria, "A sfogar lo sdegno mio"), but the angel again intervenes and drives off the infernal spirits.

A nobleman from the court of Aquitaine, Alberto, arrives in search of news of William and is intercepted by the devil, who has once more adopted the guise of the counsellor Ridolfo, as in the first act, and who hopes to obtain Alberto's assistance in persuading the duke to return to his former life. Cuòsemo opens the monastery gates then squabbles with the devil over the latter's malicious remarks about monasticism, but eventually he leads the two men to William whom they find ecstatically flagellating himself before the altar surrounded by angels (the angel's aria, "Lascia d'offendere"). The devil is horrified, but Alberto reveals his desire to join the monastery himself, while Cuòsemo offers a colourful description of the hunger and hardships which characterise monastic life (aria, "Veat'isso! siente di'")..

Worn out by his privations, William is nearing death in the arms of Alberto. He resists the last temptation of the devil, who tries to make him doubt the ultimate forgiveness of his sins. But the duke's faith is unshakeable now that Rome has absolved him and he has dedicated himself to a life of repentance. The angel greets William's soul as it flies up to heaven while the devil plunges back to hell vowing to return with renewed fury to continue his campaign of damnation (duet, "Vola al ciel, anima bella").

Recordings

[edit]| Year | Cast (in the order): L'Angelo, San Bernardo/Padre Arsenio, San Guglielmo, Alberto, Cuòsemo, il Demonio) |

Conductor, Orchestra, Notes |

Label |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1989 | Kate Gamberucci, Susanna Caldini, Bernadette Lucarini, Cristina Girolami, Giorgio Gatti, Peter Herron | Fabio Maestri, Orchestra da camera della Provincia di Terni (live recording, 1986) |

CD Bongiovanni Catalogue number: GB 2060/61-2 |

| 2020 | Caterina Di Tonno, Carla Nahadi Babelegoto/Federica Carnevale, Monica Piccinini, Arianna Manganello, Mario Sollazzo, Mauro Borgioni | Mario Sollazzo, Ensemble Alraune (recording on period instruments) |

CD NovAntiqua Records Catalogue number: NA39 |

References

[edit]- ^ De probatis sanctorum historiis, partim ex tomis Aloysii Lipomani, doctissimi episcopi, partim etiam ex egregiis manuscriptis codicibus, quarum permultae antehac nunquam in lucem prodiēre, nunc recens optima fide collectis per f. Laurentium Surium Carthusianum, Cologne, Geruinum Calenium & haeredes Quentelios, 1570, I, pp. 925–948 (accessible online at Google Books).

- ^ Paymer, pp. 764–765

- ^ Hucke and Monson

- ^ The term "Girolamini" (Hieronymites) here does not refer to the monastic order of the same name but to the Oratorian Fathers (more precisely, Congregation of the Oratory of Saint Philip Neri): it derives from the fact that the first "oratory" was created by Saint Philip Neri at the Church of San Girolamo della Carità in Rome (Italian Ministero dei beni cultutali Archived 2016-10-24 at the Wayback Machine).

- ^ Toscani

- ^ Caffarelli, s.n. (first page of the introduction).

- ^ 1942 printed libretto; "Emporium: rivista mensile illustrata d'arte, letteratura, science e varieta"; Volume 96, Edition 574, 1942, p. 454

- ^ Felice De Filippis (ed), Cento anni di vita del Teatro di San Carlo, 1848–1948, Naples, Teatro San Carlo, 1948, p. 213; Casaglia, Gherardo (2005). "Guglielmo d´Aquitania, 18 October 1942". L'Almanacco di Gherardo Casaglia (in Italian).

- ^ a b c Foletto

- ^ Aquilina, p. 89.

- ^ a b Gianturco, p. 118

- ^ a b c Fava

- ^ Gustavo Rodolfo Ceriello, Comedias de Santos a Napoli, nel '600 (with previously unpublished documents); "Bulletin Hispanique", Volume 22, n° 2, 1920, pp. 77–100 (accessible online at Persée).

- ^ Aquilina, p. 89

- ^ Which, according to Catalucci and Maestri, might render the traditional attribution to Mancini unsound (p. 9).

- ^ On this subject see the remarks in the authoritative History of the Religious and Military Monastic Orders by Pierre Helyot and Maximilien Bullot, namely that there was practically no "Duke of Aquitaine, beginning with William 'Towhead'" who had not been confused with Saint William of Maleval (even though, to be perfectly accurate, William "Towhead" was the nickname of the third not the second Duke of Aquitaine). The work of the two French authors only appeared in Italian translation a few years after the premiere of Pergolesi's dramma sacro: Storia degli ordini monastici, religiosi e militari e delle congregazioni secolari (...), Lucca, Salani, 1738, VI, p. 150 (accessible online at Google Books).

- ^ Catalucci and Maestri, p. 10.

- ^ Dorsi, p. 129

- ^ Celletti, I, p. 117.

- ^ Catalucci and Maestri, p. 9.

- ^ Hucke, Pergolesi: Probleme eines Werkverzeichnisses.

- ^ *Catalucci and Maestri, p. 9. In addition, the two authors earlier comment about the sinfonia: "The chronological problem is an open question still unsolved, namely whether the Guglielmo symphony was reused for the opera or vice versa" (p. 10).

- ^ Mellace

- ^ Paris, Duchesne, 1768, p. 182 (accessible online at Internet Archive).

- ^ According to another reading of the libretto it is possible that it was William who blinded himself as a form of self-imposed penance. This was the interpretation adopted by a student production of La conversione staged on 14 July 2011 at Carpi, in the cloisters of the Convent of San Rocco, conducted by their teacher Mario Sollazzo, directed by Paolo V. Montanari, with the Vocal Instrumental Ensemble of the Istituto Superiore di Studi Musicali "O. Vecchi – A. Tonelli", a music school located at Modena and Carpi (cf. Comune di Modena Website Archived 2016-12-20 at the Wayback Machine).

Sources

[edit]- Librettos:

- contemporary printed edition: La conversione di San Guglielmo duca d’Aquitania, Rome, Zempel, 1742 (critical transcription at Varianti all'opera – Universities of Milan, Padua and Siena)

- text taken from the manuscript score to be found at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France in Paris (San Guglielmo d’Aquitania), accessible (only the second part) at Varianti all'opera – Universities of Milan, Padua and Siena

- text taken from the manuscript score to be found at the British Library in London (La converzione di San Guglielmo), accessible at Varianti all'opera – Universities of Milan, Padua and Siena

- text taken from the manuscript score to be found at the Biblioteca Giovanni Canna in Casale Monferrato (La conversione di San Guglielmo duca d’Aquitania), accessible at Varianti all'opera – Universities of Milan, Padua and Siena

- 1942 printed edition: Guglielmo d'Aquitania. Dramma sacro in tre atti di Ignazio Maria Mancini. Revisione e adattamento di Corrado Pavolini. Musica di G. B. Pergolesi. Elaborazionre di Riccardo Nielsen. Da rappresentarsi in Siena al R. Teatro dei Rozzi durante la "Settimana Musicale" il 19 Settembre 1942–XX, Siena, Accademia Chigiana, 1942

- Manuscript score to be found at the library of the Conservatorio San Pietro a Majella in Naples, digitized at OPAC SBN – Servizio Bibliotercario Italiano

- Modern printed edition of the score: Guglielmo d'Aquitania//Dramma sacro in tre parti (1731), in Francesco Caffarelli (ed), Opera Omnia di Giovanni Battista Pergolesi ..., Rome, Amici Musica da Camera, 1939, volumes 3–4 (accessible online as a free Google e-book)

- Frederick Aquilina, Benigno Zerafa (1726–1804) and the Neapolitan Galant Style, Woodbridge, Boydell, 2016, ISBN 978-1-78327-086-6

- Gabriele Catalucci and Fabio Maestri, notes accompanying the audio recording of San Guglielmo Duca d'Aquitania, issued by Bongiovanni, Bologna, 1989, GB 2060/61-2

- (in Italian) Rodolfo Celletti, Storia dell'opera italiana, Milan, Garzanti, 2000, ISBN 9788847900240.

- (in Italian) Domenico Ciccone, Jesi – XVI Festival Pergolesi Spontini: Li Prodigi della Divina Grazia nella conversione e morte di San Guglielmo Duca d'Aquitania; OperaClick quotidiano di informazione operistica e musicale, 9 September 2016

- (in Italian) Fabrizio Dorsi and Giuseppe Rausa, Storia dell'opera italiana, Turin, Paravia Bruno Mondadori, 2000, ISBN 978-88-424-9408-9

- (in Italian) Lucia Fava, Un raro Pergolesi; «gdm il giornale della musica», 12 September 2016

- (in Italian) Angelo Foletto, Quanta emozione nel dramma sacro...; La Repubblica, 5 August 1989 (accessible for free online at the newspaper's archive)

- Carolyn Gianturco, Naples: a City of Entertainment, in George J Buelow, The Late Baroque Era. From the 1680s to 1740, London, Macmillan, 1993, pp. 94 ff., ISBN 978-1-349-11303-3

- (in German) Helmut Hucke, Pergolesi: Probleme eines Werkverzeichnisses; «Acta musicologica», 52 (1980), n. 2, pp. 195–225: 208.

- Helmut Hucke and Dale E. Monson, Pergolesi, Giovanni Battista, in Stanley Sadie, op.cit., III, pp. 951–956

- (in Italian) Raffaele Mellace, Olimpiade, L', in Piero Gelli e Filippo Poletti (editors), Dizionario dell'opera 2008, Milan, Baldini Castoldi Dalai, 2007, pp. 924–926, ISBN 978-88-6073-184-5 (reproduced in Opera Manager)

- Stanley Sadie (editor), The New Grove Dictionary of Opera, New York, Grove (Oxford University Press), 1997, ISBN 978-0-19-522186-2

- Marvin E. Paymer, article on Pergolesi in The Viking Opera Guide (ed. Amanda Holden, Viking, 1993)

- (in Italian) Claudio Toscani, Pergolesi, Giovanni Battista, in Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Volume 82, 2015 (accessible online at Treccani.it)

- This article contains material translated from the equivalent article in the Italian Wikipedia.