La Lutte (newspaper)

La Lutte ('The Struggle') was a left-wing paper published (in French to get around print restrictions on Vietnamese) in Saigon, French-colonial Cochinchina (southern Vietnam), in the 1930s.[1] It was launched ahead of the April–May 1933 Saigon municipal council election as a joint organ of the Indochinese Communist Party (PCI) and a grouping of Trotskyists (which became known as Nhom Tranh Dau, the 'Struggle Group', after La Lutte) and others who agreed to run a joint "Workers' slate" of candidates for the polls.[2][3][4] This kind of cooperation between Trotskyists and Comintern-linked communists was a phenomenon unique to Vietnam.[5] The editorial line of La Lutte avoided criticism of the USSR while supporting the demands of workers and peasants without regard to faction.[6] The supporters of La Lutte were known as lutteurs.[7]

1933 election

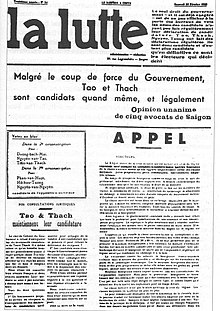

[edit]La Lutte opposed both colonial rule and the Constitutionalist Party.[8] The first issue of La Lutte was published on April 24, 1933. In the election the La Lutte grouping called its slate of candidates the 'Workers' List'. Two of the candidates of the Workers' List, Nguyen Van Tao and Tran Van Thach, were elected (there were six elected seats in total), but their election was invalidated in August 1933. Publication of La Lutte was discontinued after the election.[3][4]

Revival

[edit]With the conciliation of the charismatic and independent revolutionary figure of Nguyen An Ninh, the collaboration was revived in October 1934. The editorial line agreed between the Party group and the Trotskyists was "struggle oriented against the colonial power and its constitutionalist allies, support of the demands of workers and peasants without regard to which of the two groups they were affiliated with, diffusion of classic Marxist thought, [and] rejection of all attacks against the USSR and against either current.".[9] The editorial board consisted of Nguyen An Ninh, Le Van Thu, Tran Van Thach (left-wing nationalists), Nguyen Van Tao, Duong Bach Mai, Nguyen Van Nguyen, Nguyen Thi Luu (Communist Party), and Ta Thu Thau, Ho Huu Tuong, Phan Van Huu, Phan Van Chang and Huynh Van Phuong (Trotskyists).[3] Edgar Ganofsky, a Frenchman from the island of Réunion who identified with the coolies among whom he lodged, lent his French citizenship and experience in publishing his own paper La Voix Libre [The Free Voice], in assuming official managerial responsibility for the newspaper.[10]

The united front formed around La Lutte ran various campaigns and participated in elections. In the March 1935 Cochinchina assembly election, albeit with restricted suffrage and government interference, leftist candidates obtained 17% of the votes. There was a joint La Lutte candidate slate for the May 1935 municipal election, and Tran Van Thach, Nguyen Van Tao, Ta Thu Thau and Duong Bach Mai were elected. The election of the latter three was, however, invalidated.[3] Moreover, the election was preceded by a controversy within the La Lutte alliance regarding the candidature of Duong Bach Mai, a Communist Party leader. He was labelled 'reformist' by Trotskyists, but defended by Ta Thu Thau.[11] In late 1936 and 1937 the grouping organized various strikes.[3]

La Lutte gave a large amount of attention to political prisoners held by the French colonial regime and campaigned for an amnesty for political prisoners.[3] Prisoners' protests were frequently reported in the pages of La Lutte.[12]

Unwilling to further muzzle criticism of the "Stalinists" and the Communist Party, early in 1936 Ho Huu Tuong and Ngo Van withdrew from La Lutte. With the League of Internationalist Communists for the Construction of the Fourth International they began publication of their own weekly "organ of proletarian defence and Marxist combat," Le Militant.[13]

Division over the Popular Front

[edit]The Communist Party members and the remaining Trotskyists around Ta Thu Thau divided in their response to the new Popular Front government in France, which had the support of the French Communist Party and the blessing of Moscow.[14] Thau argued that the leftward shift in the French national Assembly had brought little change. He and other labour activists continued to be arrested, and preparations for a popular Indo-China congress in response to the government's promise of colonial consultation had been suppressed.[15]

By 1937 the Ta Thu Thau tendency had become the dominant force in La Lutte.[16] In May 1937 the Communist Party launched a new newspaper of its own, L'Avant Garde ('The Vanguard'), in which the Trotskyists were attacked. The split in La Lutte was finalized on June 14, 1937, when the Communist Party refused to support Thau's motion against the Popular Front government.[17] The Trotskyists publicly blamed the French Communist Party for the break.[18]

The fate of the lutteurs

[edit]With La Lutte now an openly Trotskyist paper, and with a Vietnamese-language edition (Tranh Dau),[19] Tạ Thu Thâu led a "Workers' and Peasants' Slate" into victory over both the Constitutionalists and the PCI's Democratic Front in the April 1939 Cochinchina Council elections. The partisans of the Fourth International, however, may have triumphed for reasons relatively mundane. In spite of their radical programme, the election could be understood, at least in part, as a tax payers' protest against the new national defence levy that the Communist Party, in the spirit of Franco-Soviet accord, had felt obliged to support.[20]

Informing him of their "shining victory" over "the shameful coalition of the bourgeois of all types and the Stalinists", Phan Van Hum, Tran Van Thach, Ta Thu Thau and the group La Lutte "sent their affectionate Bolshevik-Leninist salutations" to Trotsky.[21]

With the outbreak of World War II in September 1939 Communists of every stripe were repressed. The French law of September 26, 1939, which legally dissolved the French Communist Party, was applied in Indochina to Stalinists and Trotskyists alike. The Indochinese Communist Party and the Trotskyist groups were driven completely underground.

In the general uprising in Saigon against the restoration of the French in September 1945, lutteurs formed a workers militia. The Trotskyist Ngô Văn records two hundred of these being "massacred" by the French, October 3, at the Thi Nghe bridge. Caught between the French and the Communist Viet Minh, there would be few survivors. Tạ Thu Thâu had been captured and executed by the Viet Minh some weeks before.[22] Dương Bạch Mai, who had been among the Stalinists on the original editorial board of La Lutte,[23] led Vietminh security in hunting down his former colleagues on the paper. In October they captured and executed among others Nguyen Van Tien, the former managing editor, and Phan Văn Hùm.[24] Edgar Ganovsky, after three years in colonial prisons, died in 1943.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ Steinberg, David Joel. In Search of Southeast Asia; A Modern History. New York: Praeger Publishers, 1971. p. 322

- ^ Bousquet, Gisèle L. Behind the Bamboo Hedge: The Impact of Homeland Politics in the Parisian Vietnamese Community. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1991. pp. 34-35

- ^ a b c d e f Alexander, Robert J. International Trotskyism, 1929-1985: A Documented Analysis of the Movement. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991. pp. 961-962

- ^ a b Trager, Frank N (ed.). Marxism in Southeast Asia; A Study of Four Countries. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1959. p. 134

- ^ McConnell, Scott. Leftward Journey: The Education of Vietnamese Students in France, 1919-1939. New Brunswick, U.S.A.: Transaction Publishers, 1989. p. 145

- ^ Daniel Hemery Revolutionnaires Vietnamiens et pouvoir colonial en Indochine. François Maspero, Paris. 1975, p. 63

- ^ McHale, Shawn Frederick. Print and Power: Confuciansim, Communism, and Buddhism in the Making of Modern Vietnam. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2004. p. 126

- ^ Quinn-Judge, Sophie. Ho Chi Minh: The Missing Years ; 1919 - 1941. Berkeley [u.a.]: University of California Press, 2002. p. 200

- ^ Hémery, Révolutionaires vietnamiens, p. 63

- ^ Van, Ngo (2010). In the Crossfire: Adventures of a Vietnamese Revolutionary. AK Press. pp. 176–177. ISBN 978-1-84935-013-6.

- ^ Trager, Frank N (ed.). Marxism in Southeast Asia; A Study of Four Countries. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1959. p. 139

- ^ Zinoman, Peter. The Colonial Bastille: A History of Imprisonment in Vietnam, 1862 - 1940. Berkeley [u.a.]: University of California Press, 2001. p. 231

- ^ Văn (2010), pp. 168-169

- ^ Alexander, Robert J. International Trotskyism, 1929-1985: A Documented Analysis of the Movement. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991. p. 964

- ^ Hemery Revolutionnaires Vietnamiens, p. 388

- ^ Dunn, Peter M. The First Vietnam War. London: C. Hurst, 1985. p. 7

- ^ Trager, Frank N (ed.). Marxism in Southeast Asia; A Study of Four Countries. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1959. p. 142

- ^ Quinn-Judge, Sophie. Ho Chi Minh: The Missing Years ; 1919 - 1941. Berkeley [u.a.]: University of California Press, 2002. p. 227

- ^ Patti, Archimedes L.A. Why Viet Nam?: Prelude to America's Albatross. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980. p. 522

- ^ McDowell, Manfred (2011). "Sky Without Light: A Vietnamese Tragedy". New Politics. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ^ "La Lutte: Letter to Trotsky". www.marxists.org. 18 May 1939. Retrieved 2023-06-18.

- ^ Văn (2010), p. 131, p. 162

- ^ Alexander, Robert J. International Trotskyism, 1929-1985: A Documented Analysis of the Movement. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991. pp. 961-962

- ^ Văn (2010), p. 157

- ^ Văn (2010), p. 177