Ikki Kita

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

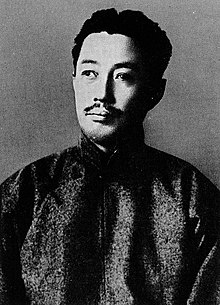

Kita Ikki | |

|---|---|

Kita Ikki (北 一輝, Kita Ikki) | |

| Born | Kita Terujirō (北 輝次郎) 3 April 1883 |

| Died | 19 August 1937 (aged 54) |

| Cause of death | Execution by firing squad |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Education | Waseda University (no degree) |

| Occupation | Author |

| Notable work | An Outline Plan for the Reorganization of Japan (日本改造法案大綱, Nihon Kaizō Hōan Taikō) 1919 |

| Children | 1 (adopted child, son of T'an Jen-feng, who was a Chinese Revolutionary) |

| Era | 20th-century philosophy |

| Region | Eastern philosophy |

| School | Japanese nationalism |

| Language | Japanese |

Main interests | Political philosophy |

| Part of a series on |

| Statism in Shōwa Japan |

|---|

|

Ikki Kita (北 一輝, Kita Ikki, 3 April 1883 – 19 August 1937; real name: Kita Terujirō (北 輝次郎)) was a Japanese author, intellectual and political philosopher who was active in early Shōwa period Japan. Drawing from an eclectic range of influences, Kita was a self-described socialist who has also been described by some as the "ideological father of Japanese fascism",[1] though this has been highly contested, as his writings touched equally upon pan-Asianism, Nichiren Buddhism, fundamental human rights and egalitarianism and he was involved with Chinese revolutionary circles. While his publications were invariably censored and he ceased writing after 1923, Kita was an inspiration for elements on the far-right of Japanese politics into the 1930s, particularly his advocacy for territorial expansion and a military coup. The government saw Kita's ideas as disruptive and dangerous; in 1936 he was arrested for allegedly joining the failed coup attempt of 26 February 1936 and executed in 1937.

Background

[edit]Kita was born on Sado Island, Niigata Prefecture, where his father was a sake merchant and the first mayor of the local town. Sado island, which used to be used for penal transportation, had a reputation for being rebellious, and Kita took some pride in this. He studied Chinese classics in his youth and became interested in socialism at the age of 14. In 1900 he began publishing articles in a local newspaper criticizing the Kokutai ("Structure of State") theory. This led to a police investigation which was later dropped. In 1904 he moved to Tokyo, where he audited lectures at Waseda University, but never earned a university degree. He met many influential figures in the early socialist movement in Japan but quickly became disillusioned; the movement was, according to him, full of "opportunists".[2]

Ideology

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| Fascism |

|---|

|

At age 23, Kita published his first book in 1906 after one year of research – a massive 1,000-page political treatise titled The Theory of Japan's National Polity and Pure Socialism (国体論及び純正社会主義).[3] In it, he criticized the government ideology of Kokutai and warned that socialism in Japan was in danger of degenerating into a watered down, simplified form of itself because socialists were too keen on compromising.[nb 1]

Theories of Japanese Politics

[edit]Kita first outlined his philosophy of nationalistic socialism in his book The Theory of Japan's National Polity and Pure Socialism, also known as Kokutairon and Pure Socialism (国体論及び純正社会主義, Kokutairon oyobi Junsei Shakaishugi), published in 1906, where he criticized Marxism and class conflict-oriented socialism as outdated. He instead emphasized an exposition of the evolutionary theory in understanding the basic guidelines of societies and nations. In this book Kita explicitly promotes the platonic state of authoritarianism, emphasizing the close relationship between Confucianism and the "from above" concept of national socialism stating that Mencius is the Plato of the East and that Plato's concept of organizing a society is far preferable to Marx's.

Engagement with the Chinese Revolution

[edit]Kita's second book is titled An Informal History of the Chinese Revolution (支那革命外史 Shina Kakumei Gaishi) and is a critical analysis of the Chinese Revolution of 1911.

Attracted to the cause of the Chinese Revolution of 1911, Kita became a member of the Tongmenghui (United League) led by Song Jiaoren. He traveled to China to assist in the overthrow of the Qing dynasty.

However, Kita was also interested in the far-right. The right-wing, ultranationalist Kokuryūkai (Amur River Association/Black Dragon Society), was founded in 1901. Kita—who held views on Russia and Korea remarkably similar to those espoused by the Kokuryukai—was sent by that organization as a special member, who would write for them from China and send reports on the ongoing situation at the time of the 1911 Xinhai revolution.[7]

By the time Kita returned to Japan in January 1920, he had become very disillusioned with the Chinese Revolution, and the strategies offered by it for the changes he envisioned. He joined Ōkawa Shūmei and others to form the Yuzonsha (Society of Those Who Yet Remain), an ultranationalist and Pan-Asianist organization, and devoted his time to writing and political activism. He gradually became a leading theorist and philosopher of the right-wing movement in pre-World War II Japan.[citation needed]

Toward the Reorganization of Japan

[edit]His last major book on politics was An Outline Plan for the Reorganization of Japan (日本改造法案大綱, Nihon Kaizō Hōan Taikō). First written in Shanghai but banned in 1919, the book was published by Kaizōsha, which was the publisher of the magazine Kaizō, in 1923, which was censored by the Government. The common theme to his first and last political works is the notion of a national policy (Kokutai),[nb 2] through which Japan would overcome a coming national crisis of economics or international relations, lead a united and free Asia and unify culture of the world through Japanized and universalized Asian thoughts in order to be prepared for the appearance of the sole superpower which would be inevitable for the future world peace. It thus contained aspects associated with the doctrine of pan-Asianism.

According to his political program, a coup d'état would be necessary as to impose a more-or-less state of emergency regime based on a direct rule by a powerful leader. Due to the respect that the Emperor enjoyed in the Japanese society,[nb 3] Kita identified the sovereign as the ideal person to suspend the Constitution, organize a council created by the Emperor and radically reorganize the Cabinet and the Diet, whose members would be elected by the people, to be free of any "malign influence", which would make the true meaning of the Meiji Restoration clear. The new "National Reorganization Diet" would amend the Constitution according to the draft proposed by the Emperor, impose limits on individual wealth, private property, and assets of companies, and establish national entities directly and unitedly operated by the Government like the Japanese Government Railways. Land reform would be enacted; all urban land would be changed to municipal property. The new state would abolish the kazoku peerage system, the House of Peers and all but fundamental taxes, guaranteeing male suffrage, freedom, the right to property, the right to education, labor rights and human rights. While maintaining the Emperor as the representative of the people, privileged elites would be displaced[nb 4] and the military further empowered so as to strengthen Japan and enable it to liberate Asia from Western imperialism.[8]

Kita asserted Japan's right as an "international Proletariat" to conquer Siberia of Far East and Australia,[nb 5] whose peoples would be granted the same rights as Japanese would,[nb 6] because social issues in Japan would never be solved if problems of international distribution were not decided. This was termed the Shōwa Restoration.[9]

In its historical prospect Kita's political program was for creating a state socialism in a fascistic oriented "socialism from above",[nb 7] as a tool to unite and strengthen Japanese society. Japan's overseas actions were meant to focus on achieving the independence of India and the maintenance of the Republic of China to stop the partition of China like Africa, in the name of Asian unity.[nb 8] Another goal of his program was to build the great Empire which included Korea, Taiwan, Sakhalin, Manchuria, the Russian Far East and Australia.

On foreign policy

[edit]He wrote a “petition” on foreign policy after the Mukden Incident. He strongly opposed a war against America, which was a popular opinion at that time, because the British Empire would join the war and the Japanese navy would not defeat them. He also thought China and the Soviet Union would join the war on the side of America. His proposal was that Japan should form an alliance with France and combat the Soviet Union. He thought that an alliance with France would contain the British Empire, and that Japan and France shared Anti-Russian sentiment because the Russian Empire had not paid massive debt to France.

Critical reception

[edit]Walter Skya notes that in On the Kokutai and Pure Socialism, Kita rejected the Shintoist view of far-right nationalists such as Hozumi Yatsuka that Japan was an ethnically homogeneous "family state" descended through the Imperial line from the goddess Amaterasu Omikami, emphasizing the presence of non-Japanese in Japan since ancient times. He argued that along with the incorporation of Chinese, Koreans, and Russians as Japanese citizens during the Meiji period, any person should be able to naturalize as a citizen of the empire irrespective of race, with the same rights and obligations as ethnic Japanese. According to Kita, the Japanese empire couldn't otherwise expand into areas populated by non-Japanese people without having to "exempt them from their obligations or ... expel them from the empire."[10] One of his religious inspirations was the Japanized Lotus Sutra.

His younger brother Reikichi Kita, political philosopher who studied for five years in the US and Europe and was a member of the House of Representatives, later wrote that Kita had been familiar with Kiichiro Hiranuma, then Chief of the Supreme Court of Justice, and in his paper in 1922 he had fiercely condemned Adolph Joffe, then Soviet Russian diplomat to Japan.[11]

This eclectic blend of imperialism, socialism and spiritual principles[nb 9] is one of the reasons why Kita's ideas have been difficult to understand in the specific historical circumstances of Japan between the two world wars. Some[who?] have argued that this is also one of the reasons why it is hard for the historians to agree on Kita’s political stance, though Nik Howard takes the view that Kita's ideas were actually highly consistent ideologically throughout his career, with relatively small shifts in response to the changing reality he faced at any given time.[12]

Esperanto proposal

[edit]In 1919 Kita advocated that the Empire of Japan should adopt Esperanto. He foresaw that 100 years after its adoption the language would be the only tongue spoken in Japan proper and the vast territory conquered by it according to the natural selection theory, making Japanese the Sanskrit or Latin equivalent of the Empire. He thought that the writing system of Japanese is too complicated to impose on other peoples, that romanization would not work and that English, which was taught in the Japanese education system at that time, was not mastered by Japanese at all. He also asserted that English is poison to Japanese minds as opium destroyed Chinese people, that the only reason it did not destroy Japanese yet was that German had more influence than English and that English should be excluded from the country. Kita was inspired by several Chinese anarchists he befriended who had called for the substitution of Chinese for Esperanto at the beginning of the twentieth century.[13][14]

Arrest and execution

[edit]

Kita's Outline Plan, his last book, exerted a major influence on a part of the Japanese military—especially in the Imperial Japanese Army factions who participated in the failed coup of 1936. After the coup attempt, Kita was arrested by the Kempeitai for complicity, tried by a closed military court, and executed.[15]

In fiction

[edit]- Ikki Kita is a major character in the historical fantasy novel Teito Monogatari by Hiroshi Aramata. In the novel, he is also a Buddhist shaman who is deeply devoted to the Kegon Sutras.

- Kita appears in manga artist Motoka Murakami's Shōwa-era epic Ron.

- Kita is a secondary character in Osamu Tezuka's Ikki Mandara.

- Kita (portrayed by Hiroshi Midorigawa) figures in the plot of Seijun Suzuki's 1966 film Fighting Elegy.

- Yoshida Yoshishige's film Coup d'État (1973) of Japanese New Wave cinema depicts Kita's life during the 1920s up to his death.

- In Yukio Mishima’s novel Spring Snow, Kita’s writings figure in the reading of the most intellectual of the main characters, Honda.

- As for Honda, he could never be quite at ease unless there were books within easy reach. Among those now at hand was a book he had been lent in secret by one of the student houseboys, a book proscribed by the government. Titled Nationalism and Authentic Socialism, it had been written by a young man named Terujiro Kita, who at twenty-three was looked upon as the Japanese Otto Weininger. However, it was rather too colorful in its presentation of an extremist position, and this aroused caution in Honda’s calm and reasonable mind. It was not that he had any particular dislike of radical political thought. But never having been really angry himself, he tended to view violent anger in others as some terrible, infectious disease. To encounter it in their books was intellectually stimulating, but this kind of pleasure gave him a guilty conscience.[16]

See also

[edit]- Kōtoku Shūsui

- Sadao Araki

- Seigō Nakano

- Socialist thought in Imperial Japan

- Japanese dissidence in 20th-century Imperial Japan

- Japanese nationalism

- Japanese intervention in Siberia

- Rice riots of 1918

- Third Position

Notes

[edit]- ^ As analysed by, for example, Hal Draper, who contrasts this current to its opposite, "socialism from above";[4] however, Japanese labor historian Stephen Large also employs this conceptual couplet of "socialism from above and from below" in a book on the inter-war Japanese socialist movement.[5] John Crump's research on the origins of Japanese socialism essentially argues that none of the early Japanese socialists of the late Meiji period consistently broke with capitalist socioeconomic and political relations in theory or in practice.[6]

- ^ Rather, he criticized conflicts between advocates of kokutai and advocates of Western ideas for they did not understand social change and evolution of Japan, and he thought Japan had been a democracy (minsyukoku) led by the Emperor, which was not directly imported from the Western, since the Meiji Restoration, which was a movement to be liberated from servitude to the Shogun and the Daimyo. In the introduction he also wrote “Japanese nationals surely need to understand the justice of the nation and human rights of equality”.

- ^ His main purpose of this coup was to clarify the meaning and the principle of the Emperor, who is the representative of the people.

- ^ They were the Meiji oligarchy, Zaibatsu (Concerns), Gunbatsu (Military Factions), landlords, the Oriental Development Company and so on.

- ^ He thought this was analogous to domestic class conflict Vladimir Lenin actually had done in Russia, which was rationalized.

- ^ He believed that this would be a model of racial equality and that the only one who could govern unity between the culture of the East and that of the West was the Empire of Japan.

- ^ He stressed that a coup is not for conservative autocracy, it is the direct expression of the general will, and that the general will should be expressed by the fusion of the Emperor and the people, not the authorities.

- ^ He also mentioned there was anti-Japanese sentiment in China and argued Japan needed to deprive the UK of Hong Kong and build a naval base there instead of Qingdao, which had so many people that Shandong coolies were exported.

- ^ Masking a deeper consistency from the time of his early articles: he calls for Japanese expansion to Korea and Manchuria, as well as for militant war with Russia and Britain—whom he dubs "landlord nations", with Japan a so-called "proletarian nation".

References

[edit]- ^ Maruyama, Masao (1956). Thoughts and Behaviour in Modern Japanese Politics (Ivan Morris ed.). London: Oxford University Press. p. 165.

- ^ Wilson, George M. Radical nationalists in Japan: Kita Ikki 1883-1937. Harward University Press, Cambridge, 1969

- ^ Koschmann, J. Victor (1978). Authority and the Individual in Japan. University of Tokyo Press.

- ^ Draper, Hal (1963). The Two Souls of Socialism: socialism from below v. socialism from above. New York: Young People's Socialist League. OCLC 9434175.

- ^ Large, Stephen S. (1981). Organized Workers and Socialist Politics in Interwar Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-23675-1. OCLC 185302691.

- ^ Crump, John (1983). The Origins of Socialist Thought in Japan. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-58872-4. OCLC 9066549.

- ^ Wilson, George Macklin (1969). Radical Nationalist in Japan: Kita Ikki, 1883–1937. Harvard East Asian Series. Vol. 37. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. OCLC 11889.

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 438 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 437 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ Walter Skya, Japan's Holy War: the Ideology of Radical Shinto Ultranationalism pp.123–125 ISBN 978-0822344230

- ^ Reikichi Kita (Ja) (1951). Plofile of Heikichi Ogawa (Japanese version) p.p.55, 61. Japan and Japanese (Ja) 2(3).

- ^ Howard, Nik (Summer 2004). "Was Kita Ikki a Socialist?". The London Socialist Historians Group Newsletter. No. 21. London: London Socialist Historians Group. Archived from the original on 24 April 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2010.

- ^ Hiroyuki Usui, A Japanese ultranationalist and Chinese anarchists: unknown forerunners of "sennaciismo" in the East, Conference on Esperanto Studies,

- ^ (eo) Hiroyuki Usui, Prelego pri Esperanto por japanoj en Pekino (Lecture about Esperanto for Japanese in Beijing), China.Espernto.org.cn, 29 January 2013.

- ^ James L. McClain, Japan: A Modern History p 439 ISBN 0-393-04156-5

- ^ Mishima, Yukio. Spring Snow (1968). English translation by Michael Gallagher, 1972. New York City: Washington Square Press, 1975. Chapter 35, p. 239.

- Ikki Kita(北一輝) (2014). 日本改造法案大綱 (An Outline Plan for the Reorganization of Japan). Tokyo: CHUOKORON-SHINSHA INC. (中公文庫). ISBN 978-4-12-206044-9. (in Japanese)

Further reading

[edit]- Saaler, Sven; Szpilman, Christopher W.A. (2011). Pan-Asianism: A Documentary History. Lanham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4422-0596-3.

- Tankha, Brij (2006). Kita Ikki And the Making of Modern Japan: A vision of empire. Folkestone, Kent: Global Oriental. ISBN 978-1-901903-99-7. OCLC 255304652.

- Kamal, Niraj (2003). Arise, Asia! Respond to white peril. Delhi: Wordsmiths. ISBN 978-81-87412-08-3. OCLC 51586701.

External links

[edit]- Martial Law on YouTube —a movie about the life and death of Kita Ikki

- 1883 births

- 1937 deaths

- Japanese writers

- Japanese Esperantists

- Japanese revolutionaries

- 20th-century executions for treason

- People from Sado, Niigata

- 20th-century executions by Japan

- Far-right politics in Japan

- Third Position

- Executed Japanese people

- Executed activists

- Executed revolutionaries

- Executed writers

- People executed for treason against Japan

- People executed by Japan by firing squad

- Civilians who were court-martialed

- Pan-Asianists

- 20th-century Japanese philosophers

- Meiji socialists