Kīlauea Iki

19°24.833′N 155°14.785′W / 19.413883°N 155.246417°W

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (January 2012) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

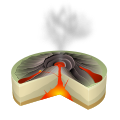

Kīlauea Iki is a pit crater that is next to the main summit caldera of Kīlauea on the island of Hawaiʻi in the Hawaiian Islands. It is known for its eruption in 1959 that started on November 14 and ended on December 20, producing lava fountaining up to 1900 feet and a lava lake in the crater. Today, the surface of the lava lake has cooled and it is now a popular hiking destination to view the aftermath of an eruption.

15th-century eruption

[edit]Lava tubes associated with Kīlauea Iki are responsible for the vast ʻAilāʻau eruption, carbon 14 dated from c. 1445 and erupting continuously for approximately 50 years, which blanketed much of what is now Puna District with 5.2 ± 0.8 km3 of basalt lava.[1]

1868 eruption

[edit]Kilauea Iki experienced a minor eruption in 1868, which covered the floor of the crater in a thin layer of basalt.[2] This eruption was preceded by the great Ka'ü earthquake of 1868, a magnitude 7.9 earthquake that caused extensive damage on the island and resulted in collapses of the wall in Kilauea's summit caldera, withdrawal of lava from the summit caldera, and the brief eruption in Kilauea Iki.[3]

1959 eruption

[edit]

At 8:08 pm on November 14, 1959, an eruption began at the summit of Kilauea in the Kilauea Iki crater after several months of increased seismicity and deformation.[4] Over the next month, the crater experienced 17 eruption episodes, each one (except for the last) beginning with lava fountaining and ending with lava drainback.[5][6] After the first episode, which lasted 7 days, most of the remaining episodes were less than 24 hours, with the shortest (14th episode) lasting less than 2 hours.[4][3] Volcanic ejecta from the main fissure on the western side of the crater formed the 70 meter high Pu'u Pua'i tephra cone (Hawaiian for 'gushing hill').[5][7] On December 11, 1959, at the end of the 8th episode, the lava lake formed in the crater reached its greatest volume (58 million cubic yards) and depth (414 feet).[4] The final volume and depth of the lava lake after the end of the eruption on December 20 was approximately 50 million cubic yards and 365 feet, respectively.[4][3] In 1988, a drilling project of Kilauea Iki showed that the lava lake depth was deeper than expected by 50-90 feet.[2] This was likely due to the crater floor collapsing during the 1959 eruption.[2][3]

Precursors

[edit]Early warning signs of the impending eruption included outward tilting at the summit region and increased seismicity.[4][3][8] Tiltmeter measurements between November 1957 and February 1959 indicated that magma was migrating towards the summit, causing swelling of the ground surface.[4] Swelling ceased and deflation of the summit began after several earthquakes occurred on February 19, 1959.[4] Slow deflation continued until a swarm of earthquakes in mid-August 1959 led to resumption of rapid swelling that continued until the eruption in November.[4][8] Most of these earthquake swarms were at a depth of 40-60 km and likely related to upward magma movement from the mantle.[3] By early November, more than 1,000 earthquakes were being recorded each day and tiltmeter measurements indicated swelling 3 times faster than previous rates.[4][8]

Lava fountaining

[edit]

Lava fountaining is characteristic of Hawaiian eruptions and the 1959 eruption of Kilauea Iki produced some of the highest lava fountains ever observed in Hawaii.[3][9] At the beginning of the eruption, the fountain height was only 30 m, but this increased over the next several days to between 200 and 300 m.[5] On November 21, the fountain went from 210 meters tall to a few gas bubbles in less than 40 seconds.[5] Some of the fountains were extraordinarily high, with the 15th episode producing a fountain reaching nearly 580 m (1,900 ft), among the highest ever recorded.[5][9] After the end of each eruption episode, lava drained back into the vent which may have acted as a coolant for the underlying material, resulting in the triggering of the next episode of lava fountaining.[10]

Lava drainback

[edit]

Lava drainback is common during eruptions at Kilauea and occurs when magma erupts at the surface, forming a lava lake and then draining back below ground.[11][8] During the Kilauea Iki eruption, the level of the lava lake would rise until it reached the erupting vent partway up the crater wall, where lava drainback would begin.[6][4][11] The first episode had 31 million cubic meters of lava flow into Kīlauea Iki with 1 million cubic meters draining back.[8] During the following episodes, a total of 71 million cubic meters of lava was ejected during a month-long eruption that stopped on December 20, 1959.[8] Only 8 million cubic meters of lava remained, with 63 million cubic meters of lava draining back into the Kīlauea magma reservoir.[8] Often the lava drainback had a higher rate of flow than the eruptions.[8]

With every filling and draining of the lava lake, a 'black ledge' was formed along the rim of the crater which marked the level of the lava lake during each eruption episode.[6][8] During lava drainbacks, a giant counter-clockwise whirlpool would form.[4]

Magma mixing

[edit]Samples collected from the first episode of the eruption were composed of two different kinds of magma.[3][12] The first variant was identical to previous magmas erupted in the 1954 Kilauea caldera eruption and the second variant had a composition different from anything seen at previous eruptions, with a high ratio of CaO to MgO.[3] Subsequent eruption episodes produced samples that were a mixture of the two variants plus some additional amount of olivine.[12] The reason for two different magma compositions may be two magma storage areas beneath Kilauea Iki that had higher olivine concentrations at the bottom.[12] At the beginning of the eruption, both magma sources provided material to the surface, while later eruption episodes at the single vent on the west side of the caldera contained a mixture of the two magmas.[12][3] Additionally, the later eruption episodes were sourced from deeper sections of the magma chambers, resulting in higher concentrations of olivine.[12][10]

Tourism

[edit]Drivers may view Kīlauea Iki from either a lookout point or the trailhead parking lot. Guests can hike across Kīlauea Iki by descending from Byron Ledge, which overlooks the crater. The trail crosses the floor of the crater, which once was a lake of lava. Even after 50 years, the parts of the surface are still warm to the touch. Rainwater seeps into the cracks and makes contact with the extremely hot rock below and steam is emitted from various surface cracks. The steam and some rocks are hot enough to cause serious burns.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Kilauea summit overflows: Their ages and distribution in the Puna District, Hawai'i - USGS

- ^ a b c Helz, Rosalind Tuthill (1993). "Drilling report and core logs for the 1988 drilling of Kilauea Iki lava lake, Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii, with summary descriptions of the occurrence of foundered crust and fractures in the drill core". Open-File Report. doi:10.3133/ofr9315.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Wright, Thomas L.; Klein, Fred W. (2014). "Two hundred years of magma transport and storage at Kīlauea Volcano, Hawai'i, 1790-2008". Professional Paper. Reston, VA. p. 258. doi:10.3133/pp1806.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Richter, D. H.; Eaton, J. P.; Murata, K. J.; Ault, W. U.; Krivoy, H. L. (1970). "Chronological narrative of the 1959-60 eruption of Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii". Professional Paper. doi:10.3133/pp537E. ISSN 2330-7102.

- ^ a b c d e Stovall, Wendy K.; Houghton, B. F.; Gonnermann, H.; Fagents, S. A.; Swanson, D. A. (2011-07-01). "Eruption dynamics of Hawaiian-style fountains: the case study of episode 1 of the Kīlauea Iki 1959 eruption". Bulletin of Volcanology. 73 (5): 511–529. Bibcode:2011BVol...73..511S. doi:10.1007/s00445-010-0426-z. ISSN 1432-0819. S2CID 35463320.

- ^ a b c Stovall, W. K.; Houghton, Bruce F.; Harris, Andrew J. L.; Swanson, Donald A. (2009-02-13). "Features of lava lake filling and draining and their implications for eruption dynamics". Bulletin of Volcanology. 71 (7): 767–780. Bibcode:2009BVol...71..767S. doi:10.1007/s00445-009-0263-0. ISSN 0258-8900. S2CID 53413719.

- ^ Gailler, Lydie; Kauahikaua, Jim (2017). "Monitoring the cooling of the 1959 Kīlauea Iki lava lake using surface magnetic measurements". Bulletin of Volcanology. 79 (6): 40. Bibcode:2017BVol...79...40G. doi:10.1007/s00445-017-1119-7. ISSN 0258-8900. S2CID 134828463.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Eaton, Jerry; Richter, Donald; Krivoy, Harold. "Cycling of magma between the summit reservoir and Kilauea Iki lava lake during the 1959 eruption of Kilauea volcano" (PDF). U.S. Geological Survey Professional Paper. 1350.

- ^ a b Stovall, Wendy K.; Houghton, Bruce F.; Hammer, Julia E.; Fagents, Sarah A.; Swanson, Don A. (2011-09-27). "Vesiculation of high fountaining Hawaiian eruptions: episodes 15 and 16 of 1959 Kīlauea Iki". Bulletin of Volcanology. 74 (2): 441–455. doi:10.1007/s00445-011-0531-7. ISSN 0258-8900. S2CID 55205736.

- ^ a b Sides, I.; Edmonds, M.; Maclennan, J.; Houghton, B. F.; Swanson, D. A.; Steele-MacInnis, M. J. (2014-08-15). "Magma mixing and high fountaining during the 1959 Kīlauea Iki eruption, Hawai'i". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 400: 102–112. Bibcode:2014E&PSL.400..102S. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2014.05.024. ISSN 0012-821X.

- ^ a b Wallace, Paul J.; Anderson Jr., Alfred T. (1998-03-11). "Effects of eruption and lava drainback on the H 2 O contents of basaltic magmas at Kilauea Volcano". Bulletin of Volcanology. 59 (5): 327–344. Bibcode:1998BVol...59..327W. doi:10.1007/s004450050195. ISSN 0258-8900. S2CID 129162203.

- ^ a b c d e WRIGHT, THOMAS L. (1973-03-01). "Magma Mixing as Illustrated by the 1959 Eruption, Kilauea Volcano, Hawaii". GSA Bulletin. 84 (3): 849–858. Bibcode:1973GSAB...84..849W. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1973)84<849:MMAIBT>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0016-7606.

External links

[edit]- Summit Eruption of Kīlauea Volcano, in Kīlauea Iki Crater

- US Department of Defense film of the 1959 volcano eruption of Kilauea Iki Crater

- The short film "Volcano Eruptions (1959)" is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive.