Kere (famine)

| Kere | |

|---|---|

| Country | Madagascar |

| Location | Southern Madagascar |

| Period | Ongoing[1][2] |

| Causes | drought, deforestation, pests and diseases including locusts and cochineal, lawlessness |

The Kere (also Kéré; from the Antandroy dialect of Malagasy, literally meaning 'starved to death'[2]) is a recurrent famine affecting Madagascar's Deep South. Since 1896, sixteen famines have been recorded.[1][2] The average gap between Kere events is two years.[2] The famine, affecting a region of approximately 50,000 square kilometres (19,000 sq mi) from the Mandrare River to the Onilahy River, kills thousands of people per year and contributes to the severe poverty of the region—97% of the territory of the Kere are classified as "very poor" by Madagascar's Institut national de la statistique.[2] Though aid and interventions aimed at alleviating the Kere have taken place for decades, the famine has been resistant and is worsening. In the Kere zone, whose residents are called o'ndaty, non-Kere periods are called anjagne ('good' or 'peacetime').[2]

Causes

[edit]Raketa war and first great famine

[edit]

The cacti (Opuntia ficus-indica, O. tomentosa, O. robusta, O. monacantha, and O. vulgaris), introduced by a French count starting in 1769, had served as a famine food source and barrier to colonial control in southern Madagascar, enabling indigenous anti-colonial fighters (Sadiavahe, lit. 'loincloth made from wood-root') to resist the French for over two decades.[3] In the late 1920s, the spiny raketa (cactus) were decimated by cochineal insects (Dactylopius tomentosus). The cochineal effectively decimated the vegetation at a rate of 100 square kilometers per year,[3] and by 1929 a French colonial report declared the "death of the raketa". Locals refer to the cochineal as pondifoty. Between 1930 and 1933 (or 1934), a famine unfolded that killed at least half a million people, marking the beginning of the Kere. The decimation of the raketa has been ascribed as the main cause of the famine.[2][4]

It is believed that cochineal outbreak originated in November 1924, when French botanist Perrier de la Bâthie, with agreement from the governor-general Marcel Olivier, sent cochineal south to a French plantation owner to be used to clear cactus on cultivable land around Tulear which was a zone of French colonisation, but not to be used in the neighbouring Androy region in the Deep South where the economy was based on indigenous subsistence. The cochineal had been introduced to the capital, Antananarivo, the year before to little effect. It is unknown whether Perrier de la Bâthie had anticipated that the cochineal would be so virulent and propagate to other regions and decimate the raketa.[4]

According to some locals and several European writers, the French colonial authorities were actively complicit in the eradication of the raketa in the south.[4] The accusations vary considerably. Some accuse the colonial authorities of having a lack of forsight that when the insects were released into the highlands where cactus wasn't important, they would spread south with disastrous and unforseen consequences.[4] On the other hand, others accuse the French colonial authorities of releasing modified cochineal insects into healthy raketa thickets in Tongobory in November 1924 as part of a broad campaign to eliminate the raketa vegetation of the Deep South to facilitate France's complete annexation of the island,[4][3] and that the local administration mobilised to propagate the cochineal. Karen Middleton, writing in the Journal of Southern African Studies, states that "little if any evidence has been published to substantiate the charge".[4] In the three decades after the famine up to independence, the colonial authorities organised the planting of Opuntia in the Deep South that was resistant to the cochineal.[4]

The first Kere is called the Marotaolagne ('scattered human skeletons') or the Tsimivositse ('uncircumcised', since some tribal subgroups ceased the practice of circumcision to commemorate the tragedy). A 2022 study of the experiences of the people of the Kere territory quoted a participant on the legacy of the introduction of the pondifoty: "Raketa forest ... provides us with supplementary food, wood to cook and to build our house, and to feed our animals—thus, when the raketa forest died, part of us also died."[2]

Deforestation

[edit]

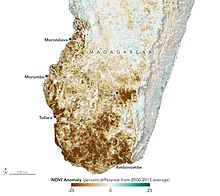

Slash-and-burn agriculture and overharvesting of charcoal and cooking wood have led to a serious crisis of deforestation in Madagascar. The land has become barren, making droughts worse and compounding seasonal famine conditions.[2]

Pests

[edit]Periodic plagues of valala (Malagasy migratory locust, Locusta migratoria capito) damage crops that survive harsh climactic conditions, as do fall armyworms (Spodoptera frugiperda). Weevils and khapra beetles devastate stored food supplies and live crops.[2]

Climate and demography

[edit]The Kere affects Madagascar's Deep South region—mostly the semiarid Mahafaly plateau, specifically the districts of Ampanihy and Betioky, and the arid sandy lands of Ambovombe, Bekily, Tsihombe, and Beloha. The affected territory experiences an annual temperature range of 22–35 °C (72–95 °F) and mean annual rainfall of 400 millimetres (16 in). Rainfall is seasonal, with up to 80 millimetres (3.1 in) a month in the rainy season of December to March, and no rainfall at all in the dry season (lasting from April to September). Dry periods that last for several years are called asaramaike ('dry rain-season').[2]

The people living in the Kere territory are overwhelmingly poor, with 97% of the population being classified as "very poor" by Madagascar's Institut National de la Statistique. The affected region is inhabited mostly by the pastoralist Mahafaly and Antandroy peoples, as well as some Antanosy and Bara, among others. 94% of the people of the Deep South are pastoralists, mostly "subsistence peasants" who rely heavily on the forest for sustenance. Zebu cattle are highly important to the culture and economy of the region. During the Kere, cattle graze on cacti. The Kere-prone zones are hotbeds of violent crime and lawless rule by dahalo, cattle-rustling bandits.[2]

Conditions and history

[edit]Residents of the Deep South describe the Kere as developing in four stages: the anjagne (peacetime); the period of scarcity of food for livestock and animals and abundance of food for humans; the period of scarcity of food for humans and abundance of food for livestock; the period of scarcity of food for both livestock and humans. The final stage is the deadliest form of Kere.[2]

As people are starved by a Kere event, some may travel on foot to search for food to bring home to their families. Many of these do not return, and many who do return find their relatives deceased or their households empty. Kere survivors report walking for up to 25 kilometres (16 mi) to find water, and some, pressed by severe dehydration and desperation, drink seawater. Some consume dirty water from puddles and boreholes. Those who consume dirty water are at great risk of waterborne illness.[2] During the first Kere, the tribal territories of the Mahafaly, Antandroy, and Antanosy peoples were filled with dead cacti, animals, and humans.[2] Tamarind pulp mixed with ashes is a common famine food consumed during the Kere.[5]

The durations of Kere events have varied. One event, called Baramino ('Digging Bar') in 1997, was felt for less than a year. Kere survivors divide historical Kere events into the categories of "ancient" (pre-1993) and recent (post-1993), with ancient Kere being generally considered more severe among locals.[2] Kere have names; due to low rates of literacy in the region, these names are used instead of years.[2]

| Number | Name | Meaning of name | Trigger | Years | Geographic scope | Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Marotaolagne ('Scattered Human Skeletons'),

Tsimivositse ('Uncircumcised') |

Marotaolagne because of the piled dead; Tsimivositse because some tribal groups stopped circumcising boys to mark the tragedy[2] | Death of raketa | 1930–1934 | Deep South | ~500,000 dead, mass migration, some groups stopped circumcision |

| 2 | Marotaolagne ('Scattered Human Skeletons') | Marotaolagne because of the piled dead[2] | El Niño, Battle of Madagascar | 1943–1946 | Deep South | ~1 million dead;[2] mass zebu sacrifice to bring back rain[5] |

| 3 | Beantane ('Many Downed') | 1955–1958 | Deep South | |||

| 4 | Menaleogne ('Red Pounder'),[2]

Zaramofo ('Distribution of Bread') |

Zaramofo because the government distributed bread as emergency aid in the region[5] | El Niño | 1970–1972 | Deep South | Triggered proclamation of Antandroy secession |

| 5 | Santira-Vy ('Iron Belt') | People had to tighten their belts powerfully because they were emaciated from starvation[5] | 1980–1982 | Deep South | Over 230,000 children dead | |

| 6 | Malalak'akanjo ('Loose Shirt') | People's shirts were loose on them because they were emaciated from starvation[5] | 1982–1983 | Deep South | ||

| 7 | Bekalapake ('Dried Cassavas') | People ate only dried cassava[5] | 1986–1987 | Deep South | ||

| 8 | Tsimitolike ('Don't Turn';[2] 'We eat without turning around'[5]) | Emphasizing the individual struggle for survival[5] | 1988–1989 | Deep South | ||

| 9 | SOS Sud ('SOS South') | 1990–1992 political crisis, El Niño | 1992–1994 | Deep South | Mass migration, first emergency management and international aid response | |

| 10 | Bekalapake ('Surrounded') | 1995–1996 | Manambovo | |||

| 11 | Baramino

('Digging Bar') |

1997–1998 | Bekily, Beloha | |||

| 12 | [No name assigned] | 2002 political crisis, El Niño, insecurity | 2004–2005 | Deep South | ||

| 13 | Bekalapake ('Red Dusty Wind') | 2009 political crisis, insecurity, El Niño | 2009–2013 | Androy, Ampanihy | Telethon in 2010[5] | |

| 14 | Bekalapake ('Wobbly Walking') | El Niño, insecurity | 2014–2017 | Tsihombe, Anjapaly, Ampanihy | ||

| 15 | [No name assigned] | El Niño, insecurity, COVID-19 pandemic, climate change (disputed) | 2020–2022 | Deep South |

2021–2022 Kere

[edit]A Kere affecting the Deep South from 2021 to 2022 was Madagascar's worst drought in 40 years.[6] In 2020, UNICEF had expressed early concerns about malnutrition in Madagascar, estimating that 42% of children under the age of five suffered from malnourishment.[7] A World Food Programme (WFP) official said in June 2021 that the situation was the second-worst food crisis he had seen in his life after the 1998 famine in Bahr el Ghazal, in present-day South Sudan.[8]

By late June 2021, the WFP reported that 75% of children had abandoned school and were begging or foraging for food. Intense dust storms were further aggravating the circumstances.[9] Humanitarian agencies also warned of water shortages. A water pipeline opened in 2019 (a joint venture of UNICEF and the government of Madagascar) did not reach far enough to provide fresh water to some parts of the south, forcing residents (mainly women) to travel more than 15 kilometers to seek water.[9]

The WFP reported on 23 June 2021 that people were eating mud and warned that millions would be affected by famine if action was not taken.[10]

On 30 June 2021, the WFP warned that a "biblical" famine was approaching in several African countries, especially in Madagascar.[11] Reports of people eating raw red cactus fruits, wild leaves and locusts for months also arose.[12] In July 2021, UK-based organization SEED Madagascar reported that people were eating "cactuses, swamp plants, and insects", while also reporting that mothers were mixing clay and fruits to feed their families. Evidence of swollen stomachs and physically stunted children were also reported by the organization as symptoms of chronic malnutrition.[13]

My compatriots in the South are suffering a heavy toll from the climate crisis in which they did not participate.

—Andry Rajoelina, president of Madagascar, July 2021.[14]

In July 2021, local media reported that out of the 2.5 million people who live in the southern districts of Madagascar, around 1.2 million were already suffering from food insecurity, while another 400,000, were in a critical situation of famine, citing concerns equal to international organizations such as climate change, COVID-19 and political instability in the country.[15]

On 14 July 2021, a government report was issued, stating that the rate of chronic malnutrition was in decline.[16] By late July 2021, however, the situation was described as "famine" by Al Jazeera[17] and Time magazine.[18]

Time magazine quoted executive director of the WFP David Beasley as describing the crisis as the first "climate change-caused" famine in modern history.[18][19] In August 2021, the food crisis was declared by the WFP to be the first famine caused by climate change and not conflict,[20][21][22] though this declaration was contradicted by a study released December 2021 by World Weather Attribution.[23]

Impact

[edit]Each Kere event has killed thousands and sparked mass migrations out of the Deep South. In 1972, a "bloody secessionist rebellion" called the rotaka followed a Kere event in the south, in part due to perceived insensitivity and apathy from Madagascar's central government to the plight of the southerners.[2] Residents of the Kere zone report a breakdown of the social fabric of their communities in times of Kere, pointing to increased youth banditry and sex work.[2] Kere events are associated with mass migration as residents flee the famine and outbreaks of dahalo crime. The first Kere cut the population of the Deep South in half, and 15% of survivors migrated from the region.[2]

Aid and response

[edit]

The first emergency management response and international aid program for the Kere was prompted by the "SOS Sud" Kere event of 1993.[2] The Malagasy government, led by then-president Albert Zafy, organized a telethon to bring aid to the starving.[24] In late 2020 the Malagasy Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development and the United Nations Development Programme launched a Green Climate Fund–financed readiness program for climate change–influenced Kere conditions, called Medium term planning for adaptation in climate sensitive sectors in Madagascar. The program had a budget of $1.3 million.[25]

2021–2022 famine

[edit]In June 2021, UNICEF initiated a "Tosika Kere" cash transfer (fiavota) program to aid o’ndaty (inhabitants of the Deep South) affected by the 2021–2022 Kere.[26]

The government of President Andry Rajoelina received backlash over the famine.[27] Rajoelina called for a "radical and lasting change" during a summit of the International Development Association in Abidjan, in Ivory Coast. He criticized those who cause climate change by saying that "my compatriots in the South are suffering a heavy toll from the climate crisis in which they did not participate." He promised more help to the south and empowerment of women.[14]

In late July 2021, the U.S. embassy further expanded its aid through USAID to more than 100,000 people in the south, providing food to children and pregnant women facing malnutrition.[28] In late August 2021, United Nations coordinator Issa Sanogo warned that the situation was still critical and that a further 500,000 children are at risk in the near future.[29] In October 2022, UNICEF contributed $23 million for children suffering from the famine.[30]

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Le "Kere", famine endémique du sud de Madagascar". Franceinfo (in French). 2021-09-21. Retrieved 2024-11-19.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa Ralaingita, Maixent I.; Ennis, Gretchen; Russell-Smith, Jeremy; Sangha, Kamaljit; Razanakoto, Thierry (2022-03-26). "The Kere of Madagascar: a qualitative exploration of community experiences and perspectives". Ecology and Society. 27 (1). doi:10.5751/ES-12975-270142. ISSN 1708-3087.

- ^ a b c Kaufmann, Jeffrey C. (2000). "Forget the Numbers: The Case of a Madagascar Famine". History in Africa. 27: 143–157. doi:10.2307/3172111. ISSN 0361-5413. JSTOR 3172111.

- ^ a b c d e f g Middleton, Karen (1999). "Who Killed 'Malagasy Cactus'? Science, Environment and Colonialism in Southern Madagascar (1924-1930)". Journal of Southern African Studies. 25 (2): 215–248. doi:10.1080/030570799108678. ISSN 0305-7070.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Holazae N. Analyse sociologique de la realite du «kere» dans la region androy (cas de la commune urbaine d’ambovombe androy). UNIVERSITY ANTANANARIVO; 2015.

- ^ Taylor, Adam (1 July 2021). "Madagascar is headed toward a climate change-linked famine it did not create". Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "L'ONU estime que le Grand Sud de Madagascar se trouve en « situation d'insécurité alimentaire grave »" [The UN considers the Great South of Madagascar to be in "a situation of serious food insecurity"] (in French). Agence Ecofin. 10 July 2021. Archived from the original on 10 July 2021. Retrieved 10 July 2021.

- ^ "UN says 400,000 are approaching starvation in Madagascar amid back-to-back droughts". France24. 26 June 2021. Archived from the original on 2 July 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Drought and famine stalk desperate Madagascar". Prevention Web. 23 June 2021. Archived from the original on 3 July 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021 – via www.preventionweb.net.

- ^ Adjetey, Elvis (23 June 2021). "Madagascar: Families eating mud due to worst drought in 40 years". Africa Feeds. Archived from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ AFP (30 June 2021). "World Food Programme warns of "biblical" famine without action". Deccan Herald. Archived from the original on 1 July 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ Cassidy, Amy; McKenzie, David; Formanek, Ingrid (23 June 2021). "Climate change has pushed a million people in Madagascar to the 'edge of starvation,' UN says". CNN. Archived from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ "Madagascar is on the brink of crisis – and a Hertfordshire charity is helping families survive". Hertfordshire Mercury. 8 July 2021. Archived from the original on 8 July 2021. Retrieved 8 July 2021.

- ^ a b "Famine dans le Sud de Madagascar : il faut "apporter un changement radical et durable", plaide Andry Rajoelina" [Famine in the South of Madagascar: we must "bring about a radical and lasting change", pleads Andry Rajoelina] (in French). Linfo. 19 July 2021. Archived from the original on 19 July 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ^ Landaz, Mahaut; Garnier, Valentin (9 July 2021). "Réchauffement climatique, Covid-19, contexte politique… A Madagascar, une famine dramatique à plusieurs facteurs" [Global warming, Covid-19, political context ... In Madagascar, a dramatic famine with several factors] (in French). Nouvelobs. Retrieved 9 July 2021.

- ^ "Le taux de prévalence de la malnutrition chronique en baisse" [Chronic malnutrition prevalence rate declining]. Madagascar Tribune (in French). 15 July 2021. Archived from the original on 15 July 2021. Retrieved 15 July 2021.

- ^ "'Nothing left': A catastrophe in Madagascar's famine-hit south". Al Jazeera. 23 July 2021. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ a b Baker, Aryn (23 July 2021). "Climate, Not Conflict. Madagascar's Famine is the First in Modern History to be Solely Caused by Global Warming". Time. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ^ Rodrigues, Charlene (22 July 2021). "Madagascar famine becomes first in history to be caused solely by climate crisis". The Independent. Archived from the original on 23 July 2021. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ^ "Madagascar is hit by the world's first climate change famine". TRT World. 27 August 2021. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ "Madagascar on the brink of climate change-induced famine". BBC. 27 August 2021. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ "'Unprecedented': Madagascar on Verge of World's First Climate-Fueled Famine". EcoWatch. 25 August 2021. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 28 August 2021.

- ^ Borenstein, Seth (December 1, 2021). "Study: Climate change not causing Madagascar drought, famine". AP NEWS. Archived from the original on 15 December 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2023.

- ^ Randriamady, Hervet (May 2016). "Malnutrition: an endless battle in Madagascar". UC Berkeley International & Executive Programs. Retrieved 2024-10-23.

- ^ "New Readiness Programme launched in Madagascar to support adaptation planning | UNDP Climate Change Adaptation". www.adaptation-undp.org. 2020-12-17. Retrieved 2024-10-24.

- ^ Rakotoarison, Solofonirina Claudia (2 June 2021). "The Tosika Kere programme in Southern Madagascar". UNICEF.

- ^ "Une journaliste interpelle Andry Rajoelina sur la famine dans le sud de Madagascar" [Journalist challenges Andry Rajoelina on famine in southern Madagascar]. Koolsaina (in French). 21 June 2021. Archived from the original on 11 July 2021. Retrieved 11 July 2021.

- ^ "100,000 People in Southern Madagascar to Benefit from New U.S. Government Assistance". U.S. embassy in Madagascar. 26 July 2021. Archived from the original on 26 July 2021. Retrieved 26 July 2021.

- ^ Bhuckory, Kamlesh (24 August 2021). "Famine crisis looms in Madagascar after worst drought since 1981". Times Live Zambia. Archived from the original on 24 August 2021. Retrieved 24 August 2021.

- ^ Floch, Fabrice (3 October 2022). "Madagascar : 23 millions de dollars pour lutter contre la famine des enfants" [Madagascar: $23 million to fight child starvation]. réunion.1 (in French). Retrieved 4 October 2022.