Kellogg's

| |

| Formerly | Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company (1906–1909) Kellogg Toasted Corn Flake Company (1909–1922) Kellogg Company (1922–2023) |

|---|---|

| Company type | Public |

| Industry | Food processing |

| Founded | February 19, 1906 (as Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company) in Battle Creek, Michigan, U.S. |

| Founder | Will Keith Kellogg |

| Headquarters | , U.S. |

Area served | Worldwide |

Key people | Steven Cahillane (chairman & CEO) |

| Products |

|

| Brands | |

| Revenue | |

| Total assets | |

| Total equity | |

| Owners |

(Sale to Mars Inc. pending) |

Number of employees | c. 23,000 (2023) |

| Website | kellanova |

| Footnotes / references [1][2] | |

Kellanova, formerly known as the Kellogg Company and commonly known as Kellogg's, is an American multinational food manufacturing company headquartered in Chicago, Illinois, US. Kellanova produces and markets convenience foods and snack foods, including crackers and toaster pastries, cereal, and markets their products by several well-known brands including the Kellogg's brand itself, Rice Krispies Treats, Pringles, Eggo, and Cheez-It. Outside North America, Kellanova markets cereals such as Corn Flakes, Rice Krispies, Frosties and Coco Pops.

Kellogg's products are manufactured and marketed in over 180 countries.[3] Kellanova's largest factory is at Trafford Park in Trafford, Greater Manchester, United Kingdom, which is also the location of its UK headquarters.[4] Other corporate office locations outside of Chicago include Battle Creek, Dublin (European Headquarters), Shanghai, and Querétaro City, Mexico.[5] Kellogg's held a Royal Warrant from Queen Elizabeth II until her death in 2022.[6]

Kellogg's was split into two companies on October 2, 2023, with WK Kellogg Co owning the North American cereal division, and the existing company being rebranded to "Kellanova", owning snack brands such as Pop-Tarts and Pringles alongside the international cereal division. The purpose of the split was to separate the faster-growing convenience food, and international cereal products market, from the slower growth North American cereal market. "Kellogg's" itself became a brand name of both companies.

History

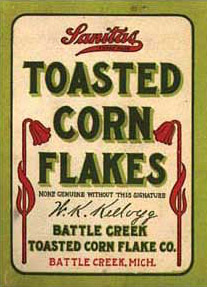

In 1876, John Harvey Kellogg became the superintendent of the Battle Creek Sanitarium (originally the Western Health Reform Institute founded by Ellen White), and his brother, W. K. Kellogg, worked as the bookkeeper. This is where corn flakes were created and led to the eventual formation of the Kellogg Company.

For years, W. K. Kellogg assisted his brother in research to improve the vegetarian diet of the Battle Creek Sanitarium's patients, especially in the search for wheat-based granola. The Kelloggs are best known for the invention of the famous breakfast cereal corn flakes. The development of the flaked cereal in 1894 has been variously described by those involved: Ella Eaton Kellogg, John Harvey Kellogg, his younger brother Will Keith Kellogg, and other family members. There is considerable disagreement over who was involved in the discovery and the roles that they played.[7] It is generally agreed that, upon being called out one night, John Kellogg left a batch of wheat-berry dough behind. Rather than throwing it out the following day, he sent it through the rollers and was surprised to obtain delicate flakes, which could then be baked.[7]

W. K. Kellogg persuaded his brother to serve the food in a flake form. Soon the flaked wheat was being packaged to meet hundreds of guest mail-order requests after they left the Sanitarium. However, John forbade his brother Will to distribute the cereal beyond his own consumers. As a result, the brothers fell out, and W. K. launched the Battle Creek Toasted Corn Flake Company on February 19, 1906.[8][9] On July 4, 1907, a fire destroyed the main factory building. W. K. Kellogg had the new plant in full operation six months after the fire.[10]

Convincing his brother to relinquish rights to the product, Will's company produced and marketed the hugely successful Kellogg's Toasted Corn Flakes and was renamed to the Kellogg Toasted Corn Flake Company in 1909 and to the Kellogg Company in 1922.[8] By 1909, Will's company produced 120,000 cases of Corn Flakes daily. John, who resented his brother's success, filed suit against Will's company in 1906 for the right to use the family name. The resulting legal battle, which included a trial that lasted an entire month, ended in December 1920 when the Michigan Supreme Court ruled in Will's favor.[11]

In 1931, the Kellogg Company announced that most of its factories would shift towards 30-hour work weeks from the usual 40. W. K. Kellogg stated that he did this so that an additional shift of workers would be employed to support people through the depression era. This practice remained until World War II and continued briefly after the war, although some departments and factories remained locked into 30-hour work weeks until 1980.[12]

In 1964, Kellogg's introduced its first non-cereal product: a pastry which can be heated in a toaster, called Pop-Tarts.[13] From 1969 to 1970, the slogan “Kellogg's puts more into your day” was used on Sunday morning TV shows. From 1969 to 1977, Kellogg's acquired various small businesses, including Salada Tea, Fearn International, Mrs. Smith's Pies, Eggo, and Pure Packed Foods;[14] however, it was later criticized for not diversifying further, as General Mills and Quaker Oats had. After underspending its competition in marketing and product development, Kellogg's US market share hit a low of 36.7% in 1983. A prominent Wall Street analyst[who?] called it "a fine company that's past its prime" and the cereal market was being regarded as "mature". Such comments stimulated Kellogg chairman William E. LaMothe to improve, which primarily involved approaching the demographic of 80 million baby boomers rather than marketing children-oriented cereals. In emphasizing cereal's convenience and nutritional value, Kellogg's helped persuade U.S. consumers aged 25 to 49 to eat 26% more cereal than people of that age ate five years prior. The U.S. ready-to-eat cereal market, worth $3.7 billion at retail in 1983, totaled $5.4 billion by 1988 and had expanded three times as fast as the average grocery category. Kellogg's also introduced new products, including Crispix, Raisin Squares, and Nutri-Grain Biscuits, and reached out internationally with Just Right aimed at Australians and Genmai Flakes for Japan. During this time, the company maintained success over its top competitors, General Mills, which largely marketed children's cereals, and Post, which had difficulty in the adult cereal market.[15]

21st century

In 2001, Kellogg's acquired the Keebler Company for $3.87 billion.[16] Over the years, it has also gone on to acquire Morningstar Farms and Kashi divisions or subsidiaries. Kellogg's also owns the Bear Naked, Natural Touch, Cheez-It, Murray, Austin cookies and crackers, Famous Amos, Gardenburger (acquired 2007), and Plantation brands. Presently, Kellogg's is a member of the World Cocoa Foundation.[17]

In 2012, Kellogg's became the world's second-largest snack food company (after PepsiCo) by acquiring the potato chip brand Pringles from Procter & Gamble for $2.7 billion in a cash deal.[18]

In 2017, Kellogg's acquired Chicago-based food company Rxbar for $654 million.[19] Earlier that year, Kellogg's also opened new corporate office space in Chicago's Merchandise Mart for its global growth and IT departments.[20] In the UK, Kellogg's also released the W. K. Kellogg brand of organic, vegan and plant-based cereals (such as granolas, organic wholegrain wheat, and "super grains") with no added sugars.[21]

In 2018, Kellogg's decided to cease their operations in Venezuela due to the economic crisis in the country.[22] Their factories were taken by the Venezuelan state under the Nicolás Maduro administration. In mid-2019, Venezuelan Kellogg's cereal boxes began portraying the Venezuelan flag and a motto from Maduro: "Together, everything is possible" (Spanish: Juntos todo es posible) alongside Kellogg's logo and mascots were sold all over the country. Kellogg's considers it as an illicit use, and the company stated they would take legal action.[23]

On April 1, 2019, it was announced that Kellogg's was selling Famous Amos, Murray's, Keebler, Mother's, and Little Brownie Bakers (one of the producers of the cookies for the Girl Scouts of the USA) to Ferrero SpA for $1.4 billion.[24][25][26] On July 29, 2019, that sale was completed.[27] Kellogg's kept the Keebler cracker line and replaced the Keebler name on their crackers with the Kellogg's name.

In June 2019, Kellogg's announced their next-generation Kellogg's® Better Days global commitment, focusing on hunger, children, and farmers, with specific targets to reach by 2030.[28]

In October 2019, Kellogg's partnered with GLAAD by "launching a new limited edition "All Together Cereal" and donating $50,000 to support GLAAD's anti-bullying and LGBTQ advocacy efforts". The All Together cereal combined six mini cereal boxes into one package to bring attention to anti-bullying.[29]

In January 2020, Kellogg's decided to work with suppliers to phase out the use of glyphosate by 2025, which some farmers have used as a drying agent for wheat and oats supplied to Kellogg's.[30]

In October 2021, workers at all of Kellogg's cereal-producing plants in the United States went on a strike conducted by the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers' International Union over disagreements over the terms of a new labor contract.[31] On December 3, 2021, a tentative deal was struck to end the worker strike,[32] but the union members overwhelmingly rejected the tentative agreement[33] and Kellogg's management announced they would seek to replace all 1,400 striking workers.[34] On December 21, 2021, about 1,400 Kellogg workers approved a collective bargaining agreement, ending the strike, which had lasted 77 days.[35][36][37]

On June 21, 2022, Kellogg's announced that the company would spin off three cereal, snacks, and plant-based food divisions.[38][39] The North American cereal and plant-based food spin-off companies will keep Battle Creek as their headquarters and the new snack and international cereal company will be based in Chicago.[40] The successor company, known as Global Snacking Co. temporarily, represents 80 percent or $11.4 billion of Kellogg's sales. 60 percent of Global Snacking's business was snacks, and nearly half of the company's business was in the United States. The cereal business, temporarily called North America Cereal Co., would be the second-largest American cereal company and the largest in Canada and the Caribbean, with 5 of the top 11 brands and $2.4 billion in annual sales. Plant-based foods, representing $340 million in annual sales, would be called "Plant Co." and could even be sold.[41]

In January 2023, Kellogg's shelved its plans to spin off its plant food business and would retain it as part of Global Snacking Co.[42] On March 15, 2023, Kellogg's announced that North America Cereal Co. branch will be named WK Kellogg Co and Global Snacking Co. branch will be called Kellanova. The split was structured with Kellanova as the surviving company, using the ticker symbol "K" on the NYSE.[43] The WK Kellogg Co took the NYSE stock symbol "KLG".[44] The split was completed on October 2, 2023.[45][46]

On August 14, 2024, it was announced that Mars Inc., the owner of M&M's and Snickers, agreed to purchase Kellanova for nearly $30 billion. The deal is expected to close in the first half of 2025.[47]

Finances

For the fiscal year 2017, Kellogg's reported earnings of US$1.269 billion, with an annual revenue of US$12.932 billion, a decline of 0.7% over the previous fiscal cycle. Kellogg's market capitalization was valued at over US$22.1 billion in November 2018.[48]

| Year | Revenue in mil. US$ |

Net income in mil. US$ |

Total Assets in mil. US$ |

Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 10,177 | 980 | 10,575 | [49] |

| 2006 | 10,907 | 1,004 | 10,714 | [49] |

| 2007 | 11,776 | 1,103 | 11,397 | [49] |

| 2008 | 12,822 | 1,148 | 10,946 | [49] |

| 2009 | 12,575 | 1,212 | 11,200 | [49] |

| 2010 | 12,397 | 1,287 | 11,847 | [50] |

| 2011 | 13,198 | 866 | 11,943 | [51] |

| 2012 | 14,197 | 961 | 15,169 | [52] |

| 2013 | 14,792 | 1,807 | 15,474 | [53] |

| 2014 | 14,580 | 632 | 15,153 | [54] |

| 2015 | 13,525 | 614 | 15,251 | [55] |

| 2016 | 13,014 | 694 | 15,111 | [56] |

| 2017 | 12,923 | 1,269 | 16,351 | [57] |

| 2018 | 13,547 | 1,336 | 17,780 | [58] |

| 2019 | 13,578 | 960 | 17,564 | [59] |

| 2020 | 13,770 | 1,251 | 17,996 | [60] |

| 2021 | 14,181 | 1,488 | 18,178 | [61] |

Brands

- Bear Naked, Inc.

- Cheez-It Crackers

- Eggo

- Fruit Winders

- Fruity Snacks

- Morningstar Farms

- Club Crackers

- Nutri-Grain

- Pop-Tarts

- Pringles

- Rxbar

- Sunshine Biscuits

- Town House

- Zesta Crackers

- Carr's (US only)

- Rice Krispies Treats

- Incogmeato

- Joybol

- Austin Sandwich Cookies

- Cracklin' Oat Bran

- Gardenburger

- Frozen Breakfast

- Mueslix Cereal

- Pure Organic Fruit Bars

- Toasteds Crackers

- Special K (snack bars)

Cereal

Here is a list of Kellanova's cereals (international only) with available varieties:

- All-Bran: All-Bran Original, All-Bran Bran Buds, All-Bran Bran Flakes (UK), All-Bran Extra Fiber, All-Bran Guardian (Canada)

- Apple Jacks

- Apple Jacks Apple vs Cinnamon Limited Edition

- Apple Jacks 72 Flavor Blast (Germany)

- Bran Buds (New Zealand)

- Bran Flakes

- Chocos (India, Europe)

- Chocolate Corn Flakes: a chocolate version of Corn Flakes. First sold in the UK in 1998 (as Choco Corn Flakes or Choco Flakes), but discontinued a few years later. Re-released in 2011.

- Cinnabon

- Cinnamon Mini Buns

- Coco Pops Coco Rocks

- Coco Pops Special Edition Challenger Spaceship

- Coco Pops Crunchers

- Coco Pops Mega Munchers

- Coco Pops Moons and Stars

- Cocoa Krispies or Coco Pops (also called Choco Pops in France, Choco Krispies in Portugal, Spain, Germany, Austria, and Switzerland, Choco Krispis in Latin America)

- Cocoa Flakes

- Corn Flakes

- Complete Wheat Bran Flakes/Bran Flakes

- Corn Pops

- Country Store

- Cracklin' Oat Bran

- Crayola Jazzberry Cereal: In 2021, Kellogg and Crayola teamed up to create a fruit flavored cereal with a coloring book on the box.[62]

- Crispix

- Crunch: Caramel Nut Crunch, Cran-Vanilla Crunch, Toasted Honey Crunch

- Crunchy Nut (formerly Crunchy Nut Cornflakes)

- Crunch Nut Bran

- Cruncheroos

- Disney cereals: Disney Hunny B's Honey-Graham, Disney Mickey's Magix, Disney Mud & Bugs, Pirates of the Caribbean, Disney Princess

- Donut Shop

- Eggo

- Extra (Muesli): Fruit and Nut, Fruit Magic, Nut Delight

- Froot Loops: Froot Loops, Froot Loops 1⁄3 Less Sugar, Marshmallow Froot Loops, Froot Bloopers

- Frosted Flakes (Frosties outside of the US/Canada): Kellogg's Frosted Flakes, Kellogg's Frosted Flakes 1⁄3Kellogg's Banana Frosted Flakes, Kellogg's Birthday Confetti Frosted Flakes, Kellogg's Cocoa Frosted Flakes, Less Sugar, Tony's Cinnamon Krunchers, Honey Nut

- Frosted Mini-Wheats (known in the UK as Toppas until the early 1990s, when the name was changed to Frosted Wheats. The name Toppas is still applied to this product in other parts of Europe, as in Germany and Austria)

- Fruit Harvest: Fruit Harvest Apple Cinnamon, Fruit Harvest Peach Strawberry, Fruit Harvest Strawberry Blueberry

- Fruit 'n Fibre (not related to the Post cereal of the same name sold in the US)

- Fruit Winders (UK)

- Genmai Flakes (Japan)

- Guardian (Australia, NZ, Canada)

- Happy Inside: Bold Blueberry, Simply Strawberry, Coconut Crunch

- Honey Loops (formerly Honey Nut Loops)

- Honey Nut Corn Flakes

- Honey Smacks (US)/Smacks (other markets)

- Jif Peanut Butter Cereal (US only)

- Just Right: Just Right Original, Just Right Fruit & Nut, Just Right Just Grains, Just Right Tropical, Just Right Berry & Apple, Just Right Crunchy Blends – Cranberry, Almond & Sultana (Australia/NZ), Just Right Crunchy Blends – Apple, Date & Sultana (Australia/NZ)

- Khampa Tsampa- Roasted Barley (Tibet)[63]

- Kombos

- Krave – chocolate cereal introduced in the UK in 2010, then rolled out in Europe as Tresor or Trésor in 2011, and in North America in 2012

- Komplete (Australia)

- Low-Fat Granola: Low-Fat Granola, Low-Fat Granola with Raisins

- Mini Max

- Mini Swirlz

- Mini-Wheats: Mini-Wheats Frosted Original, Mini-Wheats Frosted Bite Size, Mini-Wheats Frosted Maple & Brown Sugar, Mini-Wheats Raisin, Mini-Wheats Strawberry, Mini-Wheats Vanilla Creme, Mini-Wheats Strawberry Delight, Mini-Wheats Blackcurrant

- Mueslix: Mueslix with Raisins, Dates & Almonds

- Nutri-Grain

- Nut Feast

- Oat Bran: Cracklin' Oat Bran

- Optivita

- Pop-Tarts Bites: Frosted Strawberry, Frosted Brown Sugar Cinnamon

- Raisin Bran/Sultana Bran: Raisin Bran, Raisin Bran Crunch, Sultana Bran (Australia/NZ), Sultana Bran Crunch (Australia/NZ)

- Raisin Wheats

- Rice Krispies/Rice Bubbles: Rice Krispies, Frosted Rice Krispies (Ricicles in the UK), Gluten Free Rice Krispies, Rice Bubbles, LCMs, Rice Krispies Cocoa (Canada only), Rice Crispies Multi-Grain Shapes, Rice Krispies Treats Cereal[64]

- Rocky Mountain Chocolate Factory Chocolatey Almond cereal

- Scooby-Doo cereal: Cinnamon Marshmallow Scooby-Doo! Cereal

- Smart Start: Smart Start, Smart Start Soy Protein Cereal

- Smorz

- Special K: Special K, Special K low carb lifestyle, Special K Red Berries, Special K Vanilla Almond, Special K Honey & Almond (Australia), Special K Forest Berries (Australia), Special K Purple Berries (UK), Special K Light Muesli Mixed Berries & Apple (Australia/NZ), Special K Light Muesli Peach & Mango flavour (Australia/NZ), Special K Dark Chocolate (Belgium), Special K Milk Chocolate (Belgium), Special K Sustain (UK)

- Spider-Man cereal: Spider-Man Spidey-Berry

- SpongeBob SquarePants cereal

- Strawberry Pops (South Africa)

- Super Mario Cereal

- Sustain: Sustain, Sustain Selection

- Tresor (Europe)

- Variety

- Vector (Canada only)

- Yeast bites with honey

- Kringelz (formerly known as ZimZ!): mini cinnamon-flavored spirals. Only sold in Germany and Austria[65][66]

Discontinued cereals and foods

This section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2015) |

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (February 2024) |

- Banana Bubbles[67]

- Banana-flavoured variation of Rice Krispies. First appeared in the UK in 1995, but discontinued shortly thereafter.

- Banana Frosted Flakes[68]

- Bart Simpson's No Problem-O's and Bart Simpson's Eat My Shorts[69][70]

- Sold in the UK for a limited period

- Bart Simpson Peanut Butter Chocolate Crunch Cereal[71]

- Bigg Mixx cereal[71]

- Buckwheat & Maple[72]

- Buzz Blasts (based on Buzz Lightyear from the Toy Story movies)[71]

- C-3PO's cereal: Introduced in 1984 and inspired by the multi-lingual droid from Star Wars, the cereal called itself "a New (crunchy) Force at Breakfast" and was composed of "twin rings phased together for two crunches in every double-O". In other words, they were shaped like the digit 8. After severing the cereal's ties to Star Wars, the company renamed it Pro-Grain and promoted it with sports-oriented commercials.[73]

- Cinnamon Crunch Crispix

- Cinnamon Mini-Buns

- Cocoa Hoots: Manufactured briefly in the early 1970s, this cereal resembled Cheerios but was chocolate-flavored. The mascot was a cartoon character named Newton the Owl, and one of its commercials featured a young Jodie Foster.

- Coco Pops Strawss

- Complete Oat Bran Flakes

- Concentrate[74]

- Corn Flakes with Instant Bananas

- Corn Soya cereal

- Crunchy Loggs[71]

- Double Dip Crunch[64]

- Eggo Waf-Fulls

- Frosted Krispies

- Frosted Rice: This was a combination of Frosted Flakes and Rice Krispies, using Rice Krispies with frosting on them. Tony Jr. was the brand's mascot.

- Fruit Twistables

- Fruity Marshmallow Krispies

- Golden Crackles

- Golden Oatmeal Crunch (later revised to Golden Crunch)

- Gro-Pup Dog Food and Dog Biscuits

- Heartwise (which contained psyllium, an Indian-grown grain used as a laxative and cholesterol-reducer)[75]

- Homer's Cinnamon Donut Cereal (based on The Simpsons TV cartoon)[71]

- Kenmei Rice Bran cereal[76]

- KOMBOs (orange, strawberry and chocolate flavors)[71][77]

- Kream Krunch

- Krumbles cereal:[78] Manufactured from approximately the 1920s to the mid-1960s; based on shreds of wheat but different from shredded wheat in texture. Unlike the latter, it tended to remain crisp in milk. In the Chicago area, Krumbles was available into the late 1960s. It was also high in fiber, although that attribute was not in vogue at the time.

- Marshmallow Krispies (later revised to Fruity Marshmallow Krispies)[64]

- Most

- Mr. T's Muscle Crunch (1983–1985)

- Nut & Honey Crunch[71]

- OJ's ("All the Vitamin C of a 4-oz. Glass of Orange Juice")[79]

- OKs cereal (early 1960s): Oat-based cereal physically resembling the competing brand Cheerios, with half the OKs shaped like letter O's and the other half shaped like K's, but did not taste like Cheerios. OKs originally featured Big Otis, a giant, burly Scotsman, on the box; this was replaced by the more familiar Yogi Bear.

- Pep: Best remembered as the sponsor of the Superman radio serial.

- Pokémon Cereal: A limited edition cereal that promoted the Pokémon franchise. It consisted of O-shaped cereal and marshmallows shaped liked Pikachu, Oddish, Poliwhirl and Ditto. They later returned during Gen II with marshmallows formed like Cleffa, Wobbuffet and Pichu for a short time.

- Pop-Tarts Crunch[64]

- Powerpuff Girls Cereal

- Product 19: Discontinued in 2016

- Pro Grain[80]

- Puffa Puffa Rice (late 1960s–early 1970s)

- Raisin Squares[81]

- Raisins Rice and Rye[82]

- Razzle Dazzle Rice Krispies

- Ricicles

- Sugar Stars/Stars/All-Stars cereal

- Strawberry Rice Krispies

- Strawberry Splitz

- 3 Point Pops[83]

- Tony's Cinnamon Krunchers[71]

- Tony's Turboz

- Triple Snack[77]

- Yogos: Discontinued in 2011

- Yogos (Berry, Mango, Strawberry, 72 Flavor Blast (Germany), Cookies and Cream, Tacos (Mexico))

- Yogos Rollers: Discontinued in 2009

- Zimz: Cinnamon Cereal Discontinued

- Start (UK)

Marketing

Various methods have been used in the company's history to promote the company and its brands. Foremost among these is the design of the Kellogg's logo by Ferris Crane under the art direction of famed type guru Y. Ames. Another was the well-remembered jingle "K E double-L, O double-good, Kellogg's best to you!".[citation needed]

With the rising popularity of patent medicine in early 20th century advertising, The Kellogg Company of Canada published a book named A New Way of Living that showed readers "how to achieve a new way of living; how to preserve vitality; how to maintain enthusiasm and energy; how to get the most out of life because of a physical ability to enjoy it". It touted the All-Bran cereal as the secret to leading "normal" lives free of constipation.[84]

Kellogg's was a major sponsor throughout the run of the hit CBS panel show What's My Line?[85] It and its associated products Frosted Flakes and Rice Krispies were also major sponsors for the PBS Kids children's animated series Dragon Tales.[86]

Kellogg's is a sponsor of USA Gymnastics and produced the Kellogg's Tour of Gymnastics, a 36-city tour held in 2016 after the Olympic games and featured performances by recent medal-winning gymnasts from the United States.[87]

Kellogg's is currently the title sponsor of three college football bowl games. In 2019, Kellogg's became the new title sponsor of the Sun Bowl game, with the game being branded as the "Tony the Tiger Sun Bowl".[88] This was followed in 2020 by the company using its Cheez-It brand to sponsor of the game now known as the Pop-Tarts Bowl.[89] In 2022, Kellogg's added the Citrus Bowl to its bowl sponsorships, with the game branded as the "Cheez-It Citrus Bowl".[90]

Premiums and prizes

W.K. Kellogg was the first to introduce prizes in boxes of cereal. The marketing strategy that he established has produced thousands of different cereal box prizes that have been distributed by the tens of billions.[91]

Children's premiums

Beginning in 1909, Kellogg's Corn Flakes had the first cereal premium with The Funny Jungleland Moving Pictures Book. The book was originally available as a prize that was given to the customer in the store with the purchase of two packages of the cereal.[92] But in 1909, Kellogg's changed the book giveaway to a premium mail-in offer for the cost of a dime. Over 2.5 million copies of the book were distributed in different editions over a period of 23 years.[93]

Cereal box prizes

In 1945, Kellogg's inserted a prize in the form of pin-back buttons into each box of Pep cereal. Pep pins have included U.S. Army squadrons as well as characters from newspaper comics and were available through 1947. There were five series of comic characters and 18 different buttons in each set, with a total of 90 in the collection.[91] Other manufacturers of major brands of cereal, including General Mills, Malt-O-Meal, Nestlé, Post Foods, and Quaker Oats, followed suit and inserted prizes into boxes of cereal to promote sales and brand loyalty.

Mascots

Licensed brands have been omitted since the corresponding mascots would be obvious (for example, Spider-Man is the mascot for Spider-Man Spidey-Berry).

- Cocoa Hoots cereal: Newton the Owl

- Cocoa Krispies cereal (Known as Choco Krispis in Latin America, Choco Krispies in Germany, Austria, Spain, and Switzerland, Chocos in India, and Coco Pops in Australia, the UK, and Europe): Jose (monkey), Coco (monkey), Melvin (elephant), Snagglepuss (Hanna-Barbera character), Ogg (caveman), Tusk (elephant), and Snap, Crackle and Pop (who were also, and remain as of February 2014, the Rice Krispies mascots; see below)

- Corn Flakes cereal: Cornelius (rooster)

- Frosted Flakes (known as Frosties outside the US/Canada, Zucaritas in Latin America and Sucrilhos in Brazil) cereal: Tony the Tiger

- Froot Loops cereal: Toucan Sam

- Honey Smacks (US)/Smacks (other markets) cereal: Dig 'Em Frog

- Raisin Bran cereal: Sunny the Sun

- Rice Krispies (known as Rice Bubbles in Australia and New Zealand) cereal: Snap, Crackle and Pop

- Ricicles (UK Only) cereal: Captain Rik

- Apple Jacks cereal: CinnaMon and Bad Apple

- Honey Loops cereal: Loopy (bumblebee), Pops (honey bee)

- Keebler cookies and crackers: Ernie and the Elves

Motorsports

Kellogg's made its first foray into auto racing between 1991 and 1992 when the company sponsored the #41 Chevrolets fielded by Larry Hedrick Motorsports in the NASCAR Winston Cup Series and driven by Phil Parsons, Dave Marcis, Greg Sacks, Hut Stricklin, and Richard Petty, but they gained greater prominence for their sponsorship of two-time Winston Cup Champion Terry Labonte from 1993 to 2006, the last 12 years of that as the sponsor for Hendrick Motorsports' No.5 car. Kellogg's sponsored the No.5 car for Labonte, Kyle Busch, Casey Mears, and Mark Martin until 2010, and it then served as an associate sponsor for Carl Edwards' #99 car for Roush Fenway Racing.

Kellogg's placed Dale Earnhardt on Kellogg's Corn Flakes boxes for 1993 six-time Winston Cup champion and 1994 seven-time Winston Cup champion, as well as Jeff Gordon on the Mini Wheats box for the 1993 Rookie of the Year, 1995 Brickyard 400 inaugural race, 1997 Champion, and 1998 three-time champion, and a special three-pack racing box set with Dale Earnhardt, Jeff Gordon, Terry Labonte, and Dale Jarrett in 1996.

Merchandising

Kellogg's has used some merchandising for their products. Entertainer Jimmy Durante appeared in some Kellogg's commercials in the 1960s. Kellogg's once released Mission Nutrition, a PC game that came free with special packs of cereal. It played in a similar fashion as Donkey Kong Country; users could play as Tony the Tiger, Coco the Monkey, or Snap, Crackle, and Pop.[citation needed]

Kellogg's has also released "Talking" games. The two current versions are Talking Tony and Talking Sam. In these games, a microphone is used to play games and create voice commands for their computers. In Talking Tony, Tony the Tiger, a famous Kellogg's mascot, would be the main and only character in the game. In Talking Sam, Toucan Sam, would be in the game, instead. Some [toy cars] have the Kellogg's logo on them, and occasionally their mascots. There was also a Talking Snap Crackle and Pop software.[citation needed]

Olympic Games

Kellogg's frequently partners with the Olympic Games to feature American athletes from the Olympic Games on the packages of their cereal brands.[94] In 2017, the company announced its marketing campaign for the 2018 Winter Olympic Games featuring American athletes Nathan Chen, Kelly Clark, Meghan Duggan and Mike Schultz.[95]

Misleading claims

Advertising

We expect more from a great American company than making dubious claims—not once, but twice—that its cereals improve children's health...

—Jon Leibowitz, Chairman of the F.T.C.[96]

On June 3, 2010, Kellogg's was found to be making unsubstantiated and misleading claims in advertising their cereal products by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).[96][97][98]

Kellogg's responded by stating "We stand behind the validity of our product claims and research, so we agreed to an order that covers those claims. We believe that the revisions to the existing consent agreement satisfied any remaining concerns."[98]

The FTC had previously found fault with Kellogg's claims that Frosted Mini-Wheats cereal improved kids' attentiveness by nearly 20%.[99]

The Children's Advertising Review Unit of the Council of Better Business Bureaus has also suggested that the language on Kellogg Pop-Tarts packages saying the pastries are "Made with Real Fruit" should be taken off the products.[100] In July 2012, the UK banned a "Special K" advertisement due to its citing caloric values that did not take into account the caloric value of milk consumed with the cereal.[101] In 2016 an ad telling UK consumers that Special K is “full of goodness” and “nutritious” was banned.[102]

Questionable nutritional value

Some of Kellogg's marketing has been questioned in the press, prompted by an increase in consumer awareness of the mismatch between the marketing messages and the products themselves.[103]

Food bloggers are also questioning the marketing methods used by cereal manufacturing companies such as Kellogg's, due to their high sugar content and use of ingredients such as high-fructose corn syrup.[104]

2021 Pop-Tarts lawsuit

A class-action lawsuit was filed against Kellogg's in October 2021 claiming they are not putting enough strawberries in their strawberry flavored Pop-Tarts, and seeking $5 million in damages.[105] In April 2022, the lawsuit was dismissed by a federal judge.[106]

Another lawsuit was filed against Kellog's in 2021, with the plaintiff claiming that Kellogg's defrauded customers regarding the contents of its Frosted Chocolate Fudge Pop-Tarts. The plaintiff stated she would not have purchased the Pop-Tarts had she known they did not contain milk, milkfat, or butter. In June 2022, a US district judge dismissed the lawsuit, stating that a reasonable consumer would not expect those ingredients.[107]

Recalls

2010 cereal recall

On June 25, the company voluntarily began to recall about 28 million boxes of Apple Jacks, Corn Pops, Froot Loops and Honey Smacks because of an unusual smell and flavor from the packages' liners that could make people ill. Kellogg's said about 20 people complained about the cereals, including five who reported nausea and vomiting. Consumers reported the cereal smelled or tasted waxy or like metal or soap. Company spokeswoman J. Adaire Putnam said some described it as tasting stale. However, no serious health problems had been reported.[108]

The suspected chemical that caused the illnesses was 2-methylnaphthalene, used in the cereal packaging process. Little is known about 2-methylnaphthalene's impact on human health as the Food and Drug Administration has no scientific data on its impact on humans, and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) also does not have health and safety data. This is despite the EPA having sought information on it from the chemical industry for 16 years. 2-Methylnaphthalene is a component of crude oil and is "structurally related to naphthalene, an ingredient in mothballs and toilet-deodorant blocks" that the EPA considers a possible human carcinogen.[109][110]

Kellogg's offered consumers refunds in the meantime.[111] Only products with the letters "KN" following the use-by date were included in the recall.[112] The products were distributed throughout the US and began arriving in stores in late March 2010. Products in Canada were not affected.[113]

2012 cereal recall

Kellogg's issued a voluntary recall of some of its "Frosted Mini-Wheats Bite Size Original" and "Mini-Wheats Unfrosted Bite Size" products due to the possibility of flexible metal mesh fragments in the food. The affected products varied in size from single-serving bowls to large 70-ounce cartons. Use-by dates printed on the recalled packages ranged from April 1, 2013, to September 21, 2013, and were accompanied by the letters KB, AP or FK.[114]

Human rights violations and strikes

Human right violations of palm oil in 2016

According to Amnesty International in 2016, Kellogg's palm oil provider Wilmar International profited from 8 to 14-year-old child labor and forced labor. Some workers were extorted, threatened or not paid for work. Some workers suffered severe injuries from chemicals such as Paraquat.[115][116] Kellogg's alleged not being aware of the child abuses due to traceability; Amnesty's human rights director replied that "Using mealy-mouthed excuses about 'traceability' is a total cop-out."[117]

2021 strike

In October 2021, over a thousand employees at four Kelloggs manufacturing plants in the United States went on strike for better working conditions and higher wages. Two months into the strikes, Kelloggs fired all the striking workers and posted their jobs in December after negotiations with the BCTGM union failed. During the talks, Kelloggs had threatened to move jobs to Mexico if the union did not agree to Kelloggs' proposal.[118] Kelloggs also filed a lawsuit against the union.[119] As a result, several calls for a boycott went viral.[120][121]

Political involvement

Genetically modified foods labelling

Kellogg's donated around US$2 million opposing California Proposition 37, a 2012 ballot initiative that, if enacted, would have required compulsory labeling of genetically engineered food products.[122] In March 2016, though, they vowed to label all of their products with genetically modified organisms as such by 2020.[123]

Climate change

In August 2014, Kellogg's called on the President to support the Paris Agreement on climate change.[124] In 2016, Kellogg Company urged President-elect Donald Trump to "continue the Paris Climate Agreement".[125]

Voter ID laws

Kellogg's has donated to notable groups opposing voter-ID laws, such as the Applied Research Center (now RaceForward).[126] The company also decided to remove their advertisements from the Breitbart News website.[127] Breitbart News in turn called for a boycott of Kellogg's products.[128]

Education grant

In January 2012, Kellogg's gave the Calhoun School a $250,000 grant for a "three-part youth-based project on issues of white privilege and institutionalized racism".[129]

Operations

- Australia:

- Pagewood[131]

- Charmhaven (snack and cereal plant closed in 2014.)[132]

- Belgium: Zaventem & Mechelen plant

- Brazil: São Paulo

- Colombia: Bogotá

- Canada:

- Mississauga, Ontario – Canadian head office

- Anjou, Quebec – Eastern Canada sales office

- Calgary, Alberta – Western Canada sales office

- London, Ontario – manufacturers and distributes cereals (including Corn Flakes) in Canada. Closed at end of 2014,[133]

- Belleville, Ontario – cereal production plant opened 2009 and upgraded 2011; took over some operations from London after 2014

- China: Shanghai – Joint venture with agribusiness and food company Yihai Kerry

- Ecuador: Guayaquil

- France: Noisy-le-Grand, Paris[134]

- Germany: Hamburg (sales and marketing for Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Scandinavia; production in Germany shut down in 2018)[135]

- India: Mumbai

- Republic of Ireland: European Head Office – Kellogg Europe Trading, Swords, Dublin[136]

- Italy: Milan

- Japan: Shinjuku, Tokyo[137]

- Malaysia: Bandar Enstek, Negeri Sembilan[138][139]

- Mexico: Querétaro

- Middle East[140]

- Netherlands: Den Bosch[141][142]

- Philippines: Alaska Milk Corporation[143]

- Poland: Kutno[144]

- Portugal: Lisbon

- Russia: Kellogg Rus LLC[136] (Sold to the Russian company Chernogolovka in July 2023)[145]

- South Africa: Springs[146]

- South Korea: Seoul

- Spain: Valls (cereal production plant) and Alcobendas (Spanish head office)[136]

- Sri Lanka: Colombo; Sri Jayawardenapura Kotte

- Thailand: Bangkok, Rayong (snacks and cereals)

- United Kingdom:

- England: Manchester[136]

- Scotland: Portable Foods Manufacturing Livingston[136]

- Wales: Wrexham including Portable Foods Manufacturing[136]

- United States:

- Morocco

See also

- W. K. Kellogg Foundation

- Kellogg's Cereal City USA – a former tourist attraction in Battle Creek, Michigan focused on the company's history

- List of breakfast cereals

- Toucan Sam#Maya Archaeology Initiative for a 2011 trademark dispute over another organization's toucan logo

- A. D. David Mackay

References

- ^ Kellanova 2023 Annual Report (Form 10-K). SEC.gov (Report). U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. February 20, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Proxy Statement". March 2, 2023. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Kellogg Company Fact Sheet (PDF)" (PDF). filecache.drivetheweb.com. KelloggCompany. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 25, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2014.

- ^ a b "Global brand, local values". Manchester Evening News. May 27, 2008. Archived from the original on July 19, 2012. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ^ "Our Locations". kelloggcareers.com. Archived from the original on May 28, 2018. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ "Kellogg Marketing & Sales Co (UK) Ltd". royalwarrant.org. Royal Warrant Holders Association. Archived from the original on January 28, 2018. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ a b Markel, Howard (2017). The Kelloggs: The Battling Brothers of Battle Creek. Pantheon. pp. 110–112, 129–133. ISBN 978-0307907271. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ a b Shurtleff, William; Aoyagi, Akiko (January 6, 2014). History of Seventh-day Adventist Work with Soyfoods, Vegetarianism, Meat Alternatives, Wheat Gluten, Dietary Fiber and Peanut Butter (1863–2013): Extensively Annotated Bibliography and Sourcebook. Soyinfo Center. pp. 994–95. ISBN 978-1-928914-64-8. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ Benjamin, André (June 30, 2013). Conquer The Recession. Andre J Benjamin. p. 27. GGKEY:6SA764GJCF1. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved August 20, 2018.

- ^ "The Kelloggs: The Battling Brothers of Battle Creek, book review on Adventist Today website". October 18, 2017. Archived from the original on March 14, 2023. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ Kellogg v. Kellogg Toasted Corn Flake Co., 212 Mich. 95. 180 N.W. 397 (1920)

- ^ Kaplan, Jeffrey (May–June 2008). "The Gospel of Consumption". Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved June 25, 2010.

- ^ "1964 : Kellogg's Pop Tarts Unleashed on Cleveland, Instant Hit (2020-09-14)". Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ "Kellogg Company History". FundingUniverse.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2020. Retrieved November 28, 2019.

- ^ Sellers, Patricia (August 29, 1988). "How King Kellogg Beat the Blahs". Fortune. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- ^ "Kellogg Plans to Cut 470 Jobs As Part of Keebler Acquisition". The Wall Street Journal. March 30, 2001. Archived from the original on December 31, 2019. Retrieved September 11, 2019.

- ^ "What are you doing about sustainable cocoa?". Kelloggs. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ "Kellogg to buy Pringles for $2.7 billion". Reuters.com. February 15, 2012. Archived from the original on August 26, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ Wilkins, Peter. "What $600M RXBar Acquisition By Kellogg's Says About Chicago's Simple Food And Beverage Industry". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 15, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ Ori, Ryan; Trotter, Greg (April 3, 2017). "Kellogg opens 50-employee Merchandise Mart office". chicagotribune.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "Kellogg targets health-conscious consumers with W.K.Kellogg line". Foodbev.com. Foodbev Media. November 14, 2017. Archived from the original on August 24, 2018. Retrieved August 23, 2018.

- ^ "Kellogg Says It's Discontinuing Venezuela Operations". Bloomberg. Retrieved May 17, 2018.[dead link]

- ^ Olmo, Guillermo D. (November 15, 2019). "Kellogg's: cómo los cereales más famosos del mundo se volvieron chavistas en Venezuela" [Kellogg's in Venezuela: how the world's most famous cereals became Chavez-ian]. BBC.com (in Spanish). Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved December 9, 2019.

- ^ Hirsch, Lauren (April 1, 2019). "Kellogg to sell Keebler, Famous Amos to Nutella-owner Ferrero". CNBC.com. Archived from the original on January 28, 2021. Retrieved April 6, 2019.

- ^ Reddy, Arjun. "Kellogg has agreed to sell its Keebler and Famous Amos businesses to Ferrero for $1.3 billion". Business Insider. Archived from the original on August 12, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ Yu, Douglas. "Ferrero Enters U.S. Snack Aisle With $1.3 Billion Acquisition Of Kellogg's Brands". Forbes. Archived from the original on November 7, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ Schultz, Clark (July 29, 2019). "Kellogg closes on Keebler sale". Seeking Alpha. Archived from the original on December 22, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2019.

- ^ "Kellogg Company unveils ambitious next-generation Kellogg's® Better Days global commitment to address food security; driving positive change for people, communities and the planet by the end of 2030". prnewswire.com (Press release). Kellogg Company. Archived from the original on July 12, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ "Kellogg Company Partners With GLAAD For Spirit Day, Launching New 2019 Edition of 'All Together' Cereal". prnewswire.com (Press release). Kellogg Company. Archived from the original on July 11, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2020.

- ^ "Kellogg's pledges to reduce glyphosate, active ingredient in Roundup, in its supply chain". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 14, 2020. Retrieved July 11, 2020 – via webcache.googleusercontent.com.

- ^ Funk, Josh (October 5, 2021). "Workers at all of Kellogg's U.S. cereal plants go on strike". AP News. With contributions from Dee-Ann Durbin. Associated Press. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved October 6, 2021.

- ^ Hernandez, Joe (December 2, 2021). "Kellogg and its cereal workers union reach a tentative deal to end 2-month strike". NPR. Archived from the original on December 4, 2021. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- ^ Bandur, Michelle (December 7, 2021). "No Deal: Union says it has rejected latest offer from Kellogg's". KETV. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ "Kellogg to replace 1,400 strikers as deal is rejected". The Guardian. December 7, 2021. Archived from the original on December 12, 2021. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ Scheiber, Noam (December 21, 2021). "Kellogg workers ratify a revised contract after being on strike since October". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on December 24, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ "Kellogg's Strike Ends: BCTGM Members Ratify New Contract". BCTGM | The Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union. December 21, 2021. Archived from the original on December 24, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ "Kellogg Company Reaches New Tentative Agreement with Union". Kellogg. December 16, 2021. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021.

- ^ Ott, Matt (June 21, 2022). "Kellogg to split into 3; snacks, cereals, plant-based food". Associated Press. Archived from the original on June 21, 2022. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg Company Announces Separation of Two Businesses as Bold Next Steps in Portfolio Transformation" (Press release). Kellogg Company. June 21, 2022. Archived from the original on July 12, 2022. Retrieved March 27, 2023 – via PR Newswire.

- ^ Miller, Kevin (June 21, 2022). "Kellogg Will Split Into Three Companies to Promote Growth". Bloomberg.com. Archived from the original on March 12, 2023. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ^ Springer, Jon (June 27, 2022). "Kellogg bets on snacking—what the breakup means for brands: The food giant will spin off breakfast cereal and plant-based units". Ad Age. Vol. 93, no. 10. p. 1.

- ^ Bedi, Mehr (February 9, 2023). "Kellogg's sales and profit beat estimates, to retain plant-based meat business". Reuters. Archived from the original on February 18, 2023. Retrieved February 18, 2023.

- ^ Valinsky, Jordan (March 15, 2023). "Cheez-It and Pringles company gets a new name". CNN.com. Archived from the original on March 15, 2023. Retrieved March 15, 2023.

- ^ Lucas, Amelia (October 2, 2023). "Kellogg's cereal business begins trading as stand-alone company WK Kellogg". CNBC. Retrieved November 24, 2023.

- ^ Oguh, Chibuike; Vanaik, Granth (October 2, 2023). "Kellanova, WK Kellogg shares slump on first day after spinoff". Reuters.

- ^ "Kellogg Company Board of Directors Approves Separtion into Two Companies, Kellanova and WK Kellogg Co". prnewswire.com (Press release). Kellogg Company. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ Durbin, Dee-Ann; Chapman, Michelle (August 14, 2024). "Sweet and salty deal worth $30 billion would put M&M's and Snickers alongside Cheez-Its and Pringles". Associated Press. Retrieved August 14, 2024.

- ^ "Kellogg Company". annualreports.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved December 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e "Kellanova Co Revenue 1994–2024". Stock Analysis. Retrieved May 13, 2024.

- ^ "Kellogg Revenue 2010–2022 | K". macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg Revenue 2010–2022 | K". macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg Revenue 2010–2022 | K". macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg Revenue 2010–2022 | K". macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg Revenue 2010–2022 | K". macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg Revenue 2010–2022 | K". macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg Revenue 2010–2022 | K". macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg Revenue 2010–2022 | K". macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg Revenue 2010–2022 | K". macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg Revenue 2010–2022 | K". macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg Revenue 2010–2022 | K". macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg Revenue 2010–2022 | K". macrotrends.net. Archived from the original on April 4, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ Fitzpatrick, Caitlyn (December 20, 2020). "Kellogg's is Releasing a Crayola Cereal with a Box That Doubles as a Coloring Book". BestProducts.com. Hearst Magazine Media, Inc. Archived from the original on January 18, 2021. Retrieved February 1, 2021.

- ^ Knaus, John Kenneth (1999). Orphans of the Cold War: America and the Tibetan Struggle for Survival (1st ed.). New York: PublicAffairs. p. 280. ISBN 9781891620850. Retrieved September 16, 2020.

They were supplied with a special version of their staple diet of barley (tsampa) enriched with vitamins and nutrient supplements. This cereal had been developed with the help of the Kellogg Company by the CIA Tibetan Task Force's team doctor, Edward 'Manny' Gunn, who had taken on the problem of finding a ration that would provide the energy the guerrillas needed to operate in these extremes of altitude and temperature. By 1963, loads of 'Khampa tsampa ' were being shipped to the Roof of the World.

- ^ a b c d "Comedy News, Viral Videos, Late Night TV, Political Humor, Funny Slideshows". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on March 2, 2012.

- ^ "Kringelz – Produkte". Kelloggs.de. July 6, 2011. Archived from the original on July 6, 2011.

- ^ "Kringelz – Produkte". Kelloggs.at. July 19, 2011. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011.

- ^ Week, Marketing (November 22, 1996). "Kellogg to axe weakest brands". Marketing Week. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ "Discontinued Cereals List – Kellogg's, Post, General Mills, Nabisco, Ralston, Quaker Cereal". Discontinued Favorites. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ "Kellogg's Bart Simpson's No Problemo's Cereal UK 2002 Advert". Youtube. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ "What's In The Box? – 2003 Kelloggs Bart Simpsons Eat My Shorts Cereal". Youtube. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "A Tribute to Discontinued Cereals". Gunaxin Grub. March 5, 2009. Archived from the original on August 23, 2018. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ "[Kellogg advertisement]". The Ottawa Journal. March 8, 1975. Archived from the original on January 16, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "1984 – Kellogg's – Canada – C-3PO Cereal Cards". StarWarsCards.net. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ "Concentrate Cereal". MrBreakfast.com. Archived from the original on December 3, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ "Heartwise (Kellogg's): Heartwise Cereal Box". MrBreakfast.com. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ "26 Cereals From The '90s You'll Never Be Able To Eat Again". BuzzFeed.com. May 4, 2013. Archived from the original on April 23, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ a b "Breakfast cereal mascots: Beloved and bizarre". cbsnews.com. April 7, 2013. Archived from the original on October 31, 2020. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ "Krumbles Cereal". MrBreakfast.com. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ "Chiller – Scary Good". fearnet.com. Archived from the original on July 25, 2014. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ "PRO GRAIN". MrBreakfast.com. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ "Raisin Squares Cereal". MrBreakfast.com. Archived from the original on December 12, 2020. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ "Raisins Rice & Rye Cereal". MrBreakfast.com. Archived from the original on April 12, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ "3 Point Pops Cereal". MrBreakfast.com. Archived from the original on April 14, 2021. Retrieved March 30, 2014.

- ^ A New Way of Living. Kellogg Company of Canada. 1932. p. 2. Archived from the original on October 20, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2018.

- ^ Robbins, David (April 29, 2014). "What's My Line?: A Treasure Trove". Archived from the original on December 22, 2014. Retrieved December 25, 2014.

- ^ "CTW – Dragon Tales – Fun & Games!". CTW.org. Children's Television Workshop. Archived from the original on June 20, 2000. Retrieved December 5, 2014.

- ^ "Kellogg's Tour of Gymnastics Champions". Kelloggstour.com. Archived from the original on September 30, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ Bedoya, Aaron A.; Bloomquist, Bret. "It's official: The Sun Bowl grabs 'Tony the Tiger' as a sponsor". El Paso Times. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved September 4, 2019.

- ^ "Cheez-It® Heads To Orlando To Join Florida Citrus Sports Beginning With 2020 Season" (Press release). Cheez-It Bowl. May 27, 2020. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- ^ "Cheez-It® Joins Citrus Bowl As Title Partner for the Newly Named Cheez-It® Citrus Bowl" (Press release). Disney Media & Entertainment Distribution. November 15, 2022. Archived from the original on December 8, 2022. Retrieved February 26, 2023.

- ^ a b Taylor, Rod (September 1, 2003). "Kelloggs history, William Keith (W. K.) Kellogg legacy | Promotional Marketing content from Chief Marketer". Promomagazine.com. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ Ament, Phil. "Corn Flakes History – Invention of Kellogg's Corn Flakes". Ideafinder.com. Archived from the original on December 17, 2010. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- ^ "Kellogg's Offers First Cereal Premium Prize". Timelines.com. Archived from the original on April 7, 2013. Retrieved December 27, 2010.

- ^ "Simone Biles and the Final Five Land a Cereal Box—And It's Not Wheaties". Time. Archived from the original on February 27, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ "Kellogg's Olympic Push Begins Well Before the Winter Games". Ad Age. Archived from the original on December 28, 2017. Retrieved January 28, 2018.

- ^ a b "FTC Investigation of Ad Claims that Rice Krispies Benefits Children's Immunity Leads to Stronger Order Against Kellogg". FTC. June 3, 2010. Archived from the original on June 5, 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ^ "In the Matter of Kellogg Company, FTC Docket No. C-4262" (PDF). Concurring Statement of Commissioner Julie Brill and Chairman Jon Leibowitz. Federal Trade Commission. June 3, 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ^ a b Chan, Sewell (June 4, 2010). "Kellogg to Restrict Ads to Settle U.S. Inquiry Into Health Claims for Cereal". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 5, 2010. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ^ Carey, Susan (June 4, 2010). "Snap, Crackle, Slap: FTC Objects to Kellogg's Rice Krispies Health Claim". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on September 12, 2017.

- ^ "Feds say Kellogg ads mislead parents". Top Stocks. MSN Money. June 4, 2010. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved June 4, 2010.

- ^ "Britain bans Kellogg's for 'misleading' advertisement". The Times Of India. July 5, 2012. Archived from the original on July 5, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ^ Sweney, Mark (July 20, 2016). "Kellogg's Special K ads banned over 'full of goodness' and 'nutritious' claims". The Guardian. Archived from the original on May 18, 2017. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- ^ "Parents fed up with junk food ads". The Age. November 9, 2011. Archived from the original on November 11, 2011.

- ^ Enion, Richard (November 16, 2011). "Do Kellogg's Really Care About You?". richeats.tv. Archived from the original on December 27, 2019.

- ^ Geske, Dawn (October 25, 2021). "Kellogg's Sued Over Amount Of Strawberries In Pop-Tarts". International Business Times. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved October 25, 2021.

- ^ Shivaram, Deepa (April 1, 2022). "A federal judge dismisses a lawsuit that claimed Pop-Tarts aren't strawberry enough". NPR. Archived from the original on June 13, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2022.

- ^ Stempel, Jonathan (June 3, 2022). "Kellogg's defeats lawsuit over Chocolate Fudge Pop-Tarts". Reuters. Archived from the original on June 14, 2022. Retrieved June 14, 2022.

- ^ "Kellogg's recalls 28 million boxes of cereal". Allvoices.com. Archived from the original on October 10, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ Layton, Lyndsey (August 2, 2010). "US regulators lack data on health risks of most chemicals". Washington Post. Archived from the original on February 24, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2017.

- ^ "2-Methylnaphthalene (CASRN 91-57-6)". EPA.gov. United States Environmental Protection Agency. May 3, 2007. Archived from the original on September 6, 2010. Retrieved October 27, 2010.

- ^ Hunter, Aina (June 29, 2010). "Kellogg's Cereal Recall: Full List (Apple Jacks, Corn Pops, Froot Loops, Honey Smacks)". cbsnews.com. ViacomCBS. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ Flynn, Dan (June 26, 2010). "Kellogg's Recalls 28 Million Boxes of Cereal". Food Safety News. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ "Kelloggs Recall – Cereal – 2010". The Mary Sue. June 25, 2010. Archived from the original on October 3, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2021.

- ^ Tomson, Bill; Ziobro, Paul. "Kellogg Recalls Mini-Wheats". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on June 23, 2015. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ^ "The Great Palm Oil Scandal: Labour Abuses Behind Big Brand Names". amnesty.org. Amnesty International. November 30, 2016. Archived from the original on April 23, 2018.

- ^ Kishore, Divya (November 30, 2016). "Amnesty report slams popular brands for profiting from labour abuses at Wilmar". Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ Davies, Rob (November 30, 2016). "Firms such as Kellogg's, Unilever and Nestlé 'use child-labour palm oil'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on December 2, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ "'Death of 1,000 cuts': Kellogg's workers on why they're striking". the Guardian. October 7, 2021. Archived from the original on October 7, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ Duffy, Kate. "Kellogg said it's permanently replacing around 1,400 striking factory workers". Business Insider. Archived from the original on December 9, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ dakp15 (December 8, 2021). "A guide to boycotting Kellogg's". r/coolguides. Archived from the original on December 9, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ BloominFunions (December 9, 2021). "Apply now! Kellogg is hiring scabs online. Let's drown their union busting. Mods please sticky!". r/antiwork. Archived from the original on December 9, 2021. Retrieved December 9, 2021.

- ^ "Prop. 37: Requires labeling of food products made from genetically modified organisms. | Voter's Edge". Votersedge.org. November 6, 2012. Archived from the original on November 8, 2012. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ "Kellogg to Label All GMOs Nationwide". The Daily Meal. Archived from the original on June 14, 2018. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ "Kellogg Steps Up to Tackle Climate Change". Oxfam.ca. August 13, 2014. Archived from the original on November 30, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ Davis, Dillion (November 17, 2016). "Kellogg Co. urges Trump to uphold Paris Agreement". The Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved December 2, 2016.

- ^ "Race Forward WK Kellogg Foundation Grant Page". November 30, 2016. Archived from the original on December 20, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ O'Connor, Lydia (November 29, 2016). "Kellogg Is Latest Company To Pull Advertising From Breitbart". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on December 3, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ "Kellogg's dumps Breitbart ads, citing 'values'; Breitbart encourages boycott". Columbus Dispatch. AP. December 1, 2016. Archived from the original on December 2, 2016. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ CRC Staff (May 1, 2013). "The W.K. Kellogg Foundation: Subverting democracy and balkanizing America". Capital Research Center. Archived from the original on December 1, 2016. Retrieved December 3, 2016.

- ^ "Factory". Kellogg's. Archived from the original on August 31, 2011. Retrieved August 3, 2011.

- ^ "Welcome to Careers at Kellogg Australia". Kellogg (Aust.) Pty. Ltd. Archived from the original on October 1, 2011. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- ^ "Kellogg to close London cereal factory next year". CBC News. December 11, 2013. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "Kellogg's to close London plant by the end of 2014". CTVNews.ca. December 10, 2013. Archived from the original on March 27, 2023. Retrieved March 1, 2021.

- ^ "Nous contacter". kelloggs.fr. Archived from the original on May 6, 2014. Retrieved May 6, 2014.

- ^ Beneke, Maren (October 10, 2016). "Bremer Kellogg-Werk wird geschlossen". Weser-Kurier, Bremen. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Kellogg Europe Trading Ltd (KETL)". Kellogg Company. Archived from the original on August 31, 2011. Retrieved August 25, 2011.

- ^ "いい朝食がいい日をつくる – 日本ケロッグ" [Make a good day with a good breakfast – Kellogg Japan]. kellogg.co.jp (in Japanese). Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ^ "Kellogg to invest $130M in Malaysia plant, eyes Asia-Pacific expansion". Venture Capital Post. January 10, 2014. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ "Kellogg Company to invest US$130m in Malaysia". The Malay Mail Online. January 10, 2014. Archived from the original on January 22, 2014. Retrieved January 20, 2014.

- ^ "Home :: Kellogg's". Kelloggsalarabi.com. Archived from the original on November 11, 2012. Retrieved November 18, 2012.

- ^ "Kellogg Annual Report 2007 – Kellogg North America Brands". kelloggcompany.com. August 26, 2008. Archived from the original on August 26, 2008. Retrieved June 14, 2018.

- ^ "SEC Info – Kellogg Co – '10-K' for 1/1/05 – EX-21.01". Secinfo.com. Archived from the original on February 1, 2009. Retrieved June 26, 2008.

- ^ "Alaska Milk Corporation". Alaskamilk.com.ph. Archived from the original on July 28, 2012. Retrieved December 24, 2019.

- ^ "Kellogg's to build a new factory in Poland". Gosiahill.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2013.

- ^ "«Черноголовка» закрыла сделку по покупке производителя чипсов Pringles". Rbc.ru (in Russian). July 14, 2023.

- ^ "Kellogg in South Africa". December 13, 2009. Archived from the original on December 13, 2009.

External links

- Official website

- Business data for Kellanova:

- Kellogg's

- 1906 establishments in Michigan

- American companies established in 1906

- 1950s initial public offerings

- Breakfast cereal companies

- Companies based in Battle Creek, Michigan

- Companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange

- Food and drink companies established in 1906

- Food product brands

- Multinational companies headquartered in the United States

- Multinational food companies

- Snack food manufacturers of the United States

- Former Seventh-day Adventist institutions

- British royal warrant holders

- Announced mergers and acquisitions