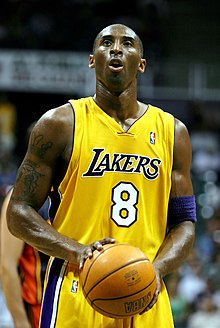

Kobe Bryant sexual assault case

The Kobe Bryant sexual assault case began on July 18, 2003, when the news media reported that the sheriff's office in Eagle, Colorado, had arrested then-professional basketball player Kobe Bryant in connection with an investigation of a sexual assault complaint,[1][2] filed by a 19-year-old hotel employee.[3]

In 2003, the sheriff's office in Eagle, Colorado, arrested Bryant in connection with an investigation of a sexual assault complaint.[4][5] News of Bryant's arrest on July 18 garnered significant news media attention.[3] Bryant had checked into The Lodge and Spa at Cordillera, a hotel in Edwards, Colorado, on June 30 in advance of having surgery near there on July 2 under Dr. Richard Steadman. A 19-year-old hotel employee accused Bryant of raping her in his hotel room on July 1. She filed a police report and authorities questioned Bryant about bruising on the accuser's neck. Bryant admitted to a sexual encounter with his accuser but insisted the sex was consensual. The case was dropped after Bryant's accuser refused to testify in the case. A separate civil suit was later filed against Bryant by the woman. The suit was settled out of court and included Bryant publicly apologizing to his accuser, the public, and family, while denying the allegations.

Arrest

Eagle County Sheriff investigators confronted Bryant with the sexual assault accusation on July 2.[3] During the July 2003 interview with investigators, Bryant initially told investigators that he did not have sexual intercourse with his accuser, a 19-year-old woman who worked at the hotel where Bryant was staying. When the officers told Bryant that she had taken an exam that yielded physical evidence, such as semen, Bryant admitted to having sexual intercourse with her, but stated that the sex was consensual.[6] When asked about bruises on the accuser's neck, Bryant admitted to "strangling" her during the encounter, stating that he held her "from the back" "around her neck", that strangling during sex was his "thing" and that he had a pattern of strangling a different sex partner (not his wife) during their recurring sexual encounters. When asked how hard he was holding onto her neck, Bryant stated, "My hands are strong. I don't know." Bryant stated that he assumed consent for sex because of the accuser's body language.[7][8]

Law enforcement officials collected evidence from Bryant and he agreed to submit to a rape test kit and a voluntary polygraph test.[9] On July 4, Sheriff Joe Hoy issued an arrest warrant for Bryant. Bryant flew from Los Angeles back to Eagle, Colorado, to surrender to police. He was immediately released on $25,000 bond, and news of the arrest became public two days after that. On July 18, the Eagle County District Attorney's office filed a formal charge against Bryant for sexual assault. If convicted, Bryant faced probation to life in prison. On July 18, after he was formally charged, Bryant held a news conference in which he adamantly denied having raped the woman. He admitted to having an adulterous sexual encounter with her but insisted it was consensual.[10]

Criminal case

In December 2003, pre-trial hearings were conducted to consider motions about the admissibility of evidence. During those hearings, the prosecution accused Bryant's defense team of attacking his accuser's credibility.[11] It was revealed that she wore underpants containing another man's semen and pubic hair to her rape exam the day after the alleged incident.[12] Detective Doug Winters stated that the yellow underwear she wore to her rape exam contained sperm from another man, along with Caucasian pubic hair. Bryant's defense stated that the exam results showed "compelling evidence of innocence" because the accuser must have had another sexual encounter immediately after the incident. She told investigators that she grabbed dirty underwear by mistake from her laundry basket when she left her home for the examination. On the day she was examined, she said she hadn't showered since the morning of the incident. The examination found evidence of vaginal trauma, which Bryant's defense team claimed was consistent with having sex with multiple partners in two days.[citation needed]

The evidence recovered by police included the T-shirt that Bryant wore the night of the incident, which had three small stains of the accuser's blood on it. The smudge was verified to be the accuser's blood by DNA testing and probably was not menstrual blood because the accuser said she had her period two weeks earlier. It was revealed that Bryant leaned the woman over a chair to have sex with her, which allegedly caused the bleeding. This was the sex act in question, as the accuser claims she told Bryant to stop, but he would not, and Bryant claims he stopped after asking if he could ejaculate on her face.[13][14]

Trina McKay, the resort's night auditor, said she saw the accuser as she was leaving to go home, and "she did not look or sound as if there had been any problem".[15] However, Bobby Pietrack, the accuser's high-school friend and a bellman at the resort, said she appeared to be very upset, and "told me that Kobe Bryant had forced sex with her".

A few weeks before the trial was scheduled to begin, the accuser wrote a letter to state investigator Gerry Sandberg clarifying some details of her first interview by Colorado police. She wrote, "I told Detective Winters that on that morning while leaving I had car troubles. That was not true. When I called in late to work that day that was the reason I gave my boss for being late. In all reality, I had simply overslept . . . I told Detective Winters that Mr. Bryant had made me stay in the room and wash my face. While I was held against my will in that room, I was not forced to wash my face. I did not wash my face. Instead, I stopped at the mirror by the elevator on that floor to clean my face up. I am extremely disappointed in myself and also very sorry to anyone misled by that mix-up of information. I said what I said because I felt that Detective Winters did not believe what had happened to me."[16]

Bryant's defense lawyer Pamela Mackey asserted that the accuser was taking an anti-psychotic drug for the treatment of schizophrenia at the time of the incident. Lindsey McKinney, who lived with the accuser, said the woman twice tried to kill herself at school by overdosing on sleeping pills. Before the alleged incident, the accuser, an aspiring singer, tried out for the television show American Idol with the song "Forgive" by Rebecca Lynn Howard, but failed to advance.[17] In addition to the woman's moral character and reputation being challenged by Bryant's defense lawyer, she received death threats and hate mail[18] and her identity was leaked multiple times.[19][20]

On September 1, 2004, Eagle County District Judge Terry Ruckriegle dismissed the charges against Bryant, after prosecutors spent more than $200,000 preparing for trial, because his accuser informed them that she was unwilling to testify.[21]

On the same day that the criminal case was dismissed, Bryant issued the following statement through his attorney:

First, I want to apologize directly to the young woman involved in this incident. I want to apologize to her for my behavior that night and for the consequences she has suffered in the past year. Although this year has been incredibly difficult for me personally, I can only imagine the pain she has had to endure. I also want to apologize to her parents and family members, and to my family and friends and supporters, and to the citizens of Eagle, Colorado.

I also want to make it clear that I do not question the motives of this young woman. No money has been paid to this woman. She has agreed that this statement will not be used against me in the civil case. Although I truly believe this encounter between us was consensual, I recognize now that she did not and does not view this incident the same way I did. After months of reviewing discovery, listening to her attorney, and even her testimony in person, I now understand how she feels that she did not consent to this encounter.

I issue this statement today fully aware that while one part of this case ends today, another remains. I understand that the civil case against me will go forward. That part of this case will be decided by and between the parties directly involved in the incident and will no longer be a financial or emotional drain on the citizens of the state of Colorado.[22]

Civil case

In August 2004, the accuser filed a civil lawsuit against Bryant over the incident.[23] In March 2005, the two parties settled that lawsuit. The terms of the settlement were not disclosed to the public.[24] The Los Angeles Times reported that legal experts estimated the settlement was more than $2.5 million.[25]

Aftermath

After the allegations, Bryant signed a seven-year contract with the Los Angeles Lakers valued at $136 million, and he regained several of his endorsements from Nike, Spalding, and Coca-Cola although his contracts with brands including Nutella and McDonald's were not renewed.[26] The sexual assault allegations had little impact on Bryant's professional basketball career as he went on to win several championships and earn accolades.[27] After issuing a statement after the case was dismissed in 2004, Bryant never discussed the case publicly[27] and he shifted emphasis to his relationship with his wife and four daughters.[28]

In 2018, following the prominence of the MeToo movement, Bryant was removed from a panel for the Animation Is Film Festival after a petition raised concerns about Bryant's alleged past violent behavior.[27] Public discussion of the case was renewed following Bryant's death in the 2020 Calabasas helicopter crash.[29]

Eight months after the initial incident, the Lodge and Spa at Cordillera remodeled and some of the furniture was sold off.[30] All furniture from the room Bryant had was disposed of and not offered for public sale.[31] The building was sold in 2019 and converted into a drug treatment facility.[32]

References

- ^ "COMPLAINT FOR SEXUAL ASSAULT AND RAPE" (PDF). United States Court for the District of Colorado. August 10, 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2008.

- ^ "Jane Doe v. Kobe Bryant: Civil Complaint for Sexual Assault and Rape". FindLaw. August 10, 2004. Archived from the original on July 19, 2013.

- ^ a b c Johnston, Lauren (February 2, 2004). "Bryant statements to police at heart of hearing". CNN. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved November 4, 2023.

- ^ "COMPLAINT FOR SEXUAL ASSAULT AND RAPE" (PDF). United States Court for the District of Colorado. August 10, 2004. Archived (PDF) from the original on July 24, 2008.

- ^ "Jane Doe v. Kobe Bryant: Civil Complaint for Sexual Assault and Rape". FindLaw. August 10, 2004. Archived from the original on July 19, 2013.

- ^ "Kobe Details Alleged Rape Night". CBS News/Associated Press. May 7, 2009

- ^ "Bryants statements to detectives - recording and transcript of interview". VailDaily. September 16, 2004. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ "Kobe Bryant Police Interview". The Smoking Gun. July 14, 2010. Retrieved August 8, 2017.

- ^ "Kobe Bryant Police Interview". The Smoking Gun. Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- ^

- "Friend Says Kobe's Accuser 'Felt Chemistry' With NBA Star" Archived May 29, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. KMGH-TV. July 23, 2003

- "Kobe Bryant charged with sexual assault" Archived March 22, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. CNN. July 22, 2003

- Moore, Booth (July 26, 2003). "Bryant gives his wife a $4-million ring". Los Angeles Times.

- Madigan, Nick (August 6, 2003). "Bryant Makes Appearance in Colorado Courtroom". New York Times.

- Zernike, Kate Zernike (October 19, 2003). "The Wifely Art of Standing By". The New York Times.

- ^ "Kobe accuser's credibility under fire". Associated Press. December 17, 2003. Archived from the original on February 22, 2004. Retrieved February 25, 2007.

- ^ "Kobe's Lawyers Introduce 'Compelling Evidence'". Fox News. October 15, 2003.

- ^ Shaw, Mark (December 21, 2003). "Rulings on statement, T-shirt will set defense strategy". USA Today.

- ^ "Kobe Bryant Police Interview" Archived May 21, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. Page 19. The Smoking Gun. accessed October 6, 2011.

- ^ "Kobe Records Released". CBS News. May 7, 2009

- ^ "Kobe Accuser's Apology Letter". The Smoking Gun. October 12, 2004

- ^ Moreno, Sylvia. "A different spotlight for Bryant's accuser" Archived May 13, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. MSNBC. August 30, 2004

- ^ Lopez, Aaron J. (March 15, 2007). "Expert: Victims' path rockier than celebrities'". The Rocky Mountain News. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved November 4, 2010.

- ^ Johnson, Kirk (July 30, 2004). "Information Leaks Prompt Questions in Kobe Bryant Case". The New York Times. Retrieved January 26, 2020.

- ^ Moreno, Sylvia (August 30, 2004). "A Different Spotlight For Bryant Accuser". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ "Rape Case Against Bryant Dismissed". MSNBC/NBC Sports. September 2, 2004. Archived from the original on October 3, 2010. Retrieved April 15, 2008.

- ^ "Kobe Bryant's apology". ESPN.com. September 2, 2004. Retrieved May 5, 2008.

- ^ "Bryant's Accuser Files Civil Suit". Los Angeles Times. August 11, 2004. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ "Suit Settlement Ends Bryant Saga". Associated Press via MSNBC/NBC Sports. March 3, 2005. Archived from the original on January 26, 2012. Retrieved December 19, 2011.

- ^ Henson, Steve (March 3, 2005). "Bryant and His Accuser Settle Civil Assault Case". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on February 10, 2022. Retrieved February 10, 2022.

- ^ Badenhausen, Kurt (September 3, 2004). "Kobe Bryant's Sponsorship Will Rebound". Forbes.

- ^ a b c Draper, Kevin (January 28, 2020). "Kobe Bryant and the Sexual Assault Case That Was Dropped but Not Forgotten". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ Henson, Steve (January 27, 2020). "What happened with Kobe Bryant's sexual assault case". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ Dionne, Evette (January 28, 2020). "We Can Only Process Kobe Bryant's Death by Being Honest About His Life". Time. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

- ^ Jack Chesnutt. "Would the real 'Kobe furniture' please stand up". MSNBC.com. Archived from the original on August 8, 2009. Retrieved June 15, 2009.

- ^ "Resort denies selling furniture from Kobe room". MSNBC.com. Associated Press. Archived from the original on July 27, 2009. Retrieved June 15, 2009.

- ^ Blevins, Jason (August 3, 2017). "Cordillera conversion to high-end drug rehab from posh spa starts next month". The Denver Post. Retrieved November 26, 2023.

External links

- Kobe Bryant Police Interview: NBA star's graphic account of hotel room encounter at The Smoking Gun

- Kobe Bryant's Disturbing Rape Case: The DNA Evidence, the Accuser's Story, and the Half-Confession at The Daily Beast

- Kobe Rebounds: The troubled rape case of the tarnished hoop star ends not in a verdict but with his apology to his accuser in Time magazine