Pande family

| Pande Dynasty पाँडे वंश/पाँडे काजी खलक Panday/Pandey | |

|---|---|

| Noble house | |

| Country | |

| Etymology | The name is derived from the Sanskrit paṇḍ (पण्ड्) which means "to collect, heap, pile up", and this root is used in the sense of knowledge. Same root as Pandit |

| Place of origin | Gorkha Kingdom |

| Founder | Ganesh Pandey (1529 A.D. – 1606 A.D.) |

| Current head | Sardar Bhim Bahadur Pande currently as a pretender |

| Final head | Rana Jang Pande |

| Titles | |

| Style(s) | |

| Connected members | |

| Connected families | |

| Traditions | List |

| Estate(s) | List |

| Deposition | 1843–1846 (by death penalty to Rana Jang Pande and Kot Massacre) |

| Cadet branches | Kala Pandes and Gora Pandes |

| Pande | |

|---|---|

| पाँडे | |

| Jāti | Chhetri |

| Languages | Nepali |

| Original state | Khas Kingdom, Gorkha Kingdom, Gorkha Empire, Nepal |

| Family names | Pande, Gora Pande, Kala Pande |

| Heraldic title | Pande Kaji |

| Throne | Lazimpat |

| Victory weapon | Khukuri |

| Related groups | Marriage relations with Kunwars, Thapas, Basnyats |

| Status | Chhetri |

The Pande family or Pande dynasty (also spelled as Pandey or Panday) (Nepali: पाँडे वंश/पाँडे काजी खलक; pronounced [paɳɖe] or [pãɽẽ]) was a Chhetri[1] political family with ancestral roots from Gorkha Kingdom that directly ruled Nepali administration affairs from the 16th century to 19th century as Mulkaji and Mukhtiyar (Prime Minister). This dynasty/family was one of the four noble families to be involved in active politics of Nepal together with the Shah dynasty, Basnyat family and Thapa dynasty before the rise of the Rana dynasty. The Pande dynasty is the oldest noble family to hold the title of Kaji.[2] This family was decimated from political power in 1843 CE[3] in the political massacre by Prime Minister Mathabar Singh Thapa as a revenge for his uncle Bhimsen's death in 1839.[4]

The family is descended from nobleman Ganesh Pande of the Gorkha Kingdom. Kalu Pande and Tularam Pande were descendants of Ganesh Pande.[5] Pande dynasty and Thapa dynasty were the two chief political families who alternatively contested for central power in the Nepalese court politics.[6][7] The Pande family was divided into two sections, Kala Pandes and Gora Pandes, who were always aligned to opposite political factions.[8] The Pande aristocratic family of Gora (White) Pande section was connected to Thapa dynasty through daughter of Chief Kazi Ranajit Pande, Rana Kumari who was married to Kaji General Nain Singh Thapa and to Rana dynasty through Nain Singh's son-in-law Bal Narsingh Kunwar.[9] The Pande family of Kala (Black) Pande section was maritally linked to Basnyat Family through Chitravati Pande who married Kaji Kehar Singh Basnyat.[10]

Ancestral Background

[edit]Ganesh Pande was the first Kaji (Prime Minister) of King Dravya Shah of Gorkha Kingdom established in 1559 A.D.[11][12] The Pandes were considered as Thar Ghar aristrocratic group who assisted in the administration of Gorkha Kingdom.[13] Kaji Kalu Pande (1714–1757) who belonged to this family[14] became a war hero after he died at the Battle of Kirtipur.[15] These Pandes were categorized with fellow Chhetri Bharadars such as Thapas, Basnyats and Kunwars.[1]

The inscription installed by son of Tularam Pande, Kapardar Bhotu Pande, on the Bishnumati bridge explains their patrilineal relationship to Ganesh Pande, Minister of Drabya Shah, the first King of Gorkha Kingdom.[5] The lineage mentions Ganesh Pande's son as Vishwadatta and Vishwadatta's son as Birudatta. Birudatta had two sons Baliram and Jagatloka. Tularam and Bhimraj were sons of Baliram and Jagatloka respectively. Kaji Kalu Pande was the son of Bhimraj. Bhotu Pande mentions Tularam, Baliram, and Birudatta respectively as his ancestors of three generations.[5] However, Historian Baburam Acharya contends a major flaw in the inscription. Ranajit Pande, the second son of Tularam was born in 1809 Vikram Samvat. Baburam Acharya assumed 25 years for each generation where he found Vishwadatta to have been born in 1707 Vikram Samvat. Thus, on this basis, he strongly concluded that Vishwadatta could not have been the son of Ganesh Pande, who was living in 1616 Vikram Samvat, when Drabya Shah was crowned King of Gorkha. He points that the names of two more generations seem to be missing.[5]

Historian Baburam Acharya speculates that Ganesh Pande was a Brahmin, however, there was no conclusive evidence to the claim. He makes the assumption based on the claim of ancestry from Ganesh Pande by Pande Brahmins of Upamanyu gotra.[5] He further assumes that Baliram and Jagatloka were Brahmins due to their Brahmin-looking name and assumes Tularam and Bhimaraj as Chhetri.[5] Pandes of the Gorkha Kingdom were categorized with fellow Chhetri Bharadars such as Thapas, Basnyats and Kunwars.[1]

Relation between Kalu and Tularam

[edit]As per Historian Baburam Acharya, Tularam was a brother (first cousin) of Bhimraj, the father of Kalu Pande.[5] However, Historian Rishikesh Shah contends that Tularam was a brother of Kalu Pande.[16]

Dominance of Damodar and catastrophe on Pandes

[edit]

Damodar Pande was appointed as one of the four Kajis by King Rana Bahadur Shah after removal of Chautariya Bahadur Shah of Nepal on 1794.[17] Damodar was most influential and dominant in the court faction irrespective of post of Chief Kazi (Mulkazi) being held by Kirtiman Singh Basnyat.[17] Pandes were the most dominant noble family. Later due to continuous irrational behaviour of King Rana Bahadur Shah, situation of civil war arose where Damodar was the main opposition to the King.[18] He was forced to flee to the British-controlled city of Varanasi in May, 1800 after military men parted with influential Kaji Damodar.[19][18]

After Queen Rajrajeshwari finally managed to assume the regency on 17 December 1802,[20][21] later in February she elected Damodar Pande as the Mul Kaji (Chief Kaji).[22] Damodar Pande, Pande family and faction, were responsible for treaty with British which incensed exiled King Rana Bahadur.[23] The Treaty of 1801 was also unilaterally annulled by the British on 24 January 1804.[24][25][26][27] The suspension of diplomatic ties also gave the Governor General a pretext to allow the ex-King Rana Bahadur to return to Nepal unconditionally.[25][27]

Troops sent by Kathmandu Durbar changed their allegiance when they came face to face with the incoming ex-King Rana Bahadur.[28] Damodar Pande and members of Pande factions were arrested at Thankot where they were waiting to greet the ex-King with state honors and take him into isolation.[28][26] After Rana Bahadur's reinstatement to power, he ordered Damodar Pande, along with his two eldest sons, who were completely innocent, to be executed on 13 March 1804; similarly some members of his faction were tortured and executed without any due trial, while many others managed to escape to India. Among those who managed to escape to India were Damodar Pande's sons Karbir Pande and Rana Jang Pande.[29][29][30]

Resurrection of Pandes

[edit]

During the Anglo-Nepalese War, Rana Jang Pande had informed Ranabir Singh Thapa that the British would be off guard during Christmas. Following this advice, Ranabir Singh was able to obtain a major victory during a battle in Parsa. This won the Pandes the trust of Ranabir Singh, which eventually led to their pardon by King Girvan and subsequent return to Nepal.[31] In November 1834, Ranjung Pande, the youngest son of Damodar Pande, petitioned the king to restore the lands and properties of the Pande family. To the surprise of the court, the king accepted the petition. The king, however, had not taken immediate action on this request. With royal support, Ranjung immediately sent a request to the Chinese Amban in Lhasa requesting they restore the families historical relation in Tibet. He had also accused Bhimsen Thapa of supporting the British which at the time were one of China's main enemies. After this, the Amban had then requested to the king that Ranjung be sent as a diplomat to Peking in the next diplomatic quinquennial year.[32] By 1836, Rana Jang Pande was stationed as a captain in the army in Kathmandu. He was aware of the disunity between Samrajya Laxmi and Bhimsen Thapa; and thus he had secretly expressed his loyalty to Samrajya Laxmi and had vowed to help her in bringing Bhimsen down for all the wrongs he had committed against his family.[33] Factions in the Nepalese court had also started to develop around the rivalry between the two queens, with the Senior Queen supporting the Pandes, while the Junior Queen supporting the Thapas.[34] Pandes spread news of child born out of an adulterous relationship between Mathabar Singh Thapa and his widowed sister-in-law and the resulting public disgrace forced Mathabar to leave Kathmandu and reside in his ancestral home in Pipal Thok, Borlang, Gorkha.[33] The weakening of power of Thapas in absence of Mathabar and Bhimsen in Kathmandu[35][36] helped King Rajendra Bikram Shah to establish a new personal battalion, Hanuman Dal, and by February 1837, both Rana Jang Pande and his brother, Ranadal Pande, had been promoted to the position of a Kaji; and Ranajang was made a personal secretary to the King, while Ranadal Pande was made the governor of Palpa.[37] Ranajang, the leader of Pandes, was also made the chief palace guard, the position formerly occupied by Ranabir Singh and then Bhimsen which curtailed Bhimsen's access to the royal family and reduced Thapas from the power.[37] After the incarceration of the Thapas in the poisoning case in 1837, a new government with joint Mukhtiyars was formed with Ranga Nath Poudyal as the head of civil administration, and Dalbhanjan Pande and Ranajang Pande as joint heads of military administration.[38] This appointment established the Pandes as the dominant faction in the court, and they started to make preparations for war with the British in order to win back the lost territories of Kumaon and Garhwal.[39] While such war posturing was nothing new, the din the Pandes created alarmed not just the Resident Hodgson[39] but the opposing court factions as well, who saw their aggressive policy as detrimental to the survival of the country.[40] After about three months in power, under pressure from the opposing factions, the King removed Ranajang as Mukhtiyar and Ranganath Paudel, who was favorably inclined towards the Thapas, was chosen as the sole Mukhtiyar.[41][42][43][40]

Fearful that the Pandes would re-establish their power, Fatte Jang Shah, Rangnath Poudel, and the Junior Queen Rajya Laxmi Devi obtained from the King the liberation of Bhimsen, Mathabar, and the rest of the party, about eight months after they were incarcerated for the poisoning case.[42][43][44] However, Ranganath Poudel, finding himself unsupported by the King, resigned from the Mukhtiyari, which was then conferred on Pushkar Shah; but Puskhar Shah was only a nominal head, and the actual authority was bestowed on Ranajang Pande.[45] Sensing that a catastrophe was going to befall the Thapas, Mathabar Singh fled to India while pretending to go on a hunting trip; Ranbir Singh gave up all his property and became a sanyasi, titling himself Abhayanand Puri; but Bhimsen Thapa preferred to remain in his old home in Gorkha.[44][46] The Pandes were now in full possession of power; they had gained over the King to their side by flattery. The Senior Queen had been a firm supporter of their party; and they endeavored to secure popularity in the army by promises of war and plunder.[45]

At the beginning of 1839, Ranajang Pande was made the sole Mukhtiyar. However, knowledge about Ranajang's war preparations and his communication with other princely states of India, fomenting anti-British sentiments, alarmed the Governor-General of the time, Lord Auckland, who mobilized some British troops near the border of Nepal.[46][47] In order to resolve this diplomatic fiasco, Bhimsen was recalled from Gorkha releasing consfication[48][49] after which he suggested some of the battalions under Ranajang's command to be given to other courtiers, thus severely weakening Ranajang's military power.[50] After the ostracization of Thapas on fabricated cases with forged papers,[51][52] Bhimsen, the leader of Thapas, attempted suicide due to indignity[53] after hearing rumors of his wife to be publicly disgraced on 28 July 1839.[54][53] Five months after Bhimsen's death, Ranajang Pande was again made Mukhtiyar (prime minister); but Ranajang's inability to control the general lawlessness in the country forced him to resign from prime minister's office, which was then conferred on Pushkar Shah, based on Samrajya Laxmi's recommendation.[55] Pushkar Shah and his Pande associates were dismissed, and Fatte Jang Shah was appointed Mukhtiyar (prime minister) in November 1840 due to British intervention.[56] After the death of Senior Queen Samrajya Laxmi, the Nepalese court was split into three factions centered around the King, the Junior Queen, and the Crown Prince. Fateh Jang and his administration supported the King, the Thapas supported the Junior Queen, while the Pandes supported the Crown Prince. The resurgent Thapa coalition succeeded in sowing animosity between Fateh Jang's ministry and the Pande coalition, who were swiftly imprisoned.[57]

Ultimate Fall of Pandes

[edit]Under immense pressure from the Queen and the nobility, along with the backing from army and the general populace, the King in January 1843 handed the highest authority of the state to his Junior Queen, Rajya Laxmi, curtailing both his own and his son's power.[58][59] The Queen, seeking support of her own son's claims to the throne over those of Surendra, invited eldest Thapa dynast Mathabar Singh Thapa back after almost six years in exile.[60] Upon his arrival in Kathmandu in April 1843, an investigation of his uncle Bhimsen's death took place, and a number of his Pande enemies were massacred.[4] As for Ranajang Pande, he had by that time contracted mental illness and would not have posed any threat to Mathabar. Nevertheless, Ranajang was paraded through the streets and made to witness the execution of his family members, after which he was forced to commit suicide by poison.[4]

Pande Palaces

[edit]

As Thapathali was abode of the Thapas, Lazimpat was abode of Pandes. Lazimpat Durbar was property of Kaji Bir Keshar Pande. At the time of the Kot massacre on 14 September 1846, Kaji Bir Keshar Pande was massacred there and lazimpat Durbar was occupied by Kaji Col.Tribikram Singh Thapa, maternal uncle of Rana rulers.[61]

Pande family members

[edit]Kala Pandes

[edit]| No. | Members | Image | Position | Years in the position | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kalu Pande |  |

Kaji of Gorkha Kingdom | 1744–1747 to 1757 A.D. | Father of all Kala Pandes |

| 2 | Vamsharaj Pande |  |

Dewan-Kaji (Chief Minister) and Pradhan-senapati | 1777–1785 A.D. | eldest son of Kalu and head of Pandes before 1785 |

| 3 | Damodar Pande |  |

Mulkaji (Prime Minister) and Commander-in-Chief | 1803–1804 A.D. (though most influential Kaji between 1794 and 1804) | youngest son of Kalu and head of Pandes between 1785 and 1804 |

| 4 | Rana Jang Pande |  |

Mukhtiyar (Prime Minister) and Commander-in-Chief | 1837–1837 A.D. and 1839–1840 A.D. | the last Kala Pande leader before deposition of Pandes in 1843 |

| 5 | Karbir Pande | Kaji | the significant Kala Pande courtier in 1837–1843 | grandson of Kalu Pande[62] and killed in 1843. |

Gora Pandes

[edit]| No. | Members | Image | Position | Years in the position | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Tularam Pande | Sardar | died 1768 | Father of all Gora Pandes, a military commander of King Prithvi Narayan Shah | |

| 2 | Ranajit Pande | Mulkaji (Chief Kaji) | briefly in 1804 A.D.[17] | son of Tularam Pande;[62] the only Gora Pande to become highest ranked Mulkaji | |

| 3 | Dalbhanjan Pande | Kaji and later General | briefly headed military administration in 1837 A.D. | grandson of Tularam Pande[62] and the significant Gora Pande courtier between 1810s to 1846 | |

| 4 | Bir Keshar Pande | Kaji and Kapardar[10] | grandson of Tularam Pande[62] and owner of Lazimpat Durbar | ||

| 5 | Bhotu Pande | Kapardar | son of Tularam Pande[62] a military officer in the Sino-Nepalese War | ||

| 6 | Ranagambhir Pande | Kaji[10] | the significant Gora Pande courtier in 1846 | grandson of Tularam Pande[62] and died in the Kot massacre of 1846 |

Pande memorials and legacy

[edit]

The burial ground on hill top of Kaji Kalu Pande is a popular hiking spot. It lies in Chandragiri, western outskirts of Kathmandu from where Gorkha can be seen.[63] Rastra Bhaktiko Jhalak: Panday Bamsa ko Bhumika (Transl. Glimpse of Patriotism: Role of Pande dynasty) is a book written on Pande dynasty by Sardar Bhim Bahadur Pande.[64]

Descendants

[edit]First Mandarin and Historian-diplomat Sardar Bhim Bahadur Pande is the seventh lineal descendant of Kaji Kalu Pande.[65] Late Maj.Gen Sagar Bahadur Pande, Businessman Himalaya Bahadur Pande, Banker Prithvi Bahadur Pande, General Pawan Bahadur Pande, who retired as Number 2 of the Nepal Army, Dr.Shanta Bahadur Pande are the sons of First Mandarin, diplomat-historian Sardar Bhim Bahadur Pande[66] and eighth descendant of Kaji Kalu Pande.[65]

-

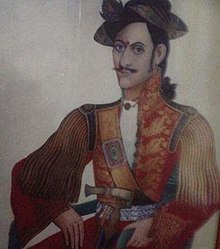

Portrait of Kalu Pande

-

Kalu Pande during Unification Campaign

-

Kalu Pande memorial park

-

Rana Jang Pande, the last Pande leader

-

Bhim Bahadur Pande, the 20th century Pande descendant

-

Letter sent to PM Bhimsen Thapa and Kazi Ranadhoj Thapa by (Pvt. seal L to R) Bakhat Singh Sardar, Dalbhanjan Pande (Pande Kazi), Ranabir Singh Thapa, Kaji Narsingh Thapa (Elder Amar Singh Thapa's another son) and sundry captains

-

Kaji Kalu Pande statue at Dahachowk

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c Edwards, Daniel W. (1975-02-01). "Nepal on the eve of the Rana ascendancy" (PDF). Contributions to Nepalese Studies. 2 (1): 99–118 – via Digital Himalaya.

- ^ Joshi & Rose 1966, p. 23.

- ^ Rose 1971, p. 105.

- ^ a b c Acharya 2012, pp. 179–181.

- ^ a b c d e f g Acharya 1979, p. 43.

- ^ Pradhan 2012, p. 9.

- ^ Majupuria, Trilok Chandra; Majupuria, Indra (1979). "Thapa and Pande family animosity". p. 26.

- ^ Pradhan 2001, p. 6.

- ^ JBR, PurushottamShamsher (1990). Shree Teen Haruko Tathya Britanta (in Nepali). Bhotahity, Kathmandu: Vidarthi Pustak Bhandar. ISBN 99933-39-91-1.

- ^ a b c Regmi 1995, p. 44.

- ^ Regmi 1975, p. 30.

- ^ Wright 1877, p. 278.

- ^ Pradhan 2012, p. 8.

- ^ Singh 1997, p. 126.

- ^ Wright, Daniel (1990). History of Nepal. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. Retrieved 7 November 2012. Page 227

- ^ Shaha 1990, p. 160.

- ^ a b c Pradhan 2012, p. 12.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, pp. 28–32.

- ^ Pradhan 2012, p. 13.

- ^ Pradhan 2012, p. 14.

- ^ Acharya 2012, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 43.

- ^ Nepal 2007, p. 51.

- ^ Amatya 1978.

- ^ a b Pradhan 2012, pp. 14, 25.

- ^ a b Nepal 2007, p. 56.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 45.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, pp. 49–55.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 54.

- ^ Nepal 2007, p. 57.

- ^ Nepal 2007, pp. 104–105.

- ^ Pradhan 2012, p. 158.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 155.

- ^ Nepal 2007, p. 108.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 156.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 157.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 158.

- ^ Nepal 2007, p. 106.

- ^ a b Pradhan 2012, p. 163.

- ^ a b Pradhan 2012, p. 164.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 160.

- ^ a b Oldfield 1880, p. 311.

- ^ a b Nepal 2007, p. 109.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 161.

- ^ a b Oldfield 1880, p. 313.

- ^ a b Nepal 2007, p. 110.

- ^ Acharya 2012, pp. 161–162.

- ^ Nepal 2007, p. 111.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 162.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 163.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 163-164.

- ^ Oldfield 1880, p. 315-316.

- ^ a b Acharya 2012, p. 164.

- ^ Oldfield 1880, p. 316.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 167.

- ^ Acharya 2012, p. 170.

- ^ Acharya 2012, pp. 173–176.

- ^ Acharya 2012, pp. 176–177.

- ^ Whelpton 2004, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Acharya 2012, pp. 177–178.

- ^ JBR, PurushottamShamsher (2007). Ranakalin Pramukh Atihasik Darbarharu [Chief Historical Palaces of the Rana Era] (in Nepali). Vidarthi Pustak Bhandar. ISBN 978-9994611027. Retrieved 10 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f Pradhan 2012, p. 198.

- ^ "Kalu Pandey Burial Ground being popular among Kathmandu hikers". thehimalayantimes.com. 26 March 2017. Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- ^ "Ratna Pustak Bhandar – The Oldest Book Store – Kathmandu, Nepal". ratnabooks.com. Retrieved 2017-06-11.

- ^ a b "ampnews/2013-12-15/6239". nepal.ekantipur.com. Retrieved 2017-06-11.

- ^ "Obituary: End of an era". m.setopati.net. Archived from the original on 2015-04-29. Retrieved 2017-06-11.

Bibliography

[edit]- Acharya, Baburam (2012), Acharya, Shri Krishna (ed.), Janaral Bhimsen Thapa : Yinko Utthan Tatha Pattan (in Nepali), Kathmandu: Education Book House, p. 228, ISBN 9789937241748

- Acharya, Baburam (March 1, 1979), "The Unification of Nepal" (PDF), Regmi Research Series, 11 (3): 40–48

- Wright, Daniel (1877), History of Nepal, ISBN 9788120605527

- Joshi, Bhuwan Lal; Rose, Leo E. (1966), Democratic Innovations in Nepal: A Case Study of Political Acculturation, University of California Press, p. 551

- Oldfield, Henry Ambrose (1880), Sketches from Nipal, Vol 1, vol. 1, London: W.H. Allan & Co.

- Pradhan, Kumar L. (2012), Thapa Politics in Nepal: With Special Reference to Bhim Sen Thapa, 1806–1839, New Delhi: Concept Publishing Company, p. 278, ISBN 9788180698132

- Regmi, Mahesh Chandra (1995), Kings and political leaders of the Gorkhali Empire, 1768–1814, Orient Longman, p. 83, ISBN 9788125005117

- Pradhan, Kumar L. (2001). Brian Hodgson at the Kathmandu residency, 1825-1843. Spectrum Publications. ISBN 9788187502159.

- Regmi, D.R. (1975), Modern Nepal, ISBN 9780883864913

- Shaha, Rishikesh (1982), Essays in the Practice of Government in Nepal, Manohar, p. 44, OCLC 9302577

- Shaha, Rishikesh (1990), Modern Nepal 1769–1885, Riverdale Company, ISBN 0-913215-64-3

- Adhikari, Indra (12 June 2015), Military and Democracy in Nepal, Routledge, ISBN 9781317589068

- Nepal, Gyanmani (2007), Nepal ko Mahabharat (in Nepali) (3rd ed.), Kathmandu: Sajha, p. 314, ISBN 9789993325857

- Hamal, Lakshman B. (1995), Military history of Nepal, Sharda Pustak Mandir

- Singh, Nagendra Kumar (1997), Nepal: Refugee to Ruler : a Militant Race of Nepal, APH Publishing Corporation, ISBN 9788170248477

- Rose, Leo E. (1971). Nepal; strategy for survival. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520016439.