KV49

| KV49 | |

|---|---|

| Burial site of unknown | |

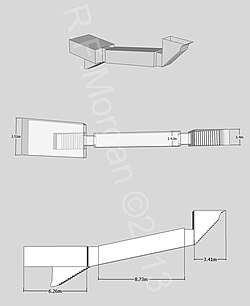

Schematic of the unfinished KV49 | |

| Coordinates | 25°44′23.4″N 32°36′02.3″E / 25.739833°N 32.600639°E |

| Location | East Valley of the Kings |

| Discovered | January 1906 |

| Excavated by | Edward R. Ayrton |

← Previous KV48 Next → KV50 | |

Tomb KV49, located in the Valley of the Kings, in Egypt is a typical Eighteenth Dynasty corridor tomb. It was the first of a series of tombs discovered in 1906 by Edward R. Ayrton in the course of his excavations on behalf of Theodore M. Davis. The tomb was abandoned before it was completed, and the work was halted as the stairwell in the single chamber was being cut. It was probably used as a store for royal linen,[1] or was used as a mummy-restoration area in the later New Kingdom.[2]

Location, discovery, and layout

[edit]The tomb is located in a side valley that runs towards the tomb of Amenhotep II, KV35. The valley is formed by two rocky promontories. On the northern side are the tombs KV12 and KV9; the southern side had not been investigated and "presented to the eye a surface level of loose rubbish, unbroken by depressions."[3] Ayrton began clearing to the bedrock as part of Davis' "system of exhaustion" strategy,[3] working methodically from east to west.

KV49 was the first tomb uncovered and is located on the northern side of the promontory, running south into the rock. The entrance was filled with limestone chips, amongst which were several ostraca. One depicts an official worshipping, while the other, drawn in red and black ink depicts a man presenting an offering to the deified Queen Ahmose-Nefertari.[3]

The tomb is a typical mid-Eighteenth Dynasty corridor tomb, although unfinished. It consists of a flight of stairs that lead down to the first doorway. Beyond this is a long sloping corridor, the doorway at the far end of which was once sealed with stones and plaster. This opens onto a square chamber, in the floor of which the cutting of a staircase was begun but never finished.[3]

Contents

[edit]The single chamber contained scraps of mummy cloth, fragments of white-washed ceramic storage jars, and in a small pit over the unfinished stairs, an ostracon naming "Hay, overseer of workmen in the Place of Truth." He is depicted making offerings to the goddess Meretseger on one side; on the other is a list of workmen. Also found were several rough game boards carved from limestone slabs.[3] A broken wooden label bearing the inscription "corpse oil" was also found.[1]

Graffiti and later use

[edit]Ayrton noted hieratic graffiti listing workmen written in red ink written above the entrance.[3] They record two visits of officials to the tomb in the reigns of Ramesses XI or Smendes I to deliver large quantities of royal linen.[4]

The first reads:

1 Peret 25. Coming and bringing the royal linen, 20 [cloths?]. Assorted bedspreads [ẖyrr], 5; shawls, 15: total, 20. The Scribe Butehamun, Pakhoir, Pennesttawy, son of Nesamenope, Hori, Takany, Amenhotep, Kaka, Nakhtamenwese, and Amen[neb]nesttawynakte.[4]

The second reads:

Finishing on the second occasion; bringing clothing, 3 Peret 5.

The men who brought [it]: Pait, the Scribe Butehamun, Iyamennuef, Pakhoir, Tjauemdi..., Hori, son of Kadjadja, Takairnayu, Nesamenope.

Royal linen, shawls, 45; long shawls, 5: total, 50.[4]

The tomb seems to have been employed as a storeroom for temple linen at the end of the New Kingdom; the game boards and ostraca likely date to this period of the tomb's use.[1] Nicholas Reeves suggests that the tomb was used for the restoration and rewrapping of royal mummies in the late New Kingdom. The name Butehamun occurs once on the restoration dockets, that of Ramesses III. Reeves therefore finds it likely that the tomb was provisioned with cloth for the rewrapping of the mummy of that king, whose tomb, KV11, is located relatively close by.[2]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Reeves, Nicholas; Wilkinson, Richard H. (1996). The Complete Valley of the Kings: Tombs and Treasures of Egypt's Greatest Pharaohs (2010 paperback ed.). London: Thames and Hudson. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-500-28403-2.

- ^ a b Reeves, C. N. (1990). Valley of the Kings: Decline of a royal necropolis. London: Kegan Paul International. pp. 130–131. ISBN 0-7103-0368-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Davis, Theodore M.; Maspero, Gaston; Ayrton, Edward; Daressy, George; Jones, E. Harold (1908). The Tomb of Siptah; The Monkey Tomb and the Gold Tomb. London: Archibald Constable and Co., Ltd. pp. 16–17. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Peden, Alexander J. (2001). The Graffiti of Pharaonic Egypt: Scope and Roles of Informal Writings (c. 3100–332 B.C.). Leiden: Brill. pp. 206–207. ISBN 978-90-04-12112-6. Retrieved 15 August 2021.

External links

[edit]- Theban Mapping Project: KV49 includes detailed maps of most of the tombs.