The Empire Strikes Back

| The Empire Strikes Back | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster by Roger Kastel | |

| Directed by | Irvin Kershner |

| Screenplay by | |

| Story by | George Lucas |

| Produced by | Gary Kurtz |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Peter Suschitzky |

| Edited by | Paul Hirsch |

| Music by | John Williams |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | 20th Century-Fox |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 124 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $30.5 million |

| Box office | $538–549 million[i] |

The Empire Strikes Back (also known as Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back) is a 1980 American epic space opera film directed by Irvin Kershner from a screenplay by Leigh Brackett and Lawrence Kasdan, based on a story by George Lucas. The sequel to Star Wars (1977),[ii] it is the second film in the Star Wars film series and the fifth chronological chapter of the "Skywalker Saga". Set three years after the events of Star Wars, the film recounts the battle between the malevolent Galactic Empire, led by the Emperor, and the Rebel Alliance, led by Luke Skywalker and Princess Leia. As the Empire goes on the offensive, Luke trains to master the Force so he can confront the Emperor's powerful disciple, Darth Vader. The ensemble cast includes Mark Hamill, Harrison Ford, Carrie Fisher, Billy Dee Williams, Anthony Daniels, David Prowse, Kenny Baker, Peter Mayhew, and Frank Oz.

Following the success of Star Wars, Lucas hired Brackett to write the sequel. After she died in 1978, he outlined the whole Star Wars saga and wrote the next draft himself, before hiring Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981) writer Kasdan to enhance his work. To avoid the stress he faced directing Star Wars, Lucas handed the responsibility to Kershner and focused on expanding his special effects company Industrial Light & Magic instead. Filmed from March to September 1979 in Finse, Norway, and at Elstree Studios in England, The Empire Strikes Back faced production difficulties, including actor injuries, illnesses, fires, and problems securing additional financing as costs rose. Initially budgeted at $8 million, costs had risen to $30.5 million by the project's conclusion.

Released on May 21, 1980, the highly anticipated sequel became the highest-grossing film that year, earning approximately $401.5 million worldwide. Unlike its lighthearted predecessor, Empire met with mixed reviews from critics, and fans were conflicted about its darker and more mature themes. The film was nominated for various awards and won two Academy Awards, two Grammy Awards, and a BAFTA, among others. Subsequent releases have raised the film's worldwide gross to $538–549 million and, adjusted for inflation, it is the 13th-highest-grossing film in the United States and Canada.

Since its release, The Empire Strikes Back has been critically reassessed and is now often regarded as the best film in the Star Wars series and among the greatest films ever made. It has had a significant impact on filmmaking and popular culture and is often considered an example of a sequel superior to its predecessor. The climax, in which Vader reveals he is Luke's father, is often ranked as one of the greatest plot twists in cinema. The film spawned a variety of merchandise and adaptations, including video games and a radio play. The United States Library of Congress selected it for preservation in the National Film Registry in 2010. Return of the Jedi (1983) followed Empire, concluding the original Star Wars trilogy. Prequel and sequel trilogies have since been released.

Plot

[edit]Three years after the destruction of the Death Star,[iii] the Imperial fleet, led by Darth Vader, dispatches probe droids across the galaxy in search for the Rebel Alliance. One probe locates the rebel base on the ice planet Hoth. While Luke Skywalker is scouting near the base, a wampa captures him before he can investigate a meteorite, but he escapes by using the Force to retrieve his lightsaber and wound the beast. Before Luke succumbs to hypothermia, the Force spirit of his deceased mentor, Obi-Wan Kenobi, instructs him to go to the swamp planet Dagobah to train as a Jedi Knight under the Jedi Master Yoda. Han Solo discovers Luke and insulates him against the weather inside his deceased tauntaun mount until they are rescued the next morning.

Alerted to the Rebels' location, the Empire launches a large-scale attack using AT-AT walkers, forcing the Rebels to evacuate the base. Han, Princess Leia, C-3PO and Chewbacca escape aboard the Millennium Falcon, but the ship's hyperdrive malfunctions. They hide in an asteroid field, where Han and Leia grow closer amid the tension. Vader summons several bounty hunters, including Boba Fett, to find the Falcon. Evading the Imperial fleet, Han's group travels to the floating Cloud City on the gas planet Bespin, which is governed by his old friend Lando Calrissian. Fett tracks them there, and Vader forces Lando to surrender the group to the Empire, knowing Luke will come to their aid.

Meanwhile, Luke travels with R2-D2 in his X-wing fighter to Dagobah, where he crash-lands. He meets Yoda, a diminutive creature who reluctantly accepts him as his Jedi apprentice after conferring with Obi-Wan's spirit. Yoda trains Luke to master the light side of the Force and resist negative emotions that will seduce him to the dark side, as they did Vader. Luke struggles to control his anger and impulsiveness and fails to comprehend the nature and power of the Force until he witnesses Yoda use it to levitate the X-wing from the swamp. Luke has a premonition of Han and Leia in pain and, despite Obi-Wan's and Yoda's protestations, abandons his training to rescue them. Although Obi-Wan believes Luke is their only hope, Yoda asserts that "there is another."

Leia confesses her love for Han before Vader freezes him in carbonite to test whether the process will safely imprison Luke. Han survives and is given to Fett, who intends to collect his bounty from Jabba the Hutt. Lando frees Leia and Chewbacca, but they are too late to stop Fett's escape. The group fights its way back to the Falcon and flees the city. Luke arrives and engages Vader in a lightsaber duel over the city's central air shaft. Vader defeats Luke, severing his right hand and separating him from his lightsaber. He urges Luke to embrace the dark side and help him destroy his master, the Emperor, so they may rule the galaxy together. Luke refuses, citing Obi-Wan's claim that Vader killed his father, prompting Vader to reveal that he is Luke's father. Distraught, Luke plunges down the air shaft and is ejected beneath the floating city, latching onto an antenna. He reaches out through the Force to Leia, and the Falcon returns to rescue him. They are attacked by TIE fighters but narrowly evade capture by Vader's Star Destroyer when R2-D2 repairs the Falcon's hyperdrive and the vessel escapes.

After the group joins the rebel fleet, Luke's missing hand is replaced by a robotic prosthesis. He, Leia, C-3PO, and R2-D2 observe as Lando and Chewbacca depart on the Falcon to find Han.[iv]

Cast

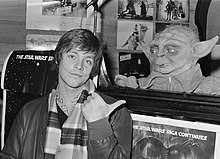

[edit]- Mark Hamill as Luke Skywalker: A pilot in the Rebel Alliance and apprentice Jedi[6]

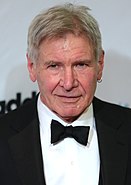

- Harrison Ford as Han Solo: A smuggler and captain of the Millennium Falcon[7][8]

- Carrie Fisher as Leia Organa: A leader in the Rebel Alliance[9]

- Billy Dee Williams as Lando Calrissian: The administrator of Cloud City[10]

- Anthony Daniels as C-3PO: A humanoid protocol droid[11]

- David Prowse / James Earl Jones (voice) as Darth Vader: A powerful Sith Lord[12][13]

- Peter Mayhew as Chewbacca: Han's loyal Wookiee friend and co-pilot[14][15]

- Kenny Baker as R2-D2: An astromech droid[16]

- Frank Oz (puppeteer/voice) as Yoda: A diminutive, centuries-old Jedi Master[17][18]

The film also features Alec Guinness as Ben (Obi-Wan) Kenobi, and John Hollis as Lobot, Lando's aide.[19] The Rebel force includes General Rieekan (portrayed by Bruce Boa),[19] Major Derlin (John Ratzenberger),[20][21] Cal Alder (Jack McKenzie),[21] Dak Ralter (John Morton),[21][22] Wedge Antilles (Denis Lawson),[19] Zev Senesca (Christopher Malcolm),[23][24] and Hobbie Klivian (Richard Oldfield).[25]

The Empire's forces include Admiral Piett (Kenneth Colley), Admiral Ozzel (Michael Sheard), General Veers (Julian Glover), and Captain Needa (Michael Culver).[19] The Emperor is voiced by Clive Revill and portrayed physically by Elaine Baker.[26][27][v] The bounty hunter Boba Fett is portrayed physically by Jeremy Bulloch and voiced by Jason Wingreen (who remained uncredited until 2000).[19][28] Other bounty hunters include Dengar (portrayed by Morris Bush) and the humanoid lizard Bossk (Alan Harris).[29][30]

Production

[edit]Development

[edit]

Following the unexpected financial success and cultural impact of Star Wars (1977), a sequel was swiftly put into production.[a] In case Star Wars had failed, creator George Lucas had contracted Alan Dean Foster to write a low-budget sequel (later released as the novel Splinter of the Mind's Eye).[35][36] Once the success of Star Wars was evident, Lucas was reluctant to direct the sequel because of the stress of making the first film and its impact on his health.[b] The popularity of Star Wars brought Lucas wealth, fame and positive attention from the public, but it also brought negative attention in the form of threats and many requests for financial backing.[31]

Conscious that the sequel needed to exceed the original's scope—making it a bigger production—and that his production effects company Lucasfilm was relatively small and operating out of a makeshift office, Lucas considered selling the project to 20th Century-Fox in exchange for a profit percentage.[17][37][39] He had profited substantially from Star Wars and did not need to work, but was too invested in his creation to entrust it to others.[c] Lucas had concepts for the sequel but no solid structure.[35] He knew the story would be darker, would explore more mature themes and relationships, and would continue to explore the nature of the Force.[17] Lucas intended to fund the production independently, using his $12 million profit from Star Wars to relocate and expand his special effects company Industrial Light & Magic (ILM) and establish his Skywalker movie ranch in Marin County, California, with the remainder as collateral for a loan from Bank of America for the film's $8 million budget.[d]

Fox had the right of first negotiation and refusal to participate in any potential sequel. Negotiations began in mid-1977 between the studio and Lucas's representatives. Fox had already given Lucas controlling interest in the series' merchandising and sequels because it had thought Star Wars would be worthless.[40] Terms were agreed quickly for the sequel compared to the original, in part because Fox executive Alan Ladd Jr. had been supportive of the original and was eager for the sequel.[44] The 100-page contract was signed on September 21, 1977, dictating that Fox would distribute the film but have no creative input, in exchange for 50% of the gross profits on the first $20 million earned, with the percentage increasing to 77.5% in the producers' favor if it exceeded $100 million. Filming had to begin by January 1979 for release on May 1, 1980.[41][45] The deal offered the possibility of significant financial gain for Lucas, but he risked financial ruin if the sequel failed.[17][46]

To mitigate some of the risk, Lucas founded The Chapter II Company to control the film's development and absorb its liabilities.[47] He signed a contract between the company and Lucasfilm, granting himself 5% of the box office gross profits.[48] He also founded Black Falcon to license Star Wars merchandising rights, using the income to subsidize his ongoing projects.[49] Development for the sequel began in August 1977, under the title Star Wars Chapter II.[50]

Lucas considered replacing producer Gary Kurtz with Howard Kazanjian because Kurtz had not fulfilled his role and left problems unresolved while filming Star Wars. Kurtz convinced him otherwise by trading on his longtime loyalty to Lucas and knowledge of the Star Wars property.[51] Lucas took an executive producer role, enabling him to focus on his businesses and the development of Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981).[17][41][52] By late 1977, Kurtz began hiring key crew members, including production designer Norman Reynolds, consultant John Barry, makeup artist Stuart Freeborn, and first assistant director David Tomblin.[17][53] Lucas rehired artists Ralph McQuarrie and Joe Johnston to maintain visual consistency with Star Wars, and the three began conceptualizing the Hoth battle in December.[54] By this point, the budget had increased to $10 million.[55] Lucas wanted a director who would support the material and accept that he was ultimately in charge.[17] He considered around 100 directors, including Alan Parker and John Badham, before hiring his old acquaintance Irvin Kershner in February 1978.[17][56] Kershner was reluctant to direct the sequel to a film as successful as Star Wars, and his friends warned him against taking the job, believing he would be blamed if it failed.[17][57] Lucas convinced Kershner it was not so much a sequel as a chapter in a larger story; he also promised him he could make the film his own way.[57]

Writing

[edit]Lucas began formulating ideas in August 1977. These included the Emperor, Luke's lost sister, and an explanation of facial injuries Hamill had suffered from an accident after filming Star Wars (Lucas told Hamill that, had he died, his character would have been replaced, not recast).[58] Hamill recounted being told the sister character might be Leia, which he found disappointing.[59] Lucas had written Star Wars but did not enjoy developing lore for an original universe.[60] Science-fiction writer Leigh Brackett, whom Lucas met through a friend, excelled in quick-paced dialogue. He hired her for $50,000, aware that she had cancer.[e]

Between November 28 and December 2, 1977, Lucas and Brackett held a story conference.[35][62] Lucas had core ideas in mind but wanted Brackett to piece them together.[17][60] He envisioned one central plot complemented by three main subplots, set across 60 scenes, 100 script pages, and a two-hour runtime.[63] They formed a general outline and ideas that included the Wookiee homeworld, new alien species, the Galactic Emperor, a gambler from Han's past, water and city planets, Luke's lost twin sister, and a diminutive, froglike creature, Minch Yoda.[35][64][65] Lucas drew on influences including The Thing from Another World (1951), the novel Dune (1965), and the television series Flash Gordon (1954).[66] Around this time, Kurtz conceived the title The Empire Strikes Back.[f] He said they avoided calling it Star Wars II because films with "II" in their titles were seen as inferior.[41]

Brackett completed her first draft in February 1978, titled Star Wars sequel, from the adventures of Luke Skywalker.[57][61][68] The draft contained a city in the clouds, a chase through an asteroid belt, a greater focus on the love triangle between Luke, Han, and Leia (who is portrayed as a damsel in distress), the battle of Hoth and a climactic duel between Luke and Darth Vader. The ghosts of his father and Obi-Wan visit Luke, leaving Vader a separate character. The draft reveals Luke has a sister (not Leia), Han goes on a mission to recruit his powerful stepfather, and Lando is a clone from the Clone Wars.[35] Lucas made detailed notes and attempted to contact Brackett, but she had been hospitalized, and died of cancer a few weeks later, on March 18.[17][69][70]

Rewrite

[edit]The strict schedule left Lucas no choice but to write the second draft himself.[17][61][70] Though Brackett's draft followed Lucas's outline, he found she had portrayed the characters differently than he intended.[71] Lucas completed his handwritten, 121-page draft on April 1. He found the process more enjoyable than on Star Wars because he was familiar with the universe, but struggled to write a satisfying conclusion, leaving it open for a third film.[72] This draft established Luke's sister as a new character undertaking a similar journey,[73] Vader's castle and his fear of the emperor,[74] distinct power levels in controlling the Force,[75] Yoda's unconventional speech pattern,[76] and bounty hunters, including Boba Fett. Lucas wrote Fett like the Man with No Name, combining him with an abandoned idea for a Super Stormtrooper.[77] Lucas's handwritten draft included mention of Vader being Luke's father, but the typed script omitted this revelation. Despite contradictory information in drafts that included the ghost of Luke's father, Lucas said he had always intended for Vader to be Luke's father and omitted it from scripts to avoid leaks.[17][78] Lucas included elements such as Han's debt to Jabba, and recontextualized Luke leaving Dagobah to rescue his friends: in Brackett's draft, Obi-Wan instructs Luke to leave; Lucas had Luke choose to do so. He also removed a scene of Luke massacring stormtroopers to convey him falling to the dark side, wanting to instead explore this in the next film.[70] Lucas believed it was important the characters be inspirational and appropriate for children.[79] His typed draft is titled Star Wars: Episode V The Empire Strikes Back.[76]

In June 1978, impressed with his work on Raiders of the Lost Ark, Lucas hired Lawrence Kasdan to refine the draft; Kasdan was paid $60,000.[17][61][80] In early July, Kasdan, Kershner and Lucas held a story conference to discuss Lucas's draft.[48][61] The group collaborated on ideas, challenging Lucas when his made no sense; Lucas embraced their input.[17][81] Mandated to deliver a fifth of the script every other week, Kasdan began his rewrite, focusing on developing character relationships and psychologies; he completed the third draft by early August.[82] This version refined Minch Yoda—alternately named "the Critter", Minch, Buffy, and simply Yoda—from a slimy creature to a small blue one; each version retained the character's long life and wisdom.[17][35] Yoda was intended to teach Luke to respect everyone and not judge by appearances, and defy audience expectations.[17] The draft tightened or expanded dialogue to better pace action scenes, added more romance, and added or changed locations, such as moving a Vader scene from a spaceship deck to his private cubicle.[83] Lucas removed a line mentioning Lando deliberately abandoning his people, and had Luke contact Leia through the Force instead of Obi-Wan's ghost.[84] The fourth draft—mostly the same but with more detailed action—was submitted on October 24.[85]

Although some of Brackett's ideas remained, such as Luke's Dagobah training, her dialogue and characterization were removed.[35][86] Kasdan described her take as from "a different era", lacking the necessary tone.[71] Kazanjian did not believe the Writers Guild of America West would approve of her receiving credit, but Lucas liked Brackett and supported her credit as co-writer. He also provided for her family beyond her contracted pay.[86][35] The fifth draft was completed in February 1979. It revised some scenes and introduced a "Hogmen" species devised by Kershner; Lucas did not like the idea because he perceived them as slaves.[87]

Casting

[edit]

Mark Hamill (Luke), Carrie Fisher (Leia), Harrison Ford (Han), Peter Mayhew (Chewbacca), and Kenny Baker (R2-D2) all reprised their Star Wars roles.[41][88] Hamill and Fisher were contracted for a second, third, and fourth film, but Ford had declined similar terms because of earlier bad experiences; he agreed to return because he wanted to improve on his Star Wars performance.[89] Hamill spent four months bodybuilding and learning karate, fencing, and kendo to prepare for his stunts.[87]

David Prowse hesitated to return as Darth Vader because, as he was hidden behind a costume, he believed the role offered little job security; he returned after being told further delays would lead to his being replaced.[90] James Earl Jones returned to voice Vader but, as with Star Wars, declined a credit because he considered himself "special effects" to Prowse's physical performance. He earned $15,000 for half a day's work, plus a small percentage of the profits.[91][92] Anthony Daniels was reluctant to return as C-3PO because he had received little acknowledgment for his previous performance, as the filmmakers played down his involvement to portray the droid as a real being. He ultimately agreed, however, for an improved salary.[93] Alec Guinness said he could not return as Obi-Wan because his failing eyesight required him to avoid bright lights.[56] Recasting him was considered but, determined to recruit him, Lucas agreed to a deal in late August 1979 which gave him a more limited role. Guinness was paid 0.25% of Empire's box office gross for his few hours of work.[94]

Billy Dee Williams was cast as Lando Calrissian, making him the first black actor with a starring role in the series.[88][95] He found the character interesting because of his cape and Armenian surname; Williams believed this gave him room to develop the character. Williams said Lando was much like himself—a "pretty cool guy".[10] He believed it was a token role, but was assured it was not specifically written for a black actor.[96] Kershner said Williams had the fantastic charm of a "Mississippi riverboat hustler".[96] Howard Rollins, Terry Alexander, Robert Christian, Thurman Scott, and Yaphet Kotto were also considered for the part.[85][97] Yoda was voiced and puppeteered by Frank Oz, with assistance from Kathryn Mullen, David Barclay, and Wendy Froud.[98] Lucas had intended for a different actor to provide Yoda's voice, but decided it would be too difficult to cast someone who could match their voice to Oz's puppetry.[27]

Jeremy Bulloch did not audition for Boba Fett; he was hired because the costume fit him. It was uncomfortable and top-heavy, making it difficult to maintain his balance, and the mask often steamed up. Bulloch assumed his lines would be dubbed over, as he had little dialogue (Fett's voice actor, Jason Wingreen, remained uncredited until 2000).[99] Bulloch also appears as an Imperial officer who restrains Leia on Bespin. No other cast member was available for this role, so Kurtz had him quickly change out of the Fett costume to stand in. John Morton portrays Fett in the same scene.[g] There was no extensive casting for the Emperor. Lucas chose Clive Revill to provide the character's voice, and actress Marjorie Eaton physically portrayed the Emperor in test footage. The footage proved unsatisfactory, and special effects artist Rick Baker created a full mask that his wife Elaine wore. Chimpanzee eyes were superimposed over her face; cat eyes and assistant accountant Laura Crockett's eyes were also considered.[26][27][59]

Pre-production

[edit]Pre-production began in early 1978. Although Kershner wanted two years, this phase only lasted a year.[100] Seeking an area to represent the ice planet Hoth, location scouts considered Finland, Sweden, and the Arctic Circle. The location needed to be free of trees and near populated areas for amenities.[101] Kershner credited a Fox distribution employee with recommending Finse, Norway; Kurtz said it was Reynolds who had done so.[101] For the bog planet Dagobah, scouts looked at Central Africa, Kenya, and Scandinavia, but Lucas wanted to avoid shooting on location. He funded the construction of a "Star Wars stage" at Elstree Studios, London, for the Dagobah and rebel base sets. Construction for the stage—which measured 1,250,000 cubic feet (35,000 m3) and cost $2 million—began at the end of August.[41][102] Sets were the single biggest expense of the production, costing a total of $3.5 million. By December, the budget had increased to $21.5 million, more than double the original estimate.[103] Financial projections for The Chapter II Company suggested it would run a monthly deficit of $5–25 million by the end of 1979, including over $2 million in production costs and $400,000 to fund ILM.[85]

As the start of filming in January 1979 loomed, a fire on Elstree's Stage 3—where The Shining (1980) was being filmed—destroyed the space planned for Empire's sets.[65][104] The impact was significant, resulting in the Empire production being forced to give up two stages so The Shining could continue filming. Sixty-four sets had to be moved through nine stages and the filming schedule had to be altered. Poor weather delayed construction of necessary sets, props, and the Star Wars stage.[104] By February 25, the Finse location crew had arrived in Norway to receive flown-in equipment containers and begin digging trenches for battle scenes.[105]

Music

[edit]The musical score for The Empire Strikes Back was composed and conducted by John Williams and performed by the London Symphony Orchestra, at a cost of about $250,000.[106] Williams began planning the score in November 1979, estimating the film would require 107 minutes of music.[107] For two weeks across 18 three-hour sessions just after Christmas, Williams recorded the score at Anvil Studios and Abbey Road Studios, London.[108] Up to 104 musicians were involved at a time, playing such instruments as oboes, piccolos, pianos, and harps.[109]

Filming

[edit]Commencement in Norway

[edit]

Principal photography began on March 5, 1979, on the Hardangerjøkulen glacier near Finse, Norway, representing the planet Hoth.[h] Initially scheduled to conclude on June 22, by the end of the first week it was obvious it would take longer and cost more.[41][112]

Filming the Hoth scenes on a set was considered, but ultimately rejected as inauthentic. The location filming coincided with the area's worst snowstorm in half a century, impeding the production with blizzards, 40-mile-per-hour (64 km/h) winds, and temperatures between −26 °F (−32 °C) and −38 °F (−39 °C).[i] The weather cleared only twice; some days, filming could not take place.[115] The frigid conditions made the acetate film brittle, camera lenses iced over, snow seeped into equipment, and effects paint froze inside the tin.[17][116] To counter these effects, lenses were kept cool but the camera body was warmed to protect the film, battery, and camera operators' hands.[117] The crew was outside for up to 11 hours at a time, being subjected to thin air, limited visibility, and mild frostbite; one crewman slipped and broke two ribs.[118] The difficult conditions led to strong camaraderie among crewmembers.[119]

Avalanches blocked direct transport links, and trenches dug by the crew quickly filled with snow. Scenes could be prepared only a few hours in advance and many scenes were filmed just outside the crew's hotel as the shifting weather regularly altered the scenery.[17][120] Although Fisher was not scheduled to film scenes in Norway, she joined Hamill on location because she wanted to observe the process.[87] Ford was not scheduled for the Finse phase, but to compensate for the delays, he was brought there instead of creating a separate set in a Leeds studio. On a few hours' notice, he arrived in Finse, having traveled the last 23 miles (37 km) of the snow-laden journey by snowplow.[121] Production returned to England after a week, though Hamill had an additional day of filming. The second unit remained in Norway through March to film explosions, incidental footage, and battle scenes featuring 35 mountain rescue skiers as extras. The skiers' work was compensated with a donation to the Norwegian Red Cross.[122]

To film the Imperial probe landing, eight sticks of dynamite were placed on the glacier and set to explode at sunrise, but the demolitions expert in charge knocked the battery out of his radio and received the message too late to capture the intended shot.[123] The opening sweeping shot of the area was captured by flying a helicopter to 15,000 feet (4,600 m) and performing a controlled drop at a rate of 30 miles per hour (48 km/h) or 2,500 feet (760 m) a minute.[124] A heated shelter for the helicopter had to be constructed, which delayed filming of the shot by four weeks.[125] The second unit, scheduled to be in Finse for three weeks, was there for eight.[124] When the crew returned to London, they had only half the planned footage, and background images for special effects shots were uneven.[17][114][126] Empire's budget increased to around $22 million because of the delays and having to rework scenes to compensate for the missing footage.[127]

Filming at Elstree Studios

[edit]

Filming at Elstree began on March 13, 1979.[127] Production remained behind schedule without Stage 3 (which had been destroyed by fire), and the incomplete Star Wars stage lacked protection from the cold weather. The result was that the crew had to work out of any available space.[128] To save time, some scenes were shot simultaneously, such as those set in the ice cavern and medical bay.[129] Kershner wanted each character to make a unique entrance in the film. While filming Vader's entrance, the snow troopers preceding Prowse tripped over the polystyrene ice, and the stuntman behind him stood on his cape, breaking it off, causing Prowse to fall onto the snow troopers.[130]

The shoot was strenuous and mired in conflicts.[17][131] Fisher suffered from influenza and bronchitis, her weight dropped to 85 pounds (39 kg) while working 12-hour days, and she collapsed on set from an allergic reaction to steam or spray paint. She was also allergic to most makeup.[132] Her overuse of hallucinogens and painkillers worsened her condition, as did the anxiety she experienced while performing her speech to the rebels.[133] Stress and personal traumas led to frequent arguments among Hamill, Fisher, and Ford.[17][134] Ford and Hamill fell ill or were injured at different times.[135] Hamill was depressed by his isolation from human cast members, as his scenes required him to interact mostly with puppets, robots, and actors whose voices would be added later or dubbed over.[136][137] He was meant to use an earpiece to hear Oz's Yoda dialogue, but for various reasons this did not work, and he struggled to form a relationship with the character. The Dagobah set was liberally sprayed with mineral oil, which caused him physical discomfort for long periods. Hamill called it a "physical ordeal the whole time ... but I don't really mind that".[136] At one point, Oz cheered Hamill up with a Miss Piggy routine. Hamill recalled Ford giving him a kiss instead of reading his lines, which entertained the crew.[59] Mayhew fell ill while filming Han's torture scene because the set used bursts of steam, which raised the ambient temperature to 90 °F (32 °C) while he was wearing a wool suit.[138]

Bank of America representatives visited the set in late March, concerned about rising costs.[139] Lucas rarely visited the set, but arrived on May 6 after realizing the production was behind schedule and over budget.[41] An official Lucasfilm memo instructed staff to misstate the film's direct costs as $17 million.[140] At this point, Kurtz and Lucas estimated it would cost $25–28 million to complete filming.[127][140] Finances ran out in mid-July when Bank of America refused to increase the loan.[17][141] The crisis was kept from the crew, including Kershner, and tactics were used to delay its impact, including paying staff biweekly instead of weekly and Lucas borrowing money from his merchandising company Black Falcon.[141] Lucas worried he would have to sell Empire and its associated rights to Fox to sustain the project, losing his creative freedom. Fox was also threatening to buy out the bond and take over filming.[127][141] With about 20% of Empire left to film, Lucasfilm president Charles Weber arranged for Bank of Boston to refinance the loan to $31 million, including $27.7 million from Bank of Boston and $3 million guaranteed by Fox in exchange for an increased percentage of the theatrical returns and 10% of merchandising profits. Lucasfilm took out the loan, making the company directly liable.[17][127][142]

The Star Wars stage was completed in early May. It was too small to house the Rebel hangar and Dagobah sets, and an extension had to be funded and built. The producers mandated filming begin on the stage on May 18, regardless of its state.[143] The hangar scene involved 77 rebel extras, which cost £2,000 per day.[144] Around 50 short tons (45 long tons) of dendritic salt, mixed with magnesium sulfate for a sparkle effect, were used for the snowy sets; this combination of substances gave the cast and crew headaches.[145] Second unit director John Barry died suddenly in early June; Harley Cokeliss replaced him a week later.[65][146][147] The typical purpose of the second unit was to do time-consuming filming for special effects shots, but they were now filming main scenes—including Luke's ice cave imprisonment—because the schedule had overrun by around 26 days.[148] Hamill was unavailable for several days after injuring his hand during a stunt jump from a speeder bike. Having been called in for the stunt the same day his son was born, aggravated by the salt-laden setting, and exhausted, he angrily chastised Kurtz for not using a double for the scene.[149] Kershner's hands-on directing style, which included him acting out how he wanted a scene performed, agitated Hamill; Kershner, for his part, was frustrated that Hamill was not following his advice.[150]

The life-size hangar set was dismantled in mid-June to allow the construction of other sets around the full-scale Millenium Falcon. These scenes had to be filmed efficiently, so the Falcon could be dismantled to make way for the Dagobah set.[151] Filming began on the carbon chamber scene in late June while the second unit filmed anything they could.[152] The raised set was largely incomplete, and low lighting and steam were used to conceal any obvious flaws. The fog machines and heat from the steam made many cast and crew members sick; it took approximately three weeks to film.[153] The confession of love between Leia and Han was scripted with both of them admitting their feelings for the other. Kershner felt this was too "sappy". He had Ford improvise lines repeatedly until Ford said he would do only one more take; his response to Leia's confession of love in the final take was "I know".[17] By the end of the month, cast and crew morale was low.[154]

The duel, Dagobah, and conclusion

[edit]Hamill returned in early July to film his climactic battle against Darth Vader, portrayed by stunt double Bob Anderson, who said the experience was like fighting blindfolded because of the costume. Hamill spent weeks practicing his fencing routine, eventually growing frustrated and refusing to continue.[155] The next scene, where Vader confesses he is Luke's father, was shrouded in secrecy. Prowse was given the line "Obi-Wan Kenobi is your father" to read because he was known for repeatedly leaking information.[17] Only Kershner, the producers, and Hamill knew the actual line.[17][156] While filming the scene, Hamill was positioned on a platform suspended 35 feet (11 m) above a pile of mattresses.[17] Footage of his fall into the reactor shaft was damaged during processing and the scene had to be reshot in early August.[157] The Vader confrontation took eight weeks to film. Hamill insisted on doing as many of his stunts as possible, though the insurers refused to allow him to perform a 15-foot (4.6 m) fall out of a window. He accidentally fell from a nine-inch ledge 40 feet (12 m) high but rolled on landing to avoid injury.[136] Lucas returned to the set on July 15 and stayed for the rest of filming.[141] He rewrote Luke's scenes on Dagobah, removing or trimming them so they could be shot in just over two weeks.[158]

Most of the cast completed filming by the start of August, including Ford, Fisher, Williams, Mayhew, and Daniels.[159] Hamill began filming on the Dagobah set with Yoda. They only had 12 days to film because Oz was scheduled for another project.[160] With the film now over 50 days behind schedule, Kurtz was removed from his role and replaced by Kazanjian and associate producer Robert Watts.[161] One of the last scenes shot was of Luke exploring the dark side tree on Dagobah. A wrap party was held on the set to mark the official conclusion of filming on September 5, 1979, after 133 days. Guinness filmed his scenes against a bluescreen the same day.[162][163] Kershner and the second unit continued filming additional footage, including Luke's X-Wing being raised from the swamp.[162] Kershner left the set on September 9, and Hamill finished 103 days of filming two days later.[127][164] The second unit finished filming on September 24 with Hamill's stunt double.[165][166] There was approximately 400,000 feet (120,000 m) of film, or 80 hours of footage.[167]

The final budget was $30.5 million.[168][vi] Kurtz blamed inflation, which had increased resource, cast, and crew costs significantly.[169] Lucas blamed Kurtz for lack of oversight and poor financial planning.[17][170] Watts said Kurtz was not good with people and never developed a working relationship with Kershner, making it difficult for him to temper the director's indulgences.[171] Kurtz had also given Kershner more leeway because of the delays caused by the Stage 3 fire.[140] Kershner's slower work pace had frustrated Lucas.[17][172] He described his filming style as frugal, performing two or three takes with little coverage film that could later compensate for mistakes. Watts and Reynolds said Kershner often looked at new ways of doing things, but this required planning that only delayed things further.[135] Kershner had tried replicating the quick pacing of Star Wars, not lingering on any scene for too long, and encouraged improvisation, modifying scenes and dialogue to focus more on characters' emotions, such as C-3PO interrupting Han and Leia as they are about to kiss.[17][173][174] Kazanjian said many mistakes were made but blamed Weber, Lucasfilm vice president John Moohr, and primarily Kurtz.[175] Actor John Morton called Kurtz an unsung hero, who brought his experience of filming war to Empire.[176]

Post-production

[edit]The schedule overrun resulted in filming and post-production taking place simultaneously; filmed footage was shipped immediately to ILM to begin effects work.[177] A rough cut resembling the finished film (minus special effects) was put together by mid-October 1979.[178] Lucas provided 31 pages of notes about changes he wanted, mainly alterations in dialogue and scene lengths.[179] Jones recorded Vader's dialogue in late 1979 and early 1980.[180] In early 1980, Lucas changed the long-planned opening of Luke riding his tauntaun to a shot of the Star Destroyer launching probes. He continued tweaking elements to improve the special effects, but even with ILM staff working up to 24 hours a day, six days a week, there was not enough time to do everything they wanted.[181] A Dagobah pick-up scene, in which R2-D2 is spat out by a monster, was filmed in Lucas's swimming pool;[182] the Emperor's scenes were filmed in February 1980.[27]

Fox executives did not see a cut of the film until March.[183] That month, Lucas decided he wanted an additional Hoth scene and auditioned 50 ILM crew to appear as Rebels.[27] The final 124-minute cut was completed on April 16, which triggered a $10 million payment from Fox to Bank of Boston.[183][184][185] Lucasfilm also launched an employee bonus scheme to share Empire's profits with its staff.[186] Test screenings were held in San Francisco on April 19. While the tauntaun special effect was criticized, audiences liked Han's reply of "I know" to Leia's confession of love. Lucas was unimpressed by the scene, believing it was not how Han would act.[17][187] Because the magnetic soundtrack could flake from the film reels, Kurtz hired people to watch the film reels 24 hours a day to identify defects; 22% were defective.[168]

Shortly after the film's theatrical release, Lucas decided the ending was unclear about where Luke and Leia were in relation to Lando and Chewbacca. In the three-week window between its limited and wider release, Lucas, Johnston, and visual effects artist Ken Ralston filmed enhancement scenes at ILM, using existing footage, a new score, modified dialogue, and new miniatures to create establishing shots of the Rebel fleet and their relative positions.[188] By the project's conclusion, around 700 people had worked on Empire.[189]

Special effects and design

[edit]Lucas's firm, Industrial Light & Magic, developed the special effects for The Empire Strikes Back at a cost of $8 million, including staffing and the construction of the company's new facility in Marin County, California.[168] The building was still under construction when staff arrived in September 1978, and initially lacked the equipment that would be necessary to complete their work.[111][114][190] Compared to the 360 special effects shots for Star Wars, Empire required around 600.[191]

The crew, supervised by Richard Edlund and Brian Johnson, included Dennis Muren, Bruce Nicholson, Lorne Peterson, Steve Gawley, Phil Tippett,[111] Tom St. Amand,[192] and Nilo Rodis-Jamero.[190] Up to 100 people worked on the project daily, including Stuart Freeborn, who was responsible mainly for crafting the Yoda puppet.[57][193] Various techniques, including miniatures, matte paintings, stop motion, articulated models and full-size vehicles were used to create Empire's many effects.[65][134][194]

Release

[edit]Context

[edit]

Industry professionals expected comedies and positive entertainment to dominate theaters in 1980 because of low morale in the United States caused by an economic recession. This generally increased theatrical visits as audiences sought escapism and ignored romantic films and depictions of blue-collar life.[195][196] A surge of interest in science fiction following Star Wars led to many low-budget entries in the genre attempting to profit by association and big-budget entries such as Star Trek: The Motion Picture and The Black Hole, both released just months before The Empire Strikes Back.[41] Sequels were not expected to perform as well as their originals, and there were low expectations for merchandising.[197] Even so, tie-in deals were arranged with Coca-Cola, Nestlé, General Mills, and Topps collectibles.[198]

Fox was confident in the film and spent little money on advertising, taking out small advertisements in newspapers instead of full-page spreads.[184] The studio's market research showed 60% of those interested in the film were male.[199] Lucasfilm set up a telephone number allowing callers to hear a message from cast members.[200] Fox demanded a minimum 28-week appearance in theaters, although 12 weeks was the norm for major films.[186] Estimates suggested Empire needed to earn $57.2 million to be profitable, after marketing, distribution, and loan interest costs.[201]

Credits and title

[edit]As with Star Wars, Lucas wanted to place all of the crew credits at the end of the film to avoid interfering with the opening. The Writers Guild of America (WGA) and Directors Guild of America (DGA) had allowed this for the first film because Lucas directed and it opened with the logo for his namesake Lucasfilm, but for Empire they refused to allow Kershner or the first and second unit directors to be credited only at the end, fined Lucas $250,000 when he ignored them and tried to have the film removed from theaters.[173] Because Lucas had followed the laws relevant to the United Kingdom where it was produced, the DGA was unable to sanction him and instead fined Kershner $25,000.[199] Lucas paid his fine but was so frustrated that he left the WGA, DGA, and Motion Picture Association, which restricted his ability to write and direct future films.[173][202]

The Hollywood Reporter leaked the film's title in January 1978[203]; it was officially announced in August.[204] The opening crawl identified the film as Star Wars: Episode V — The Empire Strikes Back, establishing Lucas's plan to make a nine-part Star Wars series. Star Wars was also renamed Episode IV — A New Hope.[205][206] Roger Kastel designed the theatrical poster.[207]

Box office

[edit]

A sneak preview of The Empire Strikes Back took place on May 6, 1980 at the Dominion Theatre in London, followed by another preview screening on May 17 at the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C.[208] This event, which featured the principal cast, was attended by 600 children, including Special Olympians.[209][208] The film's world premiere took place on May 20 at the Odeon Leicester Square in London. Dubbed "Empire Day", the event included actors in Stormtrooper attire interacting with people across the city.[210][211][208]

In North America, Empire opened mid-week on May 21, leading into the extended Memorial Day holiday weekend.[212] The number of theaters was deliberately limited to 126 to make it difficult to get a ticket, thus generating more appeal—a strategy used with films expected to receive positive word of mouth.[184] The film earned $1.3 million during its opening day—an average of $10,581 per theater.[213] It garnered a further $4.9 million during the weekend and $1.5 million during the Monday holiday, for a total of $6.4 million—an average of $50,919 per theater. This made Empire the number one film of the weekend, ahead of the counterprogrammed debuts of the comedy The Gong Show Movie ($1.5 million) and The Shining ($600,000).[212][214][215] By the end of its first week, the film had earned $9.6 million—a 60% increase over Star Wars—averaging $76,201 per theater, the highest-ever figure for a film in over 100 theaters.[184][216][217]

It remained number one until its fourth weekend, when it fell to third with $3.6 million, behind the spoof comedy Wholly Moses! ($3.62 million) and the Western Bronco Billy ($3.7 million).[213][218] It regained the number one position in its fifth weekend, expanding its theater count to 823 and earning $10.8 million.[213][219] Combined with its weekday gross, Empire garnered a single-week gross of approximately $20 million, a box office record the film would hold until Superman II's $24 million the following year.[220][221][222] It remained number one for the next seven weeks, before falling to number two in its thirteenth week with $4.3 million, behind the debuting Smokey and the Bandit II ($10.9 million). Detailed box office tracking is unavailable for the rest of Empire's 32-week, 1,278-theater total run.[213][223]

Empire earned between $181.4–209.4 million in its initial North American release, making it the highest-grossing film of the year, ahead of the comedy films 9 to 5 ($103.3 million), Stir Crazy ($101.3 million), and Airplane! ($83.5 million).[195][224][225] Although it earned less than the $221.3 million of Star Wars, Empire was considered a financial success. Industry experts estimated the film returned $120 million to the filmmakers,[172][195][225] which recouped Lucas's investment and cleared his debt;[226] he paid out $5 million in employee bonuses.[173] Box office figures are unavailable for all the releases outside of North America in 1980, although The New York Times reported the film performed well in the United Kingdom and Japan. According to Variety, Empire earned approximately $192.1 million, giving the film a cumulative worldwide gross of $401.5 million, making it the highest-grossing film of the year.[1][2][3][vii] Empire did not achieve the same success as Star Wars, which Lucas blamed on its inconclusive ending.[172][227]

Empire has received multiple theatrical re-releases, including in July 1981 ($26.8 million), November 1982 ($14.5 million), and Special Edition versions (modified by Lucas) in February 1997 ($67.6 million).[228] Cumulatively, these releases have raised the North American box office gross to $290.3–$292.4 million.[j] It is estimated to have earned a worldwide total of $538.4–$549 million.[4][5] Adjusted for inflation, the North American box office is equivalent to $920.8 million, making it the thirteenth-highest-grossing film ever.[230]

Reception

[edit]Critical response

[edit]The Empire Strikes Back received mixed reviews upon its initial release, a change from the positive reception of Star Wars.[172][231][232] In March 1981, The Los Angeles Times released a summary of the leading critics’ choices for top 10 films of the year: Robert Redford’s Ordinary People appeared on 42 lists, while Empire made it onto 24.[233] Fan reactions were decidedly mixed, with many concerned by the film's change in tone and surprising narrative revelations, particularly Leia's love for Han over Luke and Luke's relationship with Vader.[234][235] Even so, the 536 audience members polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A+" on an A+ to F scale, with males and those under the age of 25 rating it highest.[236]

Some critics believed The Empire Strikes Back was a good film but not as enjoyable as Star Wars.[237][238][239] They believed the tonal shift featuring darker material and more mature story lines detracted from the charm, fun, and comic silliness of the original.[237][239][240] The Wall Street Journal's Joy Gould Boyum believed it was "absurd" to add dramatic weight to the lighthearted Star Wars, stripping it of its innocence. Writing for The Washington Post, Gary Arnold found the darker undercurrents and greater narrative scale interesting because it created more dramatic threads to explore.[241][239] The New Yorker's David Denby argued it was more spectacular than the original, but lacked its camp style.[240] The Hollywood Reporter's Arthur Knight believed the novelty of the original and the plethora of space opera films produced since made Empire seem derivative; even so, he called it the best in the genre since Star Wars.[238][241] Writing for Time, Gerald Clarke said Empire surpassed Star Wars in several ways, including being more visually and artistically interesting.[242] The New York Times's Vincent Canby called it a more mechanical, less suspenseful experience.[237]

Writing for the Los Angeles Times, Charles Champlin said the inconclusive ending cleverly completed the narrative while serving as a cliffhanger, but Clarke called it a "not very satisfying" conclusion.[243][244] Canby and the Chicago Reader's Dave Kehr believed that as the middle film, it should have focused on narrative development instead of exposition, finding little narrative progression between the film's beginning and end.[237][245][239] The Washington Post's Judith Martin labeled it a "good junk" film, enjoyable but fleeting, because it lacked a stand-alone narrative.[246] Knight and Clarke found the story sometimes difficult to follow—Knight because the third act jumped between separate storylines, and Clarke because he missed important information in the fast-paced plot.[238][244] Kehr and Sight & Sound's Richard Combs wrote that characterization seemed to be less important than special effects, visual spectacle and action set pieces that accomplished little narratively.[245][247]

Reviews were mixed for the principal cast.[239][243][245] Knight wrote that Kershner's direction made the characters more human and less archetypal.[238] Hamill, Fisher, and Ford received some praise, with Champlin calling Hamill "youthfully innocent" and engaging, and Fisher independent.[238][243][248] Arnold described the character progression as less about development and more about "finesse", with little change taking place,[241] while Kehr felt the characters were "stiffer" without Lucas's direction.[245] Knight called Guinness's performance half-hearted,[238] and Janet Maslin criticized Lando Calrissian, the only major black character in the film, as "exaggeratedly unctuous, untrustworthy and loaded with jive".[249] The Chicago Tribune's Gene Siskel said the non-human characters, including the robots and Chewbacca, remained the most lovable creatures, with Yoda being the film's highlight.[250] Knight, Gould Boyum, and Arnold thought Yoda to be incredibly lifelike; Arnold considered his expressions so realistic that he believed an actor's face had been composited onto the puppet.[238][239][241] Canby called the human cast bland and nondescript, and said even the robot characters offered diminishing enjoyment, but Yoda was a success when used sparingly.[237]

Although Arnold praised Kershner's direction, others believed that Lucas's oversight was obvious and Empire lacked Kershner's established directorial sensibilities. Denby described his work as "impersonal" and Canby believed it was impossible to identify what Kershner had contributed.[237][240][241] Combs believed Kershner was an "ill-advised" director because he emphasized the characters, and the result was common tropes at the expense of the comic-strip pace of Star Wars.[247] Peter Suschitzky's cinematography was praised for its visuals and bold color choices,[238][241] and the special effects were lauded as "breathtaking",[239] "ingenious",[238] and visually dazzling.[241] Jim Harwood said he was let down only by the familiarity of the effects from the original, which were emulated by other films.[248] Champlin appreciated that the effects were used to enhance scenes rather than being the focus.[243]

Accolades

[edit]

At the 1981 Academy Awards, The Empire Strikes Back won the award for Best Sound (Bill Varney, Steve Maslow, Gregg Landaker, and Peter Sutton) and a Special Achievement Academy Award for Best Visual Effects (Johnson, Edlund, Muren, and Nicholson). The film received a further two nominations: Best Art Direction (Reynolds, Leslie Dilley, Harry Lange, Alan Tomkins, and Michael Ford) and Best Original Score (John Williams).[251] Williams also won two Grammy Awards: Best Instrumental Composition and Best Score Soundtrack for Visual Media.[252] He earned the film's sole Golden Globe Awards nomination, for Best Original Score.[253]

The 34th British Academy Film Awards garnered Empire one award for Best Music (Williams), and two additional nominations: Best Sound (Sutton, Varney, and Ben Burtt) and Best Production Design (Reynolds).[254] At the 8th Saturn Awards, Empire received four awards: Best Science Fiction Film, Best Director (Kershner), Best Actor (Hamill), and Best Special Effects (Johnson and Edlund).[255] The film also won a Hugo Award for Best Dramatic Presentation and a People's Choice Award for Favorite Motion Picture.[256][257]

Post-release

[edit]Special Edition and other changes

[edit]As part of his plan to develop a prequel trilogy of films in the late 1990s, Lucas remastered and rereleased the original trilogy, including Empire, under the title Star Wars Trilogy: Special Edition to test special effects. This included altering scenes or adding new scenes, some of which tied into the prequel films. Lucas described it as bringing the trilogy closer to his original vision with modern technology. Among the alterations were full shots of the wampa and computer-generated locations with added buildings or people.[258] These editions were well received by critics. Roger Ebert called Empire the best and "heart" of the original trilogy.[259][260][261]

Since their initial release, the Special Editions have been altered multiple times. For the 2004 rerelease, the Clive Revill/Elaine Baker Emperor was replaced by Ian McDiarmid, who had performed the role since Return of the Jedi (1983).[258] Temuera Morrison, who portrayed Fett's clone predecessor in Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones (2002), dubbed over Wingreen's lines.[99] Minor changes were made for the 2011 Blu-ray release, including adding flames to the probe droid's impact crater and color modifications.[262][263] The Special Edition releases were controversial with fans, who considered the changes to the original films unnecessary or too substantial.[258][264] The unaltered versions have been commercially unavailable since a 2006 DVD release, which used unrestored footage from an early 1990s Laserdisc release. Harmy's Despecialized Edition is an unofficial fan effort to preserve the unaltered films.[265][266] The 2010 documentary The People vs. George Lucas documents the relationship between the films, their fans, and Lucas.[267]

Home media

[edit]Empire was released on VHS (Video Home System), Laserdisc, and CED videodisc formats at Christmas 1984 at a price of $79.95 and became the top-selling tape at that price point at the time with sales of 375,000 units.[268] The VHS and Laserdisc versions received various releases in the following years, often alongside the other original trilogy films in collections, with minor alterations such as widescreen formats or remastered sound. The 1992 Special Collector's Edition included the documentary From Star Wars to Jedi: The Making of a Saga. In 1997, the Special Edition of the original trilogy was released on VHS.[269][270] When the film debuted on television in November 1987, it was preceded by a second-person introduction by Darth Vader, framed as an interruption of the Earth broadcast by the Galactic Empire.[271][272]

The film was released on DVD in 2004, collected with Star Wars and Return of the Jedi, with additional alterations to each film. The release included the documentary Empire of Dreams: The Story of the Star Wars Trilogy, about the making of the original trilogy.[273] Lucas said the modified versions were the way he had wanted them to be, and he had no interest in restoring the original theatrical cuts for release. Public demand eventually led to the release of the 2006 Limited Edition DVD collection that included the original unmodified films transferred from the 1993 Laserdisc Definitive Edition, creating problems with the image display.[269]

Empire was released on Blu-ray in 2011, as part of a collection containing the Special Edition original trilogy and a separate version containing the original and prequel trilogies alongside featurettes about the making of the films.[262][274][275] In 2015, Empire and the other available films were released digitally on various platforms. A 4K resolution version—restored from the 1997 Special Edition print—was released in 2019 on Disney+.[276][277] In 2020, a 27-disc Skywalker Saga box set was released, which contained all nine films in the series. It featured a Blu-ray version and a 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray version of each film, as well as special features from the 2011 release.[278]

Other media

[edit]Merchandise for The Empire Strikes Back includes posters, children's books, clothing, character busts and statues, action figures, furnishings, and Lego sets.[k] The novelization of the film, written by Donald F. Glut and released in April 1980, was a success, selling 2–3 million copies.[283][284] A Star Wars comic book series, launched in 1977 by Marvel Comics and written by Archie Goodwin and Carmine Infantino, adapted the original trilogy of films; Empire's run began in 1980.[285][286] The book The Making of the Empire Strikes Back (2010) by J. W. Rinzler provides a comprehensive history of the film's production, including behind-the-scenes photos and cast interviews.[282][287]

The film was the first in the series to be adapted for video games, beginning with Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1982) developed by Parker Brothers for the Atari 2600 games console.[288][289] This was followed in 1985 by the Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back arcade game.[290] Star Wars Trilogy Arcade (1998) features the Hoth battle as a level.[290] Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back was released in 1992 for the Nintendo Entertainment System and Game Boy, and Super Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back followed in 1993 for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.[289] Scenes from Empire have also appeared in games like Star Wars: Rogue Squadron (1998) and Star Wars Battlefront: Renegade Squadron (2007).[289][291] The Empire Strikes Back pinball machine (1980) was the first officially licensed Star Wars pinball machine. It became a collector's item, as only 350 machines were produced exclusively in Australia.[290]

Thematic analysis

[edit]Mythology and inspirations

[edit]Critical analysis has suggested various inspirations for Empire, particularly the early 1930s Flash Gordon serials that include a cloud city similar to Bespin. Film critic Tim Robey wrote that much of Empire's imagery and narrative can be connected to the 1975 film Dersu Uzala, directed by Akira Kurosawa—whose work inspired Lucas.[292][293] Muren described the Empire's assault on Hoth with AT-AT vehicles as an analogy for the Vietnam War, specifically an invading military employing equipment inappropriate for the local terrain.[294]

Clarke identified Luke as the heir to mythological heroes, such as Prometheus, Jason, and Galahad. He is guided initially by a traditional aide, Obi-Wan, who offers the promise of destiny until he is replaced by Yoda.[295] Anne Lancashire wrote that the Yoda narrative is a traditional mythological tale in which the hero is trained by a wise old master and must abandon all his preconceived notions.[296] Clarke described Luke's journey as the hero who ventures into the unknown to be tested by his own dark impulses but eventually overcomes them. He believed this represented the human ability to control irrational impulsiveness to serve love, order, and justice.[295]

Lucas wanted Yoda to be a traditional fairy-tale or mythological character, akin to a frog or an unassuming old man, to instill a message about respecting everyone and not judging on appearance alone, because he believed that would lead the hero to succeed.[297] The New York Observer's Brandon Katz described Yoda as deepening the Force through philosophy. Yoda says they are all luminous beings beyond just flesh and matter, and presents the Jedi as Zen warriors who work in harmony with the Force. Kasdan described them as enlightened warrior priests, similar to Samurai.[283][297]

Religion

[edit]In developing the Force, Lucas said he wanted it to represent the core essence of multiple religions unified by their common traits. Primarily, he designed it with the intent that there is good, evil, and a god. Lucas's personal faith includes a belief in God and basic morality, such as treating others fairly and not taking another's life. The Presbyterian Journal described the film's religious message as closer to Eastern religions such as Zoroastrianism or Buddhism than Judeo-Christian, presenting good and evil as abstract concepts. Similarly, God or the Force is an impersonal entity, taking no direct action. Christianity Today said that the film's drama is caused by the absence of a righteous god or being creating a direct influence.[283]

Lancashire and J. W. Rinzler described Luke's journey as based purely on Christianity, focused on destiny and free will, with Luke serving as a Christ-like figure and Vader as a fallen angel attempting to lure him toward evil.[298][283] Kershner said any religious symbolism was unintentional, as he wanted to focus on the power of an individual's untapped potential instead of magic.[283]

Duality and evil

[edit]Anne Lancashire contrasted the first Star Wars film's message of idealism, heroics, and friendship with the more complex tone of Empire.[299] The latter challenges the former's notions, primarily because Luke loses his innocence in coming to perceive people as neither entirely good nor evil.[300][301] The scene in which Luke enters the dark side cave on Dagobah represents where his anger will lead him and forces him to move beyond his belief that he is completely on the light side of the Force.[295][296] Kershner said the cave tests Luke against his greatest fear, but because the fear is in his mind, and he brought his weapon with him, it creates a scenario where he is forced to use it.[302] After defeating the avatar of Vader, the mask splits open to reveal Luke's face, suggesting he will succumb to the temptations of the dark side unless he learns patience and to abandon his anger.[303]

The darkness is similarly presented in Han, a self-interested smuggler struggling with his growing feelings for Leia and the responsibility associated with her cause. The film represents his two sides in Leia and Lando, a representative of his smuggler life.[304] Empire questions the cost of friendship. Where Star Wars presents traditional friendship, Empire presents friendship as requiring sacrifice. Han sacrifices himself in the frigid cold of Hoth to save Luke's life.[300][305] Similarly, Luke abandons his Jedi training, something he has longed for, to rescue his friends. This can be seen as a selfish choice, as he does so against Yoda and Obi-Wan's instructions, potentially sacrificing himself for his friends instead of training to defeat the Empire, a cause his friends support.[300][305] According to Lancashire, characters are shown to be heroic through sacrificing for others instead of fighting battles.[306]

Lancashire believed that Luke's impatience to leave for Bespin exemplifies his lack of growth from his training.[303] There, Vader tempts him with the power of the dark side and the revelation that he is Luke's father.[283][295] Vader wants Luke's help to destroy the Emperor, not for good, but so that Vader can impose his own order over the galaxy.[283] This admission robs Luke of the idealized image of his Jedi father, reveals Obi-Wan's deception in hiding his parentage, and takes the last of his innocence.[300][307][308] Gerald Clarke suggests Luke is not strong or virtuous enough to resist Vader during this confrontation, and so allows himself to fall into the airshaft below, showing the antagonist does sometimes win.[295][300] The concept of a character having a good father and an evil father is a common story trope because of its simple representations of good and evil.[283] At the film's finale, Luke has a greater understanding of the relationship between good and evil, and the dual nature of people.[309]

Legacy

[edit]Critical reassessment

[edit]The Empire Strikes Back remains an enduringly popular piece of cinema.[176] It is considered groundbreaking for its cliffhanger ending, influence on mainstream films, and special effects.[l] Brian Lowry of CNN wrote that without the "groundwork laid by one of the best sequels ever, [the Star Wars franchise] wouldn't be the force that it is now".[314]

Despite the film's initial mixed reception, it has since been reevaluated by critics and fans and is now often considered the best film in the Star Wars series, and one of the greatest films ever made.[m] In 2014, members of the entertainment industry ranked Empire as the 32nd-best film of all time in a poll conducted by The Hollywood Reporter (Star Wars was #11).[325] Empire magazine named it the third-best film of all time, stating that the modern cliché of sequels employing a darker tone can be traced back to Empire.[317] A 1997 retrospective review by Roger Ebert declared the film the best of the original trilogy, praising the depth of its storytelling and its ability to create a sense of wonder in the audience.[326] A vote by 250,000 Business Insider readers in 2014 listed it as the greatest film ever made; it is also included in the 2013 film reference book 1001 Movies You Must See Before You Die.[327][328] The revelation that Vader is Luke's father continues to be seen as one of the greatest plot twists in cinema.[n] Similarly, Han saying "I know" in response to Leia's love confession is considered one of the most iconic scenes in the Star Wars films and one of the more famous lines of improvised dialogue in cinema.[o]

Empire magazine selected the film as the sixth greatest movie sequel, lauding the "bold" unresolved ending and willingness to avoid the same formula as the first film.[340] Den of Geek called it the second-best sequel—after Aliens (1986)—and hailed it as Lucas's "masterpiece".[315] Playboy named it the third-best sequel, describing the disclosure of the relationship between Luke and Vader as the "emotional core that has elevated Star Wars to the pantheon of timeless modern sagas".[316] The BBC and Collider listed it as one of the best sequels ever made,[341][342] while Time and Playboy described it as a sequel that surpasses the original.[316][343] Review aggregator Rotten Tomatoes recognizes it as the 27th-best sequel, based on review scores.[344] Rolling Stone's 2014 reader-voted list of the best sequels listed Empire at third.[345]

On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 95% of 112 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 9/10. The website's consensus reads: "Dark, sinister, but ultimately even more involving than A New Hope, The Empire Strikes Back defies viewer expectations and takes the series to heightened emotional levels."[346] Empire has a score of 82 out of 100 on Metacritic based on the reviews of 25 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[347] Characters introduced in the film, such as Yoda and Lando Calrissian, are now considered iconic.[p] The American Film Institute ranked Darth Vader as the third best villain on its 2003 list of the 100 Best Heroes & Villains, after Norman Bates and Hannibal Lecter.[353]

Cultural influence

[edit]The Empire Strikes Back was ubiquitous in American culture upon its release.[226] Freddie Mercury ended a 1980 Queen concert by riding on the shoulders of someone dressed as Darth Vader.[210][354][355] The film was referenced in political cartoons.[226] Kershner received letters from fans around the world asking for autographs, and from psychologists who had used Yoda to explain philosophical ideas to their patients.[334] Other films, television shows, and video games have extensively referenced or parodied the film,[356][357] including the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU),[358] Spaceballs, The Muppet Show, American Dad!, South Park,[356] The Simpsons,[359] Family Guy, and Robot Chicken.[360] In 2010, the United States Library of Congress selected The Empire Strikes Back for preservation in the National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[361][362]

Landon Palmer, Eric Diaz, and Darren Mooney argue that Empire, and not Star Wars, created the concept of the modern blockbuster film franchise, which includes sequels serving as chapters in an infinitely expanding narrative—a template which was embraced by other film properties in the decades following Empire's release. This new paradigm stood in opposition to the popular trend of exploiting a successful film by creating low-budget sequels (which resulted in diminishing returns, as happened with the Jaws franchise).[363][364][365] Instead, more money was spent on Empire to expand the fictional universe and reap greater box-office returns. The use of a cliffhanger ending to set up a future sequel is seen in many modern films, particularly those in the MCU.[363] It has also been suggested that Empire forged a narrative structure that continues to be emulated in trilogies, wherein the middle film is darker than the original and features an ending in which the protagonists fail to defeat the antagonists (which sets up a subsequent film). Emmet Asher-Perrin and Ben Sherlock cite the series Back to the Future, The Matrix, The Lord of the Rings, and Pirates of the Caribbean as examples.[366][367]

Filmmakers such as the Russo brothers, Roland Emmerich, and Kevin Feige, and actors such as Neil Patrick Harris and Jim Carrey, cite Empire as an inspiration in their careers or identify as fans.[q]

Sequels, prequels, and adaptations

[edit]The Empire Strikes Back was adapted into a 1982 radio play broadcast on National Public Radio in the United States.[373] Return of the Jedi was released in 1983, concluding the original film trilogy. Jedi's plot follows the Rebel assault on the Empire and Luke's final confrontation with Vader and the Emperor. Like the previous films, Jedi was a financial success and fared well with critics.[374][375]

Nearly two decades after the release of Empire, Lucas wrote and directed the prequel trilogy, consisting of The Phantom Menace (1999), Attack of the Clones (2002), and Revenge of the Sith (2005). The films chronicle the history between Obi-Wan Kenobi and Anakin Skywalker, and the latter's fall to the dark side and transformation into Darth Vader. The storylines and certain new characters in the prequel films polarized critics and fans.[r] After Lucas sold the Star Wars franchise to the Walt Disney Company in 2012, Disney developed a sequel trilogy, consisting of The Force Awakens (2015), The Last Jedi (2017), and The Rise of Skywalker (2019).[s] Original trilogy cast members—including Ford, Hamill, and Fisher—reprised their roles, and were joined by new characters portrayed by Daisy Ridley, John Boyega, Adam Driver, and Oscar Isaac.[385] Standalone films and television series have also been released, with narratives relating to the story arcs of the original trilogy.[t]

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ This figure represents the cumulative total accounting for the initial worldwide 1980 gross of $401.5 million and subsequent releases thereafter.[1][2][3][4][5]

- ^ Also known as Star Wars: Episode IV – A New Hope (1977)

- ^ As depicted in Star Wars, also known as Episode IV – A New Hope (1977).

- ^ As depicted in Return of the Jedi (1983)

- ^ Marjorie Eaton was filmed as the Emperor in February 1980, but her screen test was rejected. She was replaced by Elaine Baker in makeup with the voice provided by Clive Revill.[27]

- ^ The 1980 budget of $30.5 million is equivalent to $113 million in 2023.

- ^ The 1980 worldwide box office gross of $401.5 million is equivalent to $1.48 billion in 2023

Notes

[edit]- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[31][32][33][34]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:

[17][37][38] - ^ Attributed to multiple references:[40][17][37][41]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[41][17][42][43]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[17][35][60][61]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[64][35][65][67]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[99][19][28][21]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[110][88][41][111]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[88][113][114][17][41]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[228][229][4][5]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[279][280][281][282]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[310][311][312][313]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[315][316][317][318][319][320][176][321][322][323][67][324]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[329][320][330][321][331][332][333][310][334]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[335][336][337][338][339][320]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[348][349][297][350][351][352]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[368][369][370][371][372]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[267][376][377][378][379]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[380][381][382][383][384]

- ^ Attributed to multiple references:[18][386][387][388]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Groves 1997, p. 14.

- ^ a b Woods 1997, p. 14.

- ^ a b The New York Times, May 1980.

- ^ a b c "Star Wars: Episode V – The Empire Strikes Back". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 9, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ a b c "Star Wars Ep. V: The Empire Strikes Back". The Numbers. Archived from the original on June 29, 2021. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Ackerman, Spencer (February 13, 2012). "Inside the battle of Hoth: The Empire strikes out". Wired. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ "Star Wars: Han Solo origin film announced". BBC. July 8, 2015. Archived from the original on December 4, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ Epstein, Adam (July 8, 2015). "11 actors who are Harrison Ford-y enough to pull off a young Han Solo". Quartz. Archived from the original on November 5, 2021. Retrieved November 5, 2021.

- ^ Murphy, Mike (October 23, 2015). "We should think of Leia from Star Wars as a politician as much as a princess". Quartz. Archived from the original on October 25, 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ a b Moreau, Jordan (December 5, 2019). "Billy Dee Williams on getting back into Lando's cape for The Rise Of Skywalker". Variety. Archived from the original on April 8, 2020. Retrieved March 19, 2021.

- ^ MacGregor, Jeff (December 2017). "How Anthony Daniels gives C-3PO an unlikely dash of humanity". Smithsonian. Archived from the original on May 6, 2021. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ Ramachandran, Naman (November 29, 2020). "Darth Vader Actor David Prowse Dies at 85". Variety. Archived from the original on February 3, 2022. Retrieved February 3, 2022.

- ^ Britt, Ryan (October 21, 2016). "From Darth Revan to Vader: Ranking the 7 Most Powerful Sith in Star Wars". Inverse. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved February 8, 2022.

- ^ Richwine, Lisa; Gorman, Steve (May 3, 2019). "Peter Mayhew, actor who played Chewbacca in Star Wars movies, dies". Reuters. Archived from the original on November 3, 2021. Retrieved November 3, 2021.

- ^ Breznican, Anthony (May 4, 2018). "Watch Chewie become co-pilot in Solo: A Star Wars Story clip". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on May 7, 2018. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ Nugent, John (August 13, 2016). "R2-D2 actor Kenny Baker dies, aged 81". Empire. Archived from the original on October 17, 2016. Retrieved September 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak Nathan, Ian (May 20, 2020). "The Empire Strikes Back at 40: The making of a Star Wars classic". Empire. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ^ a b Edwards, Richard (August 12, 2021). "Star Wars timeline: Every major event in chronological order". GamesRadar+. Archived from the original on April 25, 2021. Retrieved September 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f "Star Wars Episode V The Empire Strikes Back (1980)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 9, 2020. Retrieved March 12, 2021.

- ^ White, Brett (May 24, 2018). "Solo is just the latest sci-fi event to put a 'Cheers' star in space". Deadline Hollywood. Archived from the original on October 26, 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ a b c d Morton, John (February 11, 2015). "Interview: John Ratzenberger – Major Bren Derlin, master of the improv". StarWars.com. Archived from the original on October 26, 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2018.

- ^ Wittmer, Carrie (May 4, 2018). "38 major deaths in the Star Wars movies, ranked from saddest to completely deserved". Business Insider. Archived from the original on October 26, 2018. Retrieved October 25, 2018.