Junkers A50 Junior

| A50 Junior | |

|---|---|

A50ci D-2054 in Deutsches Museum Munich | |

| General information | |

| Type | Sports plane |

| Manufacturer | Junkers |

| Designer | |

| Number built | 69 (original production) 27 (new production, May 2023) |

| History | |

| First flight | 13 February 1929 |

The Junkers A50 Junior is an all-metal sports plane designed and produced by the German aircraft manufacturer Junkers.

Designed by Hermann Pohlmann during the late 1920s, it incorporated the all-metal construction and various other principles practiced on Junkers' larger aircraft of the era. The A50 had a streamlined fuselage composed of corrugated duralumin, a low-mounted cantilever wing, and proportionally large flight control surfaces. It could be outfitted with conventional landing gear, skis or floats to suit a variety of different operational conditions; the aircraft was reportedly suitable for use in the tropics or near-arctic conditions as well as from austere airstrips. It was typically powered by a single Armstrong Siddeley Genet II engine, although other powerplants could also be fitted.

On 13 February 1929, the A50 conducted its maiden flight. During the following year, a series of eight FAI world records for altitude, range, and average speed were set on a floatplane variant of A50.[citation needed] During 1931, Marga von Etzdorf flew an A50 solo from Berlin to Tokyo, the first woman to do so.

Development

[edit]The Junkers A50 was the first sports plane designed by Hermann Pohlmann in Junkers works.[1] It had the same modern all-metal construction, covered with corrugated duralumin sheet, as larger Junkers passenger planes.[1] On 13 February 1929, the A50 conducted its maiden flight. It was promptly followed by further four prototypes, several of which were used to test different engines.[citation needed]

Junkers expected to produce 5,000 aircraft, but halted manufacturing only 69 A50s, only 50 of which were ever sold.[citation needed] The high prices probably inhibited sales. Apart from Germany, they were used in several other countries and some were used by airlines. The purchase price in 1930 in the United Kingdom was between £840 and £885.[2] Starting from the A50ce variant, the wings could be folded for easier transport.

Three German A50 took part in the Challenge international touring plane competition in July 1929, taking 11th place (A50be, pilot Waldemar Roeder) and 17th place. Three A50 took part also in the Challenge 1930 next year, taking 15th (A50ce, pilot Johann Risztics), 27th and 29th places.[1] In June 1930, a series of eight FAI world records for altitude, range and average speed were set on a floatplane variant of A50, powered by the Armstrong Siddeley Genet II 59 kW (79 hp) engine.[citation needed] During 1931, Marga von Etzdorf flew an A50 solo from Berlin to Tokyo, the first woman to do so.[3][4]

Design

[edit]

The Junkers A50 was a sports plane that featured a conventional configuration, all-metal construction, a low-mounted cantilever wing, and a stressed corrugated duralumin exterior.[1][5] It was promoted for its adaptability, being as equally suitable for use during summer as it was during the winter, on land or at sea, and in the tropics or near-arctic conditions.[6] The A50 conformed with several conventions for Junkers-built aircraft, such as the placement of the pilot in the rear seat while the passenger sat in the forward position. Both positions were provided with dual flight controls and two complete sets of instruments.[7]

The fuselage was a precisely streamlined tube of corrugated duralumin; in spite of its extensive use of metal, it was carefully designed so that achieved the typical weight limits of mixed-construction aircraft (e.g. those that used fabric and wood).[8] It was supported by a number of formers and bulkheads that had provisions for easy access that permitted both inspection and repairs to be performed.[9] The nose of the fuselage accommodated the aircraft's single engine while the rear of the fuselage tapered into a vertical wedge that extended upwards to form the fin.[8]

Having been designed to serve as a touring aircraft, several aspects of the aircraft, such as the comfort and convenience of the occupants, were addressed in detail.[10] The two seats present in the cockpit, used by the pilot and a single passenger, were relatively well-upholstered, broad, and fitted with an adjustable back and arm rests. Two separate baggage compartments were provided for the carriage of even particularly heavy suitcases; one, positioned between the two seats, was within easy reach of either occupant throughout the flight.[10] The second baggage compartment, behind the pilot's seat, was large enough for a single streamer trunk. Piping in the vicinity of the cockpit was concealed by the aircraft's double bottomed fuselage.[10]

The wing was divided into a central section, which was integral with the fuselage, and two outer sections that were joined to the centre using no more than four screws each; this aided ground transportation as well as repair work, the outer sections being readily replicable by a substitute.[5] Akin to the fuselage, the wing was covered in stressed corrugated duralumin. Structurally, it was relatively simplistic, dispensing with many typical supporting devices, such as ribs; this simplicity benefitted both production and service staff alike.[5] Several mundane defects, such as bulges, were felt to be reasonably addressable by the owner themselves. For more space-efficient storage of the aircraft, the wings could be folded rearwards on some models.[1][5]

It had a two-part elevator that was hinged to the stabilisor; it could be adjusted while on the ground.[9] The rudder was hinged to both the fin and the tip of the fuselage. The elevator, rudder and ailerons all used ball bearings, which were relatively easy to operate and service.[9] The aircraft's proportionally large flight control surfaces, thus only necessitating slight deflections, were actuated using a series of adjustable push rods. The forces and deflections of the control stick and rudder bar were harmonised.[9] It was considered to be an easy enough aircraft to fly that it would be suitable for training beginning pilots.[9]

The aircraft could be alternatively furnished with either conventional landing gear, skis or floats without the use of any special fittings.[11] The floats were relatively large, to the extent that the aircraft could remain afloat if only one of them were to be attached; to maximise buoyancy in the even of damage, the floats had internal bulkheads that formed multiple water-tight compartments. Whichever undercarriage was opted for, it would be attached to supporting points underneath the centre section of the wing.[11] The landing gear had a relatively wide track, which reduced the likelihood of the winds making contact with the ground, and lacked a continuous axle, which hindered ground movements in the presence of long grass or undergrowth. The rudder effectively offset the traditional manoeuvrability penalty incurred by the use of wide track landing gear.[12] The wheels were relatively large and sturdy, and thus suitable for use on unprepared or austere airstrips. Furthermore, the landing gear was furnished with rubber-cable style shock absorbers that were designed for durability.[12]

It was typically powered by a single Armstrong Siddeley Genet II air-cooled radial engine, which was mounted on an easily-removable frame upon the forward bulkhead, which functioned as a firewall.[6] It possessed considerable reserve power and reliability, which led to its selection to power the aircraft. The engine was enclosed by smooth sheet duralumin that left only the cylinder heads exposed.[6] The propeller was directly-driven by the engine. A special starter that involved the injection of atomized fuel into the intake manifold and a light magneto.[13] Fuel was stored in two primary tanks in the centre section of the aircraft; it was supplied to a single gravity tank via a fuel pump. The oil tank was directly adjacent to the gravity tank.[14]

New production

[edit]

In 2022, Junkers Aircraft Works began production of a modernized version of the A50 known as the A50 Junior. This new A50 features modern avionics, a 100 hp (75 kW) Rotax 912iS engine driving a composite MT-Propeller, and a ballistic parachute. As of May 2023, 27 new A50s have sold in Europe, and plans have been made for WACO Aircraft Corporation to produce aircraft for American customers.[15][16][17]

During the 2024 Sun 'n Fun Aerospace Expo, Junkers unveiled the A50 Heritage. The A50 Heritage is marketed as a more authentic version closer to the original A50.[18] It is powered by a Verner Scarlett 7U radial engine and features a two-piece glass windscreen and analog instruments.[18][19]

Variants

[edit]Original production

[edit]- A50 - Armstrong Siddeley Genet 59 kW (79 hp) radial engine

- A50ba - Walter Vega 63 kW (84 hp) radial engine (one built)

- A50be - Armstrong Siddeley Genet 59 kW (79 hp) engine

- A50ce - Armstrong Siddeley Genet II 63 kW (84 hp) engine or for export Genet Major I 74 kW, folding wings

- A50ci - Siemens-Halske Sh 13, 65 kW (87 hp) radial engine, folding wings. Originally designed to be mass-produced as a "Volksflugzeug".[20]

- A50fe - Armstrong Siddeley Genet II, 63 kW (84 hp) engine, modified airframe, folding wings

- KXJ1 - A single Junkers A-50 supplied to the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service for evaluation.

The -ce and -ci variants were produced in the largest numbers with about 25 of each on the German civil register.[21] Due to their construction, the A50 were durable aircraft and they lasted long in service. The last plane was used in the 1960s in Finland.[1] There is one A50 preserved in Deutsches Museum in Munich and another in Helsinki airport. One A50 (VH-UCC, c/n 3517) is in airworthy condition in Australia.

New production

[edit]- A50 Junior - Modernized version of the original A50 powered by a 100 hp (75 kW) Rotax 912iS engine.[16]

- A50 Heritage - Version powered by a Verner Scarlett 7U with a two-piece windscreen and analog instruments.[18]

Operators

[edit]

- Bolivian Air Force - 3 A50s transferred from Lloyd Aéreo Boliviano during Chaco War[22]

- Lloyd Aéreo Boliviano - 3 A50s used for training and light transport[23]

- South African Air Force

- South African Airways operated three aircraft

Surviving aircraft

[edit]An example is currently on display in Helsinki Airport. Registered as OH-ABB, it was flown by Väinö Bremer to Cape Town in a historic flight.[citation needed]

Specifications (A50ba)

[edit]

Data from Junkers aircraft and engines, 1913-1945,[26] Junkers: an aircraft album[27]

General characteristics

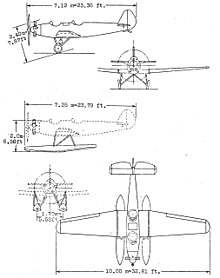

- Length: 7.12 m (23 ft 4 in)

- Wingspan: 10 m (32 ft 10 in)

- Height: 2.39 m (7 ft 10 in)

- Wing area: 13.7 m2 (147 sq ft)

- Empty weight: 340 kg (750 lb)

- Gross weight: 590 kg (1,301 lb)

- Fuel capacity: 95 L (25 US gal; 21 imp gal)

- Powerplant: 1 × Armstrong Siddeley Genet II five-cylinder air-cooled radial piston engine, 65 kW (87 hp)

- Propellers: 2-bladed fixed-pitch propeller

Performance

- Maximum speed: 164 km/h (102 mph, 89 kn)

- Cruise speed: 140 km/h (87 mph, 76 kn) on 60% power

- Landing speed: 75 km/h (47 mph; 40 kn)

- Range: 600 km (370 mi, 320 nmi)

- Endurance: Five hours

- Service ceiling: 4,200 m (13,800 ft)

- Time to altitude: 3,000 m (9,800 ft) in 21 minutes

- Take-off run (over 8 m (26 ft)-high gate): 250 m (820 ft)[28]

- Landing run (over 8 m (26 ft)-high gate): 187 m (614 ft)[28]

See also

[edit]Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f (in Polish) Krzyżan, Marian. Międzynarodowe turnieje lotnicze 1929-1934 [International aviation competitions 1929-1934], Warsaw 1988, ISBN 83-206-0637-3

- ^ "Junkers Junior". Flight. 4 April 1930.

- ^ "Marga von Etzdorf (1907-1933)". Monash University. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- ^ "THE JUNKERS A50 JUNIOR". junkersaircraft.com. Retrieved 5 July 2024.

- ^ a b c d NACA 1930, p. 1.

- ^ a b c NACA 1930, p. 5.

- ^ NACA 1930, pp. 3-4.

- ^ a b NACA 1930, pp. 1-2.

- ^ a b c d e NACA 1930, p. 3.

- ^ a b c NACA 1930, p. 2.

- ^ a b NACA 1930, pp. 4-5.

- ^ a b NACA 1930, p. 4.

- ^ NACA 1930, pp. 5-6.

- ^ NACA 1930, p. 6.

- ^ Horne, Thomas A. (5 February 2023). "Yesterday's wings, today: Reimagining a classic". www.aopa.org. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ a b Boatman, Julie (28 March 2023). "Junkers A50 Junior Unveiled to Kick Off Sun 'n Fun 2023". FLYING Magazine. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ "Futuristic retro: Junkers reintroduces A50 Junior — General Aviation News". generalaviationnews.com. 7 November 2022. Archived from the original on 2 August 2023. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- ^ a b c Trautvetter, Chad. "Junkers Takes Wraps Off of More-authentic A50 Heritage | AIN". Aviation International News. Retrieved 18 April 2024.

- ^ Wilder, Amy (2024-04-10). "Junkers Aircraft Unveils A50 Heritage Model". Plane & Pilot Magazine. Retrieved 2024-04-18.

- ^ Junkers-F13-and-A50

- ^ "Golden Years of Aviation - Main". Archived from the original on 2012-02-19. Retrieved 2012-05-30.

- ^ Tincopa & Rivas 2016, p. 61

- ^ Tincopa & Rivas 2016, p. 59

- ^ Tincopa & Rivas 2016, p. 203

- ^ Tincopa & Rivas 2016, p. 343

- ^ Kay, Anthony L. (2004). Junkers aircraft and engines, 1913-1945 (1st ed.). London, UK: Putnam Aeronautical Books. pp. 95–97. ISBN 0851779859.

- ^ Turner, P. St.J.; Nowarra, Heinz J. (1971). Junkers: an aircraft album. New York, US: Arco Publishing Inc. pp. 54–57. ISBN 0-668-02506-9.

- ^ a b Best take-off and landing results from Challenge 1930 competition (Krzyzan, op.cit., Table II)

Bibliography

[edit]- Andersson, Lennart. "Chinese 'Junks': Junkers Aircraft Exports to China 1925-1940". Air Enthusiast, No. 55, Autumn 1994, pp. 2–7. ISSN 0143-5450

- Tincopa, Amaru; Rivas, Santiago (2016). Axis Aircraft in Latin America. Manchester, UK: Crécy Publishing. ISBN 978-1-90210-949-7.

- "The "Junkers-Junior" Light Airplane (German) : A Two-Seat All-Metal Low-Wing Cantilever Monoplane" National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, 1 June 1930. NACA-AC-118, 93R19686.