Joshua 24

| Joshua 24 | |

|---|---|

Judges 1 → | |

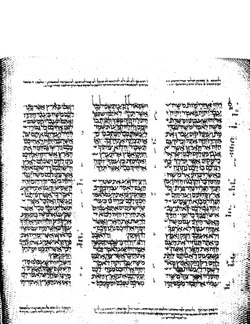

The pages containing the Book of Joshua in Leningrad Codex (1008 CE). | |

| Book | Book of Joshua |

| Hebrew Bible part | Nevi'im |

| Order in the Hebrew part | 1 |

| Category | Former Prophets |

| Christian Bible part | Old Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 6 |

Joshua 24 is the twenty-fourth (and the final) chapter of the Book of Joshua in the Hebrew Bible or in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible.[1] According to Jewish tradition the book was attributed to Joshua, with additions by the high priests Eleazar and Phinehas,[2][3] but modern scholars view it as part of the Deuteronomistic History, which spans the books of Deuteronomy to 2 Kings, attributed to nationalistic and devotedly Yahwistic writers during the time of the reformer Judean king Josiah in 7th century BCE.[3][4] This chapter records Joshua's final address to the people of Israel, that ends with a renewal of the covenant with YHWH, and the appendices of the book,[5] a part of a section comprising Joshua 22:1–24:33 about the Israelites preparing for life in the land of Canaan.[6]

Text

[edit]This chapter was originally written in the Hebrew language. It is divided into 33 verses.

Textual witnesses

[edit]Some early manuscripts containing the text of this chapter in Hebrew are of the Masoretic Text tradition, which includes the Codex Cairensis (895), Aleppo Codex (10th century), and Codex Leningradensis (1008).[7]

Extant ancient manuscripts of a translation into Koine Greek known as the Septuagint (originally was made in the last few centuries BCE) include Codex Vaticanus (B; B; 4th century) and Codex Alexandrinus (A; A; 5th century).[8][a]

Analysis

[edit]

The narrative of Israelites preparing for life in the land comprising verses 22:1 to 24:33 of the Book of Joshua and has the following outline:[10]

- A. The Jordan Altar (22:1–34)

- B. Joshua's Farewell (23:1–16)

- 1. The Setting (23:1–2a)

- 2. The Assurance of the Allotment (23:2b–5)

- 3. Encouragement to Enduring Faithfulness (23:6–13)

- 4. The Certain Fulfillment of God's Word (23:14–16)

- C. Covenant and Conclusion (24:1–33)

- 1. Covenant at Shechem (24:1–28)

- a. Summoning the Tribes (24:1)

- b. Review of Covenant History (24:2–13)

- c. Joshua's Challenge to Faithful Worship (24:14–24)

- i. Joshua's Opening Challenge (24:14–15)

- ii. The People's Response (24:16–18)

- iii. Dialogue on Faithful Worship (24:19–24)

- d. Covenant Made at Shechem (24:25–28)

- 2. Conclusion: Three Burials (24:29–33)

- a. Joshua (24:29–31)

- b. Joseph (24:32)

- c. Eleazar (24:33)

- 1. Covenant at Shechem (24:1–28)

The book of Joshua is concluded with two distinct ceremonies, each seeming in itself to be a finale:[11]

- A farewell address of Joshua to the gathered tribes in an unnamed place (Joshua 23)

- A covenant renewal ceremony at Shechem (Joshua 24)

Covenant at Shechem (24:1–28)

[edit]Joshua's final farewell address to the people of Israel in this chapter was during a ceremony in Shechem (verse 1), which has important roots in the narrative of exodus and conquest (Deuteronomy 11:29; 27; Joshua 8:30–35), and has a strong association with covenant.[12] The importance of Shechem is supported in the Book of Judges with a reference to a temple of 'Baal-berith' (or 'El-berith'), that is, the 'lord' (or 'god') 'of the covenant' (Judges 9:4, 46).[12]

This chapter exhibits unique features:[12]

- a preamble (verse 1)

- a review of the historical relationship between God and Israel (verses 2–13)

- stipulations and the requirement of loyalty (verses 14–15, 25)

- formal witnesses (verse 22, 27)

- writing a document (verses 26–27), and

- a statement of consequences (verse 20—in contrast to Deuteronomy 28, only the bad consequences of disloyalty are recorded here).[12]

The narrative in form of a literary construction resembles the ancient treaty, with real significance, that it records the actual commitment of the people of Israel to YHWH rather than to other gods, and their acceptance of this as the basis of their lives.[12] The historical context of the narrative draws on themes that belong to Israel's traditions: the origins of Israel's ancestors in Mesopotamia and the patriarchal line (verses 2–4, cf. Genesis 11:27–12:9), the Exodus from Egypt and the wilderness wanderings (verses 5–9), the conflicts in Transjordan and the Balaam story (verses 9–10, cf. Numbers 22–24), and the conquest of Canaan.[12] Archaeology has found structures at the remains of ancient Shechem and on Mount Ebal, which could be linked to this ceremony and to the one recorded in Joshua 8:30–35.[12]

Now the Israelites are to enter into a covenant renewal (following the covenants at Mount Horeb and the plain of Moab),[12] they are called to exclusive loyalty (verses 14–15), challenged with the possibility that they "cannot serve the LORD", on the basis that it seems evil,[13] unjust, unreasonable, or inconvenient to do so.[14] A strong warning is given not to think that loyalty to YHWH will be easy and to enter the covenant lightly (Deuteronomy 9:4–7).[15] This is based on the inclination of the early generations of Israel to resort to other gods from the beginning (Exodus 32; Numbers 25), that Deuteronomy 32 portrays Israel as unfaithful. The effect here could be rhetorical as the generation of Joshua is pictured as faithful (Judges 2:7,10).[15]

Verse 26

[edit]

- And Joshua wrote these words in the Book of the Law of God. And he took a large stone and set it up there under the terebinth that was by the sanctuary of the LORD.[16]

- "Large stone" (Hebrew: matzevot): This stone was rediscovered by a German archaeologist, Ernst Sellin, during the excavation in ancient Shechem in 1926-1928, standing in front of the ruins of a worship place referred to this verse as 'the sanctuary of the LORD'.[17]

- "The terebinth": an old and large tree, under which Jacob had hid the teraphim of his household (Genesis 35:4).[18] The spot of the tree is called Allon-Moreh, "the oak of Moreh" in Genesis 12:6 and Genesis 35:4.[19]

Three burials (24:29–33)

[edit]Four short units conclude the whole book, and, in a sense, the Hexateuch (Books of Genesis–Joshua). The deaths of Joshua and Eleazar, who were co-responsible for the division of the land, are recorded as the outer framing sections of these four units, signalling the end of the era of conquest and settlement (cf. Moses' death as the end of the period of exodus; Deuteronomy 34).[15] Joshua is finally given the title 'servant of the LORD' (like Moses), and he was buried in Timnath-serah on the land given to him as a personal inheritance (Joshua 19:49-50; cf. Judges 2:8-9).[15] The note concerning Israel records that they were faithful during Joshua's lifetime, agreeing with Judges 2:7, bringing the completed aspiration in Joshua of 'a people dwelling peacefully and obediently in a land given in fulfilment of God's promise'. The emphasis is on 'service', or worship, of YHWH, echoing the commitment undertaken in the covenant dialogue (verses 14–22).[15]

Verse 32

[edit]- And the bones of Joseph, which the children of Israel brought up out of Egypt, buried they in Shechem, in a parcel of ground which Jacob bought of the sons of Hamor the father of Shechem for an hundred pieces of silver: and it became the inheritance of the children of Joseph.[20]

The record of Joseph's burial connects expressly with Genesis 50:24–26 and Exodus 13:19,[15][21] placing the story of Joshua in a broader context that the 'ending' achieved in it relates to the promises to the patriarchs long time ago, the great theme in the Book of Genesis: Joseph's bones were finally buried in the land of Canaan, in Shechem, in the territory of Joseph's firstborn son Manasseh.[15]

See also

[edit]- Aaron

- Abraham

- Amorites

- Balaam

- Balak

- Beor

- Canaan

- Children of Israel

- Covenant

- Egypt

- Eleazar

- Esau

- Gaash

- Girgashite

- Hamor

- Hittites

- Hivites

- Hornet

- Idolatry

- Isaac

- Jacob

- Jebusites

- Jericho

- Jordan River

- Joseph (Genesis)

- Moab

- Moses

- Mount Seir

- Nahor, son of Terah

- Nun (biblical figure)

- Passage of the Red Sea

- Perizzites

- Phinehas

- Plagues of Egypt

- Tabernacle

- Terah

- Torah

- Zippor

- Related Bible parts: Genesis 12, Genesis 35, Genesis 50, Exodus 13, Exodus 23, Deuteronomy 6, Deuteronomy 7, Deuteronomy 11, Joshua 11, Joshua 13, Joshua 23, Judges 2, Judges 9, Ezekiel 20, Ezekiel 23

Notes

[edit]- ^ The whole book of Joshua is missing from the extant Codex Sinaiticus.[9]

References

[edit]- ^ Halley 1965, p. 164.

- ^ Talmud, Baba Bathra 14b–15a)

- ^ a b Gilad, Elon. Who Really Wrote the Biblical Books of Kings and the Prophets? Haaretz, June 25, 2015. Summary: The paean to King Josiah and exalted descriptions of the ancient Israelite empires beg the thought that he and his scribes lie behind the Deuteronomistic History.

- ^ Coogan 2007, p. 314 Hebrew Bible.

- ^ Coogan 2007, pp. 350–352 Hebrew Bible.

- ^ McConville 2007, p. 158.

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 35–37.

- ^ Würthwein 1995, pp. 73–74.

- ^

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). "Codex Sinaiticus". Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Firth 2021, pp. 30–31.

- ^ McConville 2007, pp. 173–174.

- ^ a b c d e f g h McConville 2007, p. 174.

- ^ Joshua 24:15: King James Version

- ^ Benson, J. (1857), Benson Commentary on the Old and New Testaments, Joshua 24, accessed on 25 August 2024

- ^ a b c d e f g McConville 2007, p. 175.

- ^ Joshua 24:26 ESV

- ^ Stephen Langfur. Ancient Shechem (Tell Balata) at Nablus (Shechem) Archived 2019-06-17 at the Wayback Machine. NET Near East Tourist Agency. Accessed 8 July 2018.

- ^ Exell, Joseph S.; Spence-Jones, Henry Donald Maurice (Editors). On "Joshua 24". In: The Pulpit Commentary. 23 volumes. First publication: 1890. Accessed 24 April 2019.

- ^ Cambridge Bible for Schools and Colleges. Joshua 24. Accessed 28 April 2019.

- ^ Joshua 24:32: KJV

- ^ Coogan 2007, pp. 351–352 Hebrew Bible.

Sources

[edit]- Beal, Lissa M. Wray (2019). Longman, Tremper III; McKnight, Scot (eds.). Joshua. The Story of God Bible Commentary. Zondervan Academic. ISBN 978-0310490838.

- Coogan, Michael David (2007). Coogan, Michael David; Brettler, Marc Zvi; Newsom, Carol Ann; Perkins, Pheme (eds.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocryphal/Deuterocanonical Books: New Revised Standard Version, Issue 48 (Augmented 3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195288810.

- Firth, David G. (2021). Joshua: Evangelical Biblical Theology Commentary. Evangelical Biblical Theology Commentary (EBTC) (illustrated ed.). Lexham Press. ISBN 9781683594406.

- Halley, Henry H. (1965). Halley's Bible Handbook: an abbreviated Bible commentary (24th (revised) ed.). Zondervan Publishing House. ISBN 0-310-25720-4.

- Harstad, Adolph L. (2004). Joshua. Concordia Publishing House. ISBN 978-0570063193.

- Hayes, Christine (2015). Introduction to the Bible. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300188271.

- Hubbard, Robert L (2009). Joshua. The NIV Application Commentary. Zondervan. ISBN 978-0310209348.

- McConville, Gordon (2007). "9. Joshua". In Barton, John; Muddiman, John (eds.). The Oxford Bible Commentary (first (paperback) ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 158–176. ISBN 978-0199277186. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- Rösel, Hartmut N. (2011). Joshua. Historical commentary on the Old Testament. Vol. 6 (illustrated ed.). Peeters. ISBN 978-9042925922.

- Webb, Barry G. (2012). The Book of Judges. New International Commentary on the Old Testament. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 9780802826282.

- Würthwein, Ernst (1995). The Text of the Old Testament. Translated by Rhodes, Erroll F. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-0788-7. Retrieved January 26, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Jewish translations:

- Yehoshua - Joshua - Chapter 24 (Judaica Press). Hebrew text and English translation [with Rashi's commentary] at Chabad.org

- Christian translations:

- Online Bible at GospelHall.org (ESV, KJV, Darby, American Standard Version, Bible in Basic English)

- Joshua chapter 24. Bible Gateway