John the Armenian

John the Armenian was a Byzantine official and military leader of Armenian origin. There is no written account of his physical appearance or confirmation of the year he was born. John served as financial manager of the campaign and was a close friend of Belisarius. He was killed during the Vandalic War in 533.[1] John the Armenian was the linchpin general of the Byzantine army during the Vandalic war.

John the Armenian lived the last few years of his life during the age of Justinian. Justinian came to power in 527 and would reign until 565 as emperor of the Byzantine Empire.[2] A war erupted called the Vandalic War in 533. The Romans attacked during a time of dynastic strife.[3] The Vandal kingdom presented an important economic boon in that it was a major grain supplier. War thus would provide the empire with large stores of grain and remove one of the nation's main imperial rivals.[4]

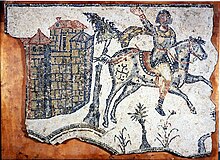

John the Armenian was present within the army of Belisarius from the onset of the Vandalic War and was part of the army landing in Tunisia in 533. He commanded the vanguard and sections of cavalry for Belisarius including auxiliary units like the Huns. This post would prove exceptionally important due to the entire Vandal army being made up of light cavalrymen. The Roman army had a mobility disadvantage compared to the Vandals, John and other cavalrymen were important in keeping the army from being harassed or run down. John the Armenian commanded the Byzantine vanguard at the Battle of Ad Decimum, and killed Ammatas, the brother of the Vandal king Gelimer near Carthage on September 13 533.[5] This was a large morale hit to the Vandal king and his army. Unlike the Byzantines more meritocratic officers, many Vandal commanders were royal family. John pursued the fugitives of the defeated Vandal army until he was recalled to Carthage where he rejoined Belisarius with his army and 600 Hunnic auxiliaries. John aided Belisarius in the occupation of Carthage. After taking the Vandal capital, the regrouped Vandal army returned and sought a decisive field battle. John fought in the center of the Byzantine army during the subsequent Battle of Tricamarum. This battle was a near disaster as Belisarius lost control of the army and its cohesion.[1] John regained the initiative and charged the Vandal center with his cavalry reinvigorating the Roman legion and killing a Vandal commander named Tzazon. John's recovery saved them the battle and likely the campaign. After the Byzantine victory there, Belisarius tasked him with Gelimer's pursuit and gave him 200 cavalry. John almost caught up with Gelimer, but he was accidentally killed by Uliaris, one of Belisarius' bodyguards.[1][6] According to Procopius, John was much loved among the soldiers and Belisarius. John was widely mourned and Belisarius set aside funds for the yearly maintenance of John the Armenian's grave.

The Vandalic War ended in success in 534 with the dissolution of the entire kingdom. The commander of the army Belisarius was granted a triumph, elected Consul, and became a major political figure as a result of the war.[7] However, the peace terms later sparked a war with the Ostrogothic kingdom. Disputes over Sicily which was a former Vandal possession and sought by the Ostrogoths coincided with grave dynastic turmoil that exploded into outright war with the Ostrogothic Kingdom in Italy. The outcomes of these wars lead to the weakening of the Byzantine Empire as it depleted its gold reserves and manpower.[2]

Influence of the Africa Campaign

[edit]The African campaign cost the Byzantine Empire over 100,000 pounds of gold[1] and saw the rise of one of the most prestigious Roman generals, Belisarius. However, he nearly suffered defeat at the hands of the Vandals. If Belisarius lost, it is unlikely that he would have recovered and the campaign would have been lost. The truth is that Belisarius was losing the battle of Tricamarum until the intervention of John the Armenian. Tricamarum was a decisive Roman victory that would not have been won without John the Armenian. If the empire had suffered humiliation in Africa perhaps it would not have moved on to invade Italy, as the lessons learned from Africa were applied in Italy, from pouncing on dynastic turmoil to efficient logistics and local management. Belisarius may not have enjoyed the prestige he did without the work of John the Armenian.[8]

Historiography

[edit]It must be noted that the only mentions of John the Armenian occur within Procopius History of the Wars Book III and IV. John the Armenian is mentioned sparingly and only within the confines of 533. The only primary source with knowledge of his exploits is Procopius. However, Procopius is the major source historians rely on for information including warfare and politics in the age of Justinian. Despite the biases apparent in other works by Procopius[9] History of the Wars is considered a well learned and accurate account of the era. Beyond History of the Wars there is no mention of John the Armenian in any contemporary sources.[10]

John the Armenian connects into a wider trend in the 6th century Roman world. He was part of a last breath of expansion due to relative prosperity in the Byzantine empire.[11] The Justinian restoration was fueled by bold and capable military leaders like John the Armenian. The lessons learned by this generation of generals saw the Byzantine empire hit its greatest territorial extent and then decay from then on. While there is little discussion surrounding John himself, Belisarius and other men like John shaped the geopolitical world of the 6th century Mediterranean.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Dewing, H.B. (2005). History of the Wars Book III and IV. Gutenberg Project. pp. 144–193 and Index.

- ^ a b Maas, Michael (2005). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge. pp. ch 2 and 19.

- ^ Merrils, Andrew (2017). Vandals, Romans and Berbers. pp. Part one.

- ^ Witby, Michael (2021). The Wars of Justinian I. Pen and Sword Military. pp. 144–193.

- ^ Heather, Peter (2018). Rome Resurgent: War and Empire in the Age of Justinian. Oxford University Press. pp. ch 1–3.

- ^ Stevens, Susan (2016). North Africa under Byzantium and Early Islam. Washington DC: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library. pp. 13–23.

- ^ Hughes, Ian (2009). Belisarius: The Last Roman General. Pen and Sword Military. pp. ch 6–7.

- ^ Souritis, Yannis (2018). A Companion to the Byzantine Culture of War. Leiden: Brill. pp. 125–159, 160–190, 259–307.

- ^ Sarris, Peter, Procopius (2007). The Secret History. Penguin. pp. 9–17.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Montinaro, Federico (2022). A Companion to Procopius of Caesarea. pp. 255–274.

- ^ Vasil'ev, A.A. (2004). History of the Byzantine Empire 324-1453. Madison: Wisconsin University Press. pp. ch 3.

- Dewing, H.B 2005. History of the Wars Book III and IV. Gutenberg Project.

- Heather, Peter. 2020. ROME RESURGENT : War and Empire in the Age of Justinian.

- Hughes, Ian. 2009. Belisarius. Pen and Sword.

- Maas, Michael. 2005. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge University Press.

- Meier, Mischa, and Federico Montinaro. 2022. A Companion to Procopius of Caesarea. Leiden: Brill.

- Merrills, Andrew. 2017. Vandals, Romans and Berbers. Routledge.

- Procopius, G A Williamson, and Peter Sarris. 2007. The Secret History. London; New York: Penguin.

- Sarris, Peter. 2009. Economy and Society in the Age of Justinian. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Stevens, Susan T, and Jonathan Conant. 2016. North Africa under Byzantium and Early Islam. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Research Library And Collection.

- Stouraitis, Yannis. 2018. A Companion to the Byzantine Culture of War, Ca. 300-1204. Leiden: Brill.

- Vasilʹev, A A. 2004. History of the Byzantine Empire 324-1453. Madison; London: University Of Wisconsin Press.

- Whitby, Michael. 2021. The Wars of Justinian I. Pen and Sword Military.