John Vassos

John Vassos | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | John Plato Vassacopoulos 23 October 1898 Sulina, Romania |

| Died | 7 December 1985 (aged 87) Norwalk, Connecticut |

| Occupation | Author, industrial designer |

| Nationality | |

| Genre | Industrial Design |

| Notable works | Contempo Phobia Perey Turnstile, RCA TRK12 television, RCA Victor Special phonograph, RCA 9YJ 45rpm phonograph |

| Spouse | Ruth Vassos |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1940–1945 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Commands | Office of Strategic Services - OSS |

| Battles / wars | Second World War Mediterranean Theater of Operations |

| Awards | |

John Vassos (born John Plato Vassacopoulos; 23 October 1898 – 6 December 1985) whose career as an American industrial designer and artist helped define the shape of radio, television, broadcasting equipment, and computers for the Radio Corporation of America for almost four decades. He is best known for both his art deco illustrated books and iconic turnstile for the Perey company, as well as modern radios, broadcast equipment, and televisions for RCA. He was a founder of the Industrial Designers Society of America, in 1965, serving as its first chairman simultaneously with Henry Dreyfuss as its president. Vassos' design philosophy was to make products that were functional for the user.

A decorated veteran of World War II, Vassos was chief of the OSS "Spy School" in Cairo, Egypt from 1942 to 1945.[1]

Early years

[edit]Vassos was born in Sulina, Romania to Greek parents, and his family moved when he was young to Istanbul, Turkey. He became a deck hand with the Allies during World War I, and survived the torpedoing of a Belgian ship on which he was serving. After the war ended, he emigrated to the United States in 1919.[2]

Career

[edit]Vassos moved to Boston, Massachusetts in 1919, where he attended the Fenway Art School at night. He studied alongside[clarification needed] American artist John Singer Sargent and worked as an assistant for Joseph Urban.[3] In 1924 he moved to New York, where he attended the Art Students League of New York, studying under George Bridgman, John Sloan, and others.[2] He opened his own studio creating window displays for department stores, like Wanamakers, murals, and advertisements for Saks Fifth Avenue, Bonwit Teller, and Packard Motor Cars in his unique black and white illustrated style.[3] At the same time, he illustrated a series of books by Oscar Wilde for E.P. Dutton followed by others including Phobia on which he based his life-long design focus on psychology, his area of expertise as noted by Fortune Magazine's list of top designers in the country.[4] He entered the emergent field of industrial design and was hired by rapidly-growing RCA Victor, under the leadership of David Sarnoff, who discovered Vassos while painting murals at the WCAU skyscraper in Philadelphia.[5] The company had recently acquired Victor Phonograph, built Radio City, and owned NBC Broadcasting, but needed to amplify and modernize their radio manufacturing business. By hiring Vassos, an up-and-coming industrial designer who created their first Styling department, launched Vassos on a four-decade relationship with the company for whom he designed hundreds of items, while also consulting for numerous other clients like Coca-Cola, Waterman, Universal Artists, Remington, and the United States Government.[4] Vassos's work as an interior designer included the Chrysler Building apartment of photographer Margaret Bourke-White, Nedick's Hot Dog stands, displays for RCA in department stores and the World's Fair, and many others for which he employed modular furniture.[6] He eschewed trendy styles like the extreme-streamlined look, popular in the 1930s, and favored the clean, modern look unadorned with unnecessary elements. He expressed his design philosophy for magazines like Pencil Points[6] and in lectures on modern design and art.[7] Although he was hailed as a top designer in the United States during the 1930s, he slipped away from the spotlight of his industrial design peers like Raymond Loewy, Henry Dreyfuss, and Norman Bel Geddes, largely because he did not open a large firm.[8] Unique among the industrial designers of the 20th century, his work was focused on the intersections between interior decorating, furniture design, and the shapes of phonographs, radios and televisions.[9] His contributions include creating a futuristic living room including television, the slide rule dial on radios, emphasis on the haptic experience of media (knobs and buttons), and the "user experience," years before this term was coined.[8]

Books

[edit]

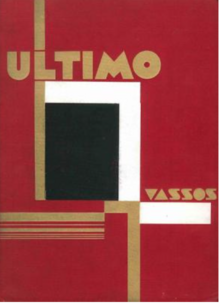

Vassos gained acclaim as an illustrator prior to his rise as an industrial designer. Between 1927 and 1935, Vassos illustrated many books, including Salome, The Ballad of Reading Gaol, and The Harlot's House and Other Poems – three literary works by Oscar Wilde published by E. P. Dutton. Vassos's iconic subjective illustrations were influenced by cinema and reflected cubist and constructivist, geometrical styles. They were often in black and white gouache (opaque watercolor) and well suited for reproduction in mass media. Contempo (1929) written by his wife Ruth Vassos with images by Vassos launched career as a modernist artist. Contempo is best understood as an exploration of American society during a moment of great transformation in which the American tempo is celebrated as "a certain sharp staccato rhythm almost like a riveting machine that exists nowhere else in the world," as Ruth Vassos wrote.[10] The book also critiques the institutions of mass culture and commercial society.[11] Phobia was his most influential book – inspired by his friend Freudian psychoanalyst Harry Stack Sullivan.[5] It reflects a modern landscape through the perspective of those who suffer from phobias and shaped Vassos's industrial design philosophy. It was performed as a dance by choreographers Gluck Sandor and Felicia Sorel with sets designed by Vassos and had a limited run of 1,000 books. Articles derived from it were published in Esquire Magazine.[12] Ultimo (1930) presented a dystopic vision of a future underground society using streamlined motifs and was a response to debates about an urban landscape dominated by skyscrapers by writers like Lewis Mumford. This was followed by: Humanities (1934), Dogs Are Like That, (1941), Beatrice the Ballerina (under the pseudonym Ivan Vassilovitch, 1943), Rex and Lobo (1946), and illustrations for A Proverb for It: 1510 Greek Sayings (1945). Renewed interest in art deco and in Vassos brought new interest in his illustrated work. In 1976, Dover Books published Contempo, Phobia and Other Graphic Interpretations with a foreword by P.K. Thomajan.[13] In 2009, Dover Books republished Phobia with an introduction by David A Berona.

Industrial design

[edit]

In 1924, Vassos created his first industrial design product, a lotion bottle popular as a hip flask during Prohibition. In 1933 he designed the widely popular Perey turnstile still used in many subway stations.[14] Other notable designs included a streamlined paring knife, Hohner accordions and harmonicas, computers, an electron microscope for the RCA company, corporate logos, and Remington shotguns. These highly functional and visually striking designs include major forms of media in the 20th century. His strengths in designing media tools for consumers and professionals alike set him apart from other industrial designers. Vassos designed numerous radios, phonograph players, the Constellation jukebox for the Mills Company, and total environments for movie theaters, international expositions, and restaurants. John Vassos's contributions to public projects, like the famous RCA Building for the 1939/1940 New York World's Fair, have been overlooked for decades. John Vassos considered RCA, NBC, United Artists, Waterman Pens, Coca-Cola, Wallace Silver, Nedick's, Mills Industries, and the United States Government among its scores of national clients.[15] Vassos designed the cabinets of the RCA Corporation's first commercially available television sets.[16] For the 1939 New York World's Fair he created a novel TV cabinet in transparent Lucite plastic as well as the company's first mass-produced television sets – the TRK12, TRK-9, and TRK-5. These sets were sold at major department stores in the New York metropolitan area.[17] The TRK-12 is noted as one of the most significant mass-produced designs of the 20th century[18] and held in many major museum collections including the Smithsonian.[19]

Vassos also envisioned interior spaces for television. His "Musicorner" for America at Home Pavilion or "Living Room of the Future" as it was known was displayed 1939/1940 New York World's Fair, and was among the designer led creation of an integrated media-centered room which combined radio, television, and record player housed within a single cabinet.[20] In 1941, Vassos designed the RCA 621TS television set, which was slated to be sold the following year as a 1942 model. However, after Pearl Harbor and America's entry into World War II, manufacture of most consumer goods (including radio and television sets) was prohibited for the duration of the war, so the design was withheld until the end of the war, when it was brought out in 1946 as a limited run model until the post-war designs were fully ready.[21] His industrial design contributions at RCA spanned over 40 years and included the designs for microphones, broadcast equipment, transmitter buildings, RCA's first color television camera which became the standard in the field, and the RCA 501 solid-state computer among many other hundreds of products for the company.[15]

In the post war years, he designed pavilions for U.S. Trade Fairs (Karachi, New Delhi), for RCA at the Brussel's World's Fair and the 1964 New York World's Fair, modernized movie theaters for the United Artists Company including Grauman's Egyptian Theater in Los Angeles, export radios, radar equipment, televisions cameras, and boom stands for RCA, and designed shotguns for Remington Arms among other jobs. In 1960, he created an "advance design center" or think tank for RCA bringing together architects and designers like Paul Rudolph and Melanie Kahane to envision portable computers and television screens, a visionary proposition when computers were only used for businesses.[23] Record players and microphones he designed can sell for thousands of dollars each at auction. His portable aluminum record players ca.1937,[22] the RCA Victor Special, are in the collections of the Brooklyn Museum, Yale University Art Gallery, the Victoria and Albert Museum, the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, and many other collections, regarded as iconic of modernistic design. Like many of Vassos' designs of media technologies, they are devoid of direct references to streamlined vehicles and inspired by the spare aesthetics of the Bauhaus School.[24] His papers are collected at Syracuse University and at the Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution in Washington DC.[citation needed]

Industrial design profession

[edit]John Vassos was a founder of the industrial design profession in the United States and strived for excellence in the field. He became the president of the American Designers' Institute (later Industrial Designers Institute) in 1938 - 1941 leading and growing the organization, adding members like Kem Weber, Eva Zeisel, Walter von Nessen, Alfons Bach, and Belle Kogan.[7] In 1952, Vassos along with fellow American Design Institute colleagues Alexander Kostellow, László Moholy-Nagy and others, developed a prototype for a four-year industrial design education, which was grounded in the Bauhaus School design principles. This set the standard for collegiate industrial design education.[25] Vassos was instrumental in the formation of the Industrial Designer's Society of America (IDSA), a merger between the Industrial Designers Institute and the Society of Industrial Designers, and was its first chairman of the board with Henry Dreyfuss as its first President. He insisted that designers should be concerned with the legal status of their profession, and helped establish educational and licensing requirements.

World War II, wartime honors and legacy with the Office of Strategic Services (OSS)

[edit]John Vassos enlisted into the United States Army when World War II began and went to war as captain in the Engineering Corps in charge of camouflage for the 3rd Air Force Headquarters.[26] He was identified as a prime asset for America's newly created intelligence service founded by William J. Donovan: the Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Due to his extraordinary leadership, cleverness, unsurpassed skill-set and knowledge of the Mediterranean, as well as his fluency in Greek and Turkish, he was assigned to the 'Secret Intelligence' (SI) and 'Special Operations' branches (SO) of the Office of Strategic Services and promoted to major and put in charge of the secluded ‘Spy School’ in Cairo, Egypt.[27] This clandestine training center was a Camp X-type facility, situated in a remote, upper-class suburb of Cairo along the Nile River, known as "Area A." It was a palace owned by the brother-in-law of King Farouk of Egypt, and rented to the OSS, called Ras el Kanayas.[28][29] Major Vassos was the Commanding Officer (CO) of the ‘Spy School’ for the duration of the war.[1] Under Vassos' tutelage, many agents were trained and sent on missions behind enemy lines: primarily to Greece, the Balkans, and Italy.[30] Vassos' detailed drawings, for the OSS training manuals and films, were used by prospective agents and attest to his unique artistic talent.[31] For his meritorious service, Vassos was promoted to the rank of colonel at the war's conclusion by the Office of Strategic Services and the United States Army.[32][self-published source] Considered by Vassos to be the highest honor he had received was from Greece: the Gold Cross of the Order of the Phoenix (Greek: Χρυσούς Σταυρός του Τάγμα του Φοίνικος) in 1966. It is bestowed upon individuals of non-royal status who have elevated Greece's international prestige, and was signed by King Constantine II of Greece for his "contribution to the Allied triumph over Nazi Germany while exemplifying the Hellenic paradigm of excellence."[33]

Personal

[edit]Vassos lived in Greenwich Village and the Upper West Side of New York City with his wife, Ruth Vassos, and settled in the Silvermine neighborhood in Norwalk, Connecticut in the 1930s. He was an influential leader of the Silvermine Guild and an avid hunter. His offices were in Camden, New Jersey, Manhattan and at his home.

Death

[edit]John Vassos died in Norwalk, Connecticut in 1985.[34]

Design work

[edit]John Vassos designed groundbreaking products of 20th-century America, particularly for media technologies. Among them were:

- Glass screw top bottle for Armand Company which doubled as a flask during Prohibition

- Turnstile for the Perey Company[35] which became the standardized design for turnstiles in mass transit and sports arenas

- Utensils for Wallace Silver

- Moby Dick Knife and No Fumble Rack for Remington-Dupont

- Portable Phonograph RCA Victor Special M circa 1935

- RCA knob, 1935 (at the request of the U.S. Navy), became the standard

- Created RCA "Magic Brain" advertising campaign

- RCA Radio Model 6K10 (1936)

- RCA Radio Model 96X (1939)

- RCA New Yorker Model 5Q56 (1939)

- RCA Radio Super Six Model 15X (1941)

- RCA New Yorker Series Radios (SQS, 6Q8, 4QU, 6Q7) - 1939

- RCA Microphone and Stand, Model No. 77-B1, 1937-1938

- RCA 5DX Transmitter (broadcast equipment)

- Musicorner at the America at Home Pavilion at the 1939/1940 New York World's Fair

- RCA Radio Model Q33 (1940)

- TRK-12 Television for RCA, the first mass-produced television for the company which premiered at the 1939 New York World's Fair

- Waterman "Hundred Year" pen in colorful lucite with streamlined design, 1939

- Bench for Electric Piano, Story & Clark (1940)

- Model B RCA Electron Microscope (built by Vladimir Zworykin and James Hillier)

- Echo Elite Harmonica for Hohner

- RCA TK-30 television camera

- Mills Constellation jukebox (1947)

- Remington Model 11-48SA and Sportsman Model 48SA shotguns for Remington Arms, 1948

- Export radios for Latin America and Europe for RCA[36] (1949)

- Line of air conditioners for RCA introducing the "air-flow" theme

- 9-JY Model RCA Victor 45 rpm phonograph, this was the first 45-rpm phonograph with automatic changer (1949) and marked the emergence of RCA's newest record format.

- Large mural in the lobby of the Rivoli Theatre in New York City[37]

- Pavilions for the United States Trade Fairs in Karachi and New Delhi, led to RCA introducing television there for the first time.

- RCA Pavilion for the Brussels World's Fair

- RCA Pavilion interior for the 1964 New York World's Fair

- RCA 501 Solid State computer (1958)

- Marchesa Piano Accordion for Hohner (1960-1970)

References

[edit]- ^ a b Hueck Allen, Susan (2013), "11", Classical Spies: American Archaeologists with the OSS in World War II Greece, Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan, p. 204, ISBN 978-0472117697

- ^ a b David Shirey, "An Esthetic Evangelist," New York Times, 27 February 1977.

- ^ a b Vassos, John (1976). Contempo, Phobia and Other Graphic Interpretations. Dover. pp. vii–x.

- ^ a b "Both Fishand Fowl" by George Nelson, Fortune, February 1934, p. 43.

- ^ a b Vassos, John (1976). Contempo, Phobia, and Other Graphic Interpretations. Dover. pp. viii.

- ^ a b Vassos, John (Summer 2003). "A Small Modern Restaurant". Pencil Points: 889–896.

- ^ a b Shapiro, Danielle (2016). John Vassos: Industrial Design for Modern Life. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 208–210.

- ^ a b Shapiro, Danielle (2016). John Vassos: Design for Modern Life. University of Minnesota Press. pp. xi.

- ^ Sterne, Jonathan (2012). MP3: The Meaning of a Format. Duke University Press. p. 15.

- ^ John and Ruth Vassos, Contempo (E.P. Dutton)

- ^ Benton, Charlotte (2003). Art Deco: 1910-1939. Bulfinch Press. pp. 13. ISBN 978-0821228340.

- ^ John Vassos, "The Case for Acrophobia," Esquire, February 1937, 85.

- ^ Danielle Shapiro, John Vassos: Industrial Design for Modern Life (2016, University of Minnesota Press).

- ^ Fortune. "Both Fishand Fowl" by George Nelson, Fortune, February 1934, pp 40-43, 88.

- ^ a b Schwartz, Danielle (Summer 2009). "Modernism for the Masses: The Industrial Design of John Vassos". Archives of American Art Journal. 46 (1/2): 4–23. doi:10.1086/aaa.46.1_2.25435119. JSTOR 25435119. S2CID 193376936.

- ^ Pulos, Arthur (1988). The American Design Adventure: 1940-1975. MIT Press. pp. 299. ISBN 9780262161060.

- ^ "1939 RCA TV sets". TVHistory.tv. Archived from the original on 11 March 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ^ Gantz, Carroll (2005). Design Chronicles: Significant Mass Produced Designs of the 20th Century. Schiffer Design Book. p. 95.

- ^ Kurin, Richard (2016). The Smithsonian's History of America in 101 Objects. Penguin. ISBN 978-0143128151.

- ^ Shapiro, Danielle (2016). "New Technologies: John Vassos and Television Design". Smithsonian: Archives of American Art. Smithsonian.

- ^ "RCA 621TS designed in 1941, sold in 1946".

- ^ a b ""RCA Victor Special" model phonograph". DMA Dallas Museum of Art.

- ^ Shapiro, Danielle (2016). "New Technologies: John Vassos and Television Design". Smithsonian: Archives of american Art. Smithsonian.

- ^ Benton, Charlotte (2003). Art Deco: 1910-1939. Bullfinch Press. pp. 356–357. ISBN 978-0821228340.

- ^ "John Vassos, FIDSA". IDSA. Summer 2017.

- ^ Letter to Jerry Steichler from John Vassos, 27 February 1962, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Box 8.

- ^ Doundoulakis, Helias (2014), "1", Trained to be an OSS Spy, Bloomington, IN: Xlibris, p. 14, ISBN 978-1499059830

- ^ Hueck Allen, Susan (2013), "7", Classical Spies: American Archaeologists with the OSS in World War II Greece, Ann Arbor, Michigan: The University of Michigan, p. 134, ISBN 978-0472117697

- ^ Doundoulakis, Helias (2014), "1", Trained to be an OSS Spy, Bloomington, IN: Xlibris, p. 14, ISBN 978-1499059830

- ^ "VIDEO: How to Lie for Your Life from World War II Spy School | Smithsonian Channel". smithsonianchannel.com. Retrieved 8 January 2017.

- ^ Doundoulakis, H, Gafni, G: Trained to be an OSS Spy, Ch. 16, "True Actors of the War" p. 133, Xlibris, 2014.

- ^ Doundoulakis, H, Gafni, G: Trained to be an OSS Spy, Ch. 32, "Revisiting the Good Life" p. 304, Xlibris, 2014.

- ^ Shapiro, Danielle (2016). John Vassos: Industrial Design for Modern Life. University of Minnesota Press. p. 207.

- ^ "John Vassos". The New York Times. New York. 1985.

- ^ Orr, Emily (Summer 2017). "John Vassos: Industrial Design for Modern Life". Journal of Design History. 29 (4): 435–437. doi:10.1093/jdh/epw045.

- ^ John Vassos, "Designing Export Radios," Radio Age, July 1949, page 25.

- ^ Letter to Jerry Streichler from John Vassos, 27 February 1962, Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Box 8.

Sources

[edit]- John Vassos New York Times obituary, published 10 Dec. 1985

- John Vassos Papers: Syracuse University

- John Vassos papers, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- "Television in the World of Tomorrow," by Iain Baird, ECHOES, Winter, 1997

- Illustrators: John Vassos[usurped], JVJ Publishing

- John Vassos: Industrial Design for Modern Life, Spring 2016, University of Minnesota Press, Danielle Shapiro.

- Corrado Farina (IT), Psicoanalisi nero su bianco. John Vassos e le fobie dell'umanità, "Charta", Padova, n. 95, 2008, pp. 50–54.

External links

[edit]- John Vassos: Industrial Design for Modern Life, Spring 2016, University of Minnesota Press, Danielle Shapiro.

- New Technologies: John Vassos and Television Design, Smithsonian Magazine

- John Vassos Papers, Archives of American Art

- Roughly Speaking Podcast: John Vassos and the Shape of Things to Come

- Major John Vassos, Chief Training Officer for the Middle East Theatre for the OSS, 1944-1945

- The Training of Agent and Radio Operator Middle East Theater, circa 1940

- The OSS Society

- Trained to be an OSS Spy by Helias Doundoulakis/Gabriella Gafni

- Smithsonian Channel, World War II Spy School

- OSS Society Donovan Award Dinner 2015