John Goldie (philosopher)

John Goldie | |

|---|---|

John Goldie, philosopher | |

| Born | 1717 Craig Mill, East Ayrshire, Scotland |

| Died | 1811 (aged 93–94)[1] Kilmarnock, Scotland |

| Occupation(s) | miller cabinet maker wine merchant philosopher mathematician astronomer theologian |

John Goldie, Goudie or Gowdie (1717–1811) the 'Philosopher'[2] was a friend of the poet Robert Burns who was born the son of a miller at Craigmill on the Cessnock Water in East Ayrshire, Scotland. He was a miller, mechanic, cabinet maker, later a wine merchant and had interests ranging from the study of mathematics and astronomy to that of theology, publishing several books, in particular in 1780 the popular three volume Essays on various Important Subjects Moral and Divine, being an attempt to distinguish True from False Religion, a publication that became generally known as 'Goudie's Bible' and raised him to national prominence.[3][1] The name 'John Goldie' will be used throughout for consistency.

Life and character

[edit]

Often referred to as the philosopher,[4] Goldie was born in 1717 at Craigmill (NS 482 329), a flour mill on the Cessnock Water that had once been the mill of the Barony of Haining-Ross, worked by his family for nearly 400 years.[5] His parents were Anna Farquhar and John Goudie who married at Craigie in Ayrshire on 6 November 1714. He had four brothers and sisters, two of whom may have died in infancy.[6]

He was "one of the most remarkable men of his time and place".[1] Craigmill, situated on the Cessnock Water near the barony wood of Craigenconnor, was demolished by 1908 and nothing substantial remains on site.[7] He is said to have died in 1808 aged 92;[8] some authors say 1809[9] or 1811.

At the age of 14 (1735), and with basic tools and materials, he designed and constructed a miniature corn mill at Craigmill on the Cessnock Water. Mr Wallace of Kelly, then living at Cessnock House near Galston was so impressed with the novel design of this mill that brought Earl of Marchmont to see it. The Earl gave Goldie three shillings as a reward with which to buy an iron spindle for the wheel.[6]

He moved to Kilmarnock and became a cabinet maker without undergoing an apprenticeship, later a successful wine and spirit merchant in a large and popular store at Kilmarnock Cross.[10] He had interests ranging from the study of astronomy and science to that of theology. He also speculated in canals, railways and coal mines.[3][1] As a cabinet maker he made a highly carved ornate clock case of mahogany, showing the whole five orders of architecture and of such artistry that its price was beyond that of most people, however the Duke of Hamilton came to hear of it, purchased it for £30, a large sum at that time, and placed in Hamilton Palace.[2][11]

Goldie was largely educated by his mother Anna, as well as being self-educated, as he was of a studious nature from boyhood reading many books and becoming conversant with "some of the more abstruse sciences."[10]

His upbringing was decidedly Calvinistic[2] but he later travelled regularly on Sundays the 20 mile round trip from his father's house at Craigmill to Kilmaurs to hear Mr Smeaton, the famous anti-burgher minister of that parish, preach.[12][13] He had developed a strong 'free thinking' attitude through his reading of Dr Taylor of Norwich's publication On Original Sin.[14]

He is recorded to have been a man of unblemished character who had many good friends, many of whom were the leading lights of Kilmarnock. He also corresponded with "literary men of celebrity".[8]

Publications

[edit]

Some confusion exists in the literature as to the dates and titles of his works. His first publication, printed in Glasgow was, Essays on various Important Subjects Moral and Divine, being an attempt to distinguish True from False Religion. This expressed his then unorthodox views on original sin and upon the interpretation of many of the scriptures greatly concerned the 'Auld Lichts' or more fundamentalist Presbyterians.[13] In 1785 he published a second edition now titled Essays on Various Subjects, Moral and Divine, in one volume, by John Goldie; to which is added, the gospel recovered from a Captive State, in five volumes. By a Gentle Christian.[8]

In 1786 he published The Gospel Recovered from its Captive State which confirmed his full and formidable opposition to the 'Auld Licht' order that he had supported as a younger man.[15] In 1808 he had printed at Kilmarnock a book titled Conclusive Evidences Against Atheism.[8] His last published work in 1809 was A Treatise upon the Evidences of a Deity.[2] Dougal states that in 1811, aged over ninety and therefore just a few years before his death, he published his last work, Evidences against Atheism.[4] He died before completing his work on a book to be titled A Revise, or Reform of the Present System of Astronomy.[8]

The Beanscroft Devil

[edit]

An unusual story has John Goldie at its heart, and that is the tale of the 'Beanscroft Devil' set at the time of the poet Robert Burns:

Beanscroft Farm lies on Grassyards Road in the parish of Fenwick in East Ayrshire a few miles to the west of Kilmarnock. The farmer there was known as a good, honest, hard working and God fearing member of the community. However, strange happenings at the farmhouse and in the byres slowly convinced him and his family that he was being tormented by the Devil himself. The other disturbances had started in a minor way with sounds and movements that could be ascribed to the wind or the cat, but shifting furniture, strange shrieks and howls could not be so easily dismissed. The strange appearance of moving lights of different colours and the breaking of the ropes that tethered the cattle without signs of cutting were beyond any straightforward explanation. The farmer's son and heir had apparently done his best without success to solve the riddle, but his parents had always stayed rooted to the spot with fear in the farmhouse whilst the son ventured forth.[16]

John Goldie the 'Philosopher' was God fearing, but had no truck with the presence on Earth of the Devil and made it known that he could solve this riddle in a Sherlock Holmes style of logical investigation. Despite his reservations the farmer invited him to the farm, accompanied by his friends, Mr Gillies of Kilmaurs, the 'New Licht' minister; and Robert Muir, a Kilmarnock merchant and Kirk elder. After a number of questions relating to possible enemies and an inspection of the broken ropes he declared that this was the work of man and not the Devil. Swearing the farmer to secrecy he advised him to hide in the byre that night. Once darkness had fallen the farmer, hiding in the byre as instructed, became aware of the usual disturbances and suddenly saw a shadowy figure of a man holding a trumpet-like instrument with which he was making the unnatural sounds that had scared him so. Rushing forward he seized the culprit only to find that it was his own son.[17]

It transpired that the son had some knowledge of chemistry and had made what we would call coloured fireworks. The ropes had been severed with nitric acid, then known as aqua fortis (strong water). Goudie had logically deducted that the son, hoping to scare his father into retirement so that he could run the farm, was the 'Devil on Earth'. The 'philosopher's' reputation was greatly enhanced whilst the son was mortified and humiliated to the extent that he left Ayrshire and was never seen in these parts again.[18]

Association with Robert Burns

[edit]

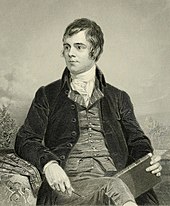

Goldie was 40 years older than Robert Burns;[3] they were on good terms, and Burns wrote the Epistle to John Goldie in 1785 following the publication of a new edition of "Goudie's Bible".

Epistle to John Goldie in Kilmarnock

|

Goldie wrote against the "lying vanities" of those people who interpreted the Bible literally, being called upon as "Terror o'the Whigs":[19] here "Whig" means a Presbyterian of the Auld Licht school, the poet being of the New Licht

Tradition states that Goldie visited Robert Burns in 1785 at Mossgiel Farm while on a business trip to Mauchline during harvest time, the two men sat down behind a stook (sheaf) while the poet recited a few of his compositions. Goldie had first become aware of Burns through the circulation of manuscript copies of Burns' poem and satire "The Twa Herds".[20]

So impressed was Goldie with Burn's poetry that he encouraged him to publish his work[20] and later stood joint surety to the printer John Wilson for the printing of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, as Wilson would not risk publication without payment.[21][19][15] Burns visited Goldie's home where he was introduced to a number of the leading citizens of the town, such as the Town-clerk, William Paterson of Braehead; Robert Muir, a wine merchant; Major Parker of Asslos (banker); Dr William Moore and Thomas Samson, eventually becoming friends with a number of the leading figures in Kilmarnock.[22][19] In the course of the evening Burns recited several of his poems and those present agreed to stand surety for the publication of his poems.[23] Such was their enthusiasm that several of these supporters appear in the subscription list of Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (Edinburgh Edition).

It is recorded, probably from his son, that Goldie said "Robin, I’ll tell you what to do. Come your wa's down to Killie (Kilmarnock)some day next week, and tak' pat-luck wi' me. I ha'e twa or three guid friends that'll be able to set the press a-going."[6] Young, the Kilmarnock Edition researcher, states that in 1785 Goldie was influential in persuading Burns to publish his poems and that from the start it was a group project.[24]

James Mackay accepts that such a meeting may have taken place but without the immediate result of the publication of Burns' poems.[20] However, Burns' literary effusions during 1785-86 were reaching a climax following encouragement to publish from first Richard Brown, then Gilbert Burns, John Goldie and a list of 350 subscribers.[25] Goldie is said to have been a powerful influence in dissuading Robert Burns from his avowed intention of emigrating to Jamaica.[2]

Wilson suggests that the poet originated some of the satirical pieces in the company of these 'leading citizens' and that they were composed in their houses, emphasising that his poems were published with the assistance of these gentlemen.[26]

Burns was a daily visitor to Goldie's house during the time in 1786 that his manuscripts were at the printing works of John Wilson and he corrected the proofs there and wrote many letters, meeting future patrons as subscribers to his first published work, the Kilmarnock volume.[23][10][27] Goldie lived in the second flat of the building occupied by Messrs. Stewart who were ironmongers at the Cross.[27] Next door was the home of Baillie Gregory and Burns also visited their flat on occasions to work on his proofs as well as to listen to Mrs Gregory playing one of the few pianos to be found in the town at that time.[27]

The local historian Archibald Mackay noted that significantly in terms of local contacts, the Kilmarnock Cross premises of John Wilson had belonged to John Goudie, his friend and supporter.[28]

David Sillar and Gavin Turnbull both composed verses on John Goldie, Turnbull writing that :-

Goldie's son, Lieutenant Goldie, R.N., many years later recalled the general persona and demeanour of Burns as he first knew him and went on to recount the great change in appearance and confidence that came over the bard after his time in Edinburgh following the publication of his poems.[6]

It seems that Goldie's writings had a more than subtle effect upon Robert Burns' thoughts and these influences were recorded in several of his poems.[29]

Goldie's significance has perhaps been overlooked because the many manuscripts and letters from Burns, Lord Kames, and other celebrated men of the day were destroyed during his son's (Lieutenant Goldie R.N.) time away at sea.[2]

Micro-history

[edit]

Goudie's Bible was often the subject of ridicule by his enemies and one incident is recorded that when in Ayr. He was entering a bookshop just as a clergyman, with whom he was acquainted, was leaving with a package of books and he asked him in an offhand friendly manner what he had purchased, the response was "Just buying a few ballads to make psalms for your bible."[13]

He took a great interest in the construction of a canal from Kilmarnock to Troon and went so far as to survey a suitable route and indeed in 1796 the Kilmarnock Council considered requesting Parliament for an act to build a canal from Riccarton to Troon.[8]

It is said that he lost money in mining speculations and was cheated by his partner towards the end of his life.[9]

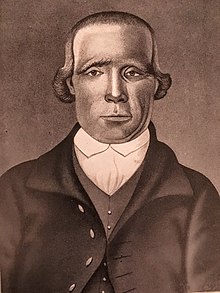

His portrait, supposedly a good likeness, was painted by a Mr. Whitehead with a globe in the background.[2]

See also

[edit]- Haining Place and the Barony of Haining-Ross

- Robert Burns and the Eglinton Estate

- Robert Muir of Loanfoot

- Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect

- Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect (Edinburgh Edition)

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ a b c d Mackay, Page 168

- ^ a b c d e f g Wikisource John Goldie

- ^ a b c McIntyre, page 55

- ^ a b c Dougall, Page 211

- ^ Paterson, Appendix. p.3

- ^ a b c d John Goudie 1717

- ^ Ayrshire. Publication 1910. Revised 1908

- ^ a b c d e f Mckay (1880), Page 191.

- ^ a b The Burns Enclyclopaedia

- ^ a b c d Mckay (1880), Page 189.

- ^ Paterson, Appendix. p.4

- ^ Dougall, Page 210

- ^ a b c Mckay (1880), Page 190.

- ^ Douglas, Page 193

- ^ a b Purdie, page 146

- ^ Blair, page 97

- ^ Blair, page 100

- ^ Blair, page 101

- ^ a b c Boyle, page 40

- ^ a b c Mackay, page 230

- ^ Paterson, Appendix. p.5

- ^ Mckay (1880), page 184

- ^ a b Paterson, Appendix. Page 5

- ^ Young, page xxii

- ^ Mackay, page 231

- ^ Wilson, page 74

- ^ a b c Adamson, p.142

- ^ McKie, James, ed. (1855). The Ayrshire Wreath. 1855. James Mckie. p. 20.

- ^ McGinty, pages 238 - 244

- Sources and bibliography

- Adamson, Archibald (1879). Rambles Through the Land of Burns. Kilmarnock : Dunlop & Drennan.

- Blair, Anna (1983). Tales of Ayrshire. London : Shepeard - Walwyn. ISBN 0-85683-068-2.

- Boyle, A. M. (1996). The Ayrshire Book of Burns-Lore. Darvel : Alloway Publishing. ISBN 0-907526-71-3.

- Dougall, Charles S. (1911). The Burns Country. London: A & C Black.

- Mackay, Archibald (1880). The History of Kilmarnock. Kilmarnock : Archibald Mckay.

- Mackay, James (2004). Burns. A Biography of Robert Burns. Darvel : Alloway Publishing. ISBN 0907526-85-3.

- McGinty, J. Walter (1996) "John Goldie and Robert Burns," Studies in Scottish Literature: Vol. 29: Iss. 1

- McIntyre, Ian (2001). Robert Burns. A Life. New York : Welcome Rain Publishers. ISBN 1-56649-205-X.

- Paterson, James (1840) (Editor). The Contemporaries of Burns: and the more recent poets of Ayrshire. Edinburgh : H. Paton.

- Purdie, David; McCue Kirsteen and Carruthers, Gerrard. (2013). Maurice Lindsay's The Burns Encyclopaedia. London : Robert Hale. ISBN 978-0-7090-9194-3.

- Westwood, Peter J. (2008). Who's Who in the World of Robert Burns. Robert Burns World Federation. ISBN 978-1-899316-98-4.

- Wilson, John and Chalmers, Robert (1840). The Land of Burns. Glasgow : Blackie & Son.

- Young, Allan & Scott, Patrick (2017). The Kilmarnock Burns. A Census. University of South Carolina. ISBN 978-1-976245-10-7.