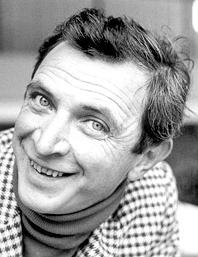

John Cranko

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2023) |

John Cranko | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 15 August 1927 |

| Died | 26 June 1973 (aged 45) On board a transatlantic flight from Philadelphia to Stuttgart |

| Occupation(s) | Ballet dancer and choreographer |

| Parent(s) | Herbert and Grace Cranko |

John Cyril Cranko (15 August 1927 – 26 June 1973) was a South African ballet dancer and choreographer with the Royal Ballet and the Stuttgart Ballet.

Life and career

[edit]Early life

[edit]Cranko was born to Herbert and Grace Cranko in Rustenburg in the former province of Transvaal, Union of South Africa. As a child, he would put on puppet shows as a creative outlet. Cranko received his early ballet training in Cape Town under the leading South African ballet teacher and director, Dulcie Howes, of the University of Cape Town Ballet School. In 1945 he choreographed his first work (using Stravinsky's Suite from L'Histoire du soldat) for the Cape Town Ballet Club.[1]

He moved to London, studying with the Sadler's Wells Ballet School (later called the Royal Ballet) in 1946[2] and dancing his first role with the Sadler's Wells Ballet in November 1947.[3]

London

[edit]Cranko collaborated with the designer John Piper on Sea Change, performed at the Gaiety Theatre, Dublin, in July 1949. They created a season of ballet at the Kenton Theatre, Henley, in 1952 and collaborated again for Sadler's Wells Ballet on The Shadow, which opened on 3 March 1953.[4][5] This period marked a transition in Cranko's career from dancer to full-time choreographer, with his last performance for the Sadler's Wells Ballet taking place in April 1950.[6] At 23 years of age, he was appointed as resident choreographer for Sadler's Wells Theatre Ballet's 1950–51 season.[7]

For the company's Festival of Britain season in 1951 Cranko choreographed Harlequin in April, a "pantomine [sic] with divertissements" to music by Richard Arnell,[8] as well as the comic ballet Pineapple Poll,[4][9] to the music of Arthur Sullivan (newly out of copyright) arranged by the conductor Charles Mackerras.[2] Another collaboration with Mackerras followed in 1954 with The Lady and the Fool, to music by Verdi.[2]

In January 1954, Sadler's Wells Ballet announced that Cranko was collaborating with Benjamin Britten to create a ballet. Cranko devised a draft scenario for a work he originally called The Green Serpent, fusing elements drawn from King Lear, Beauty and the Beast (a story he had choreographed for Sadler's Wells in 1948) and the oriental tale published by Madame d'Aulnoy as Serpentin Vert. Creating a list of dances, simply describing the action and giving a total timing for each, he passed this to Britten and left him to compose what eventually became The Prince of the Pagodas.[10]

Cranko wrote and developed a musical revue Cranks, which opened in London in December 1955, moved to St Martin's Theatre in the West End the following March, and ran for 223 performances. With music by John Addison, its cast of four featured the singers Anthony Newley, Annie Ross, Hugh Bryant and the dancer Gilbert Vernon; it transferred to Broadway at the Bijou Theatre. An original cast CD has been released.[11] Cranko followed the format of Cranks with a new revue New Cranks opening at the Lyric Theatre Hammersmith on 26 April 1960 with music by David Lee and a cast including Gillian Lynne, Carole Shelley and Bernard Cribbins, but it failed to have the same impact.[2]

In 1960, Cranko directed the first production of Benjamin Britten's opera A Midsummer Night's Dream, at the Aldeburgh Festival.[12] When the work had its London premiere the following year at Covent Garden, Cranko was not invited to direct, and Sir John Gielgud was brought in.[13]

Stuttgart

[edit]Prosecuted for homosexual activity[14], Cranko left the UK for Stuttgart, and in 1961 was appointed director of the Stuttgart Ballet,[5] where he assembled a group of talented performers such as Marcia Haydée, Egon Madsen, Richard Cragun, Birgit Keil and Susanne Hanke. Among his following choreographies were Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare in 1962, set to music by Prokofiev, Onegin in 1965, an adaptation of the verse novel Eugene Onegin by Alexander Pushkin, set to music by Tchaikovsky (mainly piano music, including The Seasons and music from lesser-known operas), orchestrated by Kurt-Heinz Stolze, The Taming of the Shrew by Shakespeare in 1969 using keyboard music by Domenico Scarlatti, Brouillards in 1970, Carmen in 1971 (music by Wolfgang Fortner and Wilfried Steinbrenner)' Initials R.B.M.E. (music by Johannes Brahms) in 1972 and Spuren (Traces) (music by Gustav Mahler) in 1973.

Cranko's work was a major contribution to the international success of German ballet beginning with a guest performance at the New York Metropolitan Opera in 1969. At Stuttgart, Cranko invited Kenneth MacMillan to work with the company, for whom MacMillan created four ballets in Cranko's lifetime and a fifth, Requiem, as a tribute after Cranko's death.[15] At Cranko's instigation the company established its own ballet school in 1971; it was renamed the John Cranko Schule in his honour in 1974.[16] His assistant and choreologist Georgette Tsinguirides preserved his works in Benesh Movement Notation.

Death and legacy

[edit]In 1973, Cranko choked to death after suffering an allergic reaction to a sleeping pill he took during a transatlantic charter flight from Philadelphia to Stuttgart, two days after the company completed a successful tour of the United States at the Academy of Music in Philadelphia. The flight made an emergency landing in Dublin where Cranko was pronounced dead upon arrival at a hospital.[17] His mother, Grace, who was divorced from Herbert and lived in what was then Rhodesia, learned of his death from a radio broadcast.[citation needed]

Cranko was buried at a small cemetery near Castle Solitude in Stuttgart.[18]

In 2007, the Stuttgart Ballet celebrated what would have been Cranko's 80th birthday with the Cranko Festival.[19] The ballet Voluntaries by Glen Tetley was created in his memory. The John Cranko Society in Stuttgart, founded in 1975, promotes knowledge of ballet and Cranko's work, supports performances and talented dancers, and every year presents the John Cranko Award.[20]

References

[edit]- ^ "John Cranko", Stuttgart Ballet. Retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ a b c d Dromgoole, Nicholas. "John Cranko", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, retrieved 19 March 2015, (subscription or UK public library membership required)

- ^ "John Cranko" Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Royal Opera House Performance Database, retrieved 19 March 2015

- ^ a b Piper, Myfanwy (1954). "Portrait of a Choreographer". Tempo (32): 14–23. doi:10.1017/S0040298200051871. JSTOR 943196. S2CID 143708560.

- ^ a b Reed, Cooke & Mitchell, p. 94

- ^ "John Cranko" Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Royal Opera House Performance Database, retrieved 19 March 2015

- ^ "John Cranko", Programme booklet for Onegin, Royal Opera House, Covent Garden 2014–2015 season, p. 31

- ^ Royal Opera House Collections Online

- ^ "John Cranko – Pineapple Poll – YouTube". YouTube. 11 October 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

- ^ Reed, Cooke & Mitchell, pp. 258–260.

- ^ "Cranks". The Guide to Musical Theatre. 2014. Retrieved 26 June 2014.

- ^ "A New Midsummer Night's Dream", The Times, 11 June 1960, p. 11.

- ^ "London Triumph for Britten's Dream", The Times, 3 February 1961, p. 13

- ^ https://www.gramilano.com/2023/01/biography-john-cranko/

- ^ Parry, pp. 711–716.

- ^ "History" Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine John Cranko Schule, retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "John Cranko Dies at 45; Stuttgart Ballet Director". The New York Times. 27 June 1973.

- ^ File:John Cranko Grabstein.jpg

- ^ "Das Stuttgarter Ballettwunder" Archived 2 April 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Arte, retrieved 19 March 2015.

- ^ "Aktuelles", John-Cranko-Gesellschaft, retrieved 19 March 2015.

Sources

[edit]- Killar, Ashley (2023). Cranko: The Man and his Choreography (2nd ed.). Troubador. ISBN 978-1-80514-171-6.

- Parry, Jann (2009). Different Drummer: The Life of Kenneth MacMillan. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-24302-0.

- Percival, John (1983). Theatre in My Blood: A Biography of John Cranko. London: Herbert Press. ISBN 978-0-90696-904-5.

- Reed, Philip; Cooke, Mervyn (2008). Mitchell, Donald (ed.). Letters from a Life: The Selected Letters of Benjamin Britten, Vol. 4 1952–1957. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. ISBN 978-1-84383-382-6.

External links

[edit]- John Cranko website (in German)

- 1927 births

- 1973 deaths

- Choreographers of The Royal Ballet

- Dancers of The Royal Ballet

- Drug-related deaths in the Republic of Ireland

- Gay dancers

- South African gay men

- People associated with Gilbert and Sullivan

- People prosecuted under anti-homosexuality laws

- People convicted for homosexuality in the United Kingdom

- People from Rustenburg

- South African expatriates in England

- South African people of Jewish descent

- University of Cape Town alumni

- Victims of aviation accidents or incidents in international waters

- 20th-century ballet dancers

- Stuttgart Ballet

- 20th-century South African LGBTQ people